Title of Work and its Form: “Indecision,” pop song

Author: Stephen Duffy and Steven Page (On Twitter: @stevenpage)

Date of Work: 2010

Where the Work Can Be Found: The song is included on Mr. Page’s album Page One. You may also view the song’s official video below.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Poetic Meter

Discussion:

The narrator of “Indecision” is singing to a lover (or prospective lover). The narrator could easily be a woman, but I will use the male pronoun for simplicity’s sake. He knows that he is indecisive—hence the title—and understands the negative emotional impact he has on the person he loves. His inability to make a firm choice could, at some point, lead him to leave. On the other hand, his inability to commit also prevents him from leaving. The lyrics are set to a good old-fashioned upbeat rock tune; the narrator is trying to put a favorable spin on the situation that he knows is hurting the person he loves. I can certainly relate; you put on a bright smile as you tell a sad story so as not to push people away. The music contains about a zillion hooks and the chorus is straight-on rock. The verses keep your attention by employing a jazzy, Latin, syncopated feel.

Mr. Page is right up there as one of the singers/songwriters who meant a ton to me during my formative years. Mr. Page, of course, was the co-lead singer of Barenaked Ladies and wrote a bunch of all-time classic songs during his time in the band. I love the material he produced with Ed Robertson (another stellar songwriter) and I always felt they had a fascinating dynamic. Lennon and McCartney had different artistic ideas and outlooks on the world that combined to make great music even greater. Mr. Page and Mr. Robertson are both awesome, just in different and complementary ways.

You’ll note, however, that this song was written with Stephen Duffy of The Lilac Time. Mr. Duffy joined Mr. Page to write some of my favorite Barenaked Ladies songs. Can you believe this set list: “Jane,” “Everything Old is New Again,” “The Wrong Man Was Convicted,” “Alternative Girlfriend,” “I Live With it Everyday” and “Call and Answer”? (And I can’t help but mention The Vanity Project, a whole album that Mr. Page wrote with Mr. Duffy.)

Look at the lyrics in the first verse:

I’ve always been a creature of habit

Put another way, I’m addicted to you

I’m predisposed to habit

Happiest when I don’t know what to do

If you read them like poetry (which they are, of course), you’ll notice that Mr. Page plays with the meter of the lines. To read the poem aloud properly, you might have to mark it up a little to find the way the words should sound. This is a good thing! Mr. Page keeps the verses interesting by keeping you on your toes. When you write an Elizabethan sonnet, you’re somewhat restricted with respect to meter because you must stick to iambic pentameter. Mr. Page sings to a Latin beat that keeps you wondering how he’s going to fit in all of the words and the lines’ end rhymes.

Pretend you don’t understand English. What would you know about “Indecision” if you happened to hear it? You would think that it was a fun toe-tapper. As Mr. Page does so often, he gives the song a dark side that adds complexity. There’s certainly nothing wrong with writing a perfectly happy straight-forward rocker or poem or short story. (Hmm…I’m thinking Warrant’s “Cherry Pie.” There isn’t a great deal of depth to that song.) Mr. Page’s work sticks with you because there is always more emotion beneath the surface. Listening to “Indecision” leads to a number of questions:

Will the narrator ever get his act together?

Will the lover tire of him and leave?

If he’s so smart, why can’t he help himself?

How did his parents affect his current mental state?

Listening to “Cherry Pie” leads to only one question:

My goodness…can you imagine what it was like to be a member of Warrant in the 1980s?

What Should We Steal?

- Syncopate your lines, just as a songwriter syncopates his or her music. When the audience can’t predict where the beat of your sentences will go, they will be more likely to lean forward and listen/read more closely.

- Bury some pathos underneath the surface of your work. Humans are not simple and neither are their emotions. Be sure to explore all of the facets of your characters and their situations.

Bonus: You really have to see this amazing vocal performance. Mr. Page sings the Leonard Cohen song “Hallelujah” at the funeral service for Canadian politician Jack Layton. Absolutely haunting:

Song

2010, Poetic Meter, Stephen Page, The Beatles

Title of Work and its Form: “Section 8,” short story

Author: Jaquira Diaz (On Twitter: @jaquiradiaz)

Date of Work: 2011

Where the Work Can Be Found: The short short story first appeared in the Winter 2011 issue of The Southern Review, a highly prestigious journal that is also a lot of fun. “Section 8” was subsequently nominated for an won a Pushcart; the story can be found in the 2013 Pushcart anthology.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Narrative Restraint

Discussion:

Nena is a young woman who has some problems. She was sent to juvie for stealing beer and doesn’t exactly have the most attentive parents. Nena is also coming to grips with her sexuality; she has feelings she doesn’t quite understand for her “homegirl” Boogie. Nena is also concerned about a strangler who has been targeting “professional, openly gay men.” (Folks who don’t understand the importance of proper grammar should take note of the extreme importance of that comma!) Unfortunately, others at Nena’s school believe that Boogie is a lesbian and take the time to spraypaint epithets on her locker. Nena does nothing. In the climax of the story, young men spray Boogie with bleach. This time, Nena confronts them and the assault ends. The relationship between Nena and Boogie is irrevocably changed.

Ms. Diaz puts a lot of balls in the air. There’s a killer on the loose, a young woman is learning about her sexuality, there is crazy bullying in her school…all kinds of great story threads are tied together in the story. As a guy who is pretty focused on the structure of stories, I would ordinarily want to talk about what a writer can steal from the way Ms. Diaz organized her story. (Each section of the story contributes to the overall narrative, but Ms. Diaz does deal with the dramatic present in an interesting way.)

Instead, I think Ms. Diaz gives us a lot to steal in terms of narrative restraint. Nena is an outspoken character who doesn’t allow others to push her around. In narrating her story, however, Nena holds a lot back while still providing the reader with the clues we need to read between the lines. Halfway through the story, after describing a sweet scene she shared with Boogie, Nena offers a flashback:

The first time had been in juvie. It was Ethel, a girl from an Opa-locka crew.

Nena is confused about her desires and possibly ashamed and scared of what they mean about her. Ms. Diaz allows Nena to make her confession (she committed lesbian acts) without making that confession complete. Yes, this kind of tactic puts a lot of distance between reader and narrative. Sometimes, that can be a bummer. In this case, however, it feels perfectly appropriate when you consider the character and her psychology and social situation. Nena never explicitly describes why the Strangler means so much to her, allowing the reader to come to his or her own conclusion.

And look at how Ms. Diaz has Nena handle the climax of the story. When the jerks are painting slurs on Boogie’s locker, Nena thinks:

I thought I should hug her, say, “Fuck those assholes. They don’t even know you.”

But I didn’t. I didn’t say one word. Just turned and walked away.

Nena is clearly having complicated thoughts about the incident, but we are not allowed access to them. The information we DO get is enough for us to understand how the event makes Nena feel.

And look at the calm narration during the climactic fight:

I lunged at him. Pushed him back as hard and fast as my body would let me. He took a few steps, tried to steady himself, fell on his ass. The crowd backed off, but Nestor turned his water gun at me and sprayed. I didn’t care. I went directly for him.

Even though the narrator primarily gives us sparse reportage, Ms. Hill has built the emotional stakes enough that we can cheer for Nena as she stands up for Boogie (and for herself.) There are times during which your narrator should editorialize and should make explicit confessions, but the end of “Section 8” is more powerful because of Ms. Diaz’s restraint.

The ending of the story is also extremely important. After Nena relates a little bit of what happens in the future, she returns to the dramatic present to tell what happened after the jerks took off with their bleach guns:

She grabbed hold of my shoulders, her eyes narrow. “Don’t you fucking touch me,” she said, before pushing me back against the bus stop.

That night, right outside of the Section 8 projects, someone set another woman on fire.

Wow…am I right? The last sentence is a gut punch. Some might say that it’s extraneous because it doesn’t directly relate to the characters or the moment. On the other hand, the last sentence brings the story to a new level, connecting the violence committed against Nena and Boogie to the Strangler and beyond.

What Should We Steal?

- Calculate the proper distance between narrator and reader. Most teenagers are guarded about their inner truths; concealing information from your reader is appropriate when your narrator would realistically do so. Establishing a vast narrative distance can also allow you to zoom in for additional effect.

- Punch your reader in the gut by bringing in the world at large. After spending several pages immersed in Nena’s perspective, Ms. Diaz offers us a sentence that doesn’t need to have come from her narrator. The statement is really a rhetorical question that makes a personal story about even larger issues.

Short Story

2011, 2013 Pushcart, Jaquira Diaz, Narrative Restraint, The Southern Review

Title of Work and its Form: “Donkey Greedy, Donkey Gets Punched,” short story

Author: Steve Almond

Date of Work: 2009

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story first appeared in Issue 40 of the excellent journal Tin House and was subsequently chosen by Richard Russo for The Best American Short Stories 2010.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Multimedia

Discussion:

If you’re new to literary pursuits, you may not have experienced the utterly strange kind of pleasure that I derived from this story. I reviewed Issue 40 of Tin House for NewPages and loved Mr. Almond’s story a LOT. Months and months later, I picked up the 2010 Best American and thought the first story seemed pretty familiar… The book begins with that story I loved from Tin House! Did I have anything at all to do with Mr. Almond’s story or the honors it received? Of course not. But I did feel that strange pleasure; I read a story I knew was great and important people subsequently agreed with me. (It’s like when you see a minor league ballplayer you think is great and the guy goes on to a superstar career in the bigs.)

“Donkey Greedy, Donkey Get Punched” is a philosophical fight between Dr. Raymond Oss, a psychoanalyst, and Gary “Card” Sharpe, “enfant terrible of the World Poker Tour.” Dr. Oss doesn’t tell his new patient that he has a somewhat unhealthy level of interest in poker and a bit too much of the love of gambling that rules Sharpe’s life. Sharpe has many problems and doesn’t deal with them in a healthy way; he doesn’t want to change. He loves his life and the excitement he feels from using his intellect and intuition to win money from people. Their doctor/patient relationship ends with some acrimony. In the climactic scene, Dr. Oss has relapsed and is again playing poker at Artichoke Joe’s when Sharpe (a superstar in the minds of the bushers at the table) strolls in and sees the Good Doctor. What happens next? As they said on Reading Rainbow: “read the book!” (Dum dum dum dum!)

There’s so much we can steal from the story. The first thing we should steal was clear to me when I read the story in Tin House, a journal that is particularly attractive and puts a lot of energy into its graphic design. It can be very difficult to describe a card game. Or a baseball game. Or a soccer match. Well, it’s not that hard to describe a soccer match. Here’s my extremely American-sounding description of the most recent World Cup final:

The guy kicked it to another guy who kicked it to another guy, but he fell down so the guy from the other team kicked the ball, but then the ball was kicked out of bounds. So the guy threw it to another guy who kicked it to another guy, but he fell down so the guy from the other team kicked the ball, but then the ball was kicked out of bounds. So the guy threw it to another guy who kicked it to another guy, but he fell down so the guy from the other team kicked the ball, but then the ball was kicked out of bounds. So the guy threw it to another guy who kicked it to another guy, but he fell down so the guy from the other team kicked the ball, but then the ball was kicked out of bounds. So the guy threw it to another guy who kicked it to another guy, but he fell down so the guy from the other team kicked the ball, but then the ball was kicked out of bounds. Time ran out, but the referee added eight more minutes just because. So the guy threw it to another guy who kicked it to another guy, but he fell down so the guy from the other team kicked the ball, but then the ball was kicked out of bounds. So the guy threw it to another guy who kicked it to another guy, but he fell down so the guy from the other team kicked the ball, but then the ball was kicked out of bounds. Then one of the teams celebrated.

Mr. Almond makes it easy to understand the climactic hand of poker that Dr. Oss and Sharpe play at the end of the story. How? He inserted simple graphics into the story, like so:

A written description would likely be less effective. (Especially if I write it.)

A written description would likely be less effective. (Especially if I write it.)

Dr. Oss was dealt the ace of spades and the king of hearts.

There are a number of steps in a hand of hold ‘em…Mr. Almond presents the information in a clear way that just so happens to avoid words.

What else should we steal from Mr. Almond? He populated his story with a protagonist and an antagonist. Dr. Oss wants to help Sharpe to attain mental health and to beat Sharpe in a hand of poker. You better bet that Sharpe tosses down a whole bunch of obstacles to prevent Dr. Oss from achieving those goals.

What Should We Steal?

- Capitalize upon the advantages of visual media when possible. Yes, yes. A picture is worth a thousand words, but you can’t just print out five pictures and staple them together and send them to Tin House. You can, however, make use of the benefits of visual media when possible. Instead of describing a bunch of playing cards, for example, you can include images. There’s an added benefit; folks who play poker will remain in your narrative that much more because they’re seeing the cards in a form to which they’re already accustomed.

- Equip a story with a clear protagonist and a clear antagonist. Your main character should have very clear desires and there should be someone who is always throwing obstacles in the poor guy’s way. Think of a Bond movie. Bond wants to disable a communications satellite and the bad guy wants to keep using the satellite…and to kill Bond, of course.

Short Story

Best American 2010, Multimedia, Steve Almond, Tin House

Title of Work and its Form: “Getting a Get,” creative nonfiction

Author: Marcela Sulak

Date of Work: 2012

Where the Work Can Be Found: Ms. Sulak’s piece was published in the Winter 2012/2013 issue of The Iowa Review. (A top journal that is also beautifully designed.)

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Writing Identity

Discussion:

Ms. Sulak begins by describing her fairy-tale romance: “We dated for three weeks, were engaged for four, and lived together for six.” At the end of the first paragraph, she informs the reader that the fairy tale didn’t last: “Divorce,” she says, “gives us more, if less romantic narrative options.” The piece describes the process by which she and her husband finalized their divorce in a rabbinical court. As the wife in the case, Ms. Sulak is largely a spectator. The rabbis deliberate, deciding whether or not the differences between Ms. Sulak and her husband were irreconcilable enough to grant the divorce. In between sections taking place in the dramatic present (the divorce), Ms. Sulak tells the reader about her wedding and and employs the recurring motif of the fairy tale to illuminate the difference between reality and the way we imagine our lives will end up. Ms. Sulak is dealing with some very heavy concepts: feminism, the state of women in Orthodox Judaism, the meaning of grace in our lives, the pain of separating from someone you love and more. In the end, Ms. Sulak fulfills the promise made by her title and gets her Get, wondering where the document, like the intimacy she shared with her husband, really ends up.

Humans are storytelling creatures: much more homo narans than homo sapiens. We aren’t made of one narrative, but countless ones that intertwine to make us who we are. How often have you noticed the connection between two different situations from different formative experiences in your life? These anecdotes are part of the larger story of who you are. Yes, friends, we are creatures made from stardust and story and poetry and music and art. Ms. Sulak makes this connection explicit by weaving descriptions of fairy tales into her narrative. Ms. Sulak translates these stories and they are clearly an important part of who she is. Early in the piece, she confesses that she tried to alleviate some of the stress of the hearing by reading poems; the tears she cried leads her to think about the dubious relationship between birds and women in fairy tales.

With such a passive role in her divorce ceremony, it’s not surprising that Ms. Sulak contemplated the free will granted by the deity in which she believes. “If G-d would not withdraw,” she writes, citing mystical Jewish literature. “People would lack free will.” Ms. Sulak then includes a poem she had previously published on the topic of grace and how a person shapes his or her identity in the context of the forces that control us. Every writer unites his or her work in a different way and some more obviously than others. Think about Stephen King; most of his works take place in the same universe and in some of the same communities. Castle Rock and Derry…they’re all clearly a part of Mr. King’s concept of himself.

“Getting a Get” is primarily a story about how Ms. Sulak GOT her GET. She is, however, an amalgam of all of her experiences. That’s why she stopped her divorce narrative to tell us about her wedding and to relate her daughter’s request for a sibling. Some readers may wonder why Ms. Sulak kept interrupting the dramatic present. By doing so, the author makes the story about a human being in full, not simply a person who happens to be at her divorce hearing.

What Should We Steal?

- Acknowledge that your writing is an important part of your identity. As a writer, you understand a little bit more deeply how strongly who you are is shaped by the stories that happen to you and everyone you meet. Ms. Sulak understood this and inserted one of her poems into the essay; how will you enmesh the works you create?

- Contextualize your primary story by tying it into other important personal events. The “sacraments” may be a list of milestones that help us measure our lives (and those of our characters), but there is so much more to why we are who we are.

Creative Nonfiction

2012, Marcela Sulak, The Iowa Review, Writing Identity

Title of Work and its Form: “” ‘There’s just one little thing: a ring. I don’t mean on the phone.’ “—Eartha Kitt,” poem

Author: Kathy Fagan

Date of Work: 2006

Where the Work Can Be Found: The poem was originally published by the prestigious online magazine Slate. By all means, go check it out right now.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Structure

Discussion:

Kathy Fagan’s “’There’s just one little thing…’” is a poem whose title connects its narrator with that of the song “Santa Baby.” (Ms. Fagan certainly announces that she has taste in her choice of referencing the Eartha Kitt version.) The poem’s narrator clearly announces her (or his…who knows?) desire to receive a diamond ring and to take her rightful place on a pedestal in the relationship. The narrative is complicated in the last two lines:

So snare it,

Santa, from that other

sorry cow.

The Baby Jesus phoned,

says I should wear it now.

It seems as though the narrator has a romantic rival, the “sorry cow.” The reader is left wondering how the conflict will eventually be resolved.

The first thing that jumped out at me was the interesting structure of the poem. Ms. Fagan prepared me to think about popular song, so I couldn’t help but think of the work in that way. The poem begins with a kind of recitative, preparing the reader for the primary “melody” in the verse. The “bridge” arrives as the meter changes completely with the lines “Been bottom./ Done shouldered.” Verse 2 arrives with the 1-2-3 repetition of the lines beginning with “O” and those last two lines serve as a kind of button on the “song.”

It may seem crazy to split up a serious poem in this manner, but Ms. Fagan clearly had some kind of structure in mind. Look at the changes in meter that Ms. Fagan employs:

| Section |

Beginning/Ending Lines |

Dominant poetic feet |

| “Recitative” |

“In lieu…list forthwith” |

Anapests – Iambs – Anapests |

| “Verse 1” |

“Do not buy…buckle under” |

Dactyls |

| “Bridge” |

“Been bottom…my skin” |

Dactyls/Trochees |

| “Verse 2” |

“O halogen…all this time” |

Iambs – Primus Paeon/Trochee - Iambs |

| “Button” |

“So snare…wear it now” |

Iambs |

By mixing it up, Ms. Fagan keeps her audience engaged and prevents readers from being lulled into complacent scanning of the lines. It’s also a lot of fun to transfer between meters, isn’t it? Playing with words and how they fit together isn’t just for kids, right? Adults also enjoy the twists and turns they can find in sentences. Switching between meters also allows Ms. Fagan to place emphasis on certain ideas. There are points in the poem in which the changes stop the reader momentarily. It seems particularly apparent that Ms. Fagan intends “Been bottom./ Done shouldered.” to represent something significant about the character of her narrator.

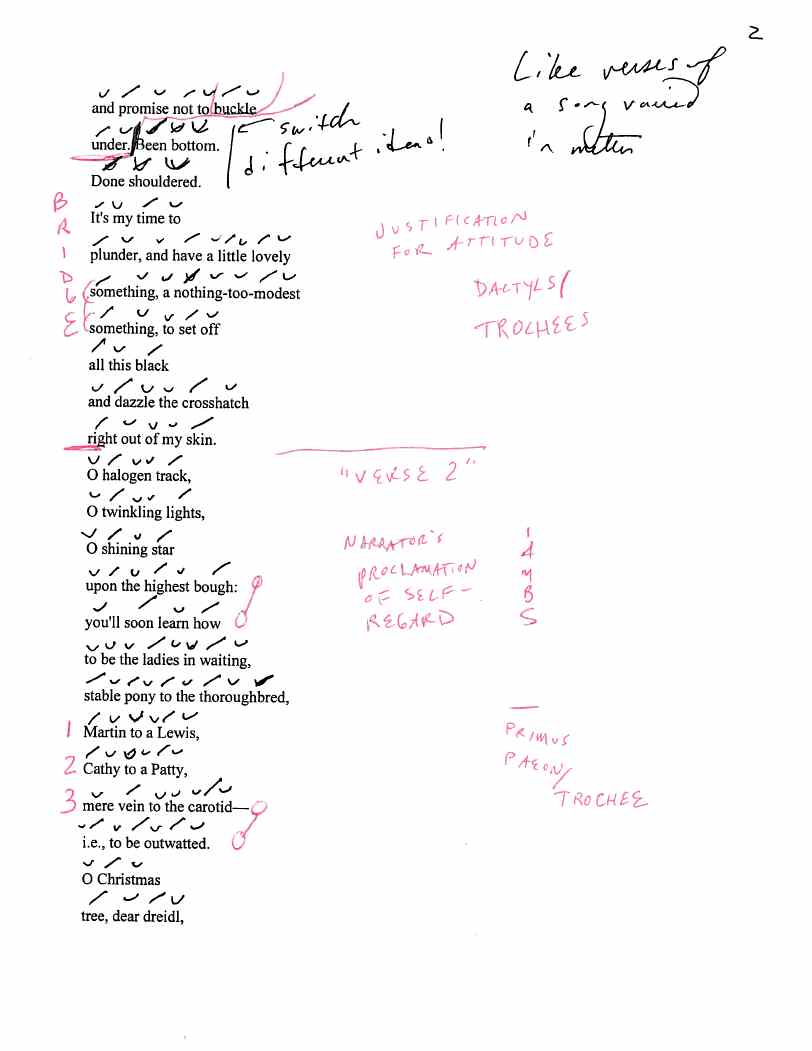

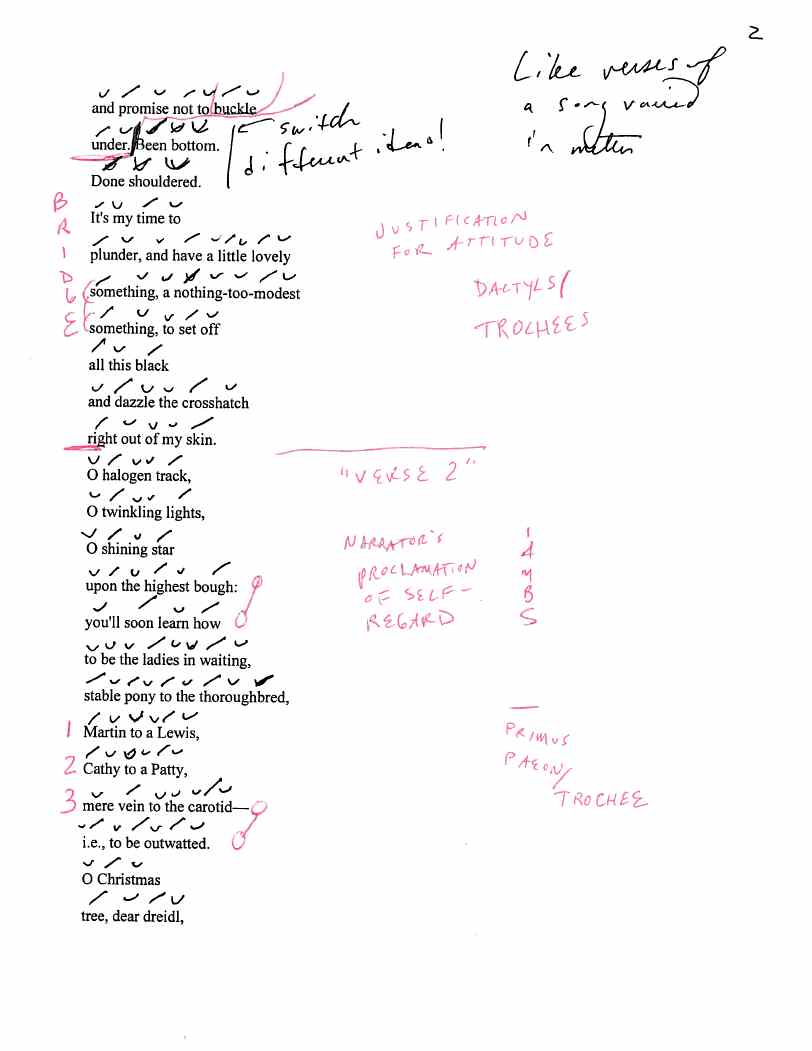

Poetry, of course, is best communicated by the human voice. (If you’ll notice, the link to Ms. Fagan’s poem allows you to hear her reading her work!) When you’re considering the written word on the page, it’s up to you to try and decode the unique kind of music the poet intends to make. Break out your favorite kind of pen and annotate the poem. Jot down the ideas that come to mind! Circle the rhymes you may find! Count the repetitions hidden in the lines! One of the reasons that workshops help so many writers is that everyone in the room is sharing ideas about the work. Some are great, some are just okay, but this analytical process allows everyone to understand the work on a deeper level. When you mark up a page, you’re entering into a discussion with the poet. I hadn’t come up with my overall idea about this poem’s structure until I made my chickenscratches. What might it look like if you mark up a piece of writing? Here’s what I did to a section of Ms. Fagan’s poem:

There’s no right or wrong; I simply wrote what I thought about the piece, which led to even bigger concepts. You’ll also notice that I tried to scan each syllable in the poem, deciding which should be stressed or unstressed. When I compared my thoughts to the way Ms. Fagan made them sound in her reading, I noticed a few differences that illuminated my understanding of the poem. (Her metrical ideas were better, of course.)

There’s no right or wrong; I simply wrote what I thought about the piece, which led to even bigger concepts. You’ll also notice that I tried to scan each syllable in the poem, deciding which should be stressed or unstressed. When I compared my thoughts to the way Ms. Fagan made them sound in her reading, I noticed a few differences that illuminated my understanding of the poem. (Her metrical ideas were better, of course.)

What Should We Steal?

- Place emphasis on important ideas by changing the meter and flow of your sentences. It’s very easy for your reader to be carried away in the wave of words and ideas that you are communicating through your use of beautiful and florid language that tickles their frontal lobe and creates fireworks in their medulla and reinforces why they enjoy reading in the first place. So switch it up sometimes! Use different kinds of sentences for different effects!

- Deface everything that you read to gain a greater understanding of the author’s thoughts and intentions. It’s not always possible to discuss everything you read with other smart people. When you read with a pen in hand, you become your own reading group. (If you’re reading a library book, you should write in pencil.)

Poem

2006, Kathy Fagan, Narrative Structure, Ohio State, Slate

Title of Work and its Form: May We Shed These Human Bodies, short story collection

Author: Amber Sparks (on Twitter at @ambernoelle)

Date of Work: 2012

Where the Work Can Be Found: The book was released by Curbside Splendor, an independent press out of Chicago. Why not purchase the book directly from those fine folks?

Bonuses: Some of the stories in the collection were originally published online. If you haven’t read the book, why not get a small taste of Ms. Sparks’ work? Here’s “Gone and Gone Already,” courtesy of The Splinter Generation. This is “The Chemistry of Objects,” first published by Necessary Fiction. Cool! Here is a podcast on which Ms. Sparks was a guest. And here‘s an old-fashioned printed-word interview with the author.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Experimentation

Discussion:

May We Shed These Human Bodies is a modern short story collection with a classic twist. Most of the stories are quite short and each is unique in its form and tone. The collection can best be compared to other “assembled” books of tales whose aim is to contextualize the human existence and facilitate a deeper understanding of our place in this crazy universe. The stories that comprise May We Shed… are set in places as diverse as realistic corners of the known world and the Afterwards, where all of humanity was taken when they tired of the Earth. Ms. Sparks employs a wide range of narrators, experimenting with first-, second- and third-person points of view. Even more interestingly, Ms. Sparks tells stories in a number of different forms, including a list of historical artifacts, a lesson plan and a response to a self-imposed challenge to write a memoir that “burns clean and true.” Throughout the book, Ms. Sparks finds innumerable ways to create musical sentences while challenging the reader’s intellect as well as his or her heart.

If you couldn’t tell from my summary, it’s not easy to describe the combined effect of the stories in May We Shed… The book is delightfully different from others in the genre. When you pluck a T.C. Boyle collection from the shelf-something you should do on a regular basis-you will find perhaps a dozen stories of similar length. The rhetorical effect of a “traditional” short story collection is usually fairly passive. Each of the author’s characters may indeed share a fictional world, but identifying the unifying thread is somewhat open to interpretation. Is this a bad thing? Of course not. Ms. Sparks, however, has produced a work that cleaves much more strongly to the ethos of “assembled” books like the Arabian Nights and religious books such as the Torah and the Bible or political tomes like the collected writings of Thomas Paine. In a way, each of the pieces in the books stand on their own and have their own clear intention. When read as a whole, the books become something more than the sum of their parts. It is pleasing enough to read about Aladdin and his lamp. Doesn’t the story take on added depth when you consider it was told by a woman who was trying to save the lives of the (remaining) women living under the rule of King Shahryar?

In this way, Ms. Sparks is a modern-day Scheherazade. Each of the thirty-plus stories is unique and clearly comes from a different burst of inspiration. Ms. Sparks clearly enjoys playing with language and takes joy in reconsidering what a story can be. The frame narrative is not as concrete as that of the Arabian Nights, but I felt that the book’s opening story served as a kind of frame. “Death and the People” announces itself bravely:

When Death came and started it all, the people on Earth had already drawn close together to wait for spring.

In short order, all humans are willingly in the Afterwards, a final destination that instead seems like a variation on Limbo. Ms. Sparks adopts the diction of a fairy tale or a religious tome, establishing a great deal of narrative distance. These choices allow Ms. Sparks to write beautiful, poetic lines that invite the reader to fall under the spell of her narrator:

After a while, though, it seemed like everything started to grow and adapt, including the animals and plants. Highways cracked, naked without their blanket of traffic, but soon they were modestly draped in green as moss and weeds, and flowers pushed up through the gaps in the concrete. The skyscrapers bucked and bent, while the trees shoved their branches through the glass panes. After a few centuries, everything the people had made was buried or gone. Everything except the structures of stone that were put up long before the memories of the people had even begun.

Doesn’t this remind you of the writing of someone like Kevin Brockmeier? We should all fit our diction to the special purpose of each work we create.

Short stories can take any form. Whether or not we realize it, every document we create is really a kind of story. For instance, go to The Smoking Gun and look at the documents they’ve collected. Each tells a story in subtext. Look at the Foo Fighters’ concert rider. In this document, the band lists what they need onstage and backstage. The express intent of the document is to make sure that Dave Grohl and his friends have tasty food and their favorite drinks. If you think about it a little, you realize that you’re reading the story of men who have played countless gigs in countless towns and have had countless problems with promoters. Mr. Grohl and his bandmates are doing their best, in a pleasant manner, to convince the promoters to help them put on a great show.

Ms. Sparks appropriates the form of what I can best describe as a writing prompt. “The Effect of All This Light Upon You” begins with a three-paragraph prompt:

Lay your life out flat before us […] Use scissors to slice off the right scenes; no need to reveal everything. Edit brutally. Soak the naked film in dye and roll it over the drum to dry out.

Yes, this is great writing advice all on its own. But Ms. Sparks answers the prompt with seven numbered paragraphs, each of which depicts a different scene from a life. Read together, the piece is a lyric autobiography of the narrator.

What Should We Steal?

- Assume the role of a current-day Scheherazade. I hope that you’re not telling stories in order to save your life, as the original Scheherazade was forced to do. But shouldn’t you feel that same delightful pressure and the same ambition that led her to tell a new, unique and exciting story each night? Write the kind of story you’ve never written before; try a form that is completely alien to you. Imagine the King over your shoulder at the end of the night, asking you what thrills you’ve contrived today.

- Establish the rules of your “world” quickly. Ms. Sparks opened her collection with a story that is reminiscent of a parable and informs the reader that anything can happen in the book. When you manage the expectations of your readers, you can get away with anything.

- Borrow the forms that surround you every day. Write a short story in the form of a civil rights complaint. Write a poem in the form of a credit card application completed by a very rich person…or a very poor one. Ooh…what magic could you work with a story in the shape of a college application essay? Or a clemency plea normally sent to a governor?

Short Story Collection

1001 Nights, 2012, Amber Sparks, Curbside Splendor, Experimentation

Title of Work and its Form: “Best New Horror,” short story

Author: Joe Hill, on Twitter at @joe_hill

Date of Work: 2005

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story was first published in Issue 3 of Postscripts, a journal published by the UK’s PS Publishing. Mr. Hill subsequently chose to lead his first short story collection 20th Century Ghosts with the piece.

Bonuses: Here’s what Terrence Rafferty of the New York Times Sunday Book Review thought of Mr. Hill’s work. (Long story short: he liked it.) And here’s Graham Sleight’s thoughtful review of the collection and its lead story.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Acceptance of Genre Work

Discussion:

Eddie Carroll is the editor of Best New Horror, a yearly anthology of stories that represent the best in the genre. Eddie is in something of a lull in his life—his wife is gone and he hasn’t been really excited about any new stories—when he is sent a copy of “Buttonboy.” It’s a nasty little story about a random act of extreme violence that determines (and becomes) a woman’s fate. The story is controversial and unpleasant and the ending is fairly predictable, but Eddie wants to publish it. The author, Peter Kilrue, is a difficult man to find. Eventually, Eddie does find him. The ending of “Best New Horror” is controversial and fairly predictable. (What can I say? I liked it.) I need to ruin the ending in order to discuss the points I had in mind, so here be spoilers: Eddie tracks Peter down in the middle of nowhere; Peter Kilrue’s mailbox decals have flaked away and they now read “KIL U.” And that may be what happens to Eddie, who heads into Creepy House and quickly realizes that Kilrue is the kind of artist who WRITES WHAT HE KNOWS. The creaky house is filled with weird people who like to chop what looks like liver when shirtless and who like to tie old women to beds with wire. Eddie runs to his car, careful not to twist an ankle: “He had seen it happen in a hundred horror movies.” Eddie remembers that his keys were in the jacket he gave to one of the Creepies. The reader leaves him as Eddie is running away. If anyone can elude homicidal maniacs, shouldn’t it be the guy who spends all of his time reading about them?

Mr. Hill is known primarily as a horror writer, but he seemingly refuses to be stifled by any artificial constraints. Some people, after all, say “science fiction writer” or “romance writer” with a disappointed snarl. Why must a genre classification be perceived as an indication of quality? “The Lottery” and “The Yellow Wallpaper” are rockin’ stories…and they could be considered psychological horror. “The Cold Equations” and Fahrenheit 451 are punch-to-the-gut narratives…even though they’re science fiction. A third of the way through “Best New Horror,” Eddie Carroll editorializes about this sad perception of genre:

Among the cognoscenti, though, a surprise ending (no matter how well executed) was the mark of childish, commercial fiction and bad TV. The readers of The True North Review were, he imagined, middle-aged academics, people who taught Grendel and Ezra Pound and who dreamed heartbreaking dreams about someday selling a poem to The New Yorker.

The conventions of craft are simply tools. Even if you are writing a “literary” story, you would do well to borrow the tools of “horror” writers. (Can you name any writers who are better at ratcheting up the tension in a narrative?) Science fiction is a genre about examining new ideas and new technologies and deciding how they fit into ever-changing concepts of humanity. Writers of “literary” fiction should definitely understand how folks like Ray Bradbury and Harlan Ellison view the world and the people on it. I must confess that I have spent a lot of time thinking about this enforced dilemma. Science fiction was my first love growing up and it has always bothered me when folks dismissed a book or a writer because they worked in a genre of some kind. Stephen King is a top-flight writer, as capable with literary fiction as white-knuckle horror. I read Diff’rent Seasons and The Bachman Books when I was really young and grew up protesting those who said Mr. King was only a vampires-and-women-with-telekinetic-powers kind of guy. (A lot of my students don’t realize that Stand By Me, The Shawshank Redemption and It emerged from the same fertile mind.) I’ll put the aforementioned Harlan Ellison and Ray Bradbury up against any poet with respect to their ability to create beautiful sentences.

Here’s a little chart that elucidates what different genres can teach us about writing craft:

|

Genre

|

What Writers in the Genre Can Teach Us

|

| Action/Adventure |

The creation of compelling protagonists, descriptions of interesting action setpieces |

| Crime |

Simple but extremely descriptive language, an understanding of the fringes of the “real world” |

| Fantasy |

The depiction of elaborate worlds that are realistic and unrealistic at the same time |

| Horror |

How characters feel and act when they are in the greatest physical danger of their lives |

| Mystery/Detective |

The exploration of deviant psychology, the ramifications of violations of the social order |

| Romance |

What brings lovers together and what separates them |

| Science Fiction |

How humanity adapts and changes to ever-changing technology (or how it remains the same) |

| Western |

What it is like to occupy virgin territory, how to write characters who are alone quite a bit |

“Best New Horror” also brings to mind two non-horror works: the Stephen King novella “The Body” and John Irving’s novel The World According to Garp. Two points if you can guess what these three pieces have in common. All three contain framed narrative. In “Best New Horror,” Mr. Hill extensively summarizes “Buttonboy.” Mr. King allows Gordie Lachance to tell the story of Lard Ass. Mr. Irving’s book includes “The Pension Grillparzer,” the title character’s first novella. Including such a framed narrative is a risk. I’ll admit that I skipped “Grillparzer” the when I read Garp as a fourteen-year-old. Why? Because Mr. Irving was telling such a great story about such an interesting young man…and then he assigned me to read dozens of pages of a different story in a different font. (No worries; I’ve long seen the error of my ways in that regard.) I didn’t mind Lard Ass story in “The Body” because it fit into the story; what do teenage guys do around a fire but tell dirty or weird stories?

Mr. Hill, no doubt, knew that he HAD to tell the reader a lot of details about “Buttonboy.” The story, after all, reflects upon Kilrue’s psychology and sets the protagonist into action. Mr. Hill doesn’t waste your time; he describes the plot of “Buttonboy” in sentences that are at once short and declarative and chilling. Our framed narratives should serve as an imperative part of our story; they shouldn’t seem like an accessory.

What Should We Steal?

- Wear your genre badges proudly. Successful genre writers are really demonstrating that they have exceptional skills in at least one facet of storytelling. Romance writers, for example, have extreme insight into what people want to believe about love. When last we see Mr. Hill’s narrator, he’s running for his life, buffeted by the knowledge he gleaned from all the stories he read about characters in the same situation. Mr. Hill, it seems, is saying that understanding genre writing can save your life.

- Ensure that your framed narratives work in the context of the bigger story. Go right ahead: show your reader a poem that your character “wrote.” Just make sure that you’re not holding up the procession of your larger narrative.

Short Story

2005, Acceptance of Genre Work, Genre, Joe Hill, Postscripts

Title of Work and its Form: The Shape of Things, play

Author: Neil LaBute (Cool! Here’s a list of Mr. LaBute’s favorite ten films from the Criterion Collection.)

Date of Work: 2001

Where the Work Can Be Found: The play is performed across the world and was published by Faber and Faber. In 2003, Mr. LaBute released a film version of the play that starred the excellent original cast. Here is the trailer:

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Punctuation

Discussion:

Evelyn is a beautiful artist. Adam is a somewhat plain schlub who works as a security guard in a museum. The couple meets as Evelyn is about to…customize some art that Adam is supposed to protect. Why in the world would a hottie like Evelyn want to go out with Adam? (The audience discovers the truth at the end of the film.) Through the course of the play, Evelyn convinces Adam to improve himself: to get a haircut, to lose weight, to dress in stylish clothing. Adam’s friends notice a change in him and wonder about Evelyn’s true motivations, which she reveals in the climax of the play. (I don’t want to ruin it if you haven’t seen it.)

Mr. LaBute’s script is surprisingly sparse. Mr. LaBute tells you enough about the stage for you to understand what is going on, but the script is really a series of conversations. It’s clear that the flow of the dialogue and the naturalness of the characters was of primary importance to the playwright. In real life, people talk over each other and misunderstand each other and interrupt each other all the time. Mr. LaBute wanted that tone to come through in the dialogue he wrote and, eventually, in the performance of his actors. What did he do in the script to accomplish this goal? Let’s take a look at the very first five lines of the play as written by Mr. LaBute:

ADAM

…you stepped over the line. miss? / umm, you stepped over…

EVELYN

i know. / it’s ‘ms.’

ADAM

okay, sorry, ms., but, ahh…

EVELYN

i meant to. / step over…

ADAM

what? / yeah, i figured you did. i mean, the way you did it and all, kinda deliberate like. / you’re not supposed to do that.

I must confess immediately that I usually don’t like it when writers omit quotation marks or refuse to follow capitalization rules. (After all, those conventions become conventions for a reason! They make prose easier to read!) In this instance, I can certainly respect what Mr. LaBute has done by eschewing capitalization. Doesn’t it make the lines seem like snippets of conversation instead of big pronouncements? I can imagine that actors at a table read would automatically imbue their performance with an interesting flow, which certainly seems like the playwright’s goal. I love his other “trick” without hesitation. What do those slashes mean? Mr. LaBute tells his reader in an introductory note:

the / in certain lines denotes an attempt at interruption or overlap by a given character

Those forward slashes serve as a green light to the actors to play around with the delivery of the lines a little. Adam and Evelyn are about to become lovers; shouldn’t there be some kind of awkwardness as they feel each other out? The forward slashes are also an unobtrusive way to get this point across.

Even better, look at all Mr. LaBute did with just those five first lines.

- Evelyn transgresses against societal convention by getting too close to the artwork. What does this tell us about her? Adam is wishy-washy in doing his job and asking her not to deface the art. What does this say about him?

- Evelyn knows she’s breaking the rules. She corrects his pronoun usage.

- Adam isn’t really forming a sentence in that third line.

- Evelyn states very plainly that she is the kind of person who will ignore societal convention if she feels like it.

- Adam is still wishy-washy. He won’t stand up to her, even when she’s about to break the law.

This brief exchange sums up the play as a whole. Even though some “crazy” things happen during the narrative, Mr. LaBute has prepared us for all of them by hitting us with the truth in the first twenty seconds of the play.

What Should We Steal?

- Employ alternate punctuation and ignore the rules of writing if it will serve your work. Reading is a crazy process that goes on between your eyes and your brain (and then between different parts of your brain). Decide if and when you need to manipulate the reader’s understanding of the words, down to the way they appear on the page.

- Allow your characters to announce themselves immediately. First impressions are important, right? Examine the first things your characters say and do to make sure they arrive with a bang.

Play

2001, Neil LaBute, Punctuation, Rachel Weisz

Title of Work and its Form: “The Hawk,” creative nonfiction

Author: Brian Doyle

Date of Work: 2011

Where the Work Can Be Found: The piece was first published in the February 2011 issue of The Sun. (The glossy lit mag, not the supermarket tabloid.) Go ahead; read the piece right here. Subsequently, the piece was awarded a Pushcart Prize and was included in the 2013 Pushcart Prize anthology.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Inspiration

Discussion:

The titular hawk is a man who, as Mr. Doyle states in the story’s first sentence, “took up residence on my town’s football field, sleeping in a small tent in the northwestern corner, near the copse of cedars.” The Hawk was, years earlier, a star on that very field who had some success in college and in the “nether reaches of the professional ranks.” The man tried some business ventures that didn’t succeed and decided to make his home on the very ground where he first tasted glory. The second half of the piece is Mr. Doyle’s recollection of what The Hawk said to a newspaper reporter who was writing a story about the broken social contract and wanted to use football as a hook. The Hawk’s statements are appropriately poetic, including one very long, very beautiful sentence about the beauty that still exists in the hearts of all mankind.

If you checked the story out, you notice at first that it’s not very long. This is not a problem; Mr. Doyle set out to give voice to The Hawk, and he did so. Make no mistake; whenever we write creative nonfiction, we’re stealing someone else’s life in some way. Even in a memoir, we are appropriating the lives of others; our friends, our parents and anyone else we may include in the narrative? What are the responsibilities we have to those people? Well, that’s up for debate. The reporter wanted to USE The Hawk to reinforce her point about the way society lets others down. To her, The Hawk was a character to be pitied, a man who illustrates the mistakes made by our leaders and by individuals themselves. This is a valid way to go, but Mr. Doyle USED The Hawk to greater effect. The beginning of the essay is contrived somewhat to evoke pathos. How could it not? The guy lives on the football field! He’s living in the past. Mr. Doyle makes a great turn, however, granting agency to The Hawk and allowing the man to tell his own story. You know what? The Hawk is a pretty deep guy and I’m glad to have met him instead of simply being told what he represents.

And how did Mr. Doyle reconstruct the “quietly amazing things” that The Hawk said? Well, I don’t know Mr. Doyle, although I’m sure he’s a great guy. Perhaps Mr. Doyle listened in wonder and then typed out what he remembered when next he was at his desk. On the other hand, I suspect Mr. Doyle may be the kind of writer who brings a notebook with him as much as possible. I learned this lesson early. One day, while waiting for a Greyhound to visit an ex-girlfriend, I overheard the discussion between a man and woman who were clearly very distressed. “Will we be forgiven for what we did?” They wondered. “Don’t you think everyone else will find out our shame?” They asked. Boy, do I wish I had had a notebook with me so I could jot down every creepy/awesome line they were trying to write for me.

What Should We Steal?

- Grant agency to your characters, no matter your genre. Don’t you deserve to determine the course of our own lives and how we are perceived? Your characters deserve no less. If you’re writing nonfiction, consider whether or not you have allowed your characters full citizenship in the work.

- Bring a notebook with you at all times. You never know when a great line is going to pop into your head or when you’re going to be stuck in a twenty-minute line at the grocery store in need of something to do. Even better, you never know when something crazy is going to happen around you that demands to be recorded.

Creative Nonfiction

2011, 2013 Pushcart, Brian Doyle, Inspiration, The Sun

Title of Work and its Form: “Occupational Hazard,” short story

Author: Angela Pneuman

Date of Work: 2011

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story made its premiere in the Spring 2011 issue of Ploughshares as the winner of the Alice Hoffman Prize for Fiction. (Ploughshares, by the way, is one of the best journals out there.) The story was subsequently chosen for the 2012 edition of Best American Short Stories.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Material

Discussion:

The story begins as Calvin, a worker at a wastewater treatment plant, accidentally steps into some sewage. This is a great metaphor for the entire story, as poor Calvin seems to have stepped into a few messes. Calvin likes his coworker Dave Lott, but doesn’t particularly like spending time with the guy. Jill (Calvin’s wife) wants another child, which is most retrograde to Calvin’s desires. Life only gets worse when Dave Lott dies from a terrible staph infection—an occupational hazard for wastewater treatment workers, of course. Calvin and Jill offer Dave’s first wife and his fifteen-year-old daughter a place to stay for the funeral, which is a depressing affair. To Calvin’s eyes, daughter Jennifer is an odd bird; he takes the young woman to see her Dad’s office. In an odd and suspenseful scene, Jennifer disappears. Calvin finds her in a supply closet where they share a fascinating moment of intimacy. Stasis re-establishes itself after Calvin gets home. Jill mistakes his existential angst and cry for help for arousal and the reader is left to wonder what will happen to the characters in the future.

The great short story writer Lee K. Abbott once pointed out, correctly, that there aren’t too many stories about the workplace. Isn’t this odd? So much of our lives take place in an office or on the work site, but such settings seem to be underrepresented in fiction. Ms. Pneuman points out in her author’s note that she once worked in a support capacity for wastewater treatment personnel in Indiana. I certainly believe that she has depicted the sewage plant faithfully; I can imagine the concrete maze of water and the unpleasant stench. Honestly, why shouldn’t sewage plant workers have their say in fiction? As writers, one our responsibilities is to explore new worlds and shed light on the fringes of humanity. After all; who wants to read the same story about the same people over and over again?

It’s very tempting to write about writers or artists or some other job that stands in as a placeholder for “writer.” (I’ve done it…have you?) It would be a shame to miss out on all of the great details and good stories that come out of the workplaces we know. (Even if we don’t love them.) Most of us have spent time in hourly retail jobs, right? What are the unique stories of the unique people who fill these positions?

Here’s an example. One of the latest “dumb things young people do” is “firebombing.” Crummy people will go through a restaurant drive-thru window and throw stuff on the worker staffing the post. One jerk took the concept to a new low; he squirted hot sauce in the worker’s eyes. Here’s a news report about it.

Maybe the video gets your “What would that be like?” going. What if this wasn’t the worst part of the character’s day? What if he knew the jerk? What if the jerk missed and the worker simply had had enough? What restaurant policies might change after the attack? We’ll never know unless someone sets a story in a fast food joint.

The climax of the story, it seems to me, is the scene in which Calvin and fifteen-year-old Jennifer…share a moment in the darkened office. Now, I’m always up for “weirdness.” Is a story interesting if a character or situation is “just kinda normal?” The first time I read the story, I definitely picked up on the fact that Ms. Pneuman was putting Calvin and Jennifer together in the narrative. The instant the young lady arrives, Ms. Pneuman is careful to make it clear that Calvin is thinking about her and is preoccupied. Without such clues, Ms. Pneuman may not have made the scene of intimacy very realistic. Anything will make sense, so long as you make it clear that the events make sense in the context of the world you’ve created.

What Should We Steal?

- Train your focus on the world of work. Think of how many hours your characters spend in the workplace. Thirty? Forty? Fifty or more? During that time, your characters are interacting with other people, suffering setbacks and feeling resentment growing in their hearts. Consider dramatizing these oft-overlooked moments of your characters’ lives.

- Ensure that your weirdness makes sense in the context of the story. Think of The Twilight Zone. (It’s something I do all the time.) So much crazy stuff happens on that program, but we buy it. Why? Because Rod Serling clearly established the rules of The Twilight Zone. Okay, aliens don’t turn the lights on and off in the real world…but we believe that it can happen in the world Mr. Serling created for us.

Short Story

2011, Angela Pneuman, Best American 2012, Material, Ploughshares