Title of Work and its Form: Holdup, novel

Author: Terry Fields

Date of Work: 2007

Where the Work Can Be Found: The book was published by Square Fish (a Macmillan imprint). You can purchase the book online or at a local independent bookstore.

Bonuses: Here is an appearance that Ms. Fields made on the Book Bytes for Kids podcast in which she discusses Holdup. (She seems like a very kind and cool woman!) Here is a short essay Ms. Fields wrote for authors who want to get their books to a wider audience.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Narrative Structure

Discussion:

This very cool book recounts the points of view of nine people whose lives are forever entwined during a Burger Heaven robbery. Two of the characters are robbing the place and the rest are employees or customers who deal with the event. Ms. Fields introduces the reader to a wide range of characters: the type-A young woman who isn’t supposed to be there today, the outsider who just wants to be seen for his personality, an older woman who tries to help a bright young man see that he can improve his life. In terms of summary, that’s really enough. Read for yourself to discover all of the twists and turns in the narrative.

Ms. Fields structures the book in an interesting way. Each of the characters has a say and offers their perspective (and exposition) in their own unique voices. The type-A young woman evokes empathy with her struggle at being a go-getter while also enjoying life. The drive-thru master breaks your heart with his belief that he’ll never be good enough to go to college. The structure (reminiscent of Tom Perrotta’s excellent Election) results in an interesting twist on third and first person prose. Each of the sections are written in the first person, allowing Ms. Fields to decrease the distance between the character on the reader. The cumulative effect of all of these first person accounts indicates a third person narrator behind it all. Who is pulling the strings? Who (other than Ms. Fields, of course) decides which characters speak and when? Who decided how much of the narrative would take place before the robbery? Ms. Fields has her cake and eats it too; all of the passion and conversation of the first person POV with the narrative flexibility of the third person.

This is a book about high schoolers who, we must admit, are pretty much adults. (Particularly when they commit violent crimes.) I haven’t finished my Young Adult book-who am I kidding; I likely never will-so I don’t know how much resistance Ms. Fields got from her publisher or from the marketplace for employing violence in the book and hinting toward sex and drugs. (I found a kind review from School Library Journal that seemed pretty accepting of the book’s themes.) Ms. Fields is smart enough not to talk down to young people or to pretend that sixteen-, seventeen- and eighteen-year-olds aren’t having sex and getting into trouble. The book feels real because the characters are drawn with verisimilitude. I have difficulty enjoying bowdlerized works.

Quick explanation: We get the term “bowdlerized” from Thomas Bowdler, who rewrote Shakespeare to make it more “appropriate” for family audiences. In the course of doing so, Mr. Bowdler gutted the plays of meaning. The same principle applies when you watch Goodfellas, one of the best movies ever, on television or on an airplane. Instead of watching the 146-minute masterpiece depicting gangsters using gangster words, you can watch a fifteen-minute short film about a man named Henry Hill, who worked at an airport and made spaghetti sauce.

See why bowdlerized works lack verisimilitude? (The appearance of reality in fiction.) I love that Theresa understands she’s attractive, but refuses to accept being touched by the gross grill guy. I love that Dylan really seems to have the narcissism of a hardened criminal. I don’t want to ruin anything, but there is violence in the story…AS THERE SHOULD BE. It’s a book about a fast-food robbery. Stuff needs to happen.

What Should We Steal?

- Employ a third person narrator that really consists of many first person ones. When you assemble many first-hand accounts, get all of the benefits of one-on-one conversation with the powers of second-hand accounts.

- Avoid bowdlerizing your own work. If you’re writing about a gangster, he or she probably must swear and shoot people. If you’re writing about teenagers, they are going to have sex…or at least they’ll really WANT to.

Novel

2007, bowdlerize, Holdup, Narrative Structure, Terri Fields, Young Adult

I’ve pointed out how fun and generous Matt is in my previous coverage of Odd Men Out. (In case you missed them, here are What We Can Steal From Odd Men Out and GWS Inside the Craft: Matt Betts.) Matt’s book is fun and engrossing and can be purchased at Raw Dog Screaming Press and Amazon.

In conducting the very first Great Writers Steal interview, I wanted to ask Matt about his craft and about his own literary borrowing habits. As you’ll see, his responses are both thoughtful and helpful to the rest of us.

NOTE: Please be aware that the interview may contain mild spoilers. I don’t think you’ll really be spoiled; Odd Men Out‘s blurbs make it clear which baddies the good guys must fight. Further, it really shouldn’t be a shock that a novel-an adventure/science fiction/horror novel, no less-would have a climactic battle 80% of the way through. One sensitive spoiler is concealed with invisotext. Click and drag over the text if you want to see it.

When did you begin writing and how important have the science fiction/horror communities been to you, both in terms of inspiration/stealing and in helping you improve your work?

When did you begin writing and how important have the science fiction/horror communities been to you, both in terms of inspiration/stealing and in helping you improve your work?

You know, I was writing in high school. And college, but I didn’t really get serious until the last ten years or so. In college, I had professors that were pretty much against anything genre, so I was very discouraged. I stopped writing for 5-6 years because of it.

You know, I was writing in high school. And college, but I didn’t really get serious until the last ten years or so. In college, I had professors that were pretty much against anything genre, so I was very discouraged. I stopped writing for 5-6 years because of it.

I’ve always been I to sci-fi and horror. But when I started working with writing groups here in Columbus [Ohio], I usually worked with non-genre writers. It kind of worked out that way. We all learned our crafts together.

I owe a lot to the horror and sci-fi I read, though. King was a big favorite, Anne Rice too. While I consider myself more of a sci-fi writer, I read a lot more horror.

I spent a lot of time in college, while my professors were telling me how terrible genre fiction was, reading a lot of horror and suspense anthologies and seeing how stories worked. How characters worked, etc. I still have one of those anthologiess in my collection.

What are the qualities of genre writers that “literary” writers might most want to steal?

What are the qualities of genre writers that “literary” writers might most want to steal?

I think both types of writers can learn from each other. And I think that’s why you see so many novels with a foot in each camp that climb the charts and do well with readers.

I think both types of writers can learn from each other. And I think that’s why you see so many novels with a foot in each camp that climb the charts and do well with readers.

The pacing of genre novels tends to be faster than literary. Usually. One of my favorites is Faulkner. My dad has always been a fan and it rubbed off on me.

It’s interesting that you say that about pacing; in reading Odd Men Out, I was reminded of the short-chapter style of Alex Cross books, The Da Vinci Code and other “thriller” novels. Did you have any specific structural models for the book?

It’s interesting that you say that about pacing; in reading Odd Men Out, I was reminded of the short-chapter style of Alex Cross books, The Da Vinci Code and other “thriller” novels. Did you have any specific structural models for the book?  You know, I can’t say that I had particular structural models for the book as far as literary models. I did have that pace in mind from some of the old serial novels and serial movies. The idea that each chapter left the reader or viewer with a cliffhanger or minicliffhanger.

You know, I can’t say that I had particular structural models for the book as far as literary models. I did have that pace in mind from some of the old serial novels and serial movies. The idea that each chapter left the reader or viewer with a cliffhanger or minicliffhanger.

When I went back and did some of the re-editing, I looked at my chapters and tried to use the length of the chapters to my-and the story’s-advantage. I deliberately put some really short ones together and stuck some longer ones in the middle. I found it helped propel story forward better.

I hate to keep fawning over Elmore Leonard, but he works with varying lengths of chapters well. He certainly showed how it was possible to use that to the plot’s advantage.

I did notice that the sections during the action setpieces were shorter, speeding the narrative up and allowing you to switch between the perspectives of characters who were in different places. To what extent were you influenced by these kinds of sequences in action and science fiction films?

I did notice that the sections during the action setpieces were shorter, speeding the narrative up and allowing you to switch between the perspectives of characters who were in different places. To what extent were you influenced by these kinds of sequences in action and science fiction films?

Quite a bit. I think I’ve mentioned that I’ve been a pop culture junkie for a long time. I a huge fan of action movies - so much so that I claim Die Hard and Lethal Weapon as my two favorite Christmas movies. But watching well-made action and suspense movies really influenced me. I love when a director and a script can switch between the bad guy and the good guy effectively. An audience gets that look at what could happen, and can anticipate how the hero is going to get out of it.

Quite a bit. I think I’ve mentioned that I’ve been a pop culture junkie for a long time. I a huge fan of action movies - so much so that I claim Die Hard and Lethal Weapon as my two favorite Christmas movies. But watching well-made action and suspense movies really influenced me. I love when a director and a script can switch between the bad guy and the good guy effectively. An audience gets that look at what could happen, and can anticipate how the hero is going to get out of it.

Back in college, there was a video store (yes, actual video tapes) that had some ridiculous deal, like 5 movies for 5 dollars, but you could only have them for one night. My roommate and I would go there several times a week. At first we were renting all the good movies we heard about, but when those ran out, we started renting the bad ones. Eventually, we were renting movies just to find one good thing about them. A good line, a good chase, cinematography.

It was actually a good study in story. And characters. And plot. I really got to look at what made a movie tick.

I love Die Hard and especially Lethal Weapon. What do you see as the advantages and disadvantages of casting your final battle with the dragon-literally in this case-in prose instead of celluloid?

I love Die Hard and especially Lethal Weapon. What do you see as the advantages and disadvantages of casting your final battle with the dragon-literally in this case-in prose instead of celluloid?  Ugh. I was starting to think it was a bad idea when I got to that. I actually wrote some of that scene early on, because I had had a specific part of the scene stuck in my head for a while. I wrote a few pages around that specific part, and then went back to writing parts earlier in the book. I would peck away at the dragon scene bit by bit. It was tough to choreograph. Everything and everyone in the book converged around that scene. So, I was working from different POVs and slightly different timelines, etc. It got so I dreaded going back to it. But I’d plucked away at it enough that by the time I got to it chronologically, the skeleton of the scene was there.

Ugh. I was starting to think it was a bad idea when I got to that. I actually wrote some of that scene early on, because I had had a specific part of the scene stuck in my head for a while. I wrote a few pages around that specific part, and then went back to writing parts earlier in the book. I would peck away at the dragon scene bit by bit. It was tough to choreograph. Everything and everyone in the book converged around that scene. So, I was working from different POVs and slightly different timelines, etc. It got so I dreaded going back to it. But I’d plucked away at it enough that by the time I got to it chronologically, the skeleton of the scene was there.

So, really, the disadvantage was having everything come to that. All of the good guys and bad guys, ancillary characters, they were pretty much all there. If one of the plotlines didn’t work, I was in trouble. I’m honestly not sure what the advantage to that situation was. Looking back, it seems like I just made more work for myself!

But I think it worked out, thankfully! I had so many versions before the final. It was really like choreographing a fight scene for the stage. I had a friend in college who did fight choreography and I was always fascinated by what went into making it look good. That’s kind of how I had to approach it here.

Well, speaking of movie terminology[…spoiler…] did you intend the “device” to be a MacGuffin in the story? The device certainly figures into the climax of the book, but I was a little surprised that you used it in such a passive way.

Well, speaking of movie terminology[…spoiler…] did you intend the “device” to be a MacGuffin in the story? The device certainly figures into the climax of the book, but I was a little surprised that you used it in such a passive way.

It really was.[…spoiler…] I really planned on it being something that actually carried on a bit more, maybe even into another novel, but in the end I really saw it as a MacGuffin that was going to bring everyone together for the rest of the story. I had vision of the glowing briefcase in Pulp Fiction as they were trying to open the device and figure it out. It was meant to be a means to an end for the Sons of Grant, and a reason to give chase for the others. The origins of the device also left open a wealth of other types of devices from Dr. Poley in the future.

It really was.[…spoiler…] I really planned on it being something that actually carried on a bit more, maybe even into another novel, but in the end I really saw it as a MacGuffin that was going to bring everyone together for the rest of the story. I had vision of the glowing briefcase in Pulp Fiction as they were trying to open the device and figure it out. It was meant to be a means to an end for the Sons of Grant, and a reason to give chase for the others. The origins of the device also left open a wealth of other types of devices from Dr. Poley in the future.

It also left the possibility that the device didn’t even work. Which could be explored in the future. I’m not saying it didn’t, but without the evidence, the OMO could well think it. There was this great scientist and he built a lot of fantasic things, but were they all reliable? I may explore that idea further. If not in a novel, maybe a short story. Of course, I didn’t mean to build a plot device that was thin or fulfilling. I wanted something just dangerous enough to be interesting and hopefully serve as a little bit more than something that just didn’t end up going boom, you know?

Very interesting! I do wonder what other devices were created in the alternate United States. One of the challenges of alternate history, it seems to me, is clearly delineating the “break” with our reality and filling in the differences in the world of the narrative as opposed to ours. You definitely offer us glimpses of what happened to the President and how the fighting in the Civil War was suspended; what was your thinking in deciding how much to tell? I’m not sure you mention a concrete year for the story.

Very interesting! I do wonder what other devices were created in the alternate United States. One of the challenges of alternate history, it seems to me, is clearly delineating the “break” with our reality and filling in the differences in the world of the narrative as opposed to ours. You definitely offer us glimpses of what happened to the President and how the fighting in the Civil War was suspended; what was your thinking in deciding how much to tell? I’m not sure you mention a concrete year for the story.  I don’t come right out and name a year. That was a criticism of one of my early critiquers. So I went back and planted clues, but those weren’t even concrete. I was aiming for the early 1890s. I mention that the first battle of Gettysburg happened as normal, and then one with the chewers at Gettysburg. So, those hints, along with a few others, set the timeline for this. In the next book, I might start with a big stamp on the cover page that says 1895, or whatever I make it.

I don’t come right out and name a year. That was a criticism of one of my early critiquers. So I went back and planted clues, but those weren’t even concrete. I was aiming for the early 1890s. I mention that the first battle of Gettysburg happened as normal, and then one with the chewers at Gettysburg. So, those hints, along with a few others, set the timeline for this. In the next book, I might start with a big stamp on the cover page that says 1895, or whatever I make it.

It was interesting once I made that break with their technology. I found it fun to play with what actually happened and what I wanted to happen. I found myself accelerating the advances in weapons, which seemed logical considering they were facing the chewers, and decelerating their civilization, since it was being destroyed by the chewers.

For whatever it’s worth, I didn’t mind not having a date. Cyrus and Bethy aren’t really thinking about the year or anything; they’re just dealing with the circumstances in which they find themselves. I got the point that we were in Reconstruction and things are very different. My two cents for fun. Maybe I benefited because I wasn’t thinking, “Gee, I wonder if Tilden and Hayes were in the 1876 election in this timeline.”

For whatever it’s worth, I didn’t mind not having a date. Cyrus and Bethy aren’t really thinking about the year or anything; they’re just dealing with the circumstances in which they find themselves. I got the point that we were in Reconstruction and things are very different. My two cents for fun. Maybe I benefited because I wasn’t thinking, “Gee, I wonder if Tilden and Hayes were in the 1876 election in this timeline.”

Thanks! I actually enjoyed not setting it firmly in a certain date. It kept the story ambiguous for the reader. I saw the West as a pretty desolate wasteland when I started. I softened that a bit as I went, with more pockets of people than originally intended. I wondered at some point whether any of those pockets would agree on what year it was if they got together to talk about it. So, that’s another reason I left it in a general area.

Thanks! I actually enjoyed not setting it firmly in a certain date. It kept the story ambiguous for the reader. I saw the West as a pretty desolate wasteland when I started. I softened that a bit as I went, with more pockets of people than originally intended. I wondered at some point whether any of those pockets would agree on what year it was if they got together to talk about it. So, that’s another reason I left it in a general area.

Finally, what do you hope that fellow writers will steal from you after they read Odd Men Out?

Finally, what do you hope that fellow writers will steal from you after they read Odd Men Out?

Oh. What do I hope people will steal from me? That’s a good question. I learned/stole/lifted so many things from other writers. I hope that, in the long run, writers will write whatever they want and not hold anything back because it isn’t marketable or it doesn’t fit into a nice category. I wrote a story that I enjoyed, first and foremost, and it just happened to have sci-fi, steampunk, horror, alternate history, a Godzilla-like monster, zombies and maybe a few more things tossed in for good measure. But it was the story I wanted to tell. There were drafts where I thought of eliminating the zombies and others where I got rid of the lizards. In the end, it wasn’t satisfying to me, so I kept working on making it a better story. The right editor and publisher came along when I got it right. And with their help, we made it even better, I think.

Oh. What do I hope people will steal from me? That’s a good question. I learned/stole/lifted so many things from other writers. I hope that, in the long run, writers will write whatever they want and not hold anything back because it isn’t marketable or it doesn’t fit into a nice category. I wrote a story that I enjoyed, first and foremost, and it just happened to have sci-fi, steampunk, horror, alternate history, a Godzilla-like monster, zombies and maybe a few more things tossed in for good measure. But it was the story I wanted to tell. There were drafts where I thought of eliminating the zombies and others where I got rid of the lizards. In the end, it wasn’t satisfying to me, so I kept working on making it a better story. The right editor and publisher came along when I got it right. And with their help, we made it even better, I think.

I’m not sure that exactly answers your question. I love mash-ups and crazy mixes and I’d love to see more. And I’d like to see more authors following their muse.

Novel

GWS Interview, Matt Betts, Odd Men Out, Raw Dog Screaming

When I first e-mailed Matt to arrange the first GWS interview, I had no idea that he would be so generous with his time and his thoughts. Odd Men Out is a fun book-available now at Raw Dog Screaming Press and Amazon-and the book certainly seems like the kind of work that would emerge from a curious and engaging guy like Matt.

In the course of telling him what I might ask about during our interview, I hadn’t expected him to offer thoughtful and lengthy responses. I share them with you (with his permission, of course) to offer a look into the way Matt approaches his work and solves the problems that confront us all in some way.

Odd Men Out is an adventure/science fiction/horror/steampunk novel, and that means that Matt needed characters to fulfill certain dynamics in addition to seeming like real people. I mentioned that two of the characters seemed to have echoes of Han Solo and Luke Skywalker. (EVERY story that resembles Odd Men Out‘s narrative will have these resemblances, of course.) Here are Matt’s thoughts on creating dynamics between characters and making them his own.

Though, when you mention Cyrus and Lucy being Star Wars analogues, I can see where you get that, but it was never a thing I really thought about. I love Star Wars - it was one of the first movies I remember seeing in a theater, so it heavily influences me, but I never thought “here’s my Han Solo, here’s my Luke.” I love Firefly and Aliens and comic book teams like The Avengers and the X-Men. I started writing the book thinking of those great casts and ensembles and wanted to have one of my own. I wanted believable adventurers who legitimately had reasons not to trust each other and not to get along. So, as much as I love Star Wars, it really never entered my mind as I wrote Odd Men Out. There were so many steampunk, old west, alternate history things going on, that actual outer space-type science fiction really never came into the process…

…It was strange that I never considered the movie while writing Odd Men Out, or even when I was editing it. I can certainly see correlations in the functions of some of the characters now. But it was weird that it hadn’t come to me before that.

I think Matt is pointing out that we may have some explicit inspirations for our work, but there are always influences that we don’t think about consciously.

Matt’s book is set in an alternative United States in which the emergence of zombie-like creatures changes American priorities. (It was hard enough to fight the Civil War…can you imagine doing so with monsters in the mix?) Anyone who writes about zombies or vampires or werewolves or spaceships or aliens must set their own rules for how THEIR iterations fit in with all of the others. There are approximately eleventy trillion zombies in media right now; how did Matt approach creating his “chewers?”

You’re absolutely right about the idea of creating rules for the various ‘monsters’ and for the science in the book. I did kind of have to pick and choose whose mythology I wanted to follow and what I wanted to create of my own. Zombies are certainly weird, as they have become so popular. There are so many interpretations, that I found myself gravitating toward the more traditional versions, if such a thing exists. I looked more at the physiology of things like the original Night of the Living Dead, for the slow-moving, shambling monsters, rather than the running, screaming zombies we’ve seen in more recent films. The main reason was purely story-related. I needed my monsters relatively slow to give characters more of a fighting chance.

I started the novel long before The Walking Dead was on televison, and I never really cared for the graphic novels so much, so most of my zombie influence came from the movies like Night of the Living Dead and Dawn of the Dead. I remember watching some of those when I was in high school and having my eyes covered because they scared the crap out of me. Now, the book went through several rewrites, and by the time I was doing those, The Walking Dead was on TV and I was watching those first seasons and loving them. But to me, Odd Men Out wasn’t, in my mind, ever a zombie novel. I meant to treat them at a fact of life, something in the background. An early note I had was that they were ‘carpet’ in the landscape. I’m not sure what that would mean to a reader, but it was an important note to me.

Matt makes a very important point: in a way, the unique circumstances of your world shouldn’t be a big deal. The reader may get through the first few chapters and think, “Zombies! Oh my! I wonder what happened!” Cyrus and Lucinda and Tom and Cashe do not think that way about the ghouls in their midst. They’re really just part of the furniture, so to speak.

It’s a sad truth in adventure-type stories: characters must die. Even characters that you and your audience like. Too bad. Here is how Matt approached deciding who was going to die and when. (Don’t worry. No spoilers.)

You mentioned useful characters dying and that was kind of a big deal as was editing. I did some major edits and rewrites of the story along the way and there were more characters that died in one of the last versions before the final. In fact, there were actually more characters introduced in the early (Turtle) chapters that lived, but they were later cut to streamline the story. There were survivors that were around basically to make Cyrus and the reader remember what happened on the Turtle from time to time and really, it wasn’t necessary. But in that working draft, some other important characters didn’t live to see the last chapter. I wasn’t always thinking of a sequel to the book and who I needed to keep around for it, it was really just a balancing act to see who I could lose and still be happy with the ending. I didn’t want a senseless death, but I wanted the reader to be a little shocked by losing someone that they didn’t expect. I didn’t want the reader to be comfortable with thinking they knew what would happen. There was a “Hamlet” version of the ending where every other character died. It was fun, but ultimately unsatisfying to the story itself.

Well, not everyone has an eye on a sequel (I have low self-esteem), but I love how the prospect worked into Matt’s thought process. Writing is all about making choices; some characters die because the story requires them to do so and others bite the bullet because it’s a necessity to the writer.

And how do we streamline those choices? Editing. This is not my favorite thing to do, but here is how Matt approached tuning up Odd Men Out:

I don’t think I consciously took this from any particular movie or book, but I remember being surprised by certain deaths Elmore Leonard’s works.

Elmore Leonard has this credo about his writing, and in doing my edits, I tried to stick close to it. He says, “Try to leave out the part that readers tend to skip.” When I was editing, I had several readers mark up the manuscript, and whenever someone told me a section or paragraph was too flowery or too much exposition, I ended up cutting it 9 times out of 10. I think I actually cut a couple of small chapters that way. I definitely cut out a number of point of views that way. I think I have the story from 4 POV characters now. In early drafts, it was more like 6, maybe 7. It made the the book too busy and I combined some characters and eliminated others.

Another piece of writing advice I followed is the old admonition to “Kill your Darlings.” The idea being that you can’t be afraid to delete what you consider your best work, if it really isn’t helping your story. I sat with my finger hovering over the delete button for a long time on some of my favorite passages. It hurt like crazy to cut them, but it certainly made the story stronger. It absolutely applied to killing off some of the characters that I loved as well.

I also applied that advice in a somewhat warped way to my main character, Cyrus. I wrote a note in his file specifically saying “Wound your Darlings.” I put Cyrus through hell in this story. Things happen to him. Some are by choice and others just happen, but it became a sport to see what I could actually do to him in the novel.

See why I called Matt “thoughtful” and “generous?” As I’ve said a trillion times, there is no step-by-step checklist you can follow in order to improve your writing. Craft advice must percolate inside our brains; after enough time, you’ll be able to make use of the lessons you didn’t know you were learning. What do you think of Matt’s experience and process? How does reading about his thoughts on craft affect your own?

Novel

2013, GWS Inside the Craft, Matt Betts, Odd Men Out, Raw Dog Screaming

Title of Work and its Form: Odd Men Out, novel

Author: Matt Betts (on Twitter @Betts_Matt)

Date of Work: 2013

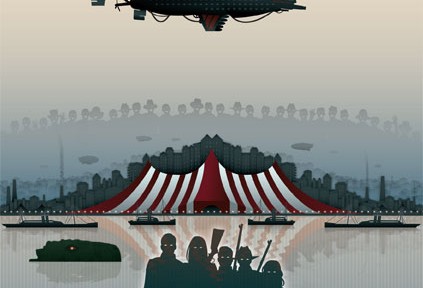

Where the Work Can Be Found: The book can be purchased from Raw Dog Screaming Press. You may also want to purchase the book on Amazon. (The e-book is VERY reasonably priced as of this writing!) Check out the cool jacket art by Brad Sharp:

Bonuses: Here is the Goodreads page for Odd Men Out. Here‘s a brief but favorable review of Odd Men Out from Publisher’s Weekly. Here‘s a brief biography of Mr. Betts.

Bonuses: Here is the Goodreads page for Odd Men Out. Here‘s a brief but favorable review of Odd Men Out from Publisher’s Weekly. Here‘s a brief biography of Mr. Betts.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Narrative Momentum

Discussion:

What a fun book! Odd Men Out takes place during Reconstruction-but not in the history we remember from high school. Cyrus Joseph Spencer and the crew members of his “Turtle” (a five-story, six-legged machine that ferries people where they want to go) inhabit an America that has developed steampunk technology. And in which giant lizards are a threat. And in which a precarious truce replaced the open warfare of the Civil War. Oh, and don’t forget the “chewers,” humans who have succumbed to a virus that transforms people into zombies. Matt asserts that he’s a pop culture junkie, and that’s a great way to think about the book. Odd Men Out is a slam-bang adventure story that has all of the excitement and twists of a summer blockbuster. There are a few narrative threads in the book. Cyrus and Lucinda deal early on with the loss of their Turtle and join up with Cashe and the crew of the United Nations of America ship Leonidas Polk. All the while, Tom Preston, member of the Sons of Grant, takes advantage of his employer, entertainment impresario Umberto Cantolione. The book’s plot hums along quickly and the characters’ lives converge, as you might imagine, on a big, awesome battle that determines the fates of everyone involved.

As I pointed out, Matt really keeps the plot chugging along. The book consists of 91 chapters of varying lengths. Each section is anchored by the third person narrator, taking the perspective of each section’s focal character. During the climactic final battle, the sections are very short. The chapters are, by contrast, much longer during some of the quieter scenes between the high points. When I read the book, I was reminded of the kind of structure that is employed in books such as The Da Vinci Code or (to a lesser extent) The Firm. When the chapters are relatively short, the reader has less time to get bogged down in the narrative. The BIGGER ISSUES of the book are often stuck more firmly in your mind. For example, when you read The Firm, you can’t help but wonder: Will Mitch McDeere enjoy his life at the firm? What happened with those other lawyers who died? Oh no! I can tell something is wrong with this firm; what will Mitch do? Varying the lengths of your chapters is one of the ways in which you can shape how your reader digests your work and direct their understanding of it.

Matt had a TON of exposition that he needed to release in the book. After all, he was working in a world that was very much of his own creation. (The characters in The Firm, after all, were running around a world similar to ours, right?) The narrator does some “telling” in the book, but Matt also came up with fun ways to fill in the gaps. At one point, the slimy Tom Preston finds a notebook/diary that was kept by people who were witnesses to some of the “fun” and “crazy” events that occurred when the Odd Men Out world diverged from real history. Matt’s characters simply can’t know a lot of that information, so I enjoyed that he found a way to get it into the book.

As I mentioned, the book contains Matt’s take on zombies. I don’t know how he approached naming the creatures, but I could tell from the prose that he was very careful not to use the same word to describe the antagonists. So instead of writing “chewers” a thousand times, he sprinkled in words such as, “undead,” “the dead,” “ghoul” and “attacker.”

This principle is particularly prominent in sportswriting and with play-by-play announcers. How often can you say that Miguel Cabrera “hit” the ball? Instead, here’s what Miguel Cabrera does to the ball:

- wallops

- crushes

- knocks

- pounds

- taps

- slams

- ticks

- slaps

- rockets

- loops

- bunts

- powers

- jacks

- fouls

Each of these words kinda mean the same thing, but offer some very important distinctions. Be on the lookout for synonyms that you can use to add characterization and intensity, as well as to describe.

Above all, Odd Men Out is FUN. Isn’t fun one of the reasons we get into writing in the first place? “Genre” isn’t necessarily a bad word, either. Let’s consider a list of writers who have written in genres that are sometimes frowned upon:

- Kurt Vonnegut (science fiction)

- Shirley Jackson (horror)

- Stephen King (horror, fantasy, science fiction)

- Ray Bradbury (horror, science fiction)

- Harlan Ellison (science fiction)

- Ursula K. Le Guin (science fiction)

- Jane Austen (romance, steampunk, horror)

Can anyone honestly say that these writers are somehow lesser because they do literary work that can sometimes be considered “genre?”

What Should We Steal?

- Vary the lengths of your chapters. Action and suspense stories can benefit from a structure that boasts many small chapters.

- Experiment with a number of different ways to release exposition. Perhaps your character keeps a journal. Maybe there’s a crucial photograph in your piece that establishes an important plot point.

- Brainstorm synonyms for some of the words in your work that could be overused. Not only do you avoid boring people, but you force yourself to use words that are more powerful and descriptive.

- Have fun and don’t be afraid of the “g-word.” Just because a story features spaceships, zombies or long-lost loves doesn’t necessarily mean that a work isn’t “good” or “literary.”

Novel

2013, Alternate History, GWS Interview, Matt Betts, Narrative Momentum, Raw Dog Screaming

Title of Work and its Form: Penn & Teller, magic act/writers/producers, etc.

Author: Um…Penn Jillette and Teller. (Mr. Jillette can be found on Twitter @pennjillette and Mr. Teller can be found @MrTeller.)

Date of Work: The pair have worked together since 1975.

Where the Work Can Be Found: Penn & Teller have a regular gig in their theater in the Rio All-Suite Hotel & Casino in Las Vegas. If you are in the area, go and see them several times. Mr. Jillette and Mr. Teller always have a lot going on. You may be able to keep up at this Facebook page. Mr. Jillette has a STELLAR podcast called Penn’s Sunday School. Penn and Teller are always doing interesting things like this: a magical collaboration with a dance company.

Bonuses: Penn & Teller are on a lot of talk shows. Why do producers enjoy booking them? Because P&T are always interesting and they always come prepared. Here is an appearance the duo did on Letterman:

And here’s a great appearance they did with Conan.

Here is where I first took note of Penn & Teller. (At least I think that’s the case. I was pretty young.) Spy Magazine (one of the best ever) allowed the magicians to tell you how to pull a mean prank on your closest friends.

Discussion:

I’ve been a big fan of Penn & Teller for a very long time and for a number of reasons. Only in the past decade or so have I come to understand more deeply why they are so amazing and have been relevant for so long. Penn & Teller teamed up nearly forty years ago; Penn had no formal post-secondary education and Teller had a degree in Latin and taught the classics. Look at what Penn says in this Q&A starting at around 20:30:

Penn makes a very interesting point. The two men have a relationship that is primarily about respect and not love or extreme affection. In a way, the respect we have for writing partners and fellow scribes is more important than love. Respect is a sentiment that is earned based upon evidence, while love can be inspired by irrational thinking. Think about your experiences with your favorite teachers. I remember my first workshops at Ohio State quite well; I sat down in the workshop room with a great deal of respect for folks like Lee K. Abbott simply because of what he had accomplished in the literary world. Over the first few workshops we shared (and the subsequent years I got to work with him), my respect deepened based upon his skill and the way he related to everyone. That kind of sentiment doesn’t go away very easily. Compare that to a crush you had in high school; those feelings are far more precariously perched in our hearts. If you are lucky enough to work with a partner, bear in mind that the longevity of the arrangement will be determined by your commitment to the work, not to each other.

I’ve been a fan of Penn & Teller’s Bullshit for many years. I even use it in my classes because Penn & Teller are masters of rhetoric. (And why shouldn’t they be? Magicians MUST be able to convince you of all kinds of things that aren’t necessarily real.) The program is a kind of documentary series; in each episode, the pair take on an issue and point out, as they put it, the “bullshit” involved. Do I always agree with them? Of course not; no one agrees with anyone else 100% of the time. (Not even Penn with Teller and vice versa.)

As you can tell by the abrasive-to-some title, Bullshit pushes some away with its title and still others with the hosts’ strong stances on controversial issues. Some, for example, contend that there is proof that childhood vaccines have contributed to the recent rise in autism diagnoses. Penn & Teller point out very clearly that there is no science to support such a hypothesis and spend 28 minutes employing ethos, pathos and logos to dismantle the claim from all sides. Here’s the introduction to the episode:

By all means, please buy the program on DVD or stream it. Even if you disagree with Penn & Teller on this point or any other, the two men (and their researchers and co-writers) create works that result in both light and heat. Great writing (and magic) should address our intellect AND our emotions. A great book teaches us something about the world AND makes us feel something real.

Penn & Teller do a lot of dangerous tricks that you definitely shouldn’t try to recreate at home. As the duo notes, it can take YEARS for them to perfect a trick enough to perform it for a real audience. They spend a lot of time and money just PRACTICING and TRYING and HOPING that a trick will work out. If it doesn’t work out in the end, they abandon it. Is this a bad thing? Not necessarily; their infrequent failures teach them important lessons.

I love that Penn & Teller, like so many magicians, immerse themselves in the history of magic and the magic world at large. The same is true with comedians: most great comedians know everything about the field. Great writers? They are very hard to stump in a discussion about literature. Penn & Teller made a whole documentary in which they went in search of the history of “the cups and balls,” one of the basic tricks that every magician learns. This is how everyone who dabbles in prestidigitation learns their loads and steals and how to make their hands move faster than the audience’s eyes. The pair ended up in Egypt in an ancient building whose walls feature a depiction of what may be a person doing the cups and balls trick…thousands of years ago. How do they honor the tradition? They perform their own version:

Look at this beautiful essay Mr. Jillette wrote for the Huffington Post. Here is a recording of Mr. Jillette reading his essay.He was competing on Celebrity Apprentice, a program that some folks wouldn’t believe possible of creating something that is artistically beautiful. That notion was blown out of the water when Mr. Jillette and Blue Man Group decided to change what Celebrity Apprentice COULD be. During a fundraising task, most contestants will simply have a rich celebrity friend bring by a big check. Everyone oohs and ahhs about selling Gary Busey’s painting for $50,000 and boom. Done. Instead, Blue Man Group, the entertaining and experimental performance art group, decided to bring in money, but to do it their way. The Blue Men brought in money, to be sure, but did so in a giant balloon and accompanied by eccentric pomp and circumstance. The balloon was then burst, creating yet another sight that most people have never seen: legal tender fluttering around the streets of New York. Life, they seem to say, should be lived for enjoyment and to glorify beauty.

For whatever reason, Penn & Teller are sometimes self-deprecating when describing themselves. They’re not just carny/renaissance fair folks; they’re smart men who devote themselves to all of the many things that are important to them. Mr. Jillette has written several books, some with Mr. Teller. Mr. Teller directs plays and makes use of his magic skills when appropriate…I’m sure that Macbeth’s dagger looked great onstage.

Mr. Teller inspired me in a very cool way. In 1997, the gentleman published an essay in The Atlantic. In high school, Mr. Teller read “Enoch Soames: A Memory of the Eighteen-Nineties,” by Max Beerbohm. Soames is a poet who wishes to know if his work will have any effect on literary history, whether all of his modest scribbling will be in vain. The Devil (of course) offers him a deal: Soames will spend eternity in Hell in exchange for a trip to the Round Reading Room of the British Museum in 1997, where Soames will see evidence of his legacy.

Now, I don’t want to ruin both “Enoch Soames” or Mr. Teller’s piece of creative nonfiction. If you read the Atlantic article, you will see the same kind of glorification of art and the artistic impulse that Mr. Jillette described in his piece. Why do I mention all of this? The Atlantic piece struck me deeply and a great story idea popped into my head, which I promptly wrote. I usually hate the stuff I write (a defense mechanism?), but this story turned out pretty well, perhaps the best I’ve ever written. What is the big takeaway? Artists have chosen a difficult life, but a very rewarding one. After all, we are fortunate enough to be the people who bring beauty and joy and magic to the world.

I’ll conclude with another thing of beauty from Mr. Teller. When he was a young man, Mr. Teller came up with a trick he calls “Shadows.”

It really is a very graceful and simple piece that clearly means a lot to Mr. Teller. Like a poet who keeps a favorite poem in his or her reading rotation for years, Mr. Teller still performs “Shadows.”

You never know which of your works will endure the longest or will mean the most of you. The lesson, I suppose, is to throw yourself headlong into creating and improving and learning and hoping that something good will happen for you.

What Should We Steal?

- Respect your writing partners, colleagues and teachers more than you love them. Respect is hardier than love.

- Compose works that result in both heat and light. Think about all of the works that have survived the centuries…they all engage readers on a number of levels.

- Devote yourself to your work and to your discipline. Bear in mind that you belong to a long line of writers. Leave your own spin on the field, but honor the fraternity as well.

- Find the art in everything you do and make sure your life is a performance. There’s great beauty in extreme weather and mundane supermarket browsing.

If you found my analysis useful or enjoyed my writing style, would you consider checking out Great Writers Steal Press, where I have published some eBooks of the fiction and nonfiction variety? Just head over to books.greatwriterssteal.com, where reading is not homework!

Television Program, Uncategorized

1975, Penn & Teller

Title of Work and its Form: “ID,” short story

Author: Joyce Carol Oates (on Twitter @JoyceCarolOates)

Date of Work: 2010

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story made its debut in the March 29, 2010 issue of The New Yorker. The kind folks at that publication have been kind enough to offer the story online for your enjoyment. “ID” was subsequently chosen for Best American 2011 and can be found in that anthology.

Bonuses: Here is what blogger Karen Carlson thought of the story. Here is a cool review and discussion of the story over at Perpetual Folly. Here is a Wall Street Journal article about Ms. Oates and the touching way in which she dealt with losing her husband, one of the thousand natural shocks that flesh is heir to.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Perspective

Discussion:

You, kind reader, are witness to one of the worst days of Lisette Mulvey’s life. Thirteen-year-old Lisette had half of a beer before school; these things are easier when you have an absentee father and your mother often takes off for long stretches. The story chronicles a few hours in Lisette’s bad day, but Ms. Oates intertwines flashbacks and exposition with the dramatic present. We learn about Lisette’s crush on a boy and her mother’s poor behavior. Lysette’s mother works in the casinos of Atlantic City and seems to fit in with the seedier part of the AC culture. The officers (one male and one female) show Lisette a body in the morgue; the young woman doesn’t ID the body as her mother. The female officer tells her it’s all right; there are other ways to identify the woman who was found in a drainage ditch. The officers bring her to school, where Lisette tries to fall back into the comfort of her friends.

Ms. Oates is indisputably one of our American literary lionesses and has been at the top of her game for quite some time, with no end in sight. What is one of the million things that I love about her writing, and this story in particular? Ms. Oates produces work that is both of its time and timeless at the same time. In a way, she is like Alfred Hitchcock. No matter that Hitch was working with people from a different generation; he always produced films that felt immediate and spoke to anyone who saw them. Ms. Oates is the same way. You can tell that Ms. Oates has boundless curiosity because she knows how it feels to go to high school in 2010. She understands how a thirteen-year-old girl in 2010 feels about herself and her friends. As I get older and slightly wiser, I realize that I’m losing a little bit of this kind of knowledge. I haven’t gone trick-or-treating in more than twenty years. Could I really remember what it feels like? How to say this…romance has been a stranger for a while. Could I really depict young love with any fidelity? Ms. Oates would have no problem with these situations and emotions because of her deep understanding of humanity.

We’ve all heard that we should “write what we know.” Yes, that is good advice, but if we followed that advice with too much dedication, we would have no science fiction or horror or stories in which the nerdy guy gets the cheerleader. Ms. Oates points out in her author’s note that “ID” was inspired by the untimely death of her husband. A funeral director asked Ms. Oates to identify her husband’s body—she didn’t want to see it again. To my knowledge, Ms. Oates does not have first-hand experience of being a thirteen-year-old young woman tasked with identifying her dead mother. She does, however, KNOW what it is like to face the stark reality that the person you love is dead and to see their body in the morgue. We’re all human, right? It is more important to understand the emotional experiences that you are chronicling than to have first-hand experience on the topic. (Especially if you’re writing fiction, of course.)

When I was in high school, I wrote a lot of “high school” stories; I believe that’s perfectly natural. I certainly see a lot of “dorm stories” when my students turn in their work. (This tendency is perfectly natural, too.) We must remember that we have the license to write about anything we like. What fun would it be if we only write about people who are just like us who live lives just like ours? Boring!

Ms. Oates had a bit of a challenge in the story because she needed to get a lot of exposition into a story that is pretty much in real-time. As I pointed out, the exposition is woven in with the material that is in the dramatic present. Why aren’t these sections a bit of a roadblock? Why don’t they cause the reader’s attention to flag? Ms. Oates builds a ton of suspense into the story.

- Why do “they” want to see Lisette’s ID?

- “Some older guys had got her high on beer, for a joke.” Will Lisette’s drunkenness get her in trouble or complicate things?

- How will J.C. respond to the note that Lisette sent him? Will he break her heart?

- Mom doesn’t seem to be a very upstanding citizen. Complications?

- Uh oh. Two police officers want to see Lisette.

- Will the body turn out to be that of Lisette’s mother?

One reason the story is so very compelling is that the emotional and narrative foundation of the story is sprinkled in with grace and in such a way that Ms. Oates creates mysteries to which we want the answers! These “roadblocks” speed the reader along instead of holding them back.

What Should We Steal?

- Devote yourself to observing and trying to understand humanity. One of a writer’s primary duties is to reproduce the human experience on the page with as much fidelity as possible.

- Write what you know…within limits. If we followed this advice to the letter, we wouldn’t have any science fiction.

- Introduce “mysteries” into your work to make exposition all the more compelling. Your stories should introduce meaningful dilemmas anyway; use them to make your exposition even more of a treat to the reader.

Short Story

2010, ID, Joyce Carol Oates, Perspective, The New Yorker

Title of Work and its Form: “Interview by the Board, or, Barking up the Wrong Hydrant,” poem

Author: Heather Dubrow

Date of Work: 2013

Where the Work Can Be Found: The poem appears in the Spring 2013 issue of Asinine Poetry. You can find the poem here.

Bonuses: Here are the books that Ms. Dubrow has published, some of them scholarship and some of them creative writing. Here is an intelligent review of Ms. Dubrow’s book Forms and Hollows. If you have access to JSTOR through your library-aren’t libraries great?-you can read an essay about the Sonnets that Ms. Dubrow wrote for Shakespeare Quarterly.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Inspiration

Discussion:

This brief poem begins with a snippet from the New York Times. Apparently, co-op boards have now taken to interviewing pets before allowing their owners into the building. Ms. Dubrow then offers an example of what that interview might sound like.

Ms. Dubrow is a fascinating woman. I thought I recognized her name from somewhere when I read the poem and I must have stumbled upon her scholarship along the way. I adore people like Ms. Dubrow, who are full citizens of two important words; Ms. Dubrow helps us understand what literature means and creates it herself. I also foster not-so-secret desires to be an Elizabethan/Shakespeare/Early Modern scholar myself, in part because all of the people I know who are in the field are incredibly FUN and DEDICATED. Ms. Dubrow displays some of this playfulness in this poem. In a way, Ms. Dubrow is honoring writers such as Shakespeare and Jonson and Marlowe because she finds inspiration in the mundane things around her. Shakespeare didn’t have the Internet or newspapers as we know them, but he was always tossing in references to current events or celebrities or other writers. Ms. Dubrow found humor in an article from the Times and shared her flash of amusement with us. Were Shakespeare writing today, would he be sharing his wit on Twitter? (I’m curious as to what real scholars think.)

The questions and answers in Ms. Dubrow’s poem are offered in a sing-songy musical theater style. Compare these lines:

Q: In elevators are you subdued?

A: Those growling kids are much more rude.

To the lines from the Monorail song from that classic episode of The Simpsons:

Miss Hoover: I hear those things are awfully loud.

Lyle Lanley: It glides as softly as a cloud.

Apu: Is there a chance the track could bend?

Lyle Lanley: Not on your life, my Hindu friend.

Barney: What about us brain-dead slobs?

Lyle Lanley: You’ll all be given cushy jobs.

The lines of both examples are imbued with easy-to-detect meter and rhyme. This light-hearted approach is appropriate for both works. Conan O’Brien and the other Simpsons writers were trying to recreate the fun of musicals such as The Music Man. Ms. Dubrow offers us the fanciful image of a dog climbing into a chair and speaking to a co-op board. The poem is very short, so Ms. Dubrow didn’t bog the piece down with a complicated structure or form. (Not to mention the fact that it appears in a magazine called Asinine Poetry.) Ms. Dubrow’s approach to this piece is perfectly fitting-she invited us into the Times‘ world of “talking dogs” and left us quickly and with happy hearts.

What Should We Steal?

- Find inspiration in everything around you, not just the most explicitly poetic. There is humor and joy and sadness in the everyday, even if the object of your inspiration doesn’t really deserve a 2,000-word essay.

- Match the mete, rhyme and diction of your piece to its subject matter. A “silly” piece deserves to be examined in that same “silly” spirit.

Poem

2013, Asinine Poetry, Heather Dubrow, Inspiration

Title of Work and its Form: “Maximum Security,” short story

Author: Michael P. Kardos (on Twitter @michael_kardos)

Date of Work: 2008

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story debuted in the Winter 2008 issue of the Southern Review. “Maximum Security” appears in Mr. Kardos’s 2011 story collection, One Last Good Time. The folks at Press 53 are pretty cool. Why not buy the book from them? The story is also available through the EBSCO database. If you don’t know how those work, your local librarian will be more than pleased to show you.

Bonuses: Here is an interview Mr. Kardos did about his novel, The Three-Day Affair. Here are some very interesting blog posts Mr. Kardos made at The Missouri Review. Here is a short story Mr. Kardos placed with Blackbird in 2007.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Narrative Structure

Discussion:

What a great story. Brandon is the first person narrator, a young man who begins by telling the reader about his piano teacher, Rudyard Cross. The gentleman plays the organ and the music calms Brandon’s father, a man still getting over the death of his wife. Cross is also a little flamboyant. He enjoys life and does so with flair. When Brandon begins mimicking some of Cross’s mannerisms—as teenagers sometimes do—his father gets quite upset and cancels Brandon’s lessons. Brandon’s friend Danny joins in, pointing out that people are making fun of him for acting in a stereotypically homosexual manner. The bulk of the narrative recounts the time Brandon goes to a real, honest-to-goodness teenager party. He pays his three dollars for the keg and drinks a couple beers. Amanda Van Sickle kisses him without first obtaining permission to do so; the experience embarrasses and confuses him. The beer starts to get to Brandon and he loosens up a little around people he has never spent time with outside of school. He even steals some beer from a liquor store, which he drinks with some of the kids he thinks are “cool.” Brandon kisses Danny without first obtaining permission to do so and Danny punches him in the gut. Seeking solace, Brandon spends the night in the care of the parents whose house was used for the party. The next morning, Brandon is afraid of what his father will do to him; the story ends on a beautiful note, as Brandon disassociates and imagines safety and the last time he felt whole.

The first thing we must do is examine the structure Mr. Kardos employed for this story. “Maximum Security” features two parts:

- The background about Brandon and his father and their living situation, the information about Rudyard Cross. Brandon is picking up some mannerisms from Cross; his father and friends think he might be gay.

- The night of the party. Nonconsensual kisses, stealing beer and vomiting at a stranger’s house. The morning after, when Brandon is picked up.

We certainly need the first part to understand the second, but look at the number of pages each part occupies. The story occupies, give or take, 15 pages in the Southern Review. The story is split right down the middle; 7.5 pages for “part one” and 7.5 pages for “part two.” Mr. Kardos ensures that sufficient emphasis is placed on the night of the party; this is the dramatic present and this is the event that allows all of the issues of part one to interact, changing Brandon’s life. The story would not have the same impact if the party only lasted for three pages; Mr. Kardos plants the seeds and allows the flowers to blossom.

Mr. Kardos makes a very cool choice in the story. His narrator is somewhat sheltered. He didn’t have a curfew because it was unnecessary. Poor Brandon doesn’t have any “cool” friends and doesn’t hang out anywhere. When he gets in the car with Danny and two other boys, he is impressed by their jackets. Letterman jackets are a powerful symbol in high school, aren’t they? As a music-type nerd, I certainly didn’t have one. The guys who did had far better lives than me; they talked to girls…and the girls even talked back! Brandon is certainly in the same kind of boat. He’s a little “artsier” than most guys and isn’t successful at any of the endeavors that usually indicate social success. It’s perfectly natural that he would attribute some kind of power to the jackets.

Then Mr. Kardos does something beautiful. Brandon has stolen the beer and is trying to endear himself to people who aren’t quite in his social circle. Here’s Brandon making small talk:

We weren’t all friends, and nobody really knew what to say. At one point I asked Darius and Nick what sport they played, and they asked what I meant, and I said the jackets, and then they looked down at the ground, and Nick said trombone, and Darius said clarinet.

Mr. Kardos does two very important things with these two sentences. He depicts Brandon’s discomfort in making conversation and he subverts Brandon’s understanding of the characters. (In addition to the reader’s understanding of them.) EVERY teen feels as though they’re on the outside looking in. The people we think are having the best life ever usually aren’t. The beautiful and kind cheerleader has problems at home; the quarterback just lost his younger brother. (You’ve seen The Breakfast Club, right?) Mr. Kardos gracefully makes his minor characters very vivid, even in a fifteen-page short story.

Danny tells Brandon that his new mannerisms are making him sound “like a real fag” at school. Do many of us recoil from these unpleasant slurs? Of course. Should we use these words in a personal manner with people who may be offended by their use? Probably not. Writers and other creative people, however, are striving toward verisimilitude: the appearance of reality in fiction. In the time period in which Mr. Kardos’s story takes place, teenage boys used the word “fag” with each other. (And many, I’m guessing, still do.)

Imagine that Mr. Kardos had Danny say, “Why are you acting like such a young man who doesn’t conform to traditional gender representations in speech and behavior…not that there’s anything wrong with that?” The line would not ring true and wouldn’t mean anything. If you’re writing about Jackie Robinson, you must acknowledge that the despicable people didn’t heckle him with the term “African American.” The Phelps family and their Westboro Baptist Church don’t say that “Americans who happen to be homosexual” are responsible for natural disasters. I am sure that other folks will disagree, but I believe that it is disrespectful to your audience to pull punches. Mr. Kardos respects his reader; he knows they understand that HE is not saying something horrible. His character uses the naughty term. Mr. Kardos has faith that his reader will get that the story is pro-gay and anti-jerk. Further, if you turn a “naughty” word into an asterisk salad, you’re doing a disservice to the “victim” you’re trying to protect.

Several months ago, I tuned into NPR—I think it was Diane Rehm—to hear a discussion about the pernicious “A word.” Unfortunately, I was a few moments late; I never found out which “A word” they were talking about. I love NPR, but they were treating me like a child that day.

What Should We Steal?

- Count the number of pages you devote to different sections in your work and devote the appropriate page space to each. The most important parts of your work deserve the most page space.

- Employ powerful details to fill out your supporting characters. Just one or two details can go a long way, particularly if they are the right ones.

- Use unpleasant words in the correct manner. Your reader will understand your intent and the experience will be one of mutual respect.

Short Story

2008, Maximum Security, Michael Kardos, Narrative Structure, Ohio State

Title of Work and its Form: “Give Them What They Want,” short story

Author: Richard Lakin (on Twitter @Lakinwords)

Date of Work: 2013

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story appears in Issue 5 of The Puffin Review. You can find the story here.

Bonuses: Here is Mr. Lakin’s story, “The Debt He Carried,” first published in Notes From the Underground. Here is a cool travel piece Mr. Lakin wrote for the Telegraph.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Callbacks

Discussion:

Mr. Lakin keeps this story short and sweet. The story begins as Derek picks up a prostitute in a neighborhood that has seemingly had an outbreak of such behavior. His wife Jane is on his mind as Carla gets into the car. He drives away, pointing out the envelope full of money in the glove compartment. Carla is a little worried for a while; Derek is driving her pretty far and, as I understand it, women in her line of work don’t like to go very far with their customers. At last, we have the reveal. Derek stops the car in the beautiful countryside and tells Carla to check the boot. (That’s the trunk of the car, for all of us Americans.) Derek has not taken Carla out to the country to harm her. No, he wishes to make her the subject of one of his works of art.

Mr. Lakin does a lot of wise things in this story. Perhaps the most important choice he made was to make his first-person narrator an artist, the kind of man who can use some beautiful turns of phrase. We expect an artist to notice the small details that Derek releases, including the hue of Carla’s hair and the “apple-shaped smudge” of a bruise on her calf. Of course, it can work the other way around; a writer will choose phrasing and details according to the character’s proclivities.

If you’ve ever seen a comedy routine-standup or improv-you’ll see what are called “callbacks.” These are running themes or recurring images whose meaning may change throughout the work. When Derek is negotiating with Carla, he asks how long she has been working as a hooker. She replies, “Well, you’re not the first. Is that going to be a problem?” She is offering the truth in a forthright manner and trying to put a dignified face on her work while continuing to give the client what she thinks he wants.

The ending line of the story is the same. Carla sees the…art stuff in the trunk and understands he just wants to draw her. When Derek says the line, the situation is reversed. He is playfully reminding her of the time a few minutes earlier when they were strangers and she thought that he wanted to have sex with her. (And perhaps to violate the terms under which he wears his wedding ring.) The line means something different at the story’s conclusion and reflects upon the middle of the story, too. This is one of the great uses of a callback. Repeating the line reminds us that the story is about art and opening yourself up to others and evokes all of the different ways in which this can be done. (In an artistic manner, a sexual manner, a gastronomic manner…)

What Should We Steal?

- Employ a narrator who can realistically release the details you want to provide to the reader. Artists will generally think like artists. They’ll notice visual details. Different narrators will prioritize different ideas.

- Allow callbacks to lend significance to events that happen earlier in your work. Prudent repetition allows you to change and to deepen the meaning of your work as a whole.

Short Story

2013, Callbacks, Richard Lakin, The Puffin Review

Title of Work and its Form: “My Father with Cigarette Twelve Years Before the Nazis Could Break His Heart,” poem

Author: Philip Levine

Date of Work: 1994

Where the Work Can Be Found: The poem debuted in The Forward and has subsequently been anthologized and reprinted. The poem concludes Mr. Levine’s 1994 poem collection, The Simple Truth, a book that won the 1995 Pulitzer Prize. You can also find the poem in This Is My Best: Great Writers Share Their Favorite Work, a book edited by Retha Powers and Kathy Kiernan. Mr. Levine also contributed a brief essay in which he describes the creation of the poem.

Bonuses: Here is an interview Mr. Levine gave to The Paris Review. Here is an NPR interview in which Mr. Levine discusses his upbringing and poetry. Here is the Library of Congress page dedicated to Mr. Levine, a Poet Laureate Emeritus.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Inspiration

Discussion:

Mr. Levine and I have a lot in common. We were both born in the Detroit area and we both write poetry. Unfortunately, that’s about the extent of it. Mr. Levine chose to conclude his book with this poem and his entry in This Is My Best reinforces that the poem means a great deal to him. As well it should; the poem’s first person narrator begins the work by evoking an ancient memory, his father “commanding” a kitchen match to flame with his thumbnail and talking about important things. The narrator “fast-forwards” sixty years to the present, putting the old memories into context. Mr. Levine (and the narrator) were children when Hitler was coming to power; the poem presents a slice of what the world was like before it changed and before Mr. Levine developed his powerful critical faculties.

I love the way Mr. Levine opens the poem:

I remember the room in which he held

a kitchen match and with his thumbnail

commanded it to flame

The image explicitly communicates that the poem is a story and implies that the tone will be a a quiet, contemplative one instead of a more intense one. The match itself is a kind of campfire, right? How many life lessons have been shared by parents under such conditions? The beginning of the flame, the beginning of the Lucky Strike moment: these are subconscious cues to the reader that he or she is about to get the same kind of important lesson as the narrator receives.

Before I read Mr. Levine’s essay in This Is My Best, I thought that the title of the poem sounded like the title of a work of visual art. (I swear! I even wrote “TITLE LIKE A WORK OF ART” in the margin.) In that short essay, Mr. Levine describes his reluctant visit to a museum, whereupon he was struck by a painting: “My Father with Cigarette,” by Harry Lieberman. Mr. Levine was inspired for a number of reasons. The story of Mr. Lieberman’s father bore some resemblance to that of his own, for example. The poem, Mr. Levine points out, came out of him relatively quickly and easily and he simply augmented the title of the painting. Why not follow Mr. Levine’s example? If you look at some visual art, you’re going to be provoked into having some cool ideas. Art can be a very potent launching point for writers.

Even better, no two writers will get the same idea or feeling from the same work. Look up Eugene Delacroix’s “Orphan Girl at the Cemetery.”

What kind of stories or images occur to you when you look at her?

What Should We Steal?

- Begin a didactic work with an image of convocation. People are trained to understand when a LESSON is about to begin. Baseball games begin with the National Anthem, court proceedings begin with a standing ovation for the judge.

- Flip through a book or art or visit a gallery and steal away. If your mind is open, you’re probably going to get some ideas worth jotting down.

- TITLE FORMULA #5550199: Borrow the title of a great work of art or modify it to fit your needs.

Poem

1994, Inspiration, Philip Levine, Poet Laureate, The Simple Truth