Title of Work and its Form: Fort Starlight, novel

Author: Claudia Zuluaga

Date of Work: 2013

Where the Work Can Be Found: The book was released by Engine Books in September 2013 and can be found in all fine independent bookstores, including [words] Bookstore in Maplewood, New Jersey. Wow; the folks at [words] put together a lot of cool programming. (You can also follow them on Twitter.) Why not consider purchasing the book directly from the cool people at Engine Books?

Bonuses: Check out this short story Ms. Zuluaga placed with the excellent Narrative Magazine. If you had any doubts as to whether or not you should pick up Fort Starlight, take a look at this Publisher’s Weekly review. Ms. Zuluaga also put together a playlist for Largehearted Boy that accompanies the book quite nicely.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Narrative Structure

Discussion:

Ida Overdorff is not exactly in a good place in her life. She’s in her mid-twenties, but she doesn’t have very much figured out. She loves baking and has a friend or two in New York City, but the specter of her unpleasant childhood has held her back from finding the community she seems to crave. Fort Starlight is the story of how Ida finds her community and her place in the world. The book begins as Ida arrives in Florida, expecting to pick up a check after selling a small patch of land she bought several years earlier as a teenager. Ida takes a look at the land while it is still hers; a small and dilapidated house is located on the lot. Eventually, she decides to make that house her temporary home. Ms. Zuluaga gracefully folds in a number of other characters, all of whom eventually become a part of Ida’s extended family. Ryan and Lloyd are a gay couple who offer her friendship. Eccentric Peter sells her a cheap bike. The manager of the local supermarket hires her to serve as the store’s bakery manager; some of the customers become a part of her life. Even poor Mitchell Healy, a twelve-year-old boy who begins the book dead and face-down in the river, ends up influencing Ida. Through the course of Fort Starlight, Ida gets a lot closer to being the person she wishes to be.

I spend a lot of time thinking about the structure of fiction, so I was most impressed by the way Ms. Zuluaga put her book together. Fort Starlight operates according to a series of countdowns, the function of which is to assure the reader that a satisfying end is in sight. The first countdown is the wait for the check that Ida is to receive from the land developer. Once she gets the check, of course, she can move on with her life! After that, Ida must wait for the check to clear. Once the check clears, of course, she can move on with her life! There are, of course, complications in Ida’s story and the goalpost she’s aiming for in life is pulled back several times. Even though Ida (and the reader) must reset the countdown from time to time, we are happy because we soon realize that Ms. Zuluaga is not really resetting anything. Fort Starlight is THE STORY OF THE TIME IDA SPENDS IN FLORIDA LEARNING WHO SHE WANTS TO BE AND HOW SHE OVERCOME THE PROBLEMS OF HER PAST.

Fort Starlight is a far different kind of story, but consider this idea with relation to a film we all know. What are the “countdowns” in The Wizard of Oz?

- Dorothy wishes to escape her sepia world and that mean woman who is always snarling at her. Once that happens, she’ll be a happy person!

- Dorothy must follow the yellow brick road in order to get to the Emerald City, where The Wizard can help her get back home. Then she’ll be happy, right?

- Dorothy must assemble a team of friends to help her along the way. Friends are always good, aren’t they?

- Dorothy must thwart the attacks of the Wicked Witch and defeat the flying monkeys. Once she does that, then she’ll be happy…won’t she?

- Dorothy must accept that The Wizard is just a regular person and find a way back home…then everything will be good, won’t it?

These are the smaller countdowns and plotlines in The Wizard of Oz. There is, however, an overarching deadline in the film, just as there is one in Fort Starlight:

THE WIZARD OF OZ TELLS THE STORY OF THE MANNER BY WHICH DOROTHY REALIZED THAT SHE ALREADY HAS EVERYTHING SHE NEEDS IN LIFE.

Ms. Zuluaga also does something interesting with the way she builds the family around Ida. The book begins very small. We see two blackbirds flying around Florida and a man who wishes to build a development there. (You know…a community. Of people. Who protect and care for each other. Just the kind of thing Ida needs.) Then the third person narrator immerses us in Ida’s consciousness. Ida is, after all, the anchor (the Dorothy Gale) of the story. Eventually, the chapters open up, introducing characters whose connection to Ida is not yet established. The craft is easily apparent here; Ms. Zuluaga has successfully taken seemingly disparate stories and has woven them together like a tapestry. Another image came to mind as I read the book. Ida is a baker and Ms. Zuluaga is doing what a baker does: folding a number of different ingredients together until they make a cohesive whole:

When Ida bakes, she must consider the tartness of the fruit to determine how much sugar to fold into her batter. Ms. Zuluaga needed to balance the characters in something of the same way. Ida, for example, is pretty shy and sheltered, but Ryan and Lloyd are pretty outgoing; the combination helps Ida and the narrative to progress.

Now take a look at the opening of Chapter Two:

This is the section in which Ms. Zuluaga introduces one of the many powerful metaphors in the book. In the first paragraph, the author reminds us of the tarp that covers some of the dilapidated home’s exterior. The wind, sometimes a powerful force in Florida, sucks the tarp in and out. Okay. That’s basic description. Then look at the third paragraph. The expansion of the contraction of the tarp is made into something new and beautiful. Ms. Zuluaga makes the house a living thing. The blue tarp is a diaphragm that pulls life into the home. (Including Ida and those she later befriends.)

What’s the lesson here? I love the way that the description begins as a bare description, but is turned into a much more complicated metaphor. Why does the idea have such impact? One reason is that Ms. Zuluaga introduces the breathing home so gracefully. Once we know the basic fact (there is a tarp on the outside of the home), we’re much more willing to take a fanciful leap. We must prepare our audience to understand our potent metaphors and do so without drawing undue and flashy attention to them.

What Should We Steal?

- Build your story according to countdowns large and small. You don’t necessarily need to literally put a ticking time bomb in your story, but keep in mind that all stories can be broken down into some kind of countdown. The film Die Hard is THE STORY OF THE DAY THAT JOHN MCCLANE KILLED ALL OF THE BAD GUYS IN THE NAKATOMI TOWER AND REGAINED THE LOVE OF HIS FAMILY.

- Fold characters and storylines together like a baker making scone batter. Match sweet characters with sour. Broad storylines with quiet character moments.

- Prepare your audience for your prettier and more complicated metaphors. It’s one thing for Babe Ruth to hit a home run in the World Series. We understand the impact and we almost expect it to happen. When Babe Ruth prepared the audience by calling his shot (if he did so), he turned a simple home run into a much bigger statement about himself and the game.

Novel

2013, Claudia Zuluaga, Engine Books, Narrative Structure, The Wizard of Oz

Title of Work and its Form: The short films hosted on wafflepwn’s YouTube channel

Author: wafflepwn

Date of Work: 2009 - present

Where the Work Can Be Found: The films can be found on the wafflepwn YouTube channel.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Structure

Discussion:

It all started with concerned parents who shut off the World of Warcraft account when their son, Stephen, needed to be disciplined. Stephen did not take the punishment with very much grace:

Nor did Stephen appreciate the car his parents gave him for his sixteenth birthday:

And Stephen certainly did not endure the pain of his first tattoo with much grace:

Over the course of two dozen videos, Stephen has demonstrated his lack of impulse control, his adolescent sexual confusion and his inability to understand the effect his behavior has on others. Why are these videos something more than simple digital artifacts of sibling rivalry? The creators (ostensibly Stephen and his brother Jack) have actually constructed effective short films that trade on classic themes.

First, let’s look at the structure. Jack is very good at releasing the exposition the audience needs and he does so in a graceful manner. Here’s an example. Jack begins “Greatest freak out ever 4” by staring into the camera and stating,

Okay, my parents aren’t home and Stephen’s playing my Dad’s guitar, so I’m going to mess with him a little, okay?

This is all the setup we need. What are the compelling points of drama involved in the film?

- Sibling rivalry. Even if you don’t have a brother or sister, you understand that siblings enjoy messing with each other.

- Your parents’ stuff. You didn’t mess with your parents’ stuff, did you? Probably not. And especially not a guitar, something that can be expensive to replace.

- The adolescent interest in playing guitar. This is where garage bands come from. Young people enjoy making music…and playing guitar is a traditional way to facilitate conversations with prospective boyfriends or girlfriends.

So Jack tells Stephen he sucks, knowing that Stephen will scream and yell and eventually do something stupid. Jack and Stephen are big fans of Freytag’s Pyramid, even if they don’t know it. Stephen’s rage gets bigger and bigger until he finally destroys his father’s guitar Pete Townshend-style. There’s even a fitting denouement: Stephen walks away, having demonstrated his manhood and unwillingness to endure teasing from his brother.

In case you’ve forgotten, here is Freytag’s Pyramid:

Freytag would also smile upon “How the Stephen Stole Christmas:”

Jack releases the exposition: he has hidden all of Stephen’s presents on Christmas morning. If you know Stephen, you know this will not end well. There are peaks. Stephen opens the present Jack got him. Stephen realizes there are no presents for him under the tree. There’s TENSION…how will Stephen react? Through the course of seven minutes and thirty-nine seconds, Jack and Stephen fulfill all of the obligations of story, including characterization, a beginning, middle and end, a climax and a resolution. Even though the young gentlemen are making “silly” YouTube videos, they are still telling stories in the time-honored traditions that have worked since the dawn of man.

I am often asked how long a story or a play should be. I often suspect that the person asking the question is hoping for a cut-and-dried answer, that I will tell them, for example, that their ten-page play must be ten pages long. No more and no less. Unfortunately, the real answer is both simpler and more complicated:

A story must be as long as it demands and deserves.

I know. That sounds like a zen koan or something, doesn’t it? There are plenty of beautiful and perfect two-page stories. There are just as many beautiful and perfect 800-page novels. What makes the difference? Some plots are more complicated and require more page space for the author to accomplish his or her desired effect. The wafflepwn plots are very simple:

- “Stephen cleans up the kitchen.”

- “Stephen gets a visit from the police when he breaks my Mom’s TV.”

- “Stephen learns how to swim.”

These are not wildly grand ideas. Les Miserables needed to be incredibly long, but you can tell the story of how Stephen reacts when he sees a cat in less than two minutes. Yes, you can consider all of the wafflepwn videos collectively and end up with a whole with more meaning than its parts. But Jack and Stephen never let a bit go on too long. In this way, they remind me of Holland/Dozier/Holland and Smokey Robinson and all of the other great Motown songwriters. Those writers got your toe tapping, gave you a thrill and then ended the song. No down time. No digressions. Beginning, middle, end and out. Can you honestly tell me there is any down time in a song such as “ABC?”

What Should We Steal?

- Adhere to traditional story structure, even if you’re working in a non-traditional medium. The methods by which stories are told change over time. The nature of the most effective stories do not.

- Make your story as long or as short as it needs to be. I’m not happy about it either, but word count guidelines only apply to what editors want to read. They shouldn’t affect the length of your story in the least. (They just determine where you send your work.)

Feature Film

2009, Greatest Freakout Ever, Motown, NOOOOOOOO!, Stephen, Tosh.0, wafflepwn

Title of Work and its Form: “Going Down on Polypropylene,” creative nonfiction

Author: Alicia Catt

Date of Work: 2013

Where the Work Can Be Found: The piece can be found in Volume 2, Issue 9 of Pithead Chapel, a fine online journal. Go check it out.

Bonuses: Here is another work of creative nonfiction that Ms. Catt placed in The Citron Review. Here is a piece from decomP Magazine about trichotillomania. And another piece from Mary: A Journal of New Writing.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Point of View

Discussion:

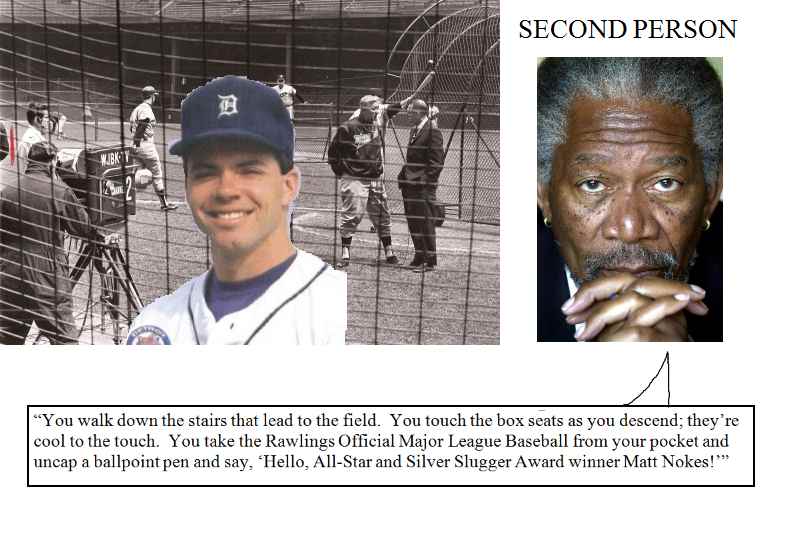

At the age of twelve, Ms. Catt was devoted to the environment and lived in perpetual fear of what the other people would say about her. Were any of us at our best at twelve? Ms. Catt was a little overweight and was uninformed and confused about sex. Based upon that last description, I might have thought this piece was about me. But there’s another reason: the piece is in second person. You meet a woman who doesn’t quite belong in small-town Wisconsin who knows a lot about sex. You blush when she simulates a sexual act with a pudding cup. You are sad that Carrie gets abused, but you are glad that her presence pushed you onto a higher rung of the social ladder. Carrie is gone before long and you suffer one more indignity; the soda cans you picked up during a field trip contained ants that crawl around on you during the bus ride back to school. Ah, adolescence.

So the first thing that I noticed about the story was the point of view. The piece has been classified as nonfiction, so I was a bit surprised to see that Ms. Catt employed the second person. After all, this is ostensibly HER story and the events described (pretty much) really happened. (Depending, of course, how much Ms. Catt agrees with Pam Houston’s thoughts regarding truth in nonfiction.) What does Ms. Catt gain by taking HER story and putting it onto YOU?

- Novelty. There are second-person memoirs out there, but you don’t see these kinds of works every day. Readers can be compelled by aberrations from the norm, so Ms. Catt earns attention from her first sentence. (It becomes her responsibility, of course, to keep that attention and does so with some beautiful sentences and turns of phrase.)

- The reader is aligned with the author. As I’ve pointed out, the second person reduces distance between the narrator and writer; Morgan Freeman is not only talking to you, but he’s telling your story! Here’s the graphic I made using my hype MS Paint skyllz:

- The reader has an easier time remembering his or her own adolescence. It’s been a long time since I was a teenager and I’ve blocked out a lot of the feelings and events I don’t want to remember. Ms. Catt cuts through that defense mechanism with sentences such as, “But you’re made of oddity.” Once Ms. Catt puts you in a mental state in which you can remember how you felt as a teenager, her own awkwardness and longing become more potent.

One of the facets of prose that has been a challenge in my own writing is figuring out how best to cast my scenes. When I was younger, I was often tempted to have my third person narrators go overboard with their DIALOGUE AND DESCRIPTION OF SMALL EVENTS. In that way, I was failing to make use of the fiction writer’s toolbox. In a play or screenplay, a writer has no narrator (you know what I mean) and can really only make use of dialogue and action. Fiction writers can make use of a narrator who simply tells the reader what they need to know and fast-forwards when they need to.

There are no SCENES in “Going Down on Polypropylene,” though there is plenty of scene work. Consider this scene from Ms. Catt’s piece:

You beg your mother for rides to Econofoods, and burrow through the grocer’s dumpster to recycle every scrap of corrugated cardboard they’ve mistaken for waste. Even when you cut your fingers on sticky, dark things, you keep digging and sorting. You dig and you sort until your mother’s had enough and drags you home.

See how boring that scene would be if it were written as a real scene?

Alicia stood before the grocer’s dumpster, plastic bags on her hands in a futile attempt to prevent her from touching the slimy garbage. She loved the environment, but the aroma of hot, wet garbage made her sick.

Alicia’s mother was inside and would be done shopping soon. Alicia had to be quick. She opened up the clear recycling bag and started grabbing for cardboard. Sharp edges nipped at her fingers…

See? Boring. And not just because I wrote it. Ms. Catt makes the felicitous choice to tell us enough to imagine the scene without getting bogged down in the boring and unnecessary.

What Should We Steal?

- Select an unexpected point of view. Why not a second person memoir? Why not tell the story of a historical event from a first person point of view?

- Allow your narrator to describe scenes instead of writing them as scenes. In prose, the narrator can zip through time, reach into the minds of others and work all kinds of other magic. Take advantage of these superpowers!

Poem

2013, Alicia Catt, Pithead Chapel, Point of View, Second Person, trichotillomania

Title of Work and its Form: The Ancestor’s Tale, nonfiction

Author: Richard Dawkins (on Twitter @RichardDawkins)

Date of Work: 2004

Where the Work Can Be Found: The tome can be found in all fine bookstores. You can also order it online.

Bonuses: Dr. Dawkins has presented many television programs about science and skepticism. They’re definitely worth a long look. Dr. Dawkins formalized the concept of the “meme,” although the use of the term has changed somewhat. Take a look at the powerful concept he described. Dr. Dawkins joined Daniel Dennett, Christopher Hitchens and Sam Harris in a discussion that came to be called “The Four Horsemen.” These four powerful thinkers offer insight into religion (and the lack thereof) and into the development of human culture. If you are into skepticism, you may also enjoy my essay about Michael Shermer’s Why People Believe Weird Things, which also links to my essay about Hitchens.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Narrative Structure

Discussion:

The Ancestor’s Tale is a book with a modest conceit. All Dr. Dawkins did (with some help from research assistant Yan Wong) is to work backwards step by step to tell the complete story of the evolution of all of the organisms in the history of the Earth. He begins by describing humans (and protohumans) and slips in graceful descriptions of the minor genetic variances between us and how they came to be. Then he tells the “tales” of bonobos and eventually hippos and salamanders and flounders, all the way back to plants and bacteria. Dr. Dawkins crams the history of life on Earth into 600 pages and does so in a manner that just about anyone can understand.

Beginning a massive project can be daunting. Turning a two-inch stack of blank pages into a novel? What a frightening prospect! Condensing your whole life story into a coherent 300 pages? Seemingly impossible! How did Dr. Dawkins confront such a massive undertaking and end up with such a satisfying product?

First of all, he divided his grand conceit into digestible pieces. No book could literally detail the evolution and contain anecdotes about every single species that has ever evolved. Instead, Dr. Dawkins chose to write about a few dozen of the most important and representative branches of the tree of life. The book seems easier to write if you think of it in this manner:

Okay, I’ll write a ten-page essay about the fruit fly because of its fascinating genetics. I have about eight pages worth of interesting information about the cichlid. I should also write about 2500 words about the hippopotamus. Oh, and I can’t forget that beautiful chimera, the duckbill platypus.

Dr. Dawkins also clearly acknowledges that he stands on the shoulders of giants. Not only is he working in concert with the countless scientists who have contributed to the field of biology over the past few thousand years, but he is also very clear about the sources he consulted during composition of The Ancestor’s Tale. Yes, citing things is important in order to avoid plagiarism. More importantly, Dr. Dawkins affirms himself as one of the storytellers documenting the development of life on Earth. And the book does indeed tell a story. Instead of being a dry, purely scientific tome, Dr. Dawkins uses details of the life of Queen Victoria to reinforce his point about the manner in which geneticists can use family trees to trace faulty genes, such as the one that causes hemophilia. Dr. Dawkins drops a quote from Rudyard Kipling to help demonstrate how we know that Vikings conquered local populations in more ways than one. Dr. Dawkins even makes use of the Judeo-Christian Bible, not as a scientific reference, but as a culturally ingrained metaphor that aids the reader in understanding. No matter what you’re writing, bear in mind that you are in someway telling your reader a story and are bound by a storyteller’s obligations.

If you read any of Dr. Dawkins’s books, you can’t help but notice his enthusiasm. In other hands, the tale of how the star-nosed mole perceives the world could be a boring one. Not when Dr. Dawkins is at the helm. Whether or not you agree with his (lack of) religious belief, you must at least acknowledge that Dr. Dawkins is passionate about his cause. Take a look at the TED talk in which he tries his mightiest to rouse nonbelievers from their slumber and urges them to make themselves heard:

Dr. Dawkins certainly has little patience for creationism being taught in schools as science, but his innate curiosity inspires him to engage with those who feel otherwise.

At times, some folks may accuse Dr. Dawkins of being “offensive” or “confrontational.” In some way, they are correct. Dr. Dawkins, like the rest of us, enters the free marketplace of ideas and does his best to demonstrate why his are more powerful than those of others. He has spent decades contributing to his fields of interest, not merely acting as an interested onlooker who attempts to shape what he didn’t help to build. Where do Dr. Dawkins’s critics go wrong? The man without trying to tear others down undeservedly. When a creationist insists the Earth is 6,000 years old, Dr. Dawkins does his best to refute the argument with professional calm. The ideas in his books and those he expresses in his other outreach efforts are sometimes complicated. Critics may be paralyzed by confirmation bias. Others may construct a straw man, knowingly or unknowingly distorting Dr. Dawkins’s work through simplification.

What happens when someone disagrees with Dr. Dawkins? They get an impassioned reply that may result in some discomfort or a moment of awkwardness. Why, here’s an example:

If you disagree with Dr. Dawkins, he is not going to let the air out of your tires. He is not going to tell the world that you’re cheating on your husband or wife. (Especially if it’s not true.) He certainly won’t do his best to convince your employer that you need to be fired for some transgression, real or imagined.

No, Dr. Dawkins conducts himself in the manner to which we should aspire: he surrounds himself with ideas and uses reason as his primary intellectual weapon.

What Should We Steal?

- Imagine your massive or complicated work broken down into manageable pieces. Writing a fifteen-hour opera seems like a terribly difficult task…consider writing one aria at a time until you see the larger work take shape.

- Remember that you are telling a story, no matter what you’re writing. The narrative may be somewhat buried in that instruction manual you’re writing for Black & Decker’s new blender, but you’re still TELLING THE STORY as to how the user can make margaritas or wine slushies to keep his or her guests happy.

- Conduct yourself with passion in all of your endeavors. There is more to you than the stack of work that you produce. If, for example, you are lucky enough to a writer who receives interview requests, consider them an opportunity, not an unpleasant obligation.

Nonfiction

2004, Christopher Hitchens, Narrative Structure, Richard Dawkins, Skepticism

Title of Work and its Form: “The Cassandra Complex,” poem

Author: Megan Peak

Date of Work: 2013

Where the Work Can Be Found: The poem debuted in THE BOILER. You can read the poem here.

Bonuses: Read and listen to another poem by Ms. Peak that was published in The Bakery. Here‘s a poem that was published in Thrush Poetry Journal. And another poem that was published in Diagram.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Authorial Intent

Discussion:

This poem quickly establishes its first person narrator, a man or woman who describes what seems to be a complicated and often unpleasant romantic relationship. I’ll elaborate further in the essay, but this poem seems particularly open to interpretation-a very good thing. Me? I’m thinking the narrator is in love with a partner who is literally or figuratively abusive. The “swollen lake” around the “ring of my eye,” the “warning signs/ on the tips of your fingers.” Does the final stanza indicate that the partner has returned after an absence and that the narrator has reached some kind of catharsis with respect to the situation.

Now, I don’t happen to know Ms. Peak, but she seems like a very cool person. I have no idea what she was thinking when she wrote “The Cassandra Complex,” but you can see how thoughtful and well-crafted the poem is; she certainly had SOME big ideas swimming in her head. People who have been writing for a long time definitely understand that, upon publication, a work belongs to the world in some way. Readers are going to interpret and discuss your work and you may not always agree with the interpretation. You have to be okay with that. Writer Corey Ann Doyle kicked off a bit of a to-do in 2012 when she involved herself in some Internet drama surrounding Emily Giffin, NYT-bestselling writer. Fans of Ms. Giffin did not like Ms. Doyle’s negative (but fair) review of one of her books, so they descended upon Ms. Doyle like the Wicked Witch’s flying monkeys. Ms. Giffin and her husband even involved themselves in the drama.

Here’s the bottom line: your work is not going to be received with 100% love and people are going to have interpretations of your work that differ from your own. Maybe Ms. Peak wrote this poem about a weeping willow tree in the back yard of her childhood home. That interpretation of the poem is fine. And my interpretation is equally valid. When I talk with students about a poem such as Poe’s “Annabel Lee,” they sometimes want to stop their analysis after they find out about Poe’s sad history with women. “Why, his wife died of tuberculosis. Anabelle Lee must have died of tuberculosis. He must have been thinking of her when he wrote the poem.” This may well be the case, but Mr. Poe gave us the right to decide for ourselves when he published his poem. It could be about his wife. It could be about a capsized boat. It could be a description of what he saw in an opium-fueled nightmare. Who knows? Your ideas about the poems are just as valid as those of Poe. (Especially so if you have evidence from the text to support your claim.)

Ms. Peak hits us with a big concept right off the bat. Don’t know what The Cassandra Complex is? Here’s what Wikipedia says:

The term originates in Greek mythology. Cassandra was a daughter of Priam, the King of Troy. Struck by her beauty, Apollo provided her with the gift of prophecy, but when Cassandra refused Apollo’s romantic advances, he placed a curse ensuring that nobody would believe her warnings. Cassandra was left with the knowledge of future events, but could neither alter these events nor convince others of the validity of her predictions.

The metaphor has been applied in a variety of contexts such as psychology, environmentalism, politics, science, cinema, the corporate world, and in philosophy, and has been in circulation since at least 1949 when French philosopher Gaston Bachelard coined the term ‘Cassandra Complex’ to refer to a belief that things could be known in advance.

Remember…we never stop our research with Wikipedia, but the site offers a good overview. The title seems to indicate that the protagonist has offered several warnings in the past…all ignored. (Perhaps this concept is what primed me to think about domestic violence.) What else does Ms. Peak earn with the title she chose? A connection to concepts and ideas that have been around for thousands of years. Go ahead and write that poem about Kim Kardashian’s behind. The odds, however, are not very good that the poem will be on the lips of readers in 2525. (If man is still alive…still alive.)

Much of this essay is about all of the BIG IDEAS that Ms. Peak’s poem brought to mind: a compliment in itself. I certainly don’t want to fail to point out what I loved most about the poem. Look at how beautifully she plays with language in “The Cassandra Complex.” The poem’s stanzas are of irregular length and there doesn’t seem to be a regular rhyme scheme or meter that can easily be charted. (The meter is there, to be sure, but it’s not as easy to discern as the meter in a limerick, for example.)

Let’s take a detailed look at the poem’s first stanza:

The neck of me glows hard, glares

long. Wreaths of hot breath shudder

each curve of your signature

down the length of my spine.

“The neck of me” is an odd phrase, isn’t it? Ms. Peak must be using it on purpose. What does the phrase accomplish? We learn that the poem is in first person. The phrase also seems a little bit passive, doesn’t it? So we can guess that the character may be somewhat reticent to discuss what the poem is about; it must be something “difficult” or “embarrassing.”

Look at the two GL sounds in the first line. Don’t those two sounds seem powerful in the poem? You read them aloud, right? You can really punch those sounds; a contrast with all of the S sounds that follow.

And look at that image. (Ms. Peak has a number of powerful images in the poem.) The signature down the length of the spine…the other character has, essentially, taken possession of the narrator in some way, right? Isn’t that what it means when you write your name on something?

It’s hard for me to quantify, but the way that Ms. Peak uses language in the poem just FEELS good. It feels as though she’s in control and the lines SOUND like poetry. If I could tell you exactly what I mean…why, then I would be as good a poet as Ms. Peak!

What Should We Steal?

- Understand that your reader’s interpretation of your work may vary wildly from your own…and that’s okay. Writers are like parents who send their children off to college. We’ve done all we can to make our babies the best they can be, but the world will evaluate them as it will.

- Entwine your work with those of great thinkers. We still talk about concepts given us by the Greeks because the ideas are complicated and powerful and true. Oedipus’s swollen foot still treads the boards because the play and ideas are still provocative. Five years from now, people will have forgotten about the Miley Cyrus VMA performance that pushed the poison gas attack in Syria off of the front page of CNN.

- Include “odd” phrases that somehow seem perfect in retrospect. Every writer who has written about baseball has described the “crack of the bat.” What new phrase can you use that will also FEEL right?

Poem

2013, Authorial Intent, Megan Peak, Ohio State, THE BOILER

Title of Work and its Form: “After the Gazebo,” short story

Author: Jen Knox (on Twitter @JenKnox2)

Date of Work: 2013

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story debuted in issue 2 of ARDOR Literary Magazine. You can read the issue for free right here.

Bonuses: Here is an excellent The Smoking Poet interview with Ms. Knox in which she talks about what it’s like to share very personal writing with a crowd. Why not spend a little time at Ms. Knox’s Amazon page? Here is a short story Ms. Knox published in Monkeybicycle, a very cool online journal.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Narrative Continuity

Discussion:

He and she had a beautiful life. They were joggers who met in a park and subsequently fell in love. They adopted a pug with dermatitis and planned a small but beautiful wedding. Then fate intervened. I don’t want to discuss the last page yet; here’s your last chance to read the very short story.

You know what? This story is not actually about the man and woman. Sure, they’re the ones who get married and they’re the ones who get into a car accident. But Ms. Knox’s story is, in a way, about the pug the couple adopts. Look at the second and third paragraphs…they’re all about the pug. Prince, as the dog comes to be called, goes for walks with the couple. Prince wears a bow tie at the wedding. Prince, at the end of the story, spends his time wondering where his real owners are. The love story (and death) of this man and wife are examined through Prince’s lens.

One reason this was a good idea is because it may be odd to continue a story after the death of the focal character or characters. Think of The Wizard of Oz. The whole story is told from Dorothy’s perspective. Had she died in the middle of the story, the audience may have had trouble adjusting to a completely new narrator or protagonist. The dog provides continuity that would otherwise be erased. George Lucas uses the same technique in the Star Wars movies.

R2-D2 and C-3PO are not really protagonists in the films. They’re great tangential characters, but Han Solo and Luke Skywalker and Princess Leia and Darth Vader are much more central to the overall plot. But there they are; R2-D2 and C-3PO are always around; Lucas uses the characters to provide continuity. Vader dies…Luke will die at some point…but those robots will always be around to tell the story of the rise and fall of Anakin Skywalker. Just like Prince the pug, R2-D2 and C-3PO will be welcomed into new families in the future and may never love anyone as much as they do Luke and Han and Chewie.

Ms. Knox also makes use of one of the great advantages possessed by those who write fiction. Your narrator can, at any time, zoom ahead in a story. Some folks (including myself) feel a need to explain far more than is necessary. Look what Ms. Knox’s narrator does with the beginnings of these paragraphs. Instead of accounting for every moment in the lives of the couple, she simply zooms along and offers the necessary information…all the while holding the reader’s hand.

They took the pug to the dog park Saturday mornings. A month passed and they were still not sure about a name.

They enjoyed taking Prince on lazy walks after work.

She gained five pounds. He gained ten. They joined a gym a few months before the wedding.

The day of the wedding, they awoke five hours and twenty minutes before they had to be at the meeting center by the gazebo.

Ms. Knox wastes no time; the narrator asserts firm control over the reader’s experience. Such control is necessary in this kind of story. The plot itself isn’t very complicated. Instead, Ms. Knox seems to have been trying to evoke emotion over the sad state in which Prince finds himself. The author likely knew the story wouldn’t be very long and employed a justifiably controlling narrator who could match the length of the story to the nature of the plot.

What Should We Steal?

- Establish continuity by examining your doomed protagonists from the perspective of another character. Long after everyone else in Star Wars is dead, C-3PO and R2-D2 will be roaming the galaxy, the story of the saga in their heads.

- Empower your narrator to be particularly controlling. Friend, you have a story to tell and you need to hire the narrator who will get that story to your audience in the most efficient and appropriate way possible.

Some stories need a John Moschitta:

Others need a Gunnery Sergeant Hartman:

Still other stories need a calm and kind narrator:

Which does your work demand?

Short Story

2013, ARDOR Literary Magazine, Jen Knox, Narrative Continuity

Title of Work and its Form: “Corn Maze,” creative nonfiction

Author: Pam Houston (on Twitter @pam_houston)

Date of Work: 2012

Where the Work Can Be Found: The piece is a part of Metawritings: Toward a Theory of Nonfiction, a Jill Talbot-edited volume. The kind folks at Hunger Mountain have also made the piece available on their web site.

Bonuses: Here is an interview Ms. Houston gave to Montana Public Radio in which she discusses some of the issues brought up in “Corn Maze.” Here is an interview Ms. Houston granted to The Rumpus. You can find a lot of Ms. Houston’s short-form work at Byliner.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Truth

Discussion:

“Corn Maze” is a lyric essay in which Ms. Houston combines several small stories that allow her to examine what “truth” really means in writing. She discusses her alcoholic parents and how it affected her childhood, she recounts experiences she had with editors and fact checkers and describes the process that resulted in her book Contents May Have Shifted.

Ms. Houston’s essay confronts a very important issue in the field of nonfiction: the slippery nature of truth. What is TRUE when you describe your personal history? After all, your memory may be faulty. Individuals inherently interpret different events in different ways. Is the writer’s duty to describe objective reality-as inefficient as a strict reading of reality may be-or to use his or her skills to create a fiction that creates the same feeling he or she had in the moment?

Ms. Houston advocates the latter policy. While I write creative nonfiction on occasion, I’m much more of a fiction guy. When I’m writing a short story or working on the latest novel that will never be published, I am truly grateful for the ability to make up ANYTHING I want. Any song can come on the radio at any time, leading a character to reconsider his or her life. I love that I don’t have to try and REMEMBER anything about a character other than what I’ve already written about them. If I think my protagonist should have a big nose…boom. He or she does.

Nonfiction is different, of course. When I write explicitly about my “interesting” childhood, I think a lot more about what DID happen, as opposed to what COULD happen in the piece. The past several years have been an interesting time for nonfiction writers; as nonfiction becomes even more “creative,” many readers have rejected the notion of playing fast and loose with the truth of the interesting situations that sold books and increased Internet traffic. We all remember Oprah’s confrontation with James Frey, whose A Million Little Pieces was revealed to contain a number of important fabrications.

A couple years later, a Holocaust memoir by Herman Rosenblat was found to contain scenes that simply could not have happened. Writing for Salon, Lev Raphael points out that so many smart people (editors, a ghostwriter) were duped, at least in part, by their desire for a sad injustice to have some kind of happy ending.

JT LeRoy earned acclaim for the gritty writing he produced about his prostitute/drug addict past…until it was discovered that JT was really a woman named Laura Albert.

Pam Houston describes how she inserted characters into her travel pieces and even changed the weather she experienced, sometimes at her editor’s request. Here’s part of her defense:

But if you think about it, the fact that I did not really have a flirty exchange with three Italian kayakers doesn’t make it any less likely that you might. I might even go so far as to argue that you would be more likely to have such an exchange because of my (non-existent) kayakers, first because they charmed you into going to the Ardèche to begin with, and second, because if you happened to be floating along on a rainless day in your kayak and a sexy, curly-haired guy glided by and splashed water on you, you would now be much more likely to splash him back.

Ms. Houston seems to be urging writers to do two things:

- Question the nature of reality and truth. Physical and emotional realities sometimes contradict each other. Everyone has different memories of the same situations. Even language itself can muddy several interpretations of the same event.

- Strive to write pieces that will communicate the true feeling you’re going for, even if it means bending the truth a little bit.

One of the great strengths of a lyric essay is the seeming randomness of each short section. When the reader makes their way through the sections of a lyric essay, he or she is making intentional and unintentional connections between them. This technique is a kind of impressionism, I think. If you look at a painting by Renoir from a distance, you see what appears to be a blurry photograph, I suppose. Check out “Bal du moulin de la Galette.” Renoir is trying to capture the feeling of a…moulin in a…Galette. (Forgive me, I took German.)

Look at an extreme close-up of the canvas:

Renoir combined independent smears to create the illusion of reality. The same technique is at play in this lyric essay. How do details about corn relate to the author’s alcoholic parents or her own fabrication of the details of her travels? It’s up to you, dear reader. This “randomness” is part of the charm of the lyric essay. Like an impressionist painter, the author is inviting you even more explicitly to make use of your conscious and subconscious.

What Should We Steal?

- Contemplate the real nature of truth. Everyone has a different definition and you must serve the one that makes the most sense to you.

- Combine disparate elements to create a unified whole. The sections of a lyric essay are like breadcrumbs; where will they lead your reader?

Creative Nonfiction

2012, Hunger Mountain, Pam Houston, Truth

Title of Work and its Form: “Teach For America in the Terrordome,” creative nonfiction

Author: Heather Kirn Lanier (on Twitter @heatherklanier)

Date of Work: 2012

Where the Work Can Be Found: Ms. Lanier published an excerpt from her book Teaching in the Terrordome in Utne Reader. The piece can be found here. If you don’t already have the book, perhaps you would like to purchase the tome from Amazon or a local independent bookstore.

Bonuses: Here is an interview Ms. Lanier granted to the Baltimore Sun. Ms. Lanier is also an excellent poet. You can find links to many of her poems here. Ms. Lanier published a heartrending piece in Salon that you will enjoy.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Dialogue

Discussion:

“Never drive west of MLK.” The piece begins with several warnings offered to the author as to how she can remain safe in West Baltimore. Ms. Lanier was about to begin her tenure as an instructor in the Teach for America program; she hoped to “level the playing field” for economically disadvantaged students. In this excerpt (part of the first chapter of the book), Ms. Lanier describes her initial feelings about the school in which she taught and the colleagues already on staff. The piece concludes with her interview with an administrator who inadvertently informs Ms. Lanier what her time in the Terrordome will be like.

Ms. Lanier’s writing is special because her prose manages to be poetic and compelling while maintaining clarity. Her skill allows her to break the conventional rules of prose without confusing the reader. Look what she does with the description of the “character” of Ms. Brown, the administrator whose unconventional interview begins Ms. Lanier’s teaching career:

Ms. Brown nodded. “You know,” she said, “Baltimore has an excellent transportation system. You needn’t always rely, on the car as a vehicle.” The syllables of Ms. Brown’s words were meticulously modulated and well-pronounced, and she paused mid-sentence as though she were dictating. “Have any of you, taken the bus? From time to time, a person might make use, of the Baltimore Bus System, which runs reliably, between all areas of the city.” She seemed to take great pains to avoid the ums and ahs of everyday speech. There was something unnaturally perfect about it.

The first time I read the piece, my eye got hung up on that oddly placed comma. For that brief instant, I wondered whether that bit of punctuation was a simple mistake. The following sentence, of course, offers a perfectly appropriate explanation for why Ms. Lanier made her “mistake.” You can’t break TOO many rules, or prose breaks down into a meaningless balderdash of words. On the other hand, slipping that comma into odd places allows the reader to hear Ms. Brown’s voice in his or her head.

What are some other ways to use prose to affect the sound of a character’s voice?

- Capitalize words that he or she EMPHASIZES.

- Employ run-on sentences to reinforce that a character may be boring or confusing.

- Use ellipses…to indicate if a character has…William Shatner voice.

Here’s another example of the interesting relationship between the look of prose and the sound that the words should create in your head. Who can forget the “sorority girl e-mail?” If you haven’t heard of this amazing piece of pop culture flotsam, here’s Pophangover’s summary: “One of the executive board members of [a] Sorority emailed out an expletive-ridden letter to the entire chapter, bitching out the sorority sisters because of their BORING and AWKWARD behavior during Greek Week.” Actress Alison Haislip did a reading of the e-mail that will curdle your blood. Focus on Ms. Haislip’s reading of the letter at around 1:40.

Now look at the text of the original:

First of all, you SHOULDN’T be post gaming at other frats, I don’t give a FUCK if your boyfriend is in it, if your brother is in it, or if your entire family is in that frat. YOU DON’T GO. YOU. DON’T. GO. And you ESPECIALLY do fucking NOT convince other girls to leave with you.

The woman who wrote the original e-mail has employed many of the techniques that I pointed out. “YOU” and “DON’T” and “GO” are typically not sentences…but wouldn’t you agree that they ARE sentences in this case? The author broke the rules and created a very strong tone, certainly strong enough to guide Ms. Haislip’s performance of the monologue.

I think that detail occupies an interesting place in creative nonfiction, particularly when compared with fiction. In a short story, the writer relies upon the reader to fill in detail in some way. Yes, a fiction writer must provide specifics, but the world that the story occupies is partly the reader’s creation. Can a writer describe every car on the road? Should a writer describe the dress of every character to make an appearance? Probably not. When it comes to creative nonfiction, however, the author is explicitly trying to distill reality out of experience instead of creating reality out of imagination.

The first page or so of the excerpt focuses upon Ms. Lanier’s drive into West Baltimore. (This technique is a shrewd move in itself; the author has established the setting immediately, and has done so through the eyes of a “fish out of water.”) Early on, Ms. Lanier writes:

At a traffic light at North Warwick, an old black man crosses in front of me. With his back bent forward, he makes shaky, pained steps across the road. I smile when I read his stretched out, threadbare T-shirt. Walk to Win, it says.

Now, this is not the essay in which I discuss how much fabrication people think should be allowed in creative writing. (That’s coming up soon.) So I’m going to take the description at face value. I love that the old man’s shirt says, “Walk to Win” and I love that Ms. Lanier has remembered such a small and interesting detail. Inclusion of this bit of detail makes the man more than just set dressing. Yes, the man is elderly and has a little trouble crossing the street. Perhaps the gentleman is wearing the shirt as a reminder to himself. Perhaps he wishes to inform others that his infirmity is not a dire setback in his life. Who knows? But the fact that Ms. Lanier includes the detail allows us to speculate and makes the world of the story (a real world in this case) appear much more vibrant.

What Should We Steal?

- Mold your sentences to reflect the sound of the character’s voice. People are unique not just for the words they say, but how they say them.

- Allow minor details to accomplish major work. While you can’t go crazy with detail, do remember that small personal choices can have a big impact on a reader’s perception of a character.

Creative Nonfiction

2012, Baltimore, Dialogue, Heather Kirn Lanier, Terrordome, Utne Reader

After I told you, dear reader, what we can steal from poet Allison Davis, she was kind enough to mention that she had an essay on craft that she wanted to share. Ms. Davis asked if I might want to share the piece with the GWS audience. Great Writers Steal is quite pleased to present this essay, also downloadable in PDF format for sharing with students or writing groups.

How to (and How Not to) Steal: Writing About Animals

Allison Davis

“It’s too late to raise the soul,

some ossified conceit we use to talk about deer

as if we were deer…”

Ira Sadoff, “The Soul”

“Lest anybody spy the blood And ‘you’re hurt’ exclaim!”

Emily Dickinson, “A Wounded Deer—leaps highest”

“Birds. Figure out what they symbolize, and then get them out of the poem.”

Claudia Emerson, in workshop

In my poem “Summer Contours,” a speaker looks out across his suburban neighborhood at night. He hears crickets chirping (technical term: stridulating) and looks up what they are saying. He crudely summarizes their four calls—the calling song, the courting song, the copulatory song, and the warning song—as “come to me, stay, fuck me, fuck off.” This superimposition of human communication onto animal communication is problematic: humans can’t speak for animals and our experiences aren’t interchangeable. While I researched cricket communication, it is still illogical for my speaker to put words into the crickets’ mouths—I mean, wings. At worst, the speaker exploits the crickets as a vehicle to discuss his own relationship problems—the crickets’ value depends on their human utility. At best, the speaker attempts to connect with the crickets as a lonely person may seek acceptance from a stranger at a bar. Navigating the line between these two extremes—exploitation and connection—is difficult, especially as animals can’t let us know when we’ve crossed that line.

It is easy to accidentally exploit, eroticize, or simplify what we cannot understand, to mistake silence as negative space waiting for colonization. Poems about silent, motionless road kill, for example, often present dead animals as conceits rather than victims. There are so many poems about road kill that I no longer question why poetry is the road less traveled—apparently there are deer all over the place. The speaker in Carol Frost’s “To Kill a Deer” shoots the aforementioned deer and “counted her last breaths like a song/of dying and found her dying./I shot her again because her lungs rattled like castanets.” When the car of the drunken teenager in Jon Loomis’ “Deer Hit” collides with a deer, the driver lifts the carcass “like a bride.” In Mark Wunderlich’s “Difficult Body,” the speaker remembers the deer hit by his father as “the body of St. Francis in the Arizona desert.” And in the granddaddy of all roadkill poems, William Stafford’s “Traveling through the Dark,” the speaker spots the ubiquitous dead deer and, wanting to prevent another accident, flatly notes that “It is usually best to roll them into the canyon.”

Where to draw the line between relating to and learning from the environment and exploiting it for sentiment? In all of these dead deer poems, the death of a deer is used as a “safe,” distanced way to meditate upon human mortality. The deer is the prop, not the point.

Yet I admire all of the poets whose work I cited above, and poetry certainly doesn’t have to be ethical nor a speaker likable. Many canonical poems feature animals, such as “Ode To A Nightingale,” “The Raven,” “The Panther,” “The Windhover,” and the poem that made me start writing poetry, “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird.” Animals are inspiring, and it’s psychologically understandable why poets displace emotions, especially complex ones, onto another specie. But heavy poems need to carry their own weight: to use an animal’s suffering as a convenient, dramatic background for a poem about human suffering is lazy. Romanticism that is at the expense of a suffering thing isn’t romantic—it’s exploitative. I always run dead animal poems through the dead human test— unless I’m dealing with absurdist poetry, it doesn’t captivate me to read “I shot the dead baby again because her lungs rattled like castanets” or “It is usually best to roll dead babies into the canyon.” Maybe I’m not a romantic, but if you hit me with your car, even if you’re a very talented poet, don’t lift me like a bride—call for help.

When writing poetry about animals, I analyze the animal’s purpose. Is the animal literal or metaphorical? Is the poem realistic or surreal? Do I need to research this animal? Am I treating animals with at least the respect that I would give to a person? If I am addressing an animal that cannot speak, am I really just addressing a human audience? If so, can I stop hiding behind the animal and approach my actual subject?

Gretchen Primack directly addresses the relationship between animals and poetry in her collection Kind, such as in her poem “Big Pig.” The collection considers the dangers of human projection and presents animals as living subjects, not metaphors. Her book makes not only an ethical argument but an aesthetic one: if poetry is going to differentiate itself in a print culture full of gratuitous sentiment, assumption, and tabloid, then poets must have enough skill to respect subjects as much as we use them. Speaking about the work of Objectivist poet Charles Reznikoff, Harvey Shapiro notes “In the precision of his lines, people and objects maintain their own lives. This is a moral point, and Reznikoff is a moral poet.” I would argue that being moral perhaps was a result of being precise—if we acknowledge that we don’t know at least as much as we do—that we write precisely because the world still surprises and moves us—then perhaps there is little difference between writing well and ethically.

ALLISON DAVIS’s poems have appeared or are forthcoming in The New Republic, Prick of the Spindle, and Speak Peace: American Voices Respond to Vietnamese Children’s Paintings. She is a graduate of the Vilnius Yiddish Institute Summer Program. Her chapbook Poppy Seeds was published by Kent State University Press as part of the Wick Poetry Chapbook Series.

Poem

Allison Davis, Emily Dickinson, GWS Essay, Ohio State, Poetry

Title of Work and its Form: “Someone Ought to Tell Her There’s Nowhere to Go,” short story

Author: Danielle Evans (on Twitter @daniellevalore)

Date of Work: 2009

Where the Work Can Be Found: The short story made its debut in Issue 9 of A Public Space, one of the top literary journals around. It was subsequently selected by Richard Russo and Heidi Pitlor for Best American Short Stories 2010 and can be found in that anthology.

Bonuses: Here is an interview Ms. Evans did with PEN. Here is a profile of the author from the Washington Post. Here is what writer Karen Carlson thought of the story.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Juxtaposition

Discussion:

Georgie is a soldier in love with Lanae, a woman he’s known since he was a child. Unfortunately, their romance is star-crossed. As the first line makes clear,

Georgie knew before he left that Lanae would be fucking Kenny by the time he got back to Virginia.

Georgie is indeed back from his service in the Middle East and Lanae is indeed living with Kenny, who is the manager of a KFC. Georgie seems to have a little PTSD and has trouble getting his own life going, so he assumes the role of babysitter for Lanae’s kid, Esther. Caring for Esther also addresses Georgie’s other big internal conflict: the death and pain he saw visited upon children in theater. Georgie takes Esther to one of those little kid boutique stores and invites the kid to enter a contest for tickets to a concert held by Hannah Montana-esque singer. Esther pretends (kinda believes?) that Georgie is her father and wins the contest with her video about how glad she is that her Daddy is home from war. She wins the contest, of course. Then the press discovers the lie; Georgie is labeled a monster by the press and Lanae shuts him out of whatever quasi-family they created.

I really liked this story a great deal. One of the biggest reasons is that Ms. Evans played with an unexpected conflict. The first couple pages describe Georgie’s deepl affection for Lanae, a woman he’s known just about his whole life. I was excited for the inevitable fight (physical or otherwise) between the Army Man and the Chicken Man. Instead, Ms. Evans took the story in a far more interesting direction by focusing on the relationship between Georgie, Esther and the two girls he remembers from Iraq. (Certainly not a romantic love triangle, but a triangle nonetheless.) Men fight over women all the time, but entering a contest for High School Musical tickets under a “fraudulent” pretense is going to get you some big-time attention. A lesser writer (myself, for example), might have spent twenty pages on Georgie’s resentment of Kenny, but Ms. Evans spends that time on a much more interesting relationship between the living and the dead.

Ms. Evans also does a fascinating job of putting Georgie into two similar situations whose differences illuminate the man’s character:

- Iraq: Georgie’s job is to protect civilians, especially little girls. He gives them candy and tries to calm them and inspire hope in them in some way. He acts as a kind of father to these sometimes fatherless children.

- Home: Georgie’s job is to care for Esther, a little girl. He gives her presents and treats and tries to be a positive force in her life. He acts as a kind of father to a young woman who doesn’t have one.

This juxtaposition creates some sad subtext. Georgie always tries to do the right thing and tries to help people, but he ends up failing, no matter what. How will your characters react when you pluck them from their current situation and force them to deal with similar stressors in a different setting?

What Should We Steal?

- Play with the unexpected conflicts between your characters. We’ve all read (and written) stories about two men fighting over a woman. Instead, make this tension latent in favor of a different conflict related to the characters.

- Shuttle your character between similar situations to illuminate his or her character. What will your creations reveal when they face two different situations that have a lot of similar qualities?

Short Story

2009, A Public Space, Best American 2010, Danielle Evans, Juxtaposition