What Can We Steal From Elizabeth Tallent’s “The Wilderness”?

Title of Work and its Form: “The Wilderness,” short story

Author: Elizabeth Tallent

Date of Work: 2012

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story was first published in Spring 2012’s Issue 129 of Threepenny Review one of the top journals out there. Elizabeth Strout (and Heidi Pitlor) chose the story for the 2013 edition of Best American Short Stories and it can be found in the anthology.

Bonus: Here is what Karen Carlson thought of the story. Here is “Little X,” a piece of memoir that Ms. Tallent published in Threepenny Review. Here is Ms. Tallent’s page at Powell’s Books.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Narrative Compensation

Discussion:

The third-person protagonist of the story is an English professor who is endlessly fascinated by her students’ preoccupation with machines. The young people are seemingly addicted to the bleeps and bloops that make it clear that the devices are alive. The professor was enthralled by a different object as a child: a mummy that helped her understand death and the meaning of history. The strongest bit of narrative relates to this struggle between history and inanimate objects: Wal-Mart wants to plow over the woods of The Wilderness to build a new story. The narrator’s great-great-grandfather nearly became a casualty of war on that ground. The story ends as the narrator reconsiders what it means to elude death and to live life. (It was also my impression that Ms. Tallent makes the case for literature in the story; Shakespeare’s body was not immortal, but he’s still with us and will be until the final human breathes his or her last.)

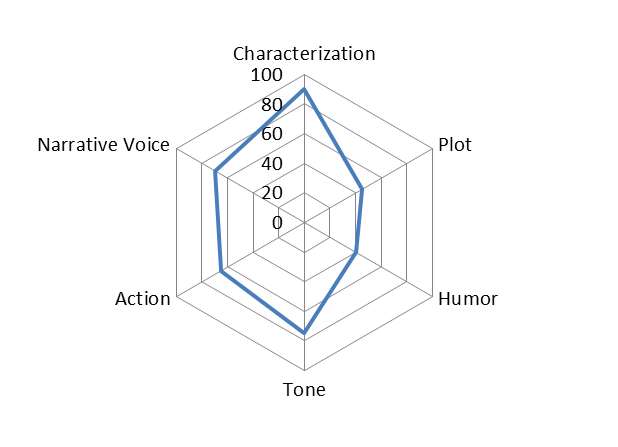

We can all certainly agree that “The Wilderness” is not a white-knuckle barnburner with a complicated plot. We’ll also agree that plot is an important part of a story. So why aren’t we upset with Ms. Tallent? It’s easy: she makes more potent use of the other tools in the writer’s toolbox in order to compensate. We all love the eerie inevitability of the plot of “The Lottery,” for example. Stuff is always happening in that story; people file into the town square, slips are drawn from the box, and men, women and children pick up stones. The narrative thread of “The Wilderness” is not as strong as that of “The Lottery” and that’s perfectly fine because Ms. Tallent offers extremely potent characterization to help us understand the professor. Ms. Jackson’s sentences in “The Lottery” have a beauty about them, but the sentences must, by necessity, take a backseat to the plot. Unbound by a similar obligation, Ms. Tallent offers us sentences that are a joy unto themselves.

Here’s a chart I made for a previous essay that illustrates my point. (I would love to believe that every GWS reader has gone through every essay, but I know it’s not the case.) A story is like a spider web or a net. A web or a net can have odd dimensions and it can even have holes, so long as the other parts of the structure are strong enough to hold it together. The plot of “The Wilderness” may not, as Nigel Tufnel might say, go to eleven. Other facets of the story, however, DO go to eleven (which is one louder), ensuring that the story is coherent and enjoyable.

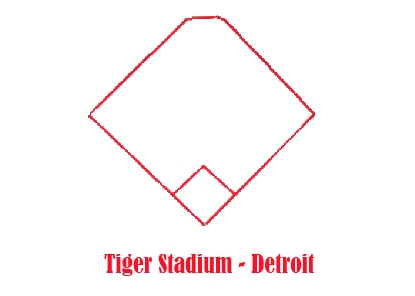

Let’s think of it another way. Spring Training is going on as I write this. (My beloved Tigers are trying to figure out what they are going to do at short.) Until 1999, the Tigers played baseball at the corner of Michigan and Trumbull, filling the stands of the most beautiful ballpark ever. Look at the dimensions of Tiger Stadium:

Let’s think of it another way. Spring Training is going on as I write this. (My beloved Tigers are trying to figure out what they are going to do at short.) Until 1999, the Tigers played baseball at the corner of Michigan and Trumbull, filling the stands of the most beautiful ballpark ever. Look at the dimensions of Tiger Stadium:

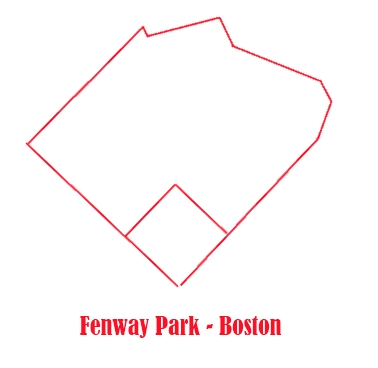

See how even? See how beautiful? Now THAT’S an outfield. Baseball is a rare sport whose playing field isn’t completely regulated by the rules. Yes, the bases must be ninety feet apart, but the shape and dimensions of the outfield vary wildly between ballparks. Think about Fenway Park. The builders had a bit of a problem: the street running along left field was very close to home plate. See:

See how even? See how beautiful? Now THAT’S an outfield. Baseball is a rare sport whose playing field isn’t completely regulated by the rules. Yes, the bases must be ninety feet apart, but the shape and dimensions of the outfield vary wildly between ballparks. Think about Fenway Park. The builders had a bit of a problem: the street running along left field was very close to home plate. See:

How did the builders compensate? Why, they made the left field fence extremely high. (It’s that “Green Monster” you’ve heard so much about.) If that fence were five feet high, each Red Sox home game would have a score of 23-22.

How did the builders compensate? Why, they made the left field fence extremely high. (It’s that “Green Monster” you’ve heard so much about.) If that fence were five feet high, each Red Sox home game would have a score of 23-22.

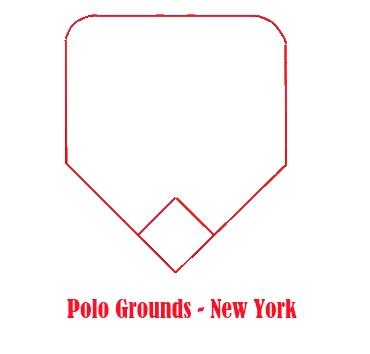

Check out the dimensions of the Polo Grounds, the former home of the New York Giants (and briefly the Yankees and Mets).

No, you’re not seeing things. You’re seeing why they called it the “polo grounds.” Each foul pole was really close to home plate, so the fences were higher. The Giants also compensated for those generous porches in right and left by making center field a vast wasteland where home runs go to die. (Or to turn into doubles.)

No, you’re not seeing things. You’re seeing why they called it the “polo grounds.” Each foul pole was really close to home plate, so the fences were higher. The Giants also compensated for those generous porches in right and left by making center field a vast wasteland where home runs go to die. (Or to turn into doubles.)

Wasn’t that a fun and unexpected way to consider my point? When one facet of our work is, by design, a little weak, we must compensate by adjusting the prominence of the other facets. Would Alfred Hitchcock have chosen “The Wilderness” as the basis for his next suspense film? Probably not. He would, however, have admired the story’s depth of characterization and its philosophical underpinnings.

Another facet of “The Wilderness” that I admire is the way that Ms. Tallent encouraged me to think about BIG ISSUES in a graceful manner. She made her character think about them first. “She” doesn’t seem to have liked her former colleague very much, but his flirtatious question has had her thinking ever since he asked what she would want on her tombstone. Now, Ms. Tallent is not forcing us to think too much. That would be a violation of the writer’s First Duty. (It’s the writer’s job to do all of the work so the reader can have all of the fun.) Ms. Tallent is, however, inviting us to think big thoughts. Invitations are fine; dictates are not.

Have you ever been asked, for example, which three books you would take with you to a desert island? Which family member would be the first you rescue from a burning building? These are difficult questions to answer when you’re put on the spot. Instead, Ms. Tallent simply offers up the question for her character; we can choose whether or not we want to address it.

What Should We Steal?

- Boost the power of other parts of your work when another part is a little weak. Okay, so you’re writing Transformers 8: The Planet of the Machines. Each of the characters are named “Guy” and “Girl” because the characters in the Transformers movies are irrelevant. There better be some pulse-pounding action scenes in the script to make up for it.

- Ensure that any deep thought on the part of the reader is voluntary and earned. I think about the nature of humanity and our responsibilities to each other when I read Les Miserables. I probably wouldn’t do so if Victor Hugo did something like this:

2012, Best American 2013, Elizabeth Tallent, Narrative Compensation, Threepenny Review

Leave a Reply