What Can We Steal From Tim Seibles’s “Sotto Voce: Othello, Unplugged”?

Title of Work and its Form: “Sotto Voce: Othello, Unplugged,” poem

Author: Tim Seibles

Date of Work: 2012

Where the Work Can Be Found: The poem made its debut in the Fall/Winter 2012 issue of Alaska Quarterly Review, a journal so consistently good that you’re not even angry when they reject you. Denise Duhamel and David Lehman selected the poem for The Best American Poetry 2013.

Bonuses: Mr. Seibles is a highly accomplished poet; why not consider purchasing one (or another) of his books from your local independent bookstore? Here is an interview Mr. Seibles gave while serving as the 2010 Poet-in-Residence at Bucknell University.

Mr. Seibles gave this wonderful TEDx talk about poetry:

Element of Craft We’re Stealing:

Discussion:

Through the course of eleven stanzas, Mr. Seibles offers us a glimpse into the mind of one of Shakespeare’s most intriguing tragic heroes. Othello is ostensibly explaining himself to Iago, but the “brave Moor” is confessing to himself, working through his own guilt in the context of the self-understanding he has gained through the course of the play.

The first thing to mention is that Mr. Seibles engaged in the tried-and-true act of simply playing in the sandbox of another writer. (The Bard of Avon has been dead for nearly 400 years, so there’s certainly no possible ethical conflict.) I love how the poem does double duty. One on hand, it’s a creative work about a deep character whose thoughts help us understand our own. On the other hand, it’s a work of literary criticism. Mr. Seibles offers his interpretation of Othello and his motivations by putting words into his mouth. (Just like Shakespeare did!)

There are so many fantastic opportunities for this kind of poem.

- We certainly got Medea’s thoughts…what was Jason really thinking about her actions?

- Aren’t you curious as to what Liza-Lu (Tess of the D’Urberville’s daughter) thinks about her mother when she has her own child?

- What does Mephastophilis/Mephostophilis say to the NEXT guy?

Mr. Seibles offers us some excellent insight in the note he included with his bio in Best American Poetry. He says,

I wanted the stanza variations to be the visual equivalent of the players: Othello alone, he and Desdemona, the couple, and, of course, the poison triumvirate.

If you re-read the poem with that concept in mind, the conceit seems even cooler. The stanzas have the following number of lines:

1, 2, 3, 1, 2, 3, 2, 1, 2, 1, 1

While the “reliable pattern” breaks down, Mr. Seibles’s concept remains cool and appropriate. Look at the last two stanzas…can’t we all agree that Othello is “alone?” I love what Mr. Seibles did with the stanzas because he is writing in service of his primary duty. Now, Shakespeare wrote in far more definite (and restrictive) forms. The lines of verse were in iambic pentameter. The sonnets had fourteen lines (three quatrains and a couplet). Even though Mr. Seibles fails to follow the rules of any established form, he is careful to make sure that the poem does indeed follow its own internal logic. The number of lines per stanza correlates to the perspective from which it is emerging.

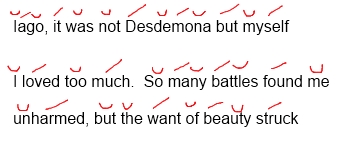

While the lines are not iambic, they still have that kind of iambic pentameter feel:

(You’ll also note that the second line should count as iambic pentameter, not withstanding that final foot.)

(You’ll also note that the second line should count as iambic pentameter, not withstanding that final foot.)

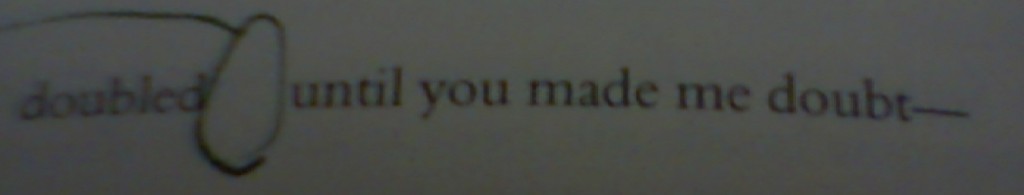

Mr. Seibles also points out another way in which he fits the form of the poem to the conceit that inspired him. Check out the eighth stanza:

Yes, I used my fountain pen to mark the space between the first and second words. (And yes, I took the picture with the camera on my cheap media player because it’s all I have.) This extra space is a representation of Mr. Seibles’s desire to let the lines “breathe as we might imagine sad Othello did.” So Mr. Seibles violates the “rules” of composition, but does so for the most beautiful and important reason: in the service of the emotion he wanted to communicate and the story he wanted to tell.

What Should We Steal?

- Put your own stamp on the literary legacy of a classic. Public domain works are just that…they belong to all of us. What do you think the Wicked Witch of the West’s early years were like? (Shoot. That one has already been done.)

- Ensure that your piece follows some kind of form, even if that form is specific to that work alone. All creative works must adhere to internal logic. Citizen Kane is one of the best films ever made, even though it follows its own rules, not those of the conventional three-act structure.

2012, Alaska Quarterly Review, Denise Duhamel, Desdemona, I Never Gave Him Token, Tim Seibles, William Shakespeare

Leave a Reply