Title of Work and its Form: Forest of Fortune, novel

Author: Jim Ruland (on Twitter @JimVermin)

Date of Work: 2014

Where the Work Can Be Found: Tyrus Books is responsible for publishing the book; why not buy a copy directly from them? Independent bookstores would also appreciate your business. The book is also available from Powell’s and Amazon.

Bonuses: You should definitely check out the site that Mr. Ruland put together for his book. Here is Mr. Ruland’s blog. If you can get over your jealousy, take a look at some of the work Mr. Ruland has published in The Believer.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Narrative Structure

Discussion:

Forest of Fortune is a novel that defies easy categorization and does so in the best of ways. The book is certainly “literary,” for whatever that means. Mr. Ruland has also packed in elements of the supernatural thriller; the titular casino game, for instance, seemed to echo the evil games of chance in the Twilight Zone episodes “The Fever” and “Nick of Time.” The book also confronts a vast canvas; it’s not just the story of three people who have a location in common. Taken as a whole, Forest of Fortune is a somewhat sprawling depiction of a place that is at once sad and joyful, a place where the hopeless cater to the hopeful and most visitors don’t notice the irony that they have traveled to the middle of nowhere to surround themselves with bright, flashing lights and contrived excitement. Whether or not he did it consciously, Mr. Ruland seems to be influenced by the climax and denouement of Poe’s “The Fall of the House of Usher.”

Okay, that’s the fancy-pants way to describe the book. Here’s the way we look at the book if we’re thinking in terms of structural engineering. Forest of Fortune entwines the stories of three people who have a close relationship with Thunderclap Casino, an Indian gaming establishment in a fairly remote part of southern California. (Note: I use the term “Indian gaming” because that seems to be the industry’s preferred nomenclature.)

Here are the third-person protagonists employed by the author:

- Alice - She’s an employee at the casino and is in a precarious position in her life. This change manifests itself in her frequent department shifts and her challenging roommate situation. Even worse, her epileptic seizures seem to be both symptom and cause of her problems.

- Pemberton - The gentleman was a “hard-partying copywriter” in L.A. until his fianceé booted him for excessive drinking, a DUI and her all-around dissatisfaction. He begins the book by interviewing for a position in Thunderclap’s marketing division.

- Lupita - Well, she’s a gambling addict and perhaps an alcoholic. Her sister Mariana has her life together…and Lupita has a close relationship with levers, reels and flashing lights.

…Aaaaand Mr. Ruland throws us a bit of a curveball. The first page of prose is in italicized first-person. This perspective should remain a little bit of a conundrum. It suffices to say that Mr. Ruland shrouds this voice in acceptable mystery and fulfills his obligation to clarify what is going on as the book goes on.

What’s the next thing we do when considering a novel? That’s right. We look at the structure. Mr. Ruland’s doldrums-trapped characters are given several seasons to change:

|

Section Title |

Pages |

| Winter | 7-86 (80 pages) |

| Spring | 87-184 (98 pages) |

| Summer | 185-238 (54 pages) |

| Fire | 239-297 (59 pages) |

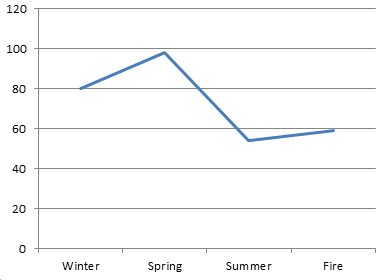

And the next thing we do? We plot the numbers on a graph so we can see a visual representation of the section lengths:

What do we notice? “Spring” is the longest section and the final two are much shorter than the others. Why does this make sense? In “Winter” and “Spring,” Mr. Ruland has a lot of pipe to lay so the end of the narrative will flow. Further, once we get to the climax, we (as readers) just want to go go go and Mr. Ruland shrewdly gives us what we want.

What do we notice? “Spring” is the longest section and the final two are much shorter than the others. Why does this make sense? In “Winter” and “Spring,” Mr. Ruland has a lot of pipe to lay so the end of the narrative will flow. Further, once we get to the climax, we (as readers) just want to go go go and Mr. Ruland shrewdly gives us what we want.

Is a structure of this shape mandatory? Of course not. A storyteller’s First Commandment is that the structure of the piece must, above all, serve the narrative and its characters. The three protagonists (perhaps four, depending on how you look at it) have complicated backgrounds and the author takes the time to throw in a flashback here and there and to give us a complete understanding of who the characters are and why we should care about them.

It’s not fair to say that Forest of Fortune resembles The Twilight Zone exactly. The latter is an idea-driven TV program (often) capped with twist endings and whose plots are as compact as the amount of characterization. The book and the program do have something interesting in common: both feature climaxes that are placed at the VERY end of the piece, leaving very little time for denouement. (The establishment of the characters’ new status quo.)

You probably noticed that the last section of the book is, as they would say on Sesame Street, is not like the others. It’s not the same. The title of the section gives you a little hint with respect to the big event that ushers the characters into a new point in their lives. Why do I bother pointing this out? Such a structure creates a cool effect. Mr. Ruland does not spell out every last detail as to what will happen to the characters. Instead, his characters endure a stressful situation and the reader is given clues to help them divine the futures they have in store.

The same effect can be found in a classic film: 1984’s The Terminator. Sarah Connor, of course, has killed the T-800 and knows she must now bear and protect the man who will eventually fight the machines. She retreats into the countryside. James Cameron offers us a very brief gas station coda in which we’re informed that Sarah has accepted her mission and that she loves Kyle Reese. Then Sarah drives off into the stormcloud-blanketed horizon:

We don’t get a TON of information, but we have a pretty good idea of what Sarah Connor’s future holds…a tough climb in difficult weather.

One of the things I admired most about Forest of Fortune is the way Mr. Ruland uses descriptive imagery. For example:

As Lupita labored up the grade, she wondered why some mountains out here on the outskirts of the desert were jacketed in soil while others resembled piles of boulders stacked by a gigantic hand. Not for the first time she wondered how two mountains could be the same height and shape, but so different. One covered in verdant scrub, the other rocky and barren. They sat side-by-side, inviting comparison. Similar but different, like Lupita and Mariana.

Denise reminded Lupita of her mother, who dealt with people the way a machete sliced through fruit.

Pemberton had no recollection of sending, typing, or even thinking these [text] messages. His bafflement was total, his confusion complete. Did his inner O’Nan send Debra these texts? He was still wearing the name tag from the seminar, only Pemberton had been crossed out, and now it said: LIKE YOU CARE.

So the sentences are pretty. But more importantly, the beautiful language gets work done for Mr. Ruland, putting across plot and/or characterization. I suppose that I’m touching upon one of the big differences between the composition of poetry and narrative. I’m certainly not saying that poets NEVER describe characters or plots. A poem, however, is more likely to be a short burst that places a lot of beautiful responsibility on the reader to interpret meaning. On the other hand, a short story or novel requires each element to serve a far larger whole. It’s like tennis versus baseball: a singles player is fully responsible for getting a win, but a baseball player has several colleagues on whom he must rely for victory.

Above all, Forest of Fortune is a fun novel about serious issues. How can we overcome our big problems? How do we leave behind the disappointments, self-created and otherwise, that have made us miserable? What does it take to get out of the doldrums? Can we simply outrun these problems or are they simply too fleet of foot?

What Should We Steal?

- Analyze the structure of your work to ensure you’re emphasizing the proper parts of the narrative. In general, the work you do to establish your climax should take up many more pages than the climax itself.

- End your work with only the suggestion of future events. Ambiguity, depending on the specific story, can be your friend.

- Charge every element of your story to accomplish narrative work, including description. Stories should have no dead weight; make your sentences multi-taskers.

You know, I’m watching the semiannual Twilight Zone marathon, and one episode reminded me of you - I knew you’d referred to TZ but I couldn’t remember how or where. Turns out, not the way I thought, but no matter.

The episode is “Hocus, Pocus & Frisby“, not one of the best episodes (wall-to-wall cliches, in fact) but what struck me was the narrative structure, and it’s common to almost all the episodes: open on a scene in “before” state, in this case, a bunch of good ole boys, one of them a champion tall-taler, chatting in a general store. Pure “show”, letting the viewer draw conclusions from the way the other characters react to his stories. Then, after almost 5 minutes (one of the longer preludes), Rod Serling comes on and does some exposition - not backstory, exactly, but makes sure the viewer got the point (that the guy is a liar) and introduces the “turning point” where the complications begin - “he’s about to enter the Twilight Zone”. This is to keep us tuned through the commercial break, but many stories do the same thing to keep us reading, indicate a change is coming.

Funny, how I’ve started seeing tv in narrative terms. 😉 Never occurred to me to look at TZ that way, but that’s because it’s such a rare treat.

Interesting. “Hocus” is not one of the episodes I know by heart. I will re-watch it without distraction. (It’s a later episode; I’m a tad weaker on those.)

I am so tickled that you thought about me while watching The Twilight Zone. I’ve been a fan for as long as I can remember and I even wrote a couple reviews of work derived from what Serling did. (Serling and I have tangential connections; he grew up in Binghamton, NY, but visited Syracuse, NY and I grew up in those suburbs. And he went to college in Ohio, the state in which I attended grad school. Ooh! Memory! I went to Disney World on a high school Vocal Jazz trip and had a picture of myself taken with a bust of Serling. And I pushed myself to write a script in fewer than 24 hours, as I had heard Serling did…)

I’m quite inspired by your analysis and I should write up a proper Twilight Zone GWS essay. You’re right about the structure.

“People Are Alike All Over”: The astronauts BEFORE the mission…Serling comes in for exposition/tone, etc.

“Time Enough at Last”: IIRC, Mr. Bemis loves to read, is oppressed…Serling comes in for exposition/tone.

“To Serve Man”: Ooooh…this one is tricky. We see Mr. Chambers after his fate is sealed (no spoilers!)…I can’t remember where Serling comes in before the rest of the story is told in flashback (before Chambers’s bookend).

There’s so much to learn from Serling about narrative. Smart people like you (and me?), it seems, are fortunate enough to understand and enjoy great works on multiple levels. I’m trying to say that I hope I don’t take away from your enjoyment of The Twilight Zone in terms of pure story.

And have you seen the 1980s and early 2000s remakes? Some are quite good and even the ones that aren’t are worth our time. (Ooh, and the 1990s Outer Limits were pretty cool, too.)

I suspect many MFA theses (and possibly an English Lit dissertation or two) have used TZ; some of his eps were blends of Poe and O. Henry (The Masks, The Silence) and his Redemption arcs are amazing (“One for the Angels”, the one with Art Carney as Santa Clause, I can’t remember the title).

I’ve seen a bunch of “new” eps from various similar series, but I can’t remember which was which, and I rarely remember individual episodes… except for… it was from a short story… Ah, there it is (that’s what Google is for) - Mare Winningham, “Button, Button” - nicely done, it was obvious where it was going, but the final line delivered it nicely (“It will be someone you don’t know…” there must be an MFA word for that, a line that echoes something in another context that now has completely different implications, some kind of irony?).

TV is a gold mine for narrative, and it’s not just Sorkinesque dialogue and walk-and-talks (though I spent my light-workload December binge-watching The West Wing thanks to the try-it-free month from Netflix). In an article for The Short Review, my buddy Marko Fong wrote about the elements of TV narative, specifically, The Mary Tyler Moore Show, as a way of describing Egan’s The Goon Squad; was it you or Paul Debrasky who wrote about How I Met Your Mother (the “Suits” song, probably was you) as an amalgam of storytelling styles? I could never follow the show, probably because it refused to follow a single path (I’m one of the stupid sheep who couldn’t adapt, but it seems they didn’t need me).

Even bad tv can be used to study narrative and character construction: When I was doing Project Runway recaps, finding the narrative theme for the season was a project. I quit recapping and watching when they brought out the Scary Black Man trope, but that was long after they drove the show into a ditch. Reality tv in general goes to great lengths to create recognizable patterns - the hero, the screwup who learns a lesson, the scoundrel who either gets redemption (even if it takes an All-Stars ep to do it, Tiffany Faisson) or meets a fitting end, the Comeback, etc.