What Can We Steal From Janelle DolRayne’s “In the style of Joan Mitchell”?

Title of Work and its Form: “”In the style of Joan Mitchell”,” poem

Author: Janelle DolRayne

Date of Work: 2014

Where the Work Can Be Found: The poem debuted in the October 2014 issue of inter | rupture. You can find it here.

Bonuses: Here is an apt poem that was subsequently chosen for Best of the Net 2013. Here is a reading list that Ms. DolRayne put together in her capacity as Assistant Art Director for Ohio State’s The Journal. Want to see the poet read her work?

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Conceits

Discussion:

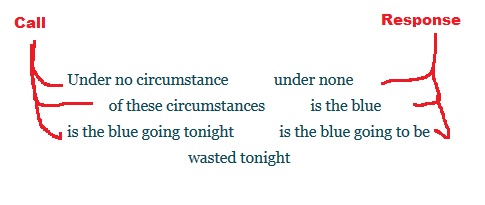

Ms. DolRayne offers us a poem with a fun and interesting conceit. (It bears mentioning that Ms. DolRayne may not have the same idea as I do about her poem…but that’s okay.) It seemed to me that the poem is a powerful attempt to use poetry to mimic the loose and quietly powerful feel of a folk song. If you’ll notice, the first few stanzas feature lines that employ the call-and-response technique popular in folk, blues and rock music:

You’ll also notice that the last stanza abandons the conceit, which is perfectly fitting. The narrator of the poem is now speaking in “unison” or “a cappella.”

You’ll also notice that the last stanza abandons the conceit, which is perfectly fitting. The narrator of the poem is now speaking in “unison” or “a cappella.”

First, I’ll give you some examples of the call and response I’m talking about. Phil Medley and Bert Berns wrote “Twist and Shout,” a song that was covered by a lot of groups, including The Beatles. You’ll notice that the background vocalists mirror and augment the lead singer.

Steven Page and Ed Robertson wrote “If I Had a Million Dollars.” As I understand it, Ed had written the bulk of the song, but only had his part of the vocal. Mr. Page heard the song in progress and added his part. Mr. Page sometimes simply repeats Mr. Robertson’s part; sometimes he adds to the narrative of the song and takes it in a new direction.

The response doesn’t even have to come from a vocalist. In George Thoroughgood’s “Bad to the Bone,” the response comes from guitar and saxophone.

I loved Ms. DolRayne’s use of this technique for a number of reasons:

- Poetry is just a kind of music, right? Why not make that connection explicit in this way? Some people think poetry is a fancy-pants thing you read because some teacher told you to. Those same people love music without realizing poetry does many of the same things.

- The “call and answer” adds another voice to the poem, even though it’s only being written by one author. In this way, we’re able to produce a kind of harmony.

- The images and ideas in the poem are reinforced through repetition and through being conceptualized in a different way.

- The phrases on each side of the large spaces can be considered poems unto themselves and these poems are in conversation with each other, aren’t they?

One of the inherent difficulties in writing is bridging the gap between thought and the written word…and trying to figure out how to combine words, space and punctuation in such a way that the reader will understand the thought you had. Ms. DolRayne literally adds in the pauses that led me to treat her poem like a kind of song. For the poet, those pauses are spaces between words. For a singer, those pauses are bits of silence between musical phrases. Why not take Ms. DolRayne’s idea and try to lay down some prose in the style of a musician?

I think one of the reasons that I identified the call-and-answer conceit in the poem is because the poem was challenging me, inviting me to make sense of it in a way that made me happy. If you’re near a window, look out at the clouds. What shapes you do see? A phenomenon called “pareidolia” forces us to make sense out of “vague or random” stimuli.

Now, that’s not to say that Ms. DolRayne has given us a poem filled with randomness, because she didn’t. That’s writing craft in a nutshell, folks. The poet had to work very hard to create a work that clearly communicated her own thoughts while ensuring the piece was open enough to allow the reader to draw his or her own conclusions.

Unfortunately, there’s no easy method by which writers can learn to be simultaneously specific and vague. That’s just not something you can learn with a step-by-step procedure. Instead, we just need to read a lot of poems and write a lot of poems and hope that our skills improve to the point where we have the power to turn any trick we like.

What Should We Steal?

- Think of yourself as a songwriter when you compose. The conventions of music are not exactly the same as the ones writers use, but we can use their prose equivalents to our advantage.

- Trigger your reader’s pareidolia. How can you get your reader to see the plan in what seems like randomness?