Show Notes:

Enjoy this interview with Christy Crutchfield, author of How to Catch a Coyote, a novel published by Publishing Genius Press.

Find out more about Christy Crutchfield at her web site.

http://www.christycrutchfield.com

Order your copy of her book from her publisher:

http://www.publishinggenius.com/?p=3347

Or you can order your copy from your local indie bookstore:

http://www.indiebound.org/book/9780988750388

Or you can order the book online the old-fashioned way:

http://www.powells.com/biblio/62-9780988750388-0

Visit my website: http://www.greatwriterssteal.com

Like me on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/GreatWritersSteal

Follow me on Twitter: @GreatWritersSte

Music: “BugaBlue,” Live At Blues Alley by U.S. Army Blues is licensed under a Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

http://freemusicarchive.org/music/US_Army_Blues/Live_At_Blues_Alley/

Many thanks to the Library of Congress for their beautiful public domain image:

http://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/nclc.00097/

Short Story Collection

2014, Christy Crutchfield, How to Catch a Coyote, Publishing Genius Press, The Great Writers Steal Podcast

Title of Work and its Form: “God,” short story

Author: Benjamin Nugent

Date of Work: 2013

Where the Work Can Be Found: “God” made its debut in Fall 2013’s Issue 206 of The Paris Review, one of the biggest journals around. The story was subsequently chosen for Best American Short Stories 2014 and can be found in the anthology.

Bonuses: Listen to this audio interview Mr. Nugent gave to The Lit Show‘s Ben Mauk in support of his novel, Good Kids. Here is “The Rugby Witch,” a story that was published in The L Magazine. Here is a fun video in which Mr. Nugent discusses the word “nerd:”

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Audience

Discussion:

The first person narrator is a college student and a member of the Delta Zeta Chi fraternity. The frat’s world has been turned upside down by God. No, not a supernatural being. God is the nickname they have given to Melanie, a young woman who has captured the heart of their leader, Caleb Newtown-also known as “Nutella.” Melanie flexed her literary muscles, penning a poem about Nutella’s problem with premature ejaculation. God’s revelation moves each frat brother’s heart in different ways. Five-Hour nearly manages to have sex with God, but he is prevented from doing so because of a little bit of erectile dysfunction. The story’s climax is the expected one, but Mr. Nugent does a good job of imbuing the story with far more weight than such a piece might otherwise have.

There’s so much to admire about this story, but I’ll begin with the point I was just making. I often mention my preoccupation with “the woman on the bus.” Lee K. Abbott, my stellar teacher at Ohio State, used this idea to describe the kind of audience he has in mind when he writes. I sometimes worry that our literary community has become too insular; that we’re not making as many new readers as are necessary to keep us going. Are we dealing with subject matter that is too esoteric for the mainstream? Are we abandoning plot and other elements that are attractive to a wide audience? We’re competing with TV, film, texting and the Internet, after all. Why can’t more “literary” work be “fun?”

This is a story about romantic attraction and its resultant sexual complications. People are interested in reading about that. This story is funny; I made at least half a dozen smiley faces in my copy. People like laughing. The story is packed with beautiful sentences, but Mr. Nugent keeps the story humming along nicely. I suppose that what I’m saying is that writers of literary fiction should follow Mr. Nugent’s lead and tilt the scales just a little bit more in the direction of entertainment as a priority. Art feeds the heart and mind; perhaps we should make the heart a little more prominent in what we produce.

“God” is a story predicated upon a classic and powerful conceit. For months, the world of Delta Zeta Chi and its members was stable. The brothers cared about each other, everyone admired Nutella and everyone had complementary goals. That was before Melanie/God showed up and turned Delta Zeta Chi upside down. After the young woman writes the poem, the social order and heirarchy of the frat is destabilized. Instead of doing what they can to find their own girlfriends, many of the brothers want to enjoy special time with M/G, as though having sex with her will transfer some of Nutella’s power to them. And the narrator has some very interesting reasons for wanting to have sex with her…

Think of the previous paragraph and replace all of the mentions of the frat with “Camelot.” Wow! It’s pretty much the same story! All is good in Camelot until that darn Lancelot comes around, pretending he’s all moral and high-minded…until Guinevere makes eyes at him. Writers are often interested in building worlds. What happens if you decide to destroy a world instead?

What Should We Steal?

- Lighten up and entertain. Should we go full Kardashian? Of course not. (That’s a gross mental image.) Perhaps we should be just a little more cognizant of the need to attract and keep more readers.

- Begin with a nice, stable subculture and setting…then shake it up. The Republic is doing just fine…until the Senate elects the obvious bad guy to be Emperor. The proverbial marriage is doing just fine…until one partner gets a couple hangup phone calls.

Short Story

2013, Audience, Benjamin Nugent, Best American Short Stories 2014, The Paris Review

Title of Work and its Form: “La Pulchra Nota,” short story

Author: Molly McNett

Date of Work: 2013

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story debuted in Issue 78 of Image. “La Pulchra Nota” was subsequently chosen for Best American Short Stories 2014.

Bonuses: Check out One Dog Happy, the collection Ms. McNett published through University of Iowa Press. Here is an interview Ms. McNett granted to one of her former students. Here is “Lonesome Road,” a piece of creative nonfiction that Ms. McNett published in Brain, Child. Check out Karen Carlson’s powerful analysis of the story.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Historical Fiction

Discussion:

John Fuller is a 29-year-old man who was, as he says, “born in the year of our Lord 1370.” He informs the reader that he has suffered a “grave accident” and no longer has use of his hands. Fuller tells his story with the help of a scribe and does so beautifully. Fuller was born with eyes that cast their gaze askew; his aesthetic misfortune led him to marry the first and seemingly only woman who would have him. Katherine is from a wealthy family and their lives are happy enough until their beloved twins die. As Katherine retreats from Fuller, one of his voice students gives him the attention that he has always craved. Olivia is a small wisp of a young woman who manages to produce “la pulchra nota,” a heavenly sound. She confesses her love, Fuller does a little too much thinking about the young lady and, well, just read the story. It’s a knockout.

I know…I know…there are about eleventy trillion stories that are set in the past and historical fiction is its own genre. I guess that I just don’t recall seeing too many in literary journals…and this is a shame because these kinds of stories are so much fun! In a way, a story like “La Pulchra Nota” turns the reader into a time traveler. What would it be like to stop by a bookstall and to buy a Shakespeare Quarto? What was it like to live during the American Revolution and discover that you are married to a Tory? Did Egyptian slaves have any time for romantic longing during the time they were building the pyramids? (And could love set them free to any extent?)

Ms. McNett is also smart enough to sidestep many of the challenges inherent in the composition of historical fiction. Do you know everything about fourteenth-century England? Me, neither. I’m wondering how well I could even communicate with John Fuller if we met; after all, he grew up in the time of Chaucer. Ms. McNett doesn’t focus too closely on the clothing, language, food, science or customs of her specific time and place. Instead, she keeps our attention on what we share with John Fuller, Katherine and Olivia. Humans still suffer disabilities and disfigurement…we still love our children and mourn their untimely deaths…we still have sexual longing and can be driven to extremes when our needs in that arena are not met.

Ms. McNett’s use of Christian mythology is also a “binding agent.” Whether or not you are an actual Christian, you are no doubt familiar with the worldview that puts stress on the Fuller marriage. You are willing to ignore your curiosity about some of the finer details because you understand what it means when Ms. McNett writes:

- “…divine providence was pleased to take the life of our dear twins…”

- “…every devout man knows the great mercy he shows us in taking a child out of the world.”

- “…it pleased the Lord to take to paradise my father the organist…”

Another facet of the story that I admire is the way Ms. McNett employs the first person. After making it clear that Fuller is disabled, she has her protagonist unspool his life story. In the hands of a lesser writer (someone like me), this story could have been pretty boring. Instead, Ms. McNett focuses on the important, interesting and necessary moments in Fuller’s life. We need to know about his disfigurement and how it happened and about his marriage and how and why everything changed. Ms. McNett doesn’t bog the narrative down by including extended sections about where Fuller bought his food or what his education was like or anything else that would seem superfluous. I love Les Miserables a ton, but you have to admit that some of the sections about the Paris sewer system aren’t quite as necessary as the scenes with Fauchelevent. “La Pulchra Nota” never stops moving and that’s why we love the story. Ms. McNett follows the advice of the great Elmore Leonard, whose tenth rule of writing is:

“I try to leave out the parts that readers skip.”

What Should We Steal?

- Set your story in the distant past. If we learned nothing else from The Twilight Zone, it’s that people are the same all over. Mix things up by dispatching your Muse into centuries gone by.

- Focus on the commonalities we share with old-time characters, not our differences. Our ability to understand and/or relate to a character is more important than knowing what kinds of spice to which the protagonist has access.

- Obey Elmore. Leave out the boring parts.

Short Story

2013, Best American Short Stories 2014, Historical Fiction, Image, Molly McNett

Title of Work and its Form: “Charity,” short story

Author: Charles Baxter

Date of Work: 2013

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story debuted in Issue 43 of McSweeney’s. Heidi Pitlor and Jennifer Egan chose to include the work in Best American Short Stories 2014.

Bonuses: Karen Carlson always has some interesting thoughts to share, this time about Mr. Baxter’s story. Here is a Midwestern Gothic interview in which Mr. Baxter discusses his connection to the region. Want to see what Mr. Baxter said about his work at St. Francis College?

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Point of View

Discussion:

When Matty and Harry met, they were Americans living in Africa, doing what they could to help sick people. Harry loved that Matty/Quinn was filled with kindness for the people around him and wasn’t helping out in hopes of making a profit. As the Bard might say, the course of true love never did run smooth. Though they remain boyfriend and boyfriend after returning to the States, Matty ends up living in a friend’s basement, addicted to the painkillers that are his only relief from the pain caused by a sickness even the Mayo Clinic can’t identify. The story is split into two sections; the first describes the dire straits in which Matty finds himself and the second is a first-person account of Harry’s trip to Minneapolis to find and help his boyfriend.

Mr. Baxter tricked me! Ever since grad school, I’ve been in the habit of jotting down the story’s point of view and the names of the important characters. Doing so helps me remember the story the next time it’s brought up and addresses one of my blind spots: I’m REALLY bad at remembering character names. So I started reading “Charity:”

I

He had fallen into bad trouble. He had worked in Ethiopia for a year…

So I uncapped my fountain pen and wrote: 3RD and eventually QUINN. All was well and good until I reached the next section:

II

That was as far as I got whenever I tried to compose an account of what happened to Matty Quinn-my boyfriend, my soulmate, my future life…

Uh oh. That’s first person. What’s going on? Well, Mr. Baxter has made a fantastic choice: that’s what’s going on. Even though Harry most certainly asked Matty about what happened in Minneapolis, he was not there for every moment. The story therefore benefits from casting the first section in third person. The narrator (Harry, in this case) is able to immerse the reader in the story much more deeply than if he had to tell the tale from a distance. Further, the first section really does belong to Matty; he’s the protagonist in the events, he’s the focal character…so the story SHOULD be told from his perspective. The second section, on the other hand, is very much Harry’s story. He’s the one who meets up with Black Bird and who does what he can to bring Matty back to life.

If you’re lucky enough to have the Best American volume, you can read the end notes that accompany each story. Mr. Baxter reveals the most fascinating piece of information regarding the genesis of “Charity:”

…I had just written a story called “Chastity,” in which my protagonist, Benny Takemitsu, gets mugged, and I thought, “I wonder who did that?” Whoever did it had to be desperate. Whoever it was, I thought, might be a good soul in the grip of something truly terrible. So I wrote it that way.

Isn’t that cool? Mr. Baxter’s choice offers a couple powerful advantages:

It’s really hard to come up with story ideas, isn’t it? Cherry-picking an event from another of your works can be the inspiration that gets you going on a new story. If you look at any of your stories, you’ll surely see all kinds of avenues ripe for exploration. Hmm…here’s what I’m thinking I could poach from my story, “Something Like a Sin:”

- Who are some of the other people who attend Transformation Baptist? What are they like?

- What else could happen in The Raven, the bar the protagonist frequents?

- What is Pastor Hocking’s family like? When has he failed to live up to his own standards?

- What happened with all of the other women the protagonist mentions?

- Who is in the house when Melody closes the door behind her?

See? If I’m dry for inspiration, looking to my past work can give me a jumpstart.

Mr. Baxter also gains something very important by reusing Benny Takemitsu’s mugging: he’s creating a discernible world. Isn’t it comforting to know that all of the Marvel characters know each other and can sometimes team up, for good or evil? Tying these two stories together makes Mr. Baxter’s Minneapolis seem more like a real place. Creating the mythology is also a good idea in light of the fact that Mr. Baxter is publishing a collection of stories about “virtues and vices:” Chastity, Charity, Refraining From Watching the Next Breaking Bad Episode on Netflix Before Your Spouse Does, and so on. A shared world only strengthens the conceit of the book.

What Should We Steal?

- Tell your story from the most appropriate and interesting point of view. Sure, you may have to break your story into sections and change POV, but that’s okay if it’s done in the service of the story.

- Borrow characters and situations from your other works. Even if it’s just a cameo from another character’s friend, people who read your work will find greater depth in the world you create.

Short Story

2013, Best American Short Stories 2014, Charles Baxter, McSweeney's, Point of View

Show Notes:

Enjoy this interview with Sarah Tregay, author of Fan Art, a young adult novel published by Katherine Teger Books.

Find out more about Sarah Tregay at her web site. You will also find links to retailers that will be happy to sell you her book:

http://www.sarahtregay.com/

You may also follow my example and purchase Fan Art from an independent bookseller. I got my copy from the river’s end bookstore in Oswego, NY.

http://www.indiebound.org/book/9780062243157

Keep up with Sarah Tregay on Facebook:

https://www.facebook.com/sarahtregaybooks

Young Adult Books Central is a great resource if you want to learn more about YA books:

https://www.facebook.com/YABooksCentral

If you are a YA yourself and you want to learn more about writing, check out Go Teen Writers:

http://goteenwriters.blogspot.com/

I have also written several essays that will help YA writers hone their craft:

http://www.greatwriterssteal.com/tag/young-adult/

Visit my website: http://www.greatwriterssteal.com

Like me on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/GreatWritersSteal

Follow me on Twitter: @GreatWritersSte

Music: “BugaBlue,” Live At Blues Alley by U.S. Army Blues is licensed under a Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

http://freemusicarchive.org/music/US_Army_Blues/Live_At_Blues_Alley/

Video

Fan Art, GWS Video, Sarah Tregay, The Great Writers Steal Podcast, Young Adult

Title of Work and its Form: Ransom, novel

Author: Jay McInerney (on Twitter @jaymcinerney)

Date of Work: 1985

Where the Work Can Be Found: The book can be found in most great independent bookstores. (If they don’t have Ransom in stock, the kind booksellers will be happy to order it for you.) You can also order the book online.

Bonuses: Here is Susan Cheever’s contemporary review of the book for the Chicago Tribune. Here is an exclusive PBS video in which Mr. McInerney discusses when George Plimpton accepted one of his stories for The Paris Review…his first publication. Here is a short story that Mr. McInerney published in Five Chapters in 2007…twenty years after the piece was stolen from his apartment.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Clear Sentences

Discussion:

Christopher Ransom is a young man who has been unofficially exiled to Japan. He doesn’t want to spend time with his shallow TV producer father in California, and what took place at the Khyber Pass unplugged him from the rest of the world. So Ransom teaches English to eager Japanese students and has spent two years learning discipline from the martial arts. Unfortunately for him, Ransom is not destined to have a relaxing, carefree life. A Vietnamese singer is dating one of his friends, another American ex-pat. She’s also dating a man in the Yakuza. (Talk about external conflict!) “Frank DeVito, ex-Marine and current Bruce Lee clone” seems to have it out from Ransom, too. Through the course of this quick read, the protagonist finds the answers to some of the big questions that have been haunting him for some time and have shaped his life. (Yes, that’s cryptic. Just read the book!)

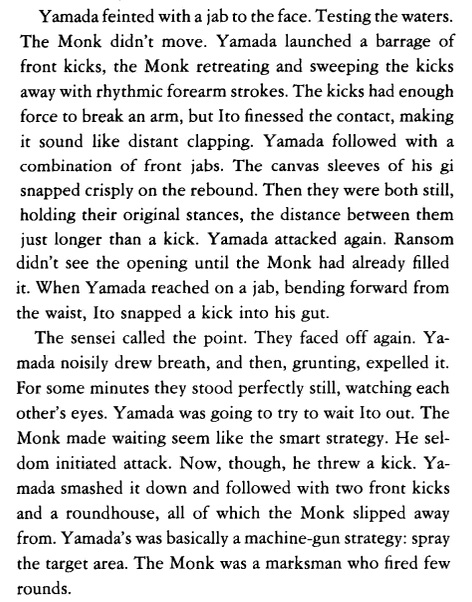

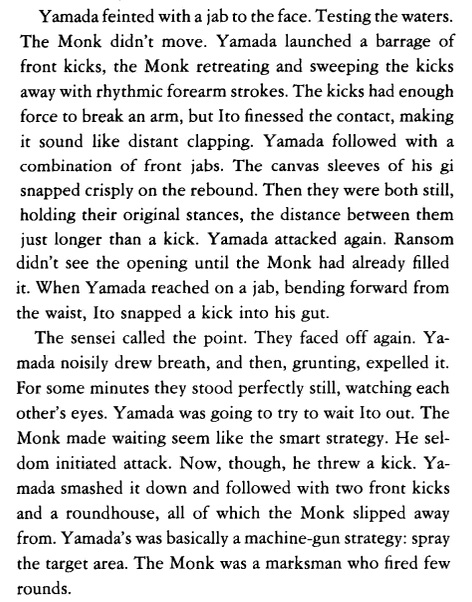

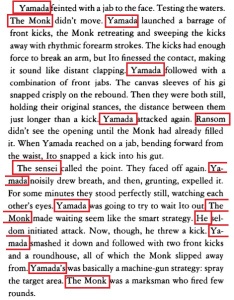

One of the things that impressed me most about Ransom was the way Mr. McInerney began the book. While this novel is certainly “literary” (for whatever that means), the author does not kick off the narrative with, for example, a dry description of the history of the sod behind the family farm and how each blade was influenced by the ten generations of family members who had tilled it. Zzzzzz. No, Mr. McInerney jumps out of the gate with a scene at Ransom’s dojo in which we learn what the protagonist has been doing in the Land of the Rising Sun. Even better, we get to read a scene in which two of Ransom’s colleagues are sparring. Here’s an extract:

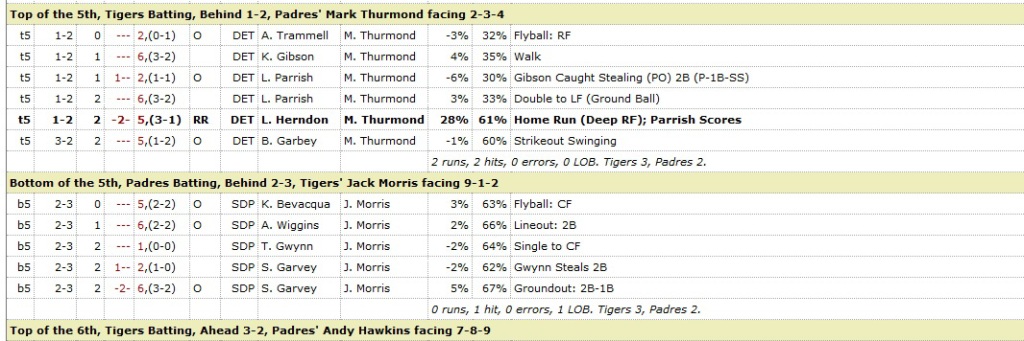

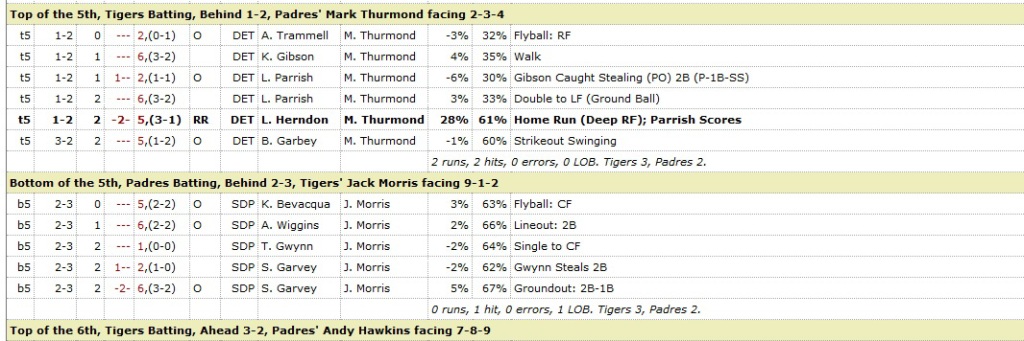

Look at how clear the sentences are! Now, Mr. McInerney certainly has the ability to unspool some complicated and beautiful sentences, but he reins himself in here: a good idea considering that he’s essentially providing a play-by-play for what is very much a visual series of events. Some things are better seen than described, right? At times, however, we writers are required to cast prose examples of visual events. Which would you rather do? Watch Game 5 of the 1984 World Series or read a written account of what happened?

Look at how clear the sentences are! Now, Mr. McInerney certainly has the ability to unspool some complicated and beautiful sentences, but he reins himself in here: a good idea considering that he’s essentially providing a play-by-play for what is very much a visual series of events. Some things are better seen than described, right? At times, however, we writers are required to cast prose examples of visual events. Which would you rather do? Watch Game 5 of the 1984 World Series or read a written account of what happened?

or

?

Here’s the challenge: how do you end a chapter in a way that gets your reader’s pulse pounding while simultaneously stimulating his or her intellect? Let’s break down what Mr. McInerney did with his sentences:

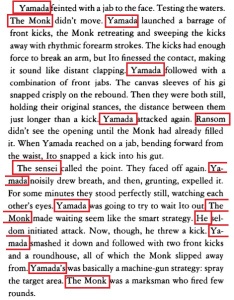

- Many of the sentences begin with their subject:

Beginning with the subject of the sentence is a felicitous move because the reader has no trouble keeping track of the characters involved in the fight. These kinds of lines could get a little boring if they fill a whole book, but this sing-songy approach (“Bob did this. Sally did that. Bob did that back. Sally did that back to Bob”) is helpful in small doses.

Beginning with the subject of the sentence is a felicitous move because the reader has no trouble keeping track of the characters involved in the fight. These kinds of lines could get a little boring if they fill a whole book, but this sing-songy approach (“Bob did this. Sally did that. Bob did that back. Sally did that back to Bob”) is helpful in small doses.

- Powerful verbs follow those proper nouns. Aren’t these the first kinds of sentences we learn to write? “Sally ate some cake. Bob asked for some. Sally offered him a piece of cake.” Again, employing simple and clear sentences allows us to enjoy the fight unfolding in front of Ransom. Even better, these verbs are strong: “feinted…launched…followed…attacked…”

- The sentences are fairly short. I just re-read B.R. Myers’s “A Reader’s Manifesto,” so my ears are still ringing with his excoriation of writers who offer us complicated sentences that he feels are deliberately opaque. There are no opaque sentences in these paragraphs.

Mr. McInerney shifts point of view just a little bit in the book. Doing such a thing is ordinarily a cardinal sin and a sure way to invite constructive criticism from a workshop colleague or a first reader. Mr. McInerney, however, switches to DeVito’s perspective by necessity. Why? Some of the events that shape Ransom’s life and fate take place far away from Ransom, who can’t and shouldn’t be privy to them. Further, the climax and conclusion of the book is rendered more satisfying because of these shifts in the point of view.

More importantly, Mr. McInerney may flip between consciousnesses, but he never takes his narrative focus off of Ransom. (The book bears his name for a reason!) I think this is a case of “don’t break the rules until you know them.”

What Should We Steal?

- Mimic the style of prose Mr. McInerney used in his fight scenes when you are describing acts that are particularly visual in nature. Offer short sentences with powerful verbs and try to keep the subject of the sentence at the beginning.

- Avoid shifting your point of view unless you have some really good reasons. Like any other kind of violation, slapping your reader into the POV of another character is acceptable, so long as you are serving your larger narrative.

Novel

1985, Clear Sentences, Jay McInerney, Robert O'Connor, Syracuse University

Title of Work and its Form: Tough Guys Don’t Dance, novel

Author: Norman Mailer

Date of Work: 1984

Where the Work Can Be Found: The book can be found in most cool secondhand bookstores. I’m willing to bet that list includes Provincetown Bookshop. (I could easily be mistaken-the time I spent on Cape Cod seems in my memory to have been lived by a character in someone else’s movie, but I seem to recall visiting that store and enjoying my time there a great deal.) You can purchase the book from your local indie or get it from a much larger indie.

Bonuses: The Norman Mailer Society is dedicated to preserving the legacy of Mr. Mailer’s work. J. Michael Lennon offers this brief appreciation of Mr. Mailer’s work. Mr. Mailer was a frequent talk show guest and this documentary was made about him after his death:

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Genre

Discussion:

The novel starts on the twenty-fourth morning after Tim Madden’s wife decided she wanted to fly the coop. Madden is hung over and has a new tattoo on his arm: the name of a woman from his past. The passenger seat of his Porsche is drenched in blood. Over the course of the next several days, Madden unravels the mysteries that he only thought began when he met the beautiful rich blond and her ugly husband in his favorite Provincetown watering hole.

That’s right, the book is essentially a high-class pulp novel in the style of Mickey Spillane or Donald Westlake. Now, I love those kinds of books. I don’t aspire to the gunplay or liver damage, but isn’t it fun to spend a few hours in a completely different world? A place in which it’s not unusual to kiss The Dame Who Got Away or to walk into a room and smell evidence emanating from your gun that could put you back in the clink?

The first matter of craft that impressed me about Tough Guys Don’t Dance was the way in which Mr. Mailer attempted to “class up” a genre that is often unfairly maligned by critics. Okay, a lot of pulp novels are weighed down by cliches and clunky sentences. Fine. But STUFF HAPPENS in these books. The characters are FUN. There is MEANINGFUL SUSPENSE. Pulp detective novels are the spiritual forbear of TV programs such as Law & Order: SVU, a program that currently averages eight million viewers each Wednesday night. How many short stories are read by eight million people? How many books sell that many copies? (Gracious; if these numbers are to be believed, Catch-22 has only sold ten million copies!)

I suppose that what I’m urging at the moment is that we all make more of an effort to appreciate genre work and try our hands at branching out from what may be our comfort zones. Of course, writers are well within their rights to compose whatever works they like. But how cool would it be if Alice Munro took a crack at a post-apocalyptic science fiction thriller? What if John Irving woke up one morning and decided to write an epic fantasy poem? Perhaps it’s my personal preference speaking, but I love it when a great writer uses his or her most powerful gift-imagination-as completely as possible.

Now, what makes Tough Guys Don’t Dance a “high-class pulp novel?” I would assert that the book sets itself apart on the “literary” side by devoting a lot of time to characterization at minor expense to the laying of plot. In an Ed McBain book or a Day Keene book, the plot is always chugging along. Sure, McBain and Keene establish characters (and very cool ones), but Mailer devotes dozens of pages to backstories for Madden and his colleagues. Still, Mr. Mailer makes the shrewd choice of ending each chapter with a big, important and cool event, a revelation that makes us wonder what will happen next.

Chapter One: “Yet none of these scenarios, nor very little of them, can be true-because when I woke in the morning, I had a tattoo on my arm that had not been there before.”

Chapter Two: “…I did not even know whether it was the head of Patty Lareine or Jessica Pond lying in that grave. Of course, I also did not know whether I should be afraid of myself, or of another, and that, so soon as night was on me and I tried to sleep, became a terror to pass beyond all notions of measure.”

Chapter Four: “The head was gone. Just the footlocker with its jars of marijuana remained. I fled those woods before the spirits now gathering could surround me.”

Here’s the challenge: how do you end a chapter in a way that gets your reader’s pulse pounding while simultaneously stimulating his or her intellect?

What Should We Steal?

- Break out of your genre safe space and try something new. Why not dip your toe in the warm waters of crime, science fiction, fantasy or western stories?

- End your chapters with meaningful developments that advance the plot and will grab the reader on a high and low level. We read with our minds AND our hearts. Why not stimulate both?

Novel

Classic, Genre, Norman Mailer, Random House

Friends, the past few days have seen gallons of digital ink spilled over a controversy arising from Lena Dunham’s recent memoir, Not That Kind of Girl. The book is a set of essays in which Ms. Dunham discusses her life and her philosophies and was highly anticipated by fans of her HBO program Girls. Perhaps no one was more excited for the book than Random House, who paid Ms. Dunham a $3.7 million advance for the book. (Rob Spillman wrote a very interesting article about the advance for Salon.)

The controversy began a month after the book’s release when Kevin D. Williamson published a scathing piece in the National Review in which he quoted passages from Not That Kind of Girl that could easily be considered descriptions of child sexual abuse. Truth Revolt followed suit, quoting the same passages from the book; Ms. Dunham’s attorneys have threatened to sue the site.

I must begin this discussion by pointing out that I have taken great pains to maintain Great Writers Steal’s neutrality when it comes to politics and other controversial issues. I certainly have my own opinions that are hewn, I like to think, by my open-mindedness and dedication to reason and free discourse. You may think whatever you like about Ms. Dunham and Girls and her place in popular culture. GWS is a place where we discuss writing craft-related dilemmas; I am slowly working my way to making my argument that the Not That Kind of Girl kerfluffle raises a number of important issues with respect to creative nonfiction:

- When are we oversharing?

- How do we navigate tone when discussing sensitive situations?

- What reaction should we expect when we confess?

- What should we do when we get an unanticipated reaction to our work?

- Perhaps most importantly: when are we being too honest?

We certainly can’t discuss the current Lena Dunham situation without taking a look at the extracts in question, can we?

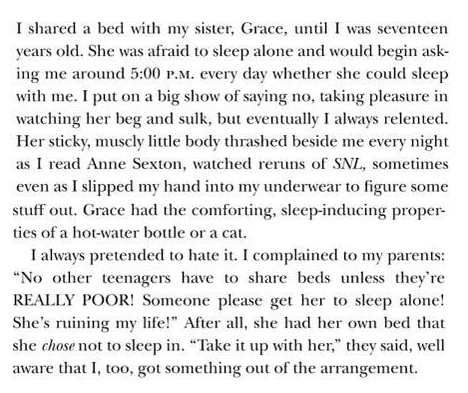

Ms. Dunham seems to describe engaging in self-pleasure during her teenage years while her pre-teen sister was sleeping beside her:

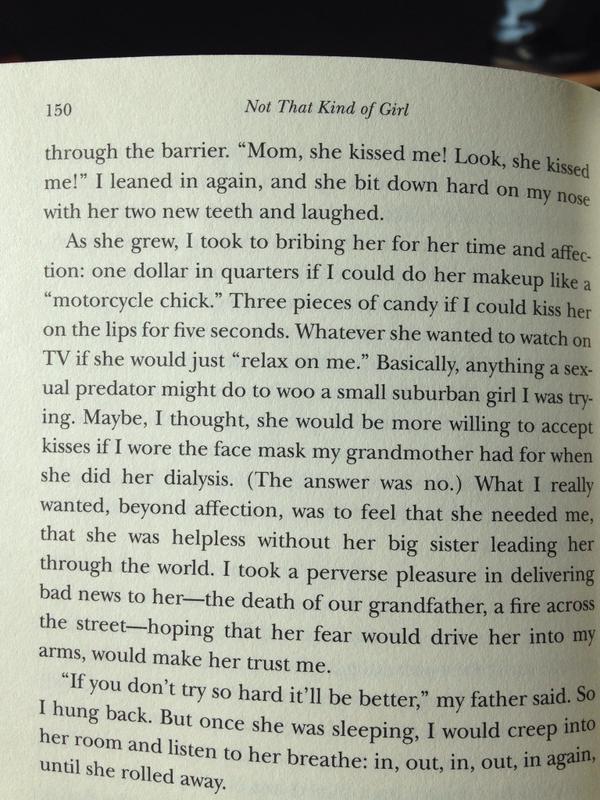

Ms. Dunham describes bribing her younger sister with candy in exchange for kisses on the lips:

Ms. Dunham describes bribing her younger sister with candy in exchange for kisses on the lips:

Perhaps most quoted was the passage in which Ms. Dunham describes an incident that occurred when she was seven:

With that bit of business out of the way, let’s devote some thought to the goals Ms. Dunham had in mind when committing these paragraphs to paper:

With that bit of business out of the way, let’s devote some thought to the goals Ms. Dunham had in mind when committing these paragraphs to paper:

- She was, no doubt, attempting to be honest with her audience. Her career seems to have been predicated on brutal honesty and openness, both physical and emotional. Not That Kind of Girl simply could not have been filled with cookie recipes.

- She was likely attempting to make further statement with regard to the female body and sexuality and societal perception of “normal” child development.

- Let’s face it: she was making sure that the book contained some titillating confessions. Ms. Dunham, like any other author, wanted her book to make a splash. I don’t think it’s fair to say that Ms. Dunham was expecting the level of pushback she received, but you can’t blame a writer for trying to gin up a bit of an argument around Pub Day.

A creative work, of course, must be evaluated on the basis of the creator’s goals. By those measures, Ms. Dunham was clearly quite successful. Perhaps too successful…

So did Ms. Dunham overshare? Ms. Dunham is part of the Millennial generation, a sea of people who have grown up in a world largely devoid of secrets. Many folks post EVERYTHING somewhere on the Internet: where they are getting their pizza, how little they like how they look in their mug shot, how funny the Wal-Mart shopper beside them is dressed.

It’s an interesting dilemma. Where is the line between honesty and oversharing? And how does that line compare when transplanted to the realm of creative nonfiction? Mary Karr is incredibly forthright when describing incidents that don’t exactly reflect her best self. Augusten Burroughs caught a lawsuit after publishing Running With Scissors; some of the other “characters” the book felt they were characterized as a “mentally unstable cult.” James Frey described his extreme and unbelievable behavior during…oh, nevermind.

Writers of creative nonfiction can’t stop writing about unsavory situations, sexual or otherwise. Not only do people love that material, but the events in question are deeply personal and don’t happen to everyone. Creative nonfictioneers must keep describing what sets their lives apart from those of others, even when the descriptions may make a reader uncomfortable.

On the other hand, these passages from Ms. Dunham’s book are pretty hardcore and relate to child sexuality…not exactly the world’s safest or most enjoyable topic. Would Ms. Dunham have lost some “honesty points” in her own mind had she struck those passages? How much does it matter that the author didn’t believe that these excerpts described, in the opinion of many, a pattern of sexual and psychological abuse?

Perhaps Ms. Dunham is embroiled in the controversy because she employed a joking and perhaps less-than-reverent tone in her piece. Now, I’m certainly not one to order a writer around; nor do I wish to order a colleague around. Perhaps the sentence “Basically, anything a sexual predator might do to woo a small suburban girl I was trying” was one step over the line. Instead of treating the subject with an appropriate seriousness, Ms. Dunham could come off as flippant to some.

If nothing else, Ms. Dunham has unintentionally started a dialogue that should not end with this little essay. What do you think? There is no absolute guideline with respect to what a writer must or should share, but where do you think the line should be painted?

Creative Nonfiction

GWS Essay, Lena Dunham, Roxane Gay