The last time I wrote about Amy Bloom, I pointed out that I had the pleasure of participating in a small-group workshop that she led when I was at Ohio State. Ms. Bloom was as fascinating as her work and brought a refreshing point of view to my grad school experience.

But now I am a little upset at her. There I was, all ready to work on the first draft of my next YA novel. My fountain pen (in this case, a Parker 21) was uncapped and ready to go. The journal in which I’ve been pounding out my draft was open to where I had left off the previous day. Then I made the fateful mistake of deciding to read the first few pages of Away, Ms. Bloom’s 2007 novel. As you may have guessed, I didn’t put the book aside after the first few pages. Ms. Bloom stole two and a half hours of writing time from me.

I’ll never get that time back, so the only thing I can do is figure out how Ms. Bloom convinced me to ignore my poor protagonist as he begged me to continue his tale.

Away is a sad and beautiful story about Lillian Leyb, a young woman who has escaped a Russian pogrom. Her family was not as lucky. She soon set sail for New York City, where she becomes the thin-pointed corner in an acute love triangle with an impresario in the Yiddish theater and his actor son. Upon hearing that her daughter Sophie may not be dead after all, Lillian sets off to find the little girl. Instead of taking the expensive trip over the Atlantic, Lillian decides to try to traverse North America to reach Russia via the Bering Strait. I don’t want to ruin any of the plot beyond that point…just read the book. You can buy it at your local indie bookstore or online. Ron Charles of the Washington Post liked the book as much as I did. Louisa Thomas of the New York Times Book Review is also a fan.

One of the facets of Away that I most admired was the way that Ms. Bloom was able to pack a vast journey worthy of Odysseus into only 240 pages. Charles Dickens and Victor Hugo loved to tell massive stories, but had trouble writing books under “brick” length. (I don’t mean to say that long books are a bad thing, of course; such tomes, I’m guessing, are just a harder sell in these times of Twitter.) Ms. Bloom recounts nearly two years of Lillian’s life in detail, but also manages to create compelling supporting characters, including an African-American prostitute, telegraph operators, inmates at a Canadian women’s reformatory and figures in the early twentieth-century Yiddish theater. How did she turn such a difficult trick?

Ms. Bloom catapulted her lonely character through a series of pairs and small groups. In a way, the book is a series of short stories centered upon Lillian’s interactions with an important character or two. For example, we see:

- Lillian and the relatives and friends who give her a home after she arrives in New York.

- Lillian and Reuben and Meyer Burstein, father/son theater team who use her in different ways.

- Lillian and Gumdrop, a prostitute in Seattle.

Ms. Bloom certainly gives Reuben and Meyer and Gumdrop their own moments in the sun and packs in full backstories for the characters, but these passages are brief and detract little focus from Lillian, the star of the novel. Why does this technique work in so splendid a manner? I believe it’s because the protagonist’s series of close relationships drive the plot perhaps more than the actual plot. In the hands of a lesser writer like me, the story would have been more about the things that Lillian did to fulfill her goal and the things that happened to her along the way. That’s okay…but Ms. Bloom’s use of relationship is much more powerful than simple plot points.

Think of it this way. Let’s pretend that Away followed a “plot point” structure in which the events are more important than any of the characters. (You know, like in a Transformers film.)

- Lillian arrives in New York.

- Lillian gets a job in the costuming department of a theater.

- Lillian gets a job as the mistress of an impresario and his son.

- Lillian finds out her daughter is alive.

- Lillian heads cross-country to find her.

Okay…okay…that’s fine, but Ms. Bloom is intelligent and knowing enough to think of the book differently:

- Lillian struggles to establish herself in America and to deal with the loss of her family.

- Lillian struggles through her emotional paralysis in the midst of her involvement in a very strange love triangle.

- Lillian struggles to decide what to do after the revelation that her daughter may be alive, even though the source may be unreliable.

- Lillian struggles with solitude (and sleeping in dark and confined spaces) to get cross-country in her effort to find her daughter.

See how much more powerful the story is when you think of it as a series of struggles the protagonist must overcome? Think about this principle the next time you outline a work.

Now, I do have a little bit of will power. I could have stopped reading and gotten back to writing my YA novel. But then Ms. Bloom just HAD to go and do something else that was really smart and allowed her to tell an epic story in a novel that one can read in a single sitting.

Think back to the Transformers movies. Do you actually care about what happens to any of the characters? Nah. You’re not supposed to care. In a novel like Les Miserables, Victor Hugo manages to make you care very deeply about even the most minor of characters. Every one of them has unique personalities; Hugo develops them such that you can build psychological profiles of just about everyone, including the Friends of the ABC. Shoot, I first read that novel fifteen years ago and I still think about Azelma Thenardier from time to time. (And most people don’t even know who she is because she’s not in the musical.)

Like I said, Hugo had hundreds of pages over which to unspool his narrative. Ms. Bloom chose not to avail herself of that luxury and was therefore charged with finding other ways to increase the potency and epic nature of the work. Instead of describing the fates of each character in traditional narrative, Ms. Bloom weaves a description of what will happen to them (usually) in the last bit of dramatic present in which they participate.

Check out this excerpt from page 72. Reuben, the rich Yiddish theater impresario, has just denied Lillian the (relatively) small bit of money that will get her across the Atlantic and that much closer to Sophia:

Reuben walks carelessly through the Goldfadn costume room when he gets back. He compliments Miss Morris. He picks up a blue button beside Lillian’s sewing machine as if he is tidying up, and he flirts with the plump, pretty girl who always sat behind Lillian. It has not occurred to Lillian or Reuben what her leaving will do to him, that he will lose most of his vision within a year and when he cannot bear to make his way with a cane and a helper, he will retreat to the house in Brooklyn, eat without appetite through the winter, and die in the spring, lying beside Esther [his wife] in their big four-poster bed.

See how gracefully the present and future are interwoven? If only real life were that simple and efficient. This manifestation of extreme narrative control cuts down on the book’s page count, but also keeps the reader and the narrative chugging along, just like the train that brought Lillian from New York to Seattle.

Yes, it will take me that much longer to finish my YA book because I spent time reading instead. So I’m a little cross that Ms. Bloom and Away stole precious writing time from me, but I’ll get over it, as reading the book helped me improve my own writing.

Novel

2007, Amy Bloom, GWS Thanks For Stealing My Writing Time, Random House

Writers are asked many general questions about their craft.

…”What is your overarching philosophy regarding the inherent power of fiction?”…”What IS-character-to you?”…”What is the position of place in your work?”…

These are great and important questions, but I’m really curious about the little things. In the “Hey, Why’d You Do That” series, I ask accomplished writers about some of the very small choices they made during the process of composition.

Katherine Riegel is a friendly woman and a good teacher. She’s also a co-editor at Sweet: A Literary Confection. Most of all, however, Ms. Riegel is a writer who loves creating poetry and creative nonfiction.

In November of 2014, Ms. Riegel published a powerful piece of creative nonfiction at Brevity. Go ahead; check out “Run Towards Each Other.” Then come back here and see why the author did what she did.

1) You begin “Run Towards Each Other” with the following two sentences:

“It is Thanksgiving, again. My smile is a weapon cutting off access to my grief-treasure.”

So…”grief-treasure” isn’t a real word. I even copied it into Microsoft Word to make sure. Then I looked on dictionary.com. Then I realized you must have made it up for some reason.

How did you decide to combine those two specific words? Why did you include the hyphen?

KR: Such an interesting question! I deliberately wanted to link those words in order to make sure the metaphor was clear. I imagined the smile/weapon protecting treasure—something precious, something coveted, something collected over time. So a stranger might see only the weapon, the defense—the smile. But the treasure being protected is actually grief. So it was layers of metaphor: smile=weapon, grief=treasure. In asking the reader to engage with complex metaphor, I didn’t want language itself to make understanding any more difficult. So I…bent language to make it do what I wanted. And I think the comparison of grief to treasure in particular is so unexpected, so out of the norm in terms of the ways we usually talk about grief, that I didn’t want the reader to be able to interpret it any other way.

2) The third paragraph is all one sentence. And there are en-dashes that split the sentence into three sections in addition to commas and everything else that makes up a sentence.

Why did you decide to combine all of those clauses? How did you make sure that the reader would know what you meant to say? What was the effect you hoped to create?

KR: Microsoft Word wasn’t happy with that sentence. (Though actually the 3rd paragraph is 2 two sentences, which itself is problematic because the 2nd “sentence” is technically two fragments separated by a dash.) In the first sentence of that paragraph, the dashes did what dashes are generally supposed to do, in that, if you took out the material inside the dash, the grammatical structure of the sentence, and its essential meaning, would be unaffected. Oh, and incidentally those were em dashes in my document; I think the formatting of the site turned them into en dashes. I wanted to put some description of my own smile into the piece, but I knew if I didn’t limit it that I could go on and on in the most unflattering ways about my own smile. This made it essential to keep the image short, tucked within a sentence. I also deliberately left out the “and” before “my new loves” because I wanted the three items in the list to be equal. Somehow adding “and” would make it feel like the last one, the “new loves,” was either more or less important than the other two. I intended the order to be more chronological than by importance.

I think also that this particular paragraph, reflecting my (the narrator’s) self after my mother’s death, is particularly fragmented. All the clauses, as you say, are both linked and separate, connected only tenuously through punctuation. The speaker, too, is just barely held together, and still doesn’t quite believe how or why she is. As for the 2nd sentence, where I get to write “me—me,” I confess I gave myself permission to do that because of some lines/line breaks in a Sharon Olds poem. It’s called “His Stillness” and the sentence reads like this:

At the

end of his life his life began

to wake in me.

She deliberately ended a line with a throwaway word—“the”—in order to get a line which begins with “end,” ends with “began,” and has “his life” repeated in the middle. I wasn’t breaking my mini-essay into lines (though I did when I first wrote it—shhh, don’t tell) but there was something really important about repeating that word “me.” The narrator doesn’t feel worthy of the support she’s gotten, so she must repeated the word “me” to persuade herself she matters, even as that words is followed by “insignificant.”

3) So, “toward” and “towards” are interchangeable, but “towards” has that extra Zzzzzzzzzzzz sound at the end. “Toward” has a nice, crisp consonanty ending.

Why did you use “towards?”

KR: I have to confess this may be just dialect. I grew up in Illinois with parents from DC and Pennsylvania who went to school in Vermont. When I take “accent quizzes,” it nearly always gets my accent wrong because of that. (I say “ca-ra-mel,” for example, not “car-mel.”) I guess, when I think about it, “towards” sounds more together-y to me. People are running towards each other—everyone is doing the action. A person would run toward a house, because the house wouldn’t be doing the action. Or maybe I’m completely full of it, and I’m a teacher, so I can come up with an answer even if I have to make it up. 🙂

4) I’m pretty sure Grammar Girl would tell you that you didn’t need that comma in the sentence, “It is Thanksgiving, again.”

How come you put that comma there?

RM: Oh, yes. Very important, and very deliberate. I wanted to emphasize “again.” It is inevitable, it keeps coming around even when you don’t want it to. Putting the comma there was to try to show the dread, to make the reader feel just how much the narrator didn’t want it to be Thanksgiving—again. Oh boy. Here we go.

5) And here’s the penultimate sentence:

“In the barn I will pull carrots out of my pockets and hold them flat on my palms.”

“In the barn” is a dependent clause that begins a sentence. All of those nerds who complain about grammar stuff might say that you shoulda put a comma after “In the barn.”What made you leave the comma out?

KR: Really interesting punctuation questions! I think language has a music to it, a rhythm. Grammar and punctuation rules are in place to help with clarity, but we all know many of them are arbitrary and some are based on the rules of Latin, which early English grammarians decided was the only “proper” language and so must be imitated. In this case, it’s clear what’s happening, and I heard the sentence in a particular way in my head. It wasn’t interrupted by a pause after “barn.” I’m one of those people who hears a voice very clearly in my head when I read; I don’t read my work aloud much during revision because it’s redundant. I heard this sentence as a whole, the image words like fence posts, regularly spaced: barn, carrots, pockets, flat, palms.

It’s odd to see how often I bend/break grammar and punctuation rules, when I emphasize clarity in both those areas as a teacher. I suppose I’m more concerned with syntax and its possibilities than with absolute rules. I want writing to be precise, in order to get across nuance and subtlety. That kind of precision requires a writer to make considered choices that sometimes break rules.

Katherine Riegel is the author of two books of poetry, What the Mouth Was Made For and Castaway. Her poems and essays have appeared in journals including Brevity, Crazyhorse, and The Rumpus. She is co-founder and poetry editor of Sweet: A Literary Confection, and teaches at the University of South Florida. Visit her at www.katherineriegel.com.

Creative Nonfiction

2014, Brevity, Katherine Riegel, Sweet: A Literary Confection, Why'd You Do That?

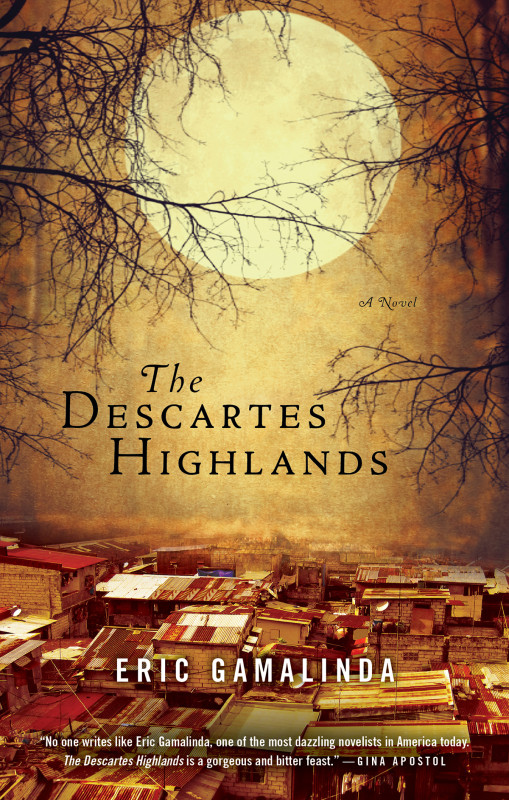

Friends, I had the honor of doing this interview with Eric Gamalinda, whose novel The Descartes Highlands is available from Akashic Books.

Mr. Gamalinda is a fantastic writer of prose, but he is also a film scholar who enjoys working cinematic images into his work. Film and prose are, of course, wildly different media. They are, however, quite similar in that they both allow you to tell a story and to describe characters and their surroundings.

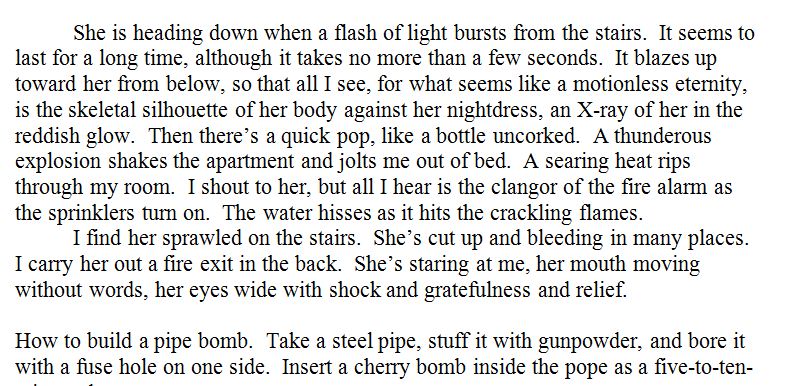

Approximately halfway through The Descartes Highlands, Mr. Gamalinda made use of an image from Andrei Tarkovsky’s Nostalghia. The following passage of the book reminded me of a still from another important film:

Doesn’t the description of the mother’s eyes remind you of Janet Leigh’s last scene in Psycho?

Doesn’t the description of the mother’s eyes remind you of Janet Leigh’s last scene in Psycho?

Filmmakers borrow from writers and vice versa all the time. Why not grab a pen and notebook?

1) What imagery might you steal from one of these scenes? How can you use language to match the power of the audio/visual representation of the same moment in time?

2) What would it look like if you adapted one of these scenes? How can letters, words, punctuation and white space be arranged in such a way that your paragraphs communicate the same emotions and plot as the film does?

The Omaha Beach invasion scene from Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan:

The cringeworthy, needleriffic scene from Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction:

The mind-blowing one-take Steadicam scene from Scorsese’s Goodfellas:

Oh my, I loved this movie. The fight scene from Blue is the Warmest Color/La Vie d’Adele:

The touching scene between two powerful women from Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon:

The heartbreaking final scene of Lean’s Brief Encounter:

Which powerful scenes have I failed to include? Want to share the poetry and/or prose that results from this exercise? The comments are right there waiting for you.

Exercises, Video

Akashic Books, Eric Gamalinda, GWS Exercise, The Descartes Highlands

Show Notes:

Enjoy this interview with Eric Gamalinda, author of The Descartes Highlands, a novel published by Akashic Books.

Find out more about Eric Gamalinda at his web site.

http://www.ericgamalinda.com/

Order your copy of his book from the publisher:

http://www.akashicbooks.com/catalog/the-descartes-highlands/

Mr. Gamalinda mentioned that he borrowed an image from Andrei Tarkovsky’s Nostalghia. Here is the trailer for the film; why not check it out?

Here is the passage from page 79 that I mentioned:

Here is the image from Psycho that the passage brought to my mind:

Visit my website: http://www.greatwriterssteal.com

Like me on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/GreatWritersSteal

Follow me on Twitter: @GreatWritersSte

Music: “BugaBlue,” Live At Blues Alley by U.S. Army Blues is licensed under a Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

http://freemusicarchive.org/music/US_Army_Blues/Live_At_Blues_Alley/

Many thanks to the Library of Congress for their beautiful public domain image:

http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/fsa2000055832/PP/

Novel, Video

Akashic Books, Eric Gamalinda, The Great Writers Steal Podcast