Title of Work and its Form: Impulse, novel

Author: Ellen Hopkins (on Twitter @EllenHopkinsYA)

Date of Work: 2007

Where the Work Can Be Found: Impulse can be found in independent bookstores everywhere. If you don’t know where to find the indie bookstore closest to you, IndieBound will be happy to point you in the right direction. The book can also be purchased online.

Bonuses: Ms. Hopkins’s site is extremely detailed and the author is very generous when it comes to communicating with her readers. Feel free to interact with other fans of Ms. Hopkins’s work at her Facebook page. Here is an interview that Ms. Hopkins gave to the Monster Librarian.

One of the things I love about YA literature is that fans are so enthused about what they read. Here is a fun video review of Impulse.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Narrative Structure

Discussion:

Tony, Vanessa and Conner are teenagers who are spending time in a psychiatric facility after unsuccessful attempts at suicide. Each of them tried different methods and had different reasons, but they are united in their grief, sadness and need for help. Slowly but surely, each of them reach mutual understanding and help each other address the problems that led them to such drastic measures.

If you listened to my interview with YA author Sarah Tregay, you heard her talk about how much she loves novels written in verse. Ms. Hopkins unspools the plot of Impulse through the course of hundreds of brief poems. Each poem is in first person and Ms. Hopkins cycles through each character every few poems.

Impulse is predicated on a high-concept conceit. Now, I love these kinds of projects-I’ve even completed a few of these works that play with narrative in extreme ways. The big problem when you undertake such a project is that you are making your job a little bit harder. Not only must you fulfill all of the standard obligations of the storyteller (plot, characterization), you must do so while remaining true to the unconventional structure that you’ve assumed. It’s hard enough to hold the reader’s hand through the course of a grand narrative packed with multiple protagonists…Ms. Hopkins challenged herself to take the reader on that same journey, but with her eyes closed!

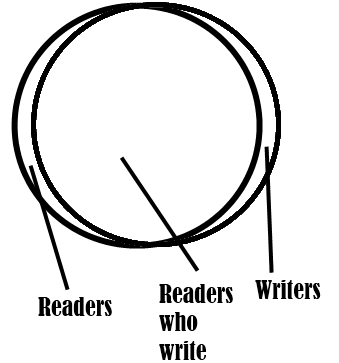

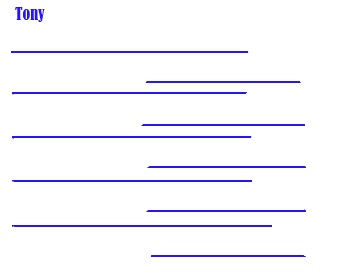

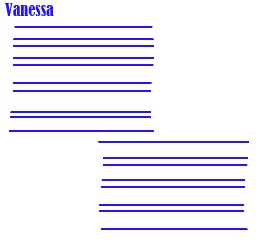

So how did Ms. Hopkins keep everything clear? Well, first of all, she was wise enough to make sure that each character composed poems of different and discernible style. With some exceptions-I’ll talk about those-each character composes poems thus:

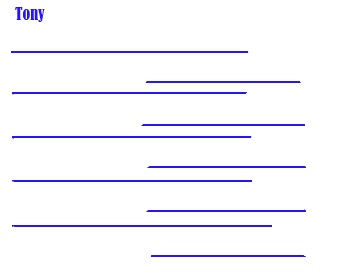

The lines of Tony’s poems generally alternate beginning at the left margin and a few tab stops in.

Vanessa’s poems generally consist of brief stanzas. The stanzas, not the lines, alternate between beginning at the left margin and a few tab stops in.

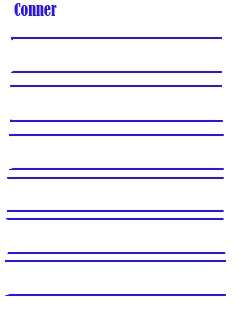

Conner’s poems are generally wrought from short lines, each of which begin on the left margin.

Why is this choice a very shrewd decision on Ms. Hopkins’ part? She gets a number of advantages:

- The reader can quickly (and perhaps subconsciously) understand which poem belongs to which character. Ms. Hopkins doesn’t have a narrator that can say, “Conner said,” so she must let us know who is speaking in another way. This is her way of doing so, in addition to including the character’s name before each section.

- The styles of poetry express the character. Conner begins the story as very strait-laced, so it makes sense that his lines are more “boring.” He SHOULDN’T have “funky” lines because that’s not the kind of character that he is. Tony’s lines are appropriate because he’s always vacillating, alternating between big thoughts in his life about facets of himself that he can’t understand. Vanessa is a little bit closer to self-understanding, but her poems must also express some confusion about herself.

- The patterns break down a little bit as the book goes on. This is a good thing. Why? These changes reflect the changes that are going on in the characters as they learn more about their problems and themselves.

It’s all a matter of “show, don’t tell.” (I know you’ve heard that writing advice before!) Instead of just typing out a TELL: “Hey! Tony understands his sexuality a little more completely now!,” Ms. Hopkins SHOWS you that Tony has become a little more comfortable with his past.

Ms. Hopkins is also careful to adhere to traditional story structure, but does so in an interesting way. I’ll explain. The story of Impulse does indeed follow Freytag’s Pyramid:

The story beats get more serious and more interesting…there’s a final climax…there’s a denouement and an establishment of the new status quo in the characters’ world…great. That’s what a writer is supposed to do. But Ms. Hopkins employs what I’ve decided to call Ken’s Character Onion:

I am aware that I cannot draw, but the point is that Conner, Tony and Vanessa resemble onions. How? They make us cry. Okay, I’m kidding. The characters resemble onions because they each have a number of layers that Ms. Hopkins peels back one by one. In Freytag’s Pyramid, each conflict in the story gets bigger and bigger. In Ken’s Character Onion, each revelation gets more and more dangerous. It’s not enough that the action is increasingly exciting; the stakes for each character must become more imposing.

I am aware that I cannot draw, but the point is that Conner, Tony and Vanessa resemble onions. How? They make us cry. Okay, I’m kidding. The characters resemble onions because they each have a number of layers that Ms. Hopkins peels back one by one. In Freytag’s Pyramid, each conflict in the story gets bigger and bigger. In Ken’s Character Onion, each revelation gets more and more dangerous. It’s not enough that the action is increasingly exciting; the stakes for each character must become more imposing.

Even better, Ken’s Character Onion adds suspense to a story. We care even more deeply about what will happen when we know that the author keeps raising the emotional stakes for his or her characters. Want a great example from the movie world? The 1999 Alexander Payne film Election (based upon the book by Tom Perrotta) begins with a dizzying, hilarious sequence of character-related details. We learn Tracy Flick is running for class president. She is extremely anal about the presentation of her clipboards. Mr. McAllister is put upon by the world; he must clean up the mess his coworkers made before he can put his lunch in the refrigerator. Tracy is a go-getter. Tracy had an affair with her teacher, Mr. McAllister’s friend, Dave Novotny. I know, it’s hard to understand without having seen the film. So go watch the film. Honestly, it’s nearly flawless and you’ll learn a ton.

Think of Freytag’s Pyramid and Ken’s Character Onion as parallel structures that keep a story interesting and a reader engaged. Just like Alexander Payne did in Election, Ms. Hopkins releases plot and character details with enough regularity to keep the reader chugging along.

The last thing we should learn from Impulse is something that I tend to think about whenever I read, write about…or write Young Adult fiction. I love the way that great YA literature deals with big, scary issues and treats its readers like…well…young adults instead of kids. Countless thousands of teenagers engage in the behaviors described in the book. They’re taken advantage of by teachers. They engage in cutting. They lash out sexually because of trauma they suffered in childhood. Perhaps it’s because I had a slightly challenging childhood and adolescence, but I never understood why a parent or authority figure would want to hide reality from a young person. We need to face facts: Teens think about sex on occasion. (Every five minutes.) Teens resist authority figures. Ms. Hopkins remains true to her readers by capturing the world as it is, not how the deluded believe it to be. And I’m willing to bet that Ms. Hopkins has received thousands of letters thanking her for the work she has done to improve lives through literature.

What Should We Steal?

- Allow yourself to work with a big conceit, but fulfill your obligations to your reader. You can write a story that violates every standard convention in the book…so long as you don’t leave your reader behind.

- Employ Ken’s Character Onion when you construct your characters. Little by little, your characters should have more depth and we should know more about their very serious concerns.

- Keep it real. No one is happy, for example, that some people are sexually abused. Depicting the struggle of such a person in story helps victims and non-victims alike to understand the depth of such a violation. (Which results in the empathy that prevents and punishes such sad events.)

Novel

Alexander Payne, Election, Ellen Hopkins, Impulse, Narrative Structure, Tom Perrotta, Young Adult

Friends, one of our greatest strengths is one of our greatest sadnesses. There are so many fantastic writers out there, so many beautiful books, so many powerful short stories and poems that we will never have time to read all of them. I know; there are worse problems to have. Just like you, I could walk into any bookstore in the English-speaking world and come out with an armful of tomes, some of which I would never get around to reading.

While we’ll never get around to everything on our lists, we can and should spread the word about lesser-known writers who mean a lot to us. We’ll never convert ALL of our friends, but it’s important to put as much attention as we can on cool people. (After all, that’s most of why I do this site.)

In that spirit, I ask…

Who is the most underrated writer around? Everyone knows about Joyce Carol Oates and T.C. Boyle and how great they are. Those writers, quite deservedly, get a constant stream of attention from powerful media outlets.

You know who should get more attention?

Mary Miller.

I love her stuff because she manages to be “literary” (whatever that means) and entertaining at the same time. Her stories are built from beautiful sentences, but her solid plots keep me reading because I want to know what happens to the well-drawn characters.

Now it’s your turn. Who should we know about and why?

Uncategorized

GWS Debate, Mary Miller

Say it with me: verisimilitude!

What a beautiful word. One of the big responsibilities we have as writers is to do as much as we can to breathe reality into our inherently fictional worlds. Fiction writers must keep the reader enthralled by the spells we cast on the page; nonfiction writers have an even greater need to maintain the reader’s trust that everything they say is true.

The problem? “Write what you know” only goes so far. If every writer stuck to that mantra literally, we would have no science fiction. I don’t want to live in that world. From time to time, we must exceed the limits of our expertise and must do so in ways that don’t out us as inexpert in the milieu of the story.

Mystery and crime fiction are packed with potential pitfalls. Most of us writers who compose in the genre aren’t police officers or authorities in ballistics. The overwhelming majority of us have never committed the kinds of crimes we write about. How can we write about stabbings and detectives and shootings without sounding like big phonies?

If you read Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, you already know some of the answers. If you don’t, get thee to their web site. You can also order single issues or subscriptions for Nook. (And for Kobo and Kindle.) One of the regular columns in EQMM is Bill Crider’s “Blog Bytes.” Each month, he tells you about worthwhile blogs in the crime/mystery field. (While you’re at it, check out Mr. Crider’s web site and his works.) The February issue features two links that are of particular interest to writers.

BJ Bourg is responsible for Righting Crime Fiction, a very detailed blog in which he tells you how to write about police procedures and firearms with verisimilitude. This is a necessity for folks like me who respect the power of guns, but don’t have any around. Mr. Bourg is a gentleman after my own heart; he will sometimes illustrate his points with examples from his own work.

Do you know the difference between an automatic and semi-automatic pistol? Do you know what that thingy at the back of a revolver is called and how it functions? Do you know the most efficient and safest way to load a revolver? I know I don’t. Mr. Bourg is also kind enough to include videos that show you what proper gun operation looks like.

Mr. Crider also tells us about Law and Fiction, a blog that is written by lawyer Leslie Ann Budewitz. Ms. Budewitz is also a crime fiction writer and author of the award-winning book Books, Crooks and Counselors, a tome dedicated to informing writers about the way the law really works. She’s trying to help you with the whole verisimilitude thing, friends.

The Law and Fiction blog is dedicated to educating you about the law and how it may apply to your characters. She is also kind enough to suggest possible subplots for you. You never know; you may read her blog and hear your Muse whisper in your ear. Ms. Budewitz seems like a very good egg. She likes puns and spends a lot of time helping other writers. (Hey! Like me!)

Web Site

Bill Crider, Crime Fiction, Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine, GWS Links for Writers

Title of Work and its Form: “Leap of Faith,” short story

Author: Brendan DuBois

Date of Work: 2015

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story made its debut the February 2015 issue of Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. The fine folks at that magazine have posted an excerpt of this equally fine story.

Bonuses: Here is an interview the author gave to WGBH. Here is his Smashwords page. Want to see Mr. DuBois discuss his work? Sure you do. (What he says is really inspiring!)

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Narrative Structure

Discussion:

I’m not quite sure why, but I devote a lot of GWS focus to “literary” fiction, for whatever that means. I’m guessing I’m not the only one, but I love spending time in the realm of “genre.” Or whatever that means. Mr. DuBois is a fantastic writer of mystery and suspense fiction and we should all be familiar with his work.

This particular story is a first-person piece whose protagonist is named Hank Kelleher. This is a frame story; the first couple pages take place when Hank is an adult. He climbs his way to the old quarry, a place that many people can understand. Isn’t there a similar place in every town? In this particular case, teens exercised their invincibility by drinking beers on the bank of a man-made lake and jumping into the water from three outcroppings of increasing height: Rook, Bishop and King. A police officer questions Hank, giving Mr. DuBois the excuse for Hank to tell the story of what happened when he was young. Hank’s father died when he was young, leaving him the “man of the family.” As a teen, Hank felt deficient in this duty because he couldn’t protect his little sister Kara from Dev Cullen, her abusive rich kid boyfriend. I don’t want to describe all of the fun out of the story. Suffice to say that “Leap of Faith” is tidy, entertaining and powerful.

One of the biggest reasons that “literary” writers should spend more time in the mystery sandbox is because writers like Mr. DuBois excel at creating plots that are utterly fictional, but seem perfectly natural in the refractory period after the story’s final blow. After setting up the frame-believe me, we’ll talk about that frame-Mr. DuBois wastes zero time introducing the story’s characters and central conflict:

The name’s Hank Kelleher, and I was seventeen that summer. And that’s when my fifteen-year-old sister Kara got into trouble. Not that kind of trouble, thank God, but over supper one night Mom had pressed my sister Kara about why she was dating Dev Cullen. “You know he’s just a bad sort,” Mom said, as she slapped dollops of mashed potatoes on the chipped white plates we used, next to the freshly made Hamburg steak. “He and his father Patrick and his damn uncle Blackie. Crooks, all of them. You stay away from him.”

The reader is not asked to wonder what is going on or to break out graph paper to chart the relationships between a thousand characters. Nope. Hank has a baby sister who is dating a bad young man. Everyone understands this situation, regardless of gender, race or age. Instead of wondering what is happening, we’re wondering something more specific: how will Hank save (or try to save) Kara from Dev.

If you are a dedicated GWS reader, you know that I love Freytag’s Pyramid and I love countdowns and other literal representations of its principles. The climax of the story takes place at the abandoned quarry, the place where teenagers go to…well, be teenagers. Mr. DuBois describes the quarry in the introduction of the story. There are three jumping platforms of increasing height: Rook, Bishop and King.

Why do I love the way Mr. DuBois contrived the geology of the story? The quarry’s topography is a literal match for Freytag’s Pyramid.

Like I said, I don’t want to give away too much, but the climax reaches increasing peaks of rising action on all three jumping platforms. The reader gets a moment of excitement…and then the calm as the splash recedes. We’re not wondering anything general about Hank’s motivations; we know he wants to protect his sister. Instead, our curiosity is focused upon a single, specific question: how is Hank’s final plan going to protect his sister and get Dev off of their case? Since the reader’s curiosity is so focused, Mr. DuBois can simply draw out the tension and put us on tenterhooks.

Like I said, I don’t want to give away too much, but the climax reaches increasing peaks of rising action on all three jumping platforms. The reader gets a moment of excitement…and then the calm as the splash recedes. We’re not wondering anything general about Hank’s motivations; we know he wants to protect his sister. Instead, our curiosity is focused upon a single, specific question: how is Hank’s final plan going to protect his sister and get Dev off of their case? Since the reader’s curiosity is so focused, Mr. DuBois can simply draw out the tension and put us on tenterhooks.

I wouldn’t be surprised if Mr. DuBois is also a fan of something I love a great deal: old-time radio dramas. One of my favorite programs is Suspense, which I suppose you could say was a bit like the Law & Order of its day (before the radio version of Dragnet premiered). Every week, the Man in Black would introduce a story. For half an hour, you would get thrills and chills and an ending that you didn’t see coming. (But an ending that makes sense in retrospect.) Here’s one of the best episodes ever, and one that was repeated live several times. It’s Agnes Moorehead in “Sorry, Wrong Number:”

Why should you listen to every episode of Suspense? Because the plots were usually constructed with flawless precision. The writers were expert at trading levels of power between characters. And the nature of radio required an awful lot of first-person narrators and frame stories. (You can’t exactly have long moments of silence on the radio and a third person narrator that zips around a lot would likely be confusing.) So go check out the vast beauty of old time radio.

Okay, let’s talk about that frame. At first, I was wondering why Mr. DuBois began with that present-day introduction and told the real narrative in flashback. I’m thinking about the suspense/crime stories I’ve written and I’m much more likely to begin with the sentences that kick off the flashback, “The name’s Hank Kelleher…” than a passage that is much calmer:

It took me three tries before I found the old dirt road, on the outskirts of the small Massachusetts town where I had grown up. The road twisted and turned, and ended up in a wide turnaround. There used to be a trail that went up a high slope, but now there was a chain-link fence blocking access. Every few feet there was a no trespassing sign, contrasting with trespassers will be prosecuted. I parked the rental car, got out, walked over to the fence.

Why did Mr. DuBois make the right choice? What can we learn? Putting the what-happens-to-Dev story in a frame allows Mr. DuBois to…

- Foreshadow that something significant happened in the quarry and in the Hank-Kara-Dev trio. After all, Old Hank knows what happened.

- Contrast the differences between the eighties and the present-day. The quarry is now filled up, being there attracts the attention of the police.

- Conclude with an ending frame that gives us a “happy ending” of sorts and tells us information to which we would not have access otherwise.

For more proof that Mr. DuBois made the right decision, think about the way the frame functions in the classic Twilight Zone episode, “To Serve Man.” Now, “Leap of Faith” is a very different story, but I think that the structures are similar.

What Should We Steal?

- Ensure that your plots invite your reader to wonder about increasingly specific questions. Think about LOST. At first, we wondered, “Where are they?” After five years, we were wondering, “What’s the Man in Black’s relationship to the John Locke who reappeared on The Island and how does he relate to the Heart of The Island?”

- Employ Freytag’s Pyramid in literal ways. The size of the dragons the hero must fight get larger for a reason…

- Consider trading an extra-punchy first sentence for greater depth and utility of narrative. Freytag’s Pyramid encourages us to employ a slow build in our plots; doing so is sometimes better than an explosive opening sentence or paragraph.

Short Story

2015, Brendan DuBois, Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine, Narrative Structure

A couple weeks ago, I was doing something that you should do. I was reading Dare Me, by Megan Abbott. The book is a fantastic…thriller/literary novel/New Adult novel that has gotten a great deal of well-deserved attention. Now, I was drawn in by Ms. Abbott’s beautifully drawn characters and her stellar use of language. I especially liked the way in which she added humor to leaven the sad story.

The prose, however, was sprinkled with little bits that drew the attention of my fountain pen nib. Ms. Abbott sprinkled in brand names from time to time. Take a look at some examples:

“I know she was out there in front of my house at 2:27, hunched over the steering wheel of her mother’s Miata.”

“Eyes on Tacy’s toned legs, which look like mini butterfingers, Beth shakes her head.”

“Flair strewn about, rolling empties of zero-carb rockstar and sugar-free monster, tampon wrappers and crushed goji berries.”

Ms. Abbott doesn’t include too many brand names in the book and I’m not entirely sure why some of them weren’t capitalized. (That’s not a criticism, really; Ms. Abbott is one of my favorite writers.)

Some writers embrace the inclusion of brand names in their work. After all, most of us refer to brand names all the time in our daily lives. We ask for a Pepsi instead of water. We order beer and wine by their brand names. When we don’t feel well, we ask our significant other to bring us a Tylenol or the bottle of Pepto Bismol. Brand names are part of our world, thanks to the fine work of all of the Don Drapers and Peggy Olsons out there. Including brand names in our fiction, then, could be seen as part of the responsibility we have to verisimilitude.

Brand names are also an opportunity for characterization and exposition. If you’re writing a story that takes place in the time when fountain pens were king, you could let the reader know that your character is well-off by giving him or her a Parker “51” instead of a Wearever Pennant. (The Pennant is a decent pen, but the “51” is sweet.)

However, this is a debate…

The use of brand names can also date a work. If memory serves, Stephen King includes a fair number of brand names in his work; young readers may stumble on what were commonplace references when Mr. King was in the heat of composition. Brand names could also be seen as a lazy shortcut that distracts from a work. You may decide for yourself that Ms. Abbott doesn’t gain anything by referring to Monster energy drink instead of just “energy drink.” You may believe that she violates Strunk and White’s first rule by including a word that could easily have been omitted. Deciding not to include brand names can also be a restriction that nudges us to increased creativity. Instead of a “Butterfinger,” could Ms. Abbott have included her own more powerful phrase?

What do you think? Do you use brand names in your work? When are they a good idea and when should you strike them with your red pencil?

Uncategorized

GWS Debate, Megan Abbott

Can we be honest? Most writers like attention and enjoy being part of a dedicated literary community. I am certainly one of these writers. The GWS Click Bait Controversy is designed to bring attention to an important issue that impacts us all. (And to bring attention to GWS.) The provocative title is designed to make you click, because that’s the only thing that seems to matter in today’s media landscape. (I thought about photoshopping a picture of a cat hugging a fish to get your attention.)

Here’s how the story started. I received an e-mail from the createwrite listserv for the Ohio State MFA program. The listserv is always full of new markets and with news of my colleages’ latest successes in the writing world. Someone sent out a call for submissions for a new online lit journal that was looking for material for its first issue. I’m always searching for new venues that might offer my work a good home, so I checked it out. [Note: I think I will omit the identity fo the mag in question for the time being.]

The journal’s web site is pretty standard; the vast majority of online mags operate in the same way. I clicked on the “SUBMIT PAGE” to learn about their editorial philosophy and…

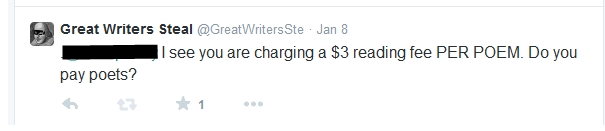

A “reading fee” of three dollars per poem?

Three dollars? Per poem?

For a brand-new online journal that doesn’t pay writers?

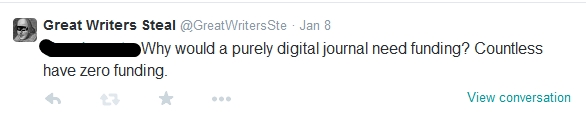

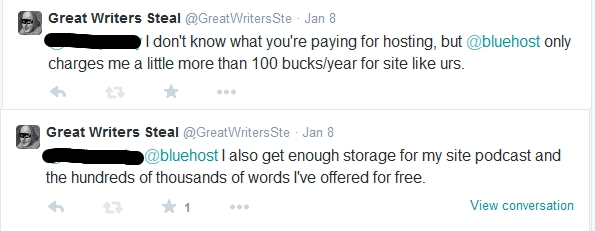

This policy seemed a little bit outrageous to me, so I tweeted the journal:

They replied back that they could not, as a brand-new journal, afford to pay poets. (You’ll see why I don’t have screen shots for their tweets.) They pointed out they had no funding.

They replied back that they could not, as a brand-new journal, afford to pay poets. (You’ll see why I don’t have screen shots for their tweets.) They pointed out they had no funding.

I replied:

Why don’t I have verbatim representations of their comments? This is why:

The exchange fired me up about a number of problems that we have in the world of literature, so I thought I would try to start a discussion in my far-too-polite manner. You are welcome to be less than polite in the comments.

The exchange fired me up about a number of problems that we have in the world of literature, so I thought I would try to start a discussion in my far-too-polite manner. You are welcome to be less than polite in the comments.

First of all, I understand why many journals charge submission (and not reading) fees. Journals, whether print or online or both, often subsist on a shoestring because we’ve lost a lot of readers for whatever reasons. Submission fees represent a welcome addition to the bottom line. Giving Submittable or Tell it Slant $3 for a short story submission isn’t too bad a deal, seeing as how postage for a snail mail package would cost nearly as much. (Sending two or three poems to a journal via USPS, of course, would cost far less than $3…) Further, journals only actually pull in half of the take from Submittable, as that company takes the other half.

While I’m clearly not opposed to all submission fees, I do think they are a growing problem in our field and are both a symptom and cause of the biggest challenges facing “literary writing.”

Perhaps most of all, submission fees privilege writers who can afford to pay them. Sure, $3 doesn’t seem like a lot, but that’s about twenty minutes of minimum-wage work. You submit a story five times and you’re up to $15, all so an editor (or intern) can read the first page or two of your story and click “reject.” Do we really want literary journals to be filled only with the work of people who have fat PayPal accounts?

Submission fees striate the field of writers in another way. Do awesome writers such as T.C. Boyle or Joyce Carol Oates pay submission fees when they send a story to the editors of a journal that charges fees? I’m guessing they don’t. I understand WHY they don’t pay, but does that make it fair?

I have paid submission fees in the past and will probably do so in the future according to a general philosophy, driven by my agreement with Harlan Ellison’s famous “Pay the Writer” rant. I get pretty upset with any publication that refuses to pay writers, the people who actually create the publication’s wares, but DO pay the editors, the publisher, the office chair company, the delivery company that brought the office chairs, the electric company, the office landlord, the water company, the copier company, the computer distributor, the paper clip supplier, the advertising agency, the cab company that takes employees home after late work nights and the restaurant that hosts the company holiday party.

I am more likely to pay the $3 if the journal is especially prestigious, if it pays, if it publishes in print, and if it is clear that no one is making any real money off of the journal. Everyone is welcome to make their own decisions, of course.

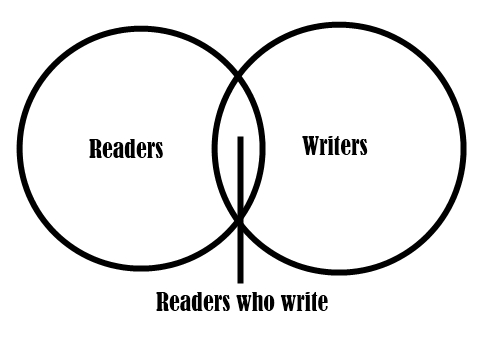

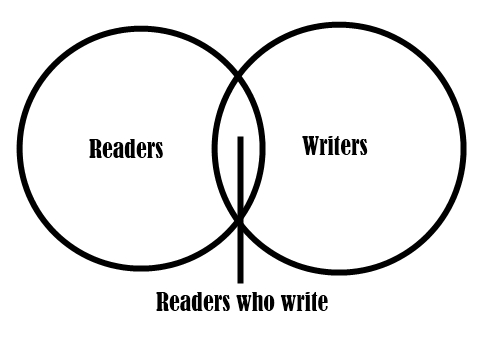

There are demographic changes in the cultural climate that I feel are a big problem. Here are some wholly unscientific Venn diagrams to describe my point. Think about fifty years ago, when our Literary Lions were roaring and people like Norman Mailer actually appeared on The Tonight Show. TV and radio were in full blossom, of course, but reading literature was much more important to the average person, even if it was simply a dime detective novel or a pulp science fiction magazine. Here’s my unscientific concept of what the world of literature looked like:

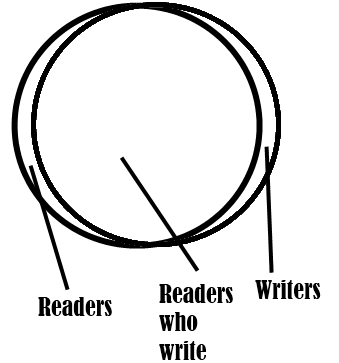

A large base of READERS supported writers in the past. Today, it seems as though every single person who reads short stories also wants to write and publish them. The landscape looks more like this:

A large base of READERS supported writers in the past. Today, it seems as though every single person who reads short stories also wants to write and publish them. The landscape looks more like this:

Am I suggesting anyone abandon all hopes of achieving greatness in the field of writing? Of course not. I am suggesting that it’s dangerous to increasingly rely upon those “readers who write” as sole support for any literary endeavor. We need to create NEW readers. We need to produce more work and more journals that will appeal to more people. We need to dismantle the delusion among many prospective readers that poetry must be impenetrable and that poets are deliberately trying to confuse. Submission fees are, in a way, an acknowledgement that the literary world is becoming ever more insular and can only gain support from those who are already intimately involved with the scene.

Am I suggesting anyone abandon all hopes of achieving greatness in the field of writing? Of course not. I am suggesting that it’s dangerous to increasingly rely upon those “readers who write” as sole support for any literary endeavor. We need to create NEW readers. We need to produce more work and more journals that will appeal to more people. We need to dismantle the delusion among many prospective readers that poetry must be impenetrable and that poets are deliberately trying to confuse. Submission fees are, in a way, an acknowledgement that the literary world is becoming ever more insular and can only gain support from those who are already intimately involved with the scene.

And the scene is indeed shrinking. An alarming number of people are simply unable to read literature. A Washington Post article cites Michael Gorman, president of the American Library Association and a librarian at California State University at Fresno, lamenting that “Only 31 percent of college graduates can read a complex book and extrapolate from it. That’s not saying much for the remainder.” Journals and publishers should be reaching out for support from the wider public, not digging in, hoping for a small sliver of a dwindling pie. Submission fees seem like a kind of admission that the work we are producing can’t garner a wide enough audience to be self-sustaining.

Am I advocating a literary world in which all books feature robots that transform into cars? Would I like every book to be the length of a dozen tweets with giant pictures of Kim Kardashian pointing to the words so people will read them? No. Perhaps we need to take a long look at the state of the literary community and figure out how we can become more relevant in mainstream culture.

Most importantly: what do you think? Leave a comment or interact on social media.

Uncategorized

GWS Click Bait Controversy

COFFEE SHOP (Early Morning) - I was supposed to be working on my next young adult novel. Its protagonist was whispering in my ear and I knew what he was about to do. I had just enough caffeine to get my brain going without making my body shake. Fountain pen: uncapped. Journal: open.

Then I thought I might read a little bit more of The Disreputable History of Frankie Landau-Banks, a book by E. Lockhart. (Ms. Lockhart is on Twitter @elockhart.) If you haven’t read the book, why not pick up a copy from your local independent bookstore or online?

Frankie Landau-Banks is a clever young woman who attends Alabaster Preparatory Academy, an expensive school in the Northeast. Like all people her age, she is trying to figure out who she is and her place in the world. Her father and sister attended Alabaster, and her freshman year wasn’t that bad…except for her relationship with Porter Welsch, who cheated on her. Frankie starts dating Matthew, a cute senior. All is well until Frankie gets curious and follows Matthew around, only to discover that he is part of Alabaster’s secret society. The dissembling puts a bit of a wedge between them; Frankie wants to be a part of the group! So she makes herself a member in her own way. I don’t want to ruin the whole book. Just go read it. (But don’t start the novel if you have any hopes of finishing your own.)

Ms. Lockhart had a big problem. Her story is packed with secrets all over the place. Frankie has secrets from Matthew and her father and her sister and from Alpha and from the head of the college and her roommate…that’s a lot of information to withhold! Writing the book was made even more complicated by the fact that Ms. Lockhart must figure out how much the reader should know and when they’re allowed to know it…even her narrator must keep secrets. But if the narrator keeps too many secrets, the reader will get bored and will throw the book across the room.

What to do?

Well, one reason I’m not cross with Ms. Lockhart for stealing my writing time is because she demonstrated a very interesting way of condensing a story’s exposition. (In case you don’t know, exposition is what we call the basic information about the protagonist and their setting. Exposition is all of the factual stuff we need to know before we can proceed with the story.)

Want to see a visual example of some graceful exposition? Sure, you do. Take a look at the opening sequence of any Bond movie. (Except for the first one and the last few.) The film starts with the blast of brass instruments and we see James Bond through the barrel of an assassin’s rifle. Without warning, Bond turns and fires and the barrel fills with blood and wobbles; the assassin is dead. See?

What makes this condensed exposition? We learn everything we need to know about Bond in less than a minute. People want to harm Bond. He has a target on his back. But Bond not only knows who is stalking him, but can draw first. And boy, is he a good shot. Even if you know nothing about Bond, you’re ready to go.

Ms. Lockhart, of course, had different problems. Frankie Landau-Banks is not yet as well-known as James Bond. Nor do readers know everything about her world. How to introduce everything the reader needs to get going without pumping out dozens of pages of boring description?

Ms. Lockhart begins the book with Frankie’s confession. Go ahead, check it out. It’s on Ms. Lockhart’s web site. We see lots of references to things we don’t know about. What’s the Night of a Thousand Dogs and the Canned Beet Rebellion? We don’t need to know. If you read the confession, here’s some of the exposition you get:

- The month and year.

- The setting of the book (Alabaster Prep)

- There are going to be “mal-doings” in the book. What does “mal-doings” mean? Frankie seems to like playing with language.

- There is something called the “Loyal Order of the Basset Hounds” at Alabaster.

- The Order did a bunch of things that are probably interesting or there wouldn’t be a book about them.

- Frankie was responsible for a lot of the mis-deeds.

- Porter Welsch seems a bit of a jerk…

Okay, I can’t type them all out-I have my own book to work on-but you get the point. Ms. Lockhart gives the narrator extreme power and allows it to present documentary evidence from the story to give us a handhold. When you read the rest of the book, you’ll see that the narrator does indeed zip around time and between characters and is pretty proactive when it needs to be. The narrator even presents an e-mail exchange or two that Frankie has with another character. We can learn about using the appropriate kind of narration to communicate the current plot point. If pretending to copy/paste e-mails into the book will tell that section of the story in a more efficient and interesting manner than traditional scenework, then so be it.

Ms. Lockhart clearly loves Frankie as much as the reader does. Frankie’s a fun young woman who does interesting things and thinks interesting thoughts. Groovy. But here’s the thing: characters who are always right and who always do and think the right things can be really boring. None of us are fallible, so it wouldn’t make sense for our protagonists to be infallible.

Approximately halfway through the book, Frankie is well into her investigation of the Bassets. She discusses the matter with her sister Zada. (Who is on the phone and a bit distracted.) One the reasons that Frankie is so preoccupied with the Bassets is that she’s not allowed to join because she’s female.

Let’s pause for a second: everyone reading this is a decent person, right? Sure. We can certainly see Frankie’s point. None of us likes to be told that we can’t do something. So when we read Frankie’s side of the story, we agree.

Then we hear sister Zada’s side. Zada points out that all the Bassets do is drink beer and engage in stupid pranks that waste time. She encourages Frankie to start her own group if she wants to be part of a secret society.

Now, it really doesn’t matter which sibling makes the better case. What matters that Ms. Lockhart gave us a good lesson: allow your protagonist, no matter how strong, to be wrong on occasion. Allow others to question his or her beliefs and actions. The world is not a black-and-white place, friends. There are countless shades of gray all around us. A story filled with too many absolutes is not one that can be easily believed.

Think of it this way. You’ve seen The Karate Kid, right? Not the remake, obviously. The good one. Daniel LaRussa is a fish out of water who feels alone…until he meets Mr. Miyagi and begins learning discipline and self-reliance from the martial arts. The ending of the film, of course, takes place at a karate tournament. We’re all rooting for Daniel-san to win! We want him to beat the Cobra Kai jerk! However, if the fight is too easy for Daniel, then we will lose interest. That’s why the Cobra Kai jerk cheats a little bit and hobbles Daniel, making it harder for him to fight.

We are happier when Daniel pulls through because writer Robert Mark Kamen and director John G. Avildsen give Daniel flaws and problems. Like Frankie, Daniel can be a little bit stubborn and judgmental. Neither character always does or says the right thing. We have these lapses, too; they’re what make us human…and isn’t that what we try to do in fiction? We try to create new worlds that feel real and are populated by real people.

So should I be upset that Ms. Lockhart took away some of my valuable writing time? Possibly. But wasn’t it worth it? I got to internalize some important lessons gleaned from her book and I had the pleasure to share them with you.

Novel

2008, E. Lockhart, Hyperion, Young Adult

Short Story

GWS Short Film

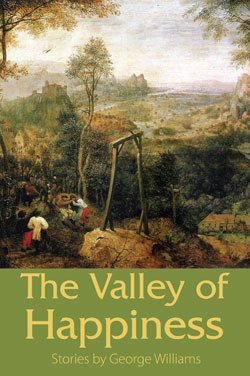

Friends, I had the honor of doing this interview with George Williams, a short story writer and novelist who teaches at Savannah College of Art and Design.

Mr. Williams is a very interesting man who had the great fortune to work with Donald Barthelme, whose writing marginally resembles the stories in The Valley of Happiness. If you don’t know Mr. Barthelme’s work, why not pick up one of the man’s books? Failing that, it looks as though a kind Internet citizen has secured permission to collect some works online. (Cool…look at one of Mr. Barthelme’s syllabi!)

(A slight tangent: one of the things in life for which I’m most grateful is that I can say that I worked with some all-time great writers and teachers: Ira Sukrungruang, Robert O’Connor, Lee K. Abbott, Lee Martin, Erin McGraw, Kathy Fagan, Michelle Herman… Writers and scholars are all part of a line of knowledge seekers that goes all the way back to Socrates and beyond. Mr. Williams is in Mr. Barthelme’s line. I know folks who are in Raymond Carver’s line. We should all take a moment to reflect upon how thankful we are for the teachers we’ve had along the way.)

One of the stories in Valley is titled “Televangelist at the Texas Motel.” The story is a single page; three paragraphs of relentless sentences and exclamation points. When I read the story, I made the note that the piece is “a kind of prayer.” During the course of our conversation, Mr. Williams pointed out that “Televangelist” began life as an exercise assigned by Mr. Barthelme, who told his students to write a rant.

Remember, friends, no word we write is ever a waste. Even when our lines are flabby and our characters flat, we’re building our skills and increasing the likelihood that the next piece will be better. In many cases, including this one, exercises can even be published. This story appeared in Gulf Coast in 1989.

Mr. Williams has published two collections, both with Raw Dog Screaming Press. Both volumes also feature jacket art created by great artists who also happen to work for free, seeing as how they’ve been dead for hundreds of years. The tone of The Valley of Happiness and its stories is set by “The Magpie on the Gallows,” a painting by Pieter Bruegel the Elder.

Mr. Williams admires the feeling of the painting. At first, you think that one of the men is being led to the gallows for a hanging. Then you realize that there is simply a party happening…in the same place where those folks witness executions.

For this exercise, I’m pretend-assigning you in Barthelme style to compose a rant based upon a classic (public domain) painting. What are some of the qualities of a rant?

- Extreme emotion. Rants are what happen when our reasonable rhetoric has been ignored.

- Brazen language. Subtlety doesn’t quite work for a rant.

- A subject worthy of the above. Did the drive-through worker forget to give you a third napkin? You’ll live. Confront a subject of real importance to the individual or the larger world.

Here are some examples. Feel free to download the images so you can see bigger versions.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s “At the Moulin Rouge, The Dance”

Edgar Degas’ “The Dance Class”

Caravaggio’s “Boy With a Basket of Fruit”

There’s plenty to rant about in these paintings. Are you pleased or angry that the all-male space seems to have been turned into a co-ed gathering? Can you believe what the ballerina with the green bow said about the one with the yellow bow? They’re supposed to be friends! And can you believe the lengths to which dieticians will go to try and make you add more fruits to your diet?!?!?

Those paintings don’t do anything for you? That’s fine. There are plenty more paintings where those came from. You can find 44,000 paintings here.

Want an example of an audio rant? Here’s playwright/comedian Lewis Black laying down some truth:

Good luck writing your own rants. You never know; you might produce a publishable piece of work! And keep in mind that you could always paste the result of your labor into a comment on this page. Who knows? Maybe I’ll publish your rant on its own page and write about what we can learn from you!

Exercises

Donald Barthelme, George Williams, Raw Dog Screaming

Show Notes:

Enjoy this interview with George Williams, author of The Valley of Happiness, a collection published by the fine people at Raw Dog Screaming Press.

Take a look at Mr. Williams’s Goodreads page:

https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/4875077.George_Williams

Order your copies of his Raw Dog Screaming books from the publisher:

http://rawdogscreaming.com/authors/george-williams/

Here is a text interview Mr. Williams granted to D. Harlan Williams:

http://www.dharlanwilson.com/dreampeople/issue35/interviewwilliams.html

Mr. Williams refers to a book about the Shakespeare Authorship question. He’s talking about James Shapiro’s excellent book, Contested Will:

http://www.theguardian.com/books/2010/mar/20/contested-will-who-wrote-shakespeare

Here’s “The Magpie on the Gallows,” the painting that Mr. Williams chose for the cover of his collection:

Like writing exercises? Here is one inspired by the conversation I had with Mr. Williams:

http://www.greatwriterssteal.com/2015/01/02/an-exercise-inspired-by-george-williams-author-of-the-valley-of-happiness/

Visit my website: http://www.greatwriterssteal.com

Like me on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/GreatWritersSteal

Follow me on Twitter: @GreatWritersSte

Music: “BugaBlue,” Live At Blues Alley by U.S. Army Blues is licensed under a Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

http://freemusicarchive.org/music/US_Army_Blues/Live_At_Blues_Alley/

Many thanks to the Library of Congress for their beautiful public domain images:

http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2012649048/ (Savannah during the Civil War era!)

http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/fsa1998006340/PP/ (Voters in 1940 North Carolina waiting to cast their ballots!)

Short Story Collection

2014, George Williams, Raw Dog Screaming

I am aware that I cannot draw, but the point is that Conner, Tony and Vanessa resemble onions. How? They make us cry. Okay, I’m kidding. The characters resemble onions because they each have a number of layers that Ms. Hopkins peels back one by one. In Freytag’s Pyramid, each conflict in the story gets bigger and bigger. In Ken’s Character Onion, each revelation gets more and more dangerous. It’s not enough that the action is increasingly exciting; the stakes for each character must become more imposing.

I am aware that I cannot draw, but the point is that Conner, Tony and Vanessa resemble onions. How? They make us cry. Okay, I’m kidding. The characters resemble onions because they each have a number of layers that Ms. Hopkins peels back one by one. In Freytag’s Pyramid, each conflict in the story gets bigger and bigger. In Ken’s Character Onion, each revelation gets more and more dangerous. It’s not enough that the action is increasingly exciting; the stakes for each character must become more imposing.