What Can We Steal From Ellen Hopkins’s Impulse?

Title of Work and its Form: Impulse, novel

Author: Ellen Hopkins (on Twitter @EllenHopkinsYA)

Date of Work: 2007

Where the Work Can Be Found: Impulse can be found in independent bookstores everywhere. If you don’t know where to find the indie bookstore closest to you, IndieBound will be happy to point you in the right direction. The book can also be purchased online.

Bonuses: Ms. Hopkins’s site is extremely detailed and the author is very generous when it comes to communicating with her readers. Feel free to interact with other fans of Ms. Hopkins’s work at her Facebook page. Here is an interview that Ms. Hopkins gave to the Monster Librarian.

One of the things I love about YA literature is that fans are so enthused about what they read. Here is a fun video review of Impulse.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Narrative Structure

Discussion:

Tony, Vanessa and Conner are teenagers who are spending time in a psychiatric facility after unsuccessful attempts at suicide. Each of them tried different methods and had different reasons, but they are united in their grief, sadness and need for help. Slowly but surely, each of them reach mutual understanding and help each other address the problems that led them to such drastic measures.

If you listened to my interview with YA author Sarah Tregay, you heard her talk about how much she loves novels written in verse. Ms. Hopkins unspools the plot of Impulse through the course of hundreds of brief poems. Each poem is in first person and Ms. Hopkins cycles through each character every few poems.

Impulse is predicated on a high-concept conceit. Now, I love these kinds of projects-I’ve even completed a few of these works that play with narrative in extreme ways. The big problem when you undertake such a project is that you are making your job a little bit harder. Not only must you fulfill all of the standard obligations of the storyteller (plot, characterization), you must do so while remaining true to the unconventional structure that you’ve assumed. It’s hard enough to hold the reader’s hand through the course of a grand narrative packed with multiple protagonists…Ms. Hopkins challenged herself to take the reader on that same journey, but with her eyes closed!

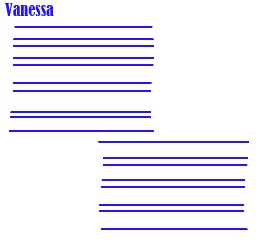

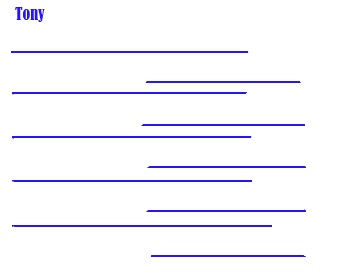

So how did Ms. Hopkins keep everything clear? Well, first of all, she was wise enough to make sure that each character composed poems of different and discernible style. With some exceptions-I’ll talk about those-each character composes poems thus:

The lines of Tony’s poems generally alternate beginning at the left margin and a few tab stops in.

Vanessa’s poems generally consist of brief stanzas. The stanzas, not the lines, alternate between beginning at the left margin and a few tab stops in.

Conner’s poems are generally wrought from short lines, each of which begin on the left margin.

Why is this choice a very shrewd decision on Ms. Hopkins’ part? She gets a number of advantages:

- The reader can quickly (and perhaps subconsciously) understand which poem belongs to which character. Ms. Hopkins doesn’t have a narrator that can say, “Conner said,” so she must let us know who is speaking in another way. This is her way of doing so, in addition to including the character’s name before each section.

- The styles of poetry express the character. Conner begins the story as very strait-laced, so it makes sense that his lines are more “boring.” He SHOULDN’T have “funky” lines because that’s not the kind of character that he is. Tony’s lines are appropriate because he’s always vacillating, alternating between big thoughts in his life about facets of himself that he can’t understand. Vanessa is a little bit closer to self-understanding, but her poems must also express some confusion about herself.

- The patterns break down a little bit as the book goes on. This is a good thing. Why? These changes reflect the changes that are going on in the characters as they learn more about their problems and themselves.

It’s all a matter of “show, don’t tell.” (I know you’ve heard that writing advice before!) Instead of just typing out a TELL: “Hey! Tony understands his sexuality a little more completely now!,” Ms. Hopkins SHOWS you that Tony has become a little more comfortable with his past.

Ms. Hopkins is also careful to adhere to traditional story structure, but does so in an interesting way. I’ll explain. The story of Impulse does indeed follow Freytag’s Pyramid:

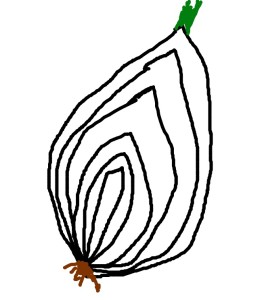

The story beats get more serious and more interesting…there’s a final climax…there’s a denouement and an establishment of the new status quo in the characters’ world…great. That’s what a writer is supposed to do. But Ms. Hopkins employs what I’ve decided to call Ken’s Character Onion:

I am aware that I cannot draw, but the point is that Conner, Tony and Vanessa resemble onions. How? They make us cry. Okay, I’m kidding. The characters resemble onions because they each have a number of layers that Ms. Hopkins peels back one by one. In Freytag’s Pyramid, each conflict in the story gets bigger and bigger. In Ken’s Character Onion, each revelation gets more and more dangerous. It’s not enough that the action is increasingly exciting; the stakes for each character must become more imposing.

I am aware that I cannot draw, but the point is that Conner, Tony and Vanessa resemble onions. How? They make us cry. Okay, I’m kidding. The characters resemble onions because they each have a number of layers that Ms. Hopkins peels back one by one. In Freytag’s Pyramid, each conflict in the story gets bigger and bigger. In Ken’s Character Onion, each revelation gets more and more dangerous. It’s not enough that the action is increasingly exciting; the stakes for each character must become more imposing.

Even better, Ken’s Character Onion adds suspense to a story. We care even more deeply about what will happen when we know that the author keeps raising the emotional stakes for his or her characters. Want a great example from the movie world? The 1999 Alexander Payne film Election (based upon the book by Tom Perrotta) begins with a dizzying, hilarious sequence of character-related details. We learn Tracy Flick is running for class president. She is extremely anal about the presentation of her clipboards. Mr. McAllister is put upon by the world; he must clean up the mess his coworkers made before he can put his lunch in the refrigerator. Tracy is a go-getter. Tracy had an affair with her teacher, Mr. McAllister’s friend, Dave Novotny. I know, it’s hard to understand without having seen the film. So go watch the film. Honestly, it’s nearly flawless and you’ll learn a ton.

Think of Freytag’s Pyramid and Ken’s Character Onion as parallel structures that keep a story interesting and a reader engaged. Just like Alexander Payne did in Election, Ms. Hopkins releases plot and character details with enough regularity to keep the reader chugging along.

The last thing we should learn from Impulse is something that I tend to think about whenever I read, write about…or write Young Adult fiction. I love the way that great YA literature deals with big, scary issues and treats its readers like…well…young adults instead of kids. Countless thousands of teenagers engage in the behaviors described in the book. They’re taken advantage of by teachers. They engage in cutting. They lash out sexually because of trauma they suffered in childhood. Perhaps it’s because I had a slightly challenging childhood and adolescence, but I never understood why a parent or authority figure would want to hide reality from a young person. We need to face facts: Teens think about sex on occasion. (Every five minutes.) Teens resist authority figures. Ms. Hopkins remains true to her readers by capturing the world as it is, not how the deluded believe it to be. And I’m willing to bet that Ms. Hopkins has received thousands of letters thanking her for the work she has done to improve lives through literature.

What Should We Steal?

- Allow yourself to work with a big conceit, but fulfill your obligations to your reader. You can write a story that violates every standard convention in the book…so long as you don’t leave your reader behind.

- Employ Ken’s Character Onion when you construct your characters. Little by little, your characters should have more depth and we should know more about their very serious concerns.

- Keep it real. No one is happy, for example, that some people are sexually abused. Depicting the struggle of such a person in story helps victims and non-victims alike to understand the depth of such a violation. (Which results in the empathy that prevents and punishes such sad events.)

Alexander Payne, Election, Ellen Hopkins, Impulse, Narrative Structure, Tom Perrotta, Young Adult

Leave a Reply