As anyone who knew me as a youngster can attest, I grew up in a haze of solitude and nerdiness. Not this nouveau nerdy, the kind where a person as attractive and as popular as Kaley Cuoco claims to be a huge geek because she likes The Big Bang Theory. I was honest-to-goodness, all-my-time-alone-in-my-room nerdy. Many of my early memories that have survived the defense mechanism wipe I’ve done on my brain relate to Star Trek in some way. I love The Next Generation and how “The Drumhead” taught me lessons we’d forget completely after 9/11 and still haven’t rediscovered. I loved reading the tie-in books and someday dreamed that I could write those books. (Those dreams have not come true.) I loved reading about the science fiction fandom that transpired before I was born, spending countless hours reading and re-reading the whitewashed Gene Roddenberry biography popular at the time.

As a young person, I had only a hint of what I would love most about Leonard Nimoy. There was no Internet, but the science fiction fan magazines often mentioned Mr. Nimoy’s side projects: his photography, his stage work, the films he directed. Mr. Nimoy possessed a quiet dignity that radiated through the screen. Behind that dignity, I think, was Mr. Nimoy’s ultimate truth: he loved human creativity and exercised his own in ways to which few of us can aspire.

We should all aspire to follow Mr. Nimoy’s lead and to manifest our creativity in the ways suggested by our Muses.

Mr. Nimoy did all of the following (and more) in his eighty-three years on Earth:

Acted on Broadway and in regional theaters.

Became a highly respected photographer who undertook a number of different projects examining some aspect of humanity or faith.

Published seven books of poetry and dabbled in putting some of that work online.

Directed feature films of the Star Trek and non-Star Trek variety.

Spent over 60 years in acting, from the near-infancy of television and the insanity of Hayes Code Hollywood to working on The Big Bang Theory and in video games.

Released music when he darn well felt like it.

Now, don’t feel bad if you don’t have the same kind of insanely broad ambitions. I am one of the people, however, who admires that Mr. Nimoy was curious about working in all kinds of forms and with all kinds of stories. I think it’s safe to say that Mr. Nimoy would be happy if contemplating his death inspired someone to write a song for the first time. Or to take up photography. Or to perform any creative act that they had previously avoided as a result of self-doubt or fear of what others would think.

Mr. Nimoy gave his audience what they wanted while remaining true to his artistic impulses.

In 1975, Star Trek was in syndication and its cast was in an interesting position: they were part of American pop culture, but weren’t exactly raking in the big bucks. The first Trek movie wouldn’t come out for a few years. It must have been an interesting and frustrating time for many of these folks. Mr. Nimoy published a book entitled I Am Not Spock. The book was not a repudiation of the role, but an affirmation of the author’s own identity.

Though he was frustrated by the typecasting he did receive, Mr. Nimoy understood that there are worse things than being beloved by millions of fans and respected by your professional acquaintances. Leonard Nimoy walked the line between art and commerce in way few have managed. What’s the balance between selling out artistically and selling enough to provide for oneself and one’s family? Mr. Nimoy gave us what we wanted: Mr. Spock, Three Men and a Baby, countless appearances at Trek conventions, In Search Of… He also gave us what we didn’t know he wanted: a Kabbalah-inspired photography project, Leonard-Nimoy-in-Equus, books of Nimoy poetry.

I worry that the “literary” community needs to do a better job at this balancing act. I hate the need for money as much as the next writer, but cash makes the world go around. Mr. Nimoy understood the audience principle and that if we fill enough seats with good work that is also popular, we can keep doing the good work that isn’t as commercially viable.

Leonard Nimoy made himself a part of every creative endeavor of which he was a part.

Like I said, I was a big-time nerd. I learned long ago that Mr. Nimoy accessed his Jewish roots when required to devise a Vulcan salute. The incredibly familiar hand gesture is derived from a blessing performed by kohanim. Don’t you find it beautiful that an ancient tradition will last in perpetuity, brought into the popular consciousness in an ambitious narrative that reflects mankind’s desire to explore the universe?

I don’t happen to be Jewish, but I love that Mr. Nimoy made use of what was familiar to him while helping to create a work of art that was not completely his own. How does your own work reflect who you are? Not necessarily in terms of easily defined categories or the obvious manners in which you identify yourself by group, but in the specificities of your past? Do you have a character who speaks like your long-dead great-grandmother? Have you written about shoemaking, the profession of an even more distant relative? What are we but a collection of stories; how do your long-buried and secret stories relate to the narrative of you and those you produce?

A life is like a garden…

Mr. Nimoy and I are very different artists; I’ve never had ambitions to act and I have no delusions that my voice could earn me a place behind a professional microphone. But I’ve always wanted to live the kind of life that Mr. Nimoy enjoyed: an existence packed to the brim with expression, filled with creative people and dedicated to examining the endless wonder to be found on Earth and beyond.

Television Program

Leonard Nimoy, Star Trek

Poems from Superstition Review, a brief interview in Agave Magazine.)

This (very) short prose work begins with a quotation from Louis Pasteur. Ms. Lawry uses Pasteur’s words as a jumping-off point for what appears to me to be a look at how Ms. Lawry believes her mind works and the kinds of thinking that result in inspiration. (The author may, of course, have a different idea about her piece and that’s okay, too.)

One of the things I like most about this piece is the implied suggestion that Ms. Lawry is making to the rest of us. If you’re like me, you like to play around and experiment with writing. Why not borrow Ms. Lawry’s idea and find some wise words from the past and create something new out of what you think they mean?

I’m not exactly the most “quote”-infatuated person. They just don’t inspire me on their own in the way they do for many people. That’s not to say that I don’t derive some kind of enlightenment and pleasure from reading inspirational extracts; I guess I just prefer understanding “quotes” in context. (I’m a storyteller and a plot person; I suppose this makes sense.) My proclivity certainly doesn’t prevent me from participating in the experiment I’m proposing. For example, one of my favorite sentences (and final sentences) is from Animal Farm:

The creatures outside looked from pig to man, and from man to pig, and from pig to man again; but already it was impossible to say which was which.

There are so many jumping-off points! I could write prose poem similar to Ms. Lawry’s about the thoughts that Orwell’s work evokes in me:

- The inability that many people have to recognize the real “bad guy” in situations.

- My feelings of being an outsider as I look upon others who have undeserved success. (I’m thinking Kardashians.)

- I really like pork chops and I wish I knew more about food science. The Maillard Reaction is the magic that creates the complicated flavor in browned meat. I also grew up without using salt, which somehow adds some magic to my current (and intermittent) culinary adventures.

See? Look how thinking about a “quote” can get some thoughts rolling around your head! What happens if you do the same?

I also like the way Ms. Lawry contradicts and gets in the way of Pasteur’s thought. By beginning with “I have no prepared mind,” Ms. Lawry is doing something that reminds me of my improv comedy roots. In a way, she’s “blocking” Pasteur. A “block” is when a performer says NO to something a scenemate has said. Blocks are (usually) killers because they stop the scene.

Bob: Hey, look at this beautiful dog I found!

Sally: That’s not a dog. It’s an elephant.

See how Sally messed up the scene? Now the audience thinks Bob has been walking around with an elephant in his arms. Everything has screeched to a halt. Sad. When you’re working with other people, particularly in an endeavor such as improv, you just can’t block in this manner. See how beautiful and creative people can be when they say “yes, and” instead of “no?”

But guess what…writing is a solitary pursuit and you can do whatever you like! Further, your characters will say or do anything you want, so blocks can be useful in creating a number of dramatic effects. Why not employ blocks to create drama and to establish character?

Have you seen Breaking Bad? If not, what are you waiting for? Go watch it NOW.

Okay, you’re back. Here are some examples from Breaking Bad that illustrate how blocking results in high-wire tension.

Remember when Skyler told Walt to go to the police and confess that he’s a drug king? Walt says no. Skyler tells Walt he’s in danger. Walt uncorks a crackerjack monologue:

That’s right…Walt is the one who knocks.

The whole point of Breaking Bad is to chronicle the moral evolution and tragic downfall of Walter White. Gus Fring asks Walt to serve as his meth chef in a Superlab. Walt will have all of the cool scientific equipment he needs to make the purest meth possible. (You have to admire Walt’s dedication to chemistry…) How does Walt respond to the request? He says no.

Arguments and discussions need some conflict and that sometimes requires characters to contradict each other. In this case, Gus is forced to persuade Walt to join him:

Think about a scene you’re building or a poem you’re working on. What if one character says “no?” What if there’s some unexpected internal or external opposition to the idea you’re expressing? Experiment with blocking to see if you can add unexpected power to your work.

Exercises, Short Story

Breaking Bad, elsewhere, Mercedes Lawry

Interview with Shimmer, From Strange Horizons: “The Serial Killer’s Astronaut Daughter”

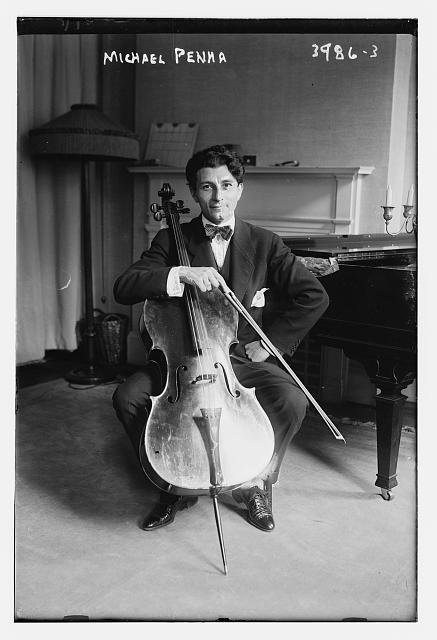

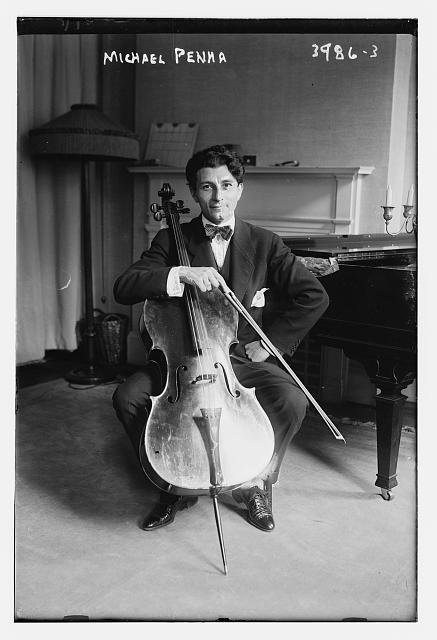

I’ve written before about the challenges posed by the popularization of short short fiction. As I pointed out then, there’s nothing inherently inferior about any medium. Genres and forms are like tools; they have advantages and disadvantages that shape the end result. “Requiem, for Solo Cello” clocks in at 1170 words , so it’s not the shortest of short stories, but I think that Ms. Walters’s poetic piece helps to illuminate some important issues.

First of all, I know the length of the story because the fine people at Apex Magazine include the word count with each story. Like I said: benefits and drawbacks. On one hand, I guess it is helpful to know that the story is not a 50,000-word novella. (Even though you could tell such a thing from the length of the web page.) Perhaps you’re going to bed and checking out the latest issue of Apex on an e-reader and you don’t want to start a long story that you can’t finish before you doze off. Okay, cool. On the other hand, do we really need such information? Should word count be one of the criteria by which we compose our reading list? As literature becomes an increasingly digital endeavor, I’ve really tried to make a conscious effort to read for the “right reasons.” (Word count is not usually a top priority, of course.) Am I the only one who has such a plan? Should I be?

Ms. Walters has broken her story into six sections, each of which contributes to a first person narrative about an unnamed woman who had an intense crush on a cellist. I use the past tense because of what happens in the story; the cellist and the narrator turn out to be incompatible lovers, but that doesn’t mean the affair wasn’t meaningful. The point of the story, it seemed to me, is that the narrator learned how to play her own instrument and to make her own music in the wake of heartbreak: a lesson that applies to all of us at one time or another.

“Requiem, for Solo Cello” illustrates how to solve one of the problems with short short stories. Ms. Walters (I’m guessing) knew that she was writing a relatively short piece and that her idea would not justify reams of page space. That’s fine; that’s why she created a story that fit the narrative in her head. How did she do so?

- She chose the right slice of story from the narrator’s life. This is the story of how she fell in a kind of love with the cellist and fell out love almost as quickly. Much more has happened in the narrator’s life, to be sure, but none of that matters, particularly when you only have 1200 words.

- She adopted a poetic diction and largely refrained from scenework. There’s no dialogue in the piece and the past-tense scenes consist predominantly of images released in pretty language.

- Perhaps most importantly, Ms. Walters’s story makes extensive use of an extended metaphor. You can’t cram a spy novel into 1200 words like Lady Gaga trying to cram all of her outfits into a single suitcase. You can, however, reduce the importance of the narrative itself and transfer that importance to an extended metaphor. Ms. Walters compares bodies to musical instruments; string instruments are perfect for such a metaphor. Not only do they resemble humans in shape (let’s keep it real, cellos have a very feminine shape), but they are also made from organic materials and are often shaped by human hands. See how there’s something beautiful and human about the cello?

Ms. Walters approaches the human/string instrument from a wide range of angles. We should follow her example and spend some time researching our extended metaphors. Here are some details that Ms. Walters works into her piece:

- Pieces often played by the cello

- The posture of the cellist and what it resembles.

- The beautiful “music” words, including glissando

- Specifics about the construction of the cello, including the materials used by luthiers

- Parts of the cello that resemble those of a human, including the neck and the “strings” that keep us together.

Whenever we construct a piece that makes use of an extended metaphor, we should sit down and just fill a few pages with all of the words and ideas related to the subject. We may not use everything we jot down, but that brainstorming work gives us more options and suggest opportunities upon which we may not otherwise capitalize.

To some extent, the piece succeeds because Ms. Walters doesn’t try to do too much with “Requiem, for Solo Cello.” We should admire the way she contrived the narrative to take advantage of the short short form and the skill with which she boosted the power of the metaphor to compensate for the requisite thinness of the plot.

Uncategorized

Apex Magazine, Damien Angelica Walters

Friends, FJ Contreras is an interesting gentleman. Please check out Mexican Driving, his cultural criticism/writing craft blog. You will also find some of his work at Hades United. Mr. Contreras is a writer and scholar and you would do well to follow him at @mexicandriving.

Today, Mr. Contreras gives us a look at what we can learn from “Fifteen Million Credits,” a beautiful episode of Black Mirror, a BBC anthology science fiction show. If you have not yet checked it out on Netflix, I advise you to do so soon.

Distance.

When truth is delivered unadorned, not only can it be deemed an attack, but it also makes an enemy of the messenger. The shades of the dismissal might vary in tone, but in the best of cases, the audience will judge it in bad taste, as in, Who in the hell does he think he is? It’s understandable. People don’t like to carve time out of their busy schedules to get punched in the ego. For this reason, science fiction allows writers to create a space between the criticism they want to exercise and the audience. See, by visiting a world far, far away, audiences get to feel like they’re evaluating the standards of a new reality, whereas in fact they’re judging their own.

But the distance created is a mere façade, because in no story, regardless of how weird, the elements in play belong to another world. That’s impossible. Wally the robot is a story about love, isolation and the dangers of consumerism-human love, isolation, and consumerism, that is. Even if we could think like a dolphin, a cat, or an alien, we only care about what’s human. In Star Wars, for example, when Darth Vader goes to war, notice how the militarized drag of the Empire marches down against the multicultural and colorful rebellion. The British Empire vs. America, perhaps? The rigid establishment from post-WWII America vs. the counterculture phenomenon of the 60s and the 70s? In one of the funniest bits of the opening bar scene from Episode IV, all sorts of aliens listen to jazz and fool around as they get drunk. It’s funny because they look ridiculous, but so do people when inebriated. If we were to find our escapades onscreen as everybody laughs, the humiliation would override our ability to reflect upon our vices.

And jazz, really? Jazz is not even in the Top 10 musical styles that will make it to 2050, much less transcend into a dystopian era.

The world of “Fifteen Million Merits,” on the surface, seems to be another planet, another time. Here, people never leave the building they inhabit. They sleep in cubbyholes, and every wall, even the ceiling, is a TV screen. The programming is controlled by a faceless entity, and it offers a number of lowbrow shows, which range from singing competitions, to fat people being humiliated, to pornography. Everyday activities are constantly interrupted by the same advertisements, which are unavoidable, because the act of shutting one’s eyes forces the screens to freeze, an alarm to blare, and the threats of a stiff penalty to flash. Everyone must cycle on stationary bikes that power the building. The more they cycle, the more merits they earn. This world is somber and monotonous, so there’s not much to spend those merits on, except for an apple or a sugary treat, which ironically, is transformed into the energy used to cycle. However, every person has an avatar which grants them a second life. These avatars live online and get to attend the singing competitions, where they cheer and vote. The avatars can also be clothed and accessorized for a price, of course, and that’s where those merits go. There’s another way out, and that is to spend 15,000,000 merits for a chance to sing/dance on TV. If picked, the next step is to face a panel of three self-involved judges, and then to sing/dance. Only the best one, of course, can become a star. The good ones are offered the choice between going back to the bike, or a reduced role in one of the other second-tier shows, or if pretty enough, in pornography.

How is this distance turned into a pungent social critique?

- The references to American Idol and other reality shows are evident. They reveal our desire a) to stand out, b) to be admired by a shitload of people, c) to receive better privileges than the rest, and d) to flaunt those privileges. Or worse, e) to cheer for those egotistical idiots.

- In our world, education is the way for the lower and middle classes to climb out of the bike, but in this episode there’s no middle ground. You’re either a star or a follower. This is not a crazy notion, as the middle class in some of the few first-world countries is thinning out. Politically speaking, the center is disappearing as well.

- Clearly, the personalities we have created through social media demand most of our time. And have you noticed how much time people spend on their phones, even when surrounded by their closest friends? In order to be cool, these versions of ourselves, these avatars, need to be groomed carefully and often.

- There’s a risk that we’ll be enslaved if we keep giving so much of our liberties and personal information to this monstrous corporations. As they continue to absorb each other, Leviathan will defeat the rest and will become more powerful than governments themselves. With no competition, the remaining monster will have no need to serve its citizens with variety and authenticity. So imagine what it’ll be like to be forced to watch the same four commercials all day and all night. It would be like watching Hulu-wait a minute…

- Now imagine life is either Coke, Diet Coke, or Cherry Coke. That means we’d be working for that brand. Also, we’d be returning them their money, as their products are the only ones available. You don’t want Coke because it slowly dissolves the lining in your stomach? Drink Dasani water, made by Coke. You don’t like it because it’s brown, wormy, and gives you diarrhea? Sorry. That’s all there is, so drink your fucking Coke.

- The warnings are not hard to read: large corporations today, as the grow, raise their prices, decrease customer support, push product through ubiquitous marketing campaigns, and create a dog-eat-dog environment for their employees. The more they expand over the globe, the more they control the public’s choices. If I say sports, the first thing that comes to mind is ESPN. As much as I don’t like ESPN, I can’t get the brand out of my head. Where else can I go if the quality and coverage of the competition’s product pales in comparison?

- I write what I find interesting and important, not what I think people will like. But what if I were coerced to reverse my strategy? What if James Joyce, instead of writing Ulysses, had no other option but to produce Fifty Shades Of Grey? What if the doctor begins to prescribe the medication patients want and not the one they need? What if artists paint what most people want to see, and musicians sing what the majority want to hear? In other words, what if we live as trend-setters and trend-followers and not as pioneers and innovators? Would we find that world plentiful? The irony is that if we were to live in the latter, we wouldn’t have the ability to tell the difference. Thus, it is thanks to science fiction and the distance it creates between its reality and ours that we can evaluate how close we are to the despotic terrors of “Fifteen Million Merits.”

Uncategorized

For better and worse, the Internet is here to stay. (Yes, I borrowed that sentence from 1995.) It’s still possible for writers to avoid the Information Superhighway completely, of course. Unless I’m mistaken, Cormac McCarthy is still 100% old school. (And aren’t we jealous?)

For the rest of us, however, it’s probably a good idea to have some kind of digital presence. Why?

- Readers want to be able to find your work! A web site makes this easy.

- Having a web site and connected social media accounts allow you to “network” and make friends with other writers.

- Many publishers appreciate writers who communicate with readers

- Having a web site lets you post whatever you like, whenever you like.

Through the course of writing way too many essays for Great Writers Steal, I’ve come into contact with a wide variety of writer sites. Each of them are different because each of them are designed to express the identity of a different writer. You need to decide what your Internet presence will look like, just as you call all the shots when it comes to your short stories and poems and plays.

Web sites offer near-infinite opportunities for customization, even if you’re not an expert in HTML or Flash. (I’m certainly not.) You need to decide for yourself what your site will look like and what it will do, but here are some basic types of sites that I have seen and how they can spread the gospel of you.

The Basic Informational Site

This kind of site is a simple placeholder for information. You don’t do much with the site, but your readers learn about you and your work.

I put together a site like this for the great Lee K. Abbott (with his consent, of course). I popped all the information I could find into a simple WordPress site and now all of the Lee K. Abbott fans out there have a one-stop Lee K. shop. Why is this kind of site perfect for him? While he could do much more Internet stuff if he wanted to, I don’t believe he feels like it. And that’s fine. The site cost zero dollars to produce and will be around forever.

What will you find on the basic informational site? Take a look:

Nothing fancy or pretentious, but plenty of meaning, just like Mr. Abbott.

The Basic Creative Outlet and Marketing Opportunity

This kind of web site is a little more complicated than the first. You get all of the basic information, but you also get to play a little. An example of this kind of web page is the official site of Leigh Allison Wilson. I helped Ms. Wilson put the site together, but she maintains it and does whatever she likes. And isn’t that the point? Take a look:

A list of Ms. Wilson’s books? Check. A list of her short stories and where you can find them? Check. Links to work of hers that is available on the ‘Net? Check.

Ms. Wilson is also kind enough to add blog posts or short shorts every so often, creating an incentive for visitors to drop by multiple times. Periodic updates may also inform your readers about what is happening in your life or your work.

The Immersive Reader Experience

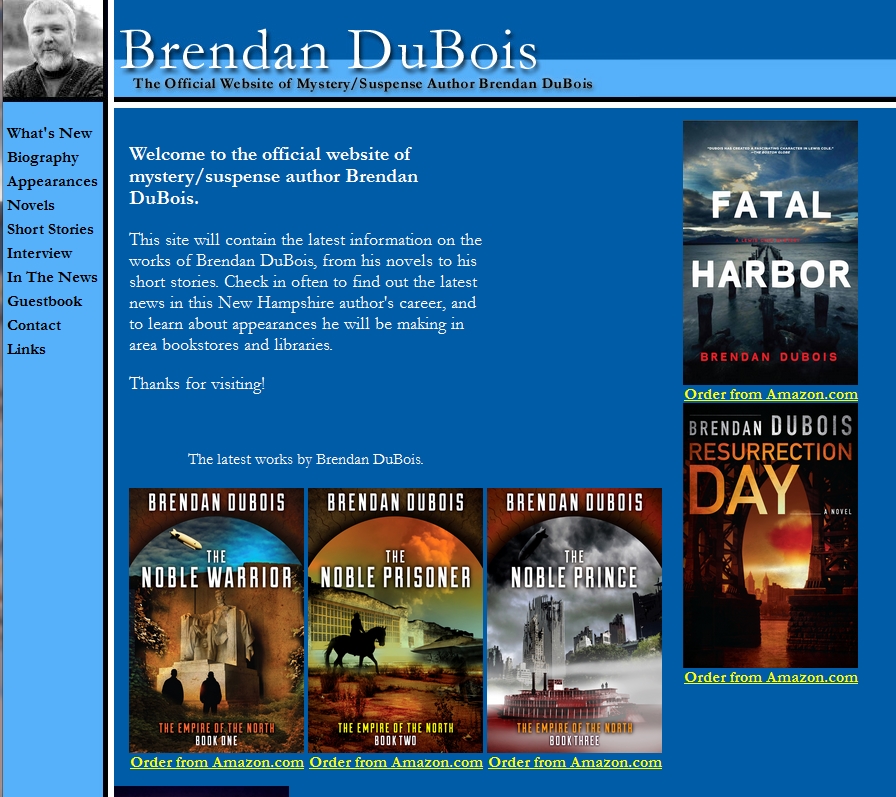

This kind of web site is a PR person’s dream. A writer such as Brendan DuBois devotes some of his valuable time to chronicling his available work. He also makes it as easy as possible for you to find what he’s done and even to communicate with him.

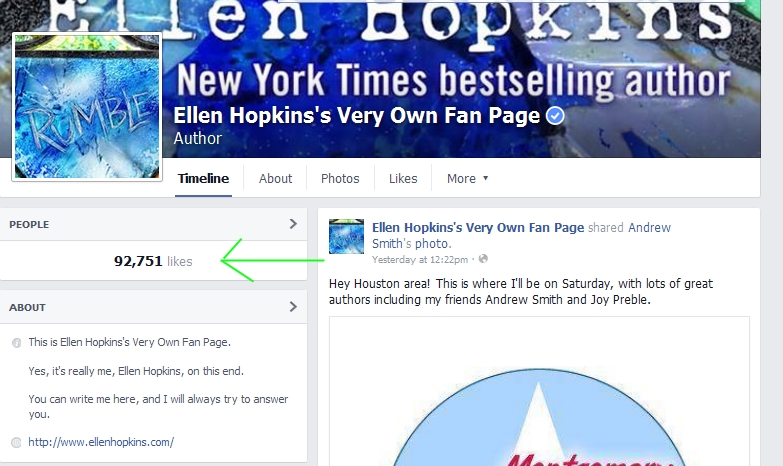

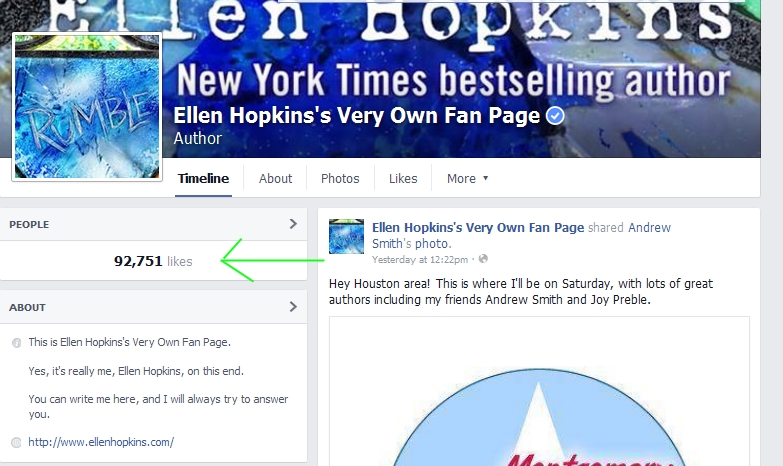

Social media is also part of the immersive reader experience. Novelist Ellen Hopkins has more than 92,000 Facebook friends! The page allows her to tell fans about her new work and her readings and even allows her to interact with them in relatively time-efficient ways.

The Creative Endeavor

For better or worse, Great Writers Steal is this kind of writer site. I offer people what I hope is a valuable resource (for free!). In exchange, I hope people enjoy what I do and that they might be more likely to check out my short stories and poems and so on.

Another example of a writer who offers this kind of site is F.J. Contreras. His blog, Mexican Driving, offers you cultural criticism and his thoughts on literature. Another of his efforts, Hades United, compiles a lot of his work that wasn’t published elsewhere.

Why create a site like this? I suppose the reason must be personal. I truly love discussing literature with the people who are nice enough to visit my site and I love that I have a creative outlet for efforts that may not fit in anywhere else. Unfortunately, my creativity has always lacked a laserbeam focus; I have a million things I want to say and do and that means that I’m not going to be able to say and do them all. But a site like Great Writers Steal allows me to get closer to my ultimate goals. (I think.)

Uncategorized

Friends, I spend a lot of time hating on the Internet and resenting the way that the contemporary media environment has narrowed thought and turned American journalism into an endless series of Kim Kardashian pictures and speculation as to how the Charlie Hebdo massacre will affect your favorite YouTube stars.

You know what? I have occasion to give the Internet some well-deserved props. I’m fixing up a draft of a mystery/crime story and I wanted to confirm some details and double-check everything…you know, overall verisimilitude stuff. Don’t we live in an amazing time? I can virtually walk the streets of Mexican coastal town of Sayulita:

https://www.google.com/maps/place/SAYULiTA+CAFE+CASA+del+CHILE+RELLENO/@20.86935,-105.439971,3a,75y,356.48h,90.88t/data=!3m4!1e1!3m2!1suw9KYfx9ikChm4nRsIH8lw!2e0!4m2!3m1!1s0x0000000000000000:0xd8abd217a1160632!6m1!1e1

I can watch (extremely positive) video of what Sayulita is like.

I can even drop in on a wedding that took place in Sayulita!

And since it’s a crime story, I can keep tabs on drug crimes and murders in Nayarit.

So while I deeply resent what the Internet has done to so many facets of our literary world, I can’t help but be grateful for some of the good that the World Wide Web has brought us.

How has the Internet helped you with your writing?

Uncategorized

GWS Debate