Philip Roth’s Everyman: Analepsis and Adverbs

Everyman, by Philip Roth

New York Times review, first chapter, Fresh Air interview in which Mr. Roth discusses the book.

Buy the book from your local indie.

How do you condense a faithful representation of a man’s life into 182 pages of prose? Don’t we like to think that we’re so complicated that the task is impossible? I suppose that the conceit that drives Everyman is an unreachable goal; how do we explain the thousand sins we commit? How can we share the thousand joys of our lives with strangers?

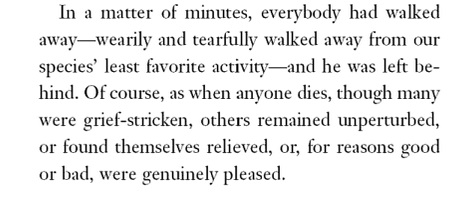

Mr. Roth, of course, is skillful enough that his ambition doesn’t exceed his ability. Everyman‘s protagonist, unnamed for a reason, was in advertising. I use the past tense because the book starts at his funeral. His older, richer brother Howie helps to shovel dirt onto the protagonist’s coffin. His estranged sons are…sad. His loving daughter Nancy mourns. Maureen, his…nurse shows up. Before long, the funeral is over:

After fifteen pages of funeral, Roth remains in the past tense, and immediately takes the narrative back to the past:

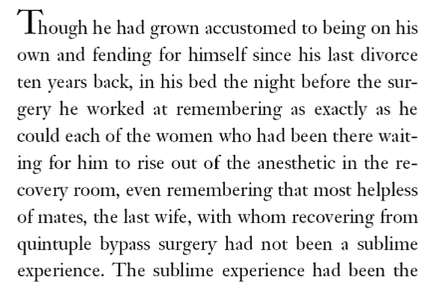

That’s right. Roth’s protagonist takes roughly chronological look back through his life. The hernia surgery he had as a kid. His first marriage, doomed by his first wife. His second marriage, doomed by his selfishness and uncontrollable urges.

To some extent, Everyman defies simple summary and I don’t want to give away too much of the plot. After all, isn’t that the joy of meeting someone new? That you get to gradually get to figure out who they are and have time to reach that full understanding? Everyman succeeds so well in part because Roth uses analepsis (flashback) to deliver the narrative and to give the reader time to absorb each development.

Have you ever gotten home to hear one of your significant other’s stories about his or her day? Perhaps it’s just my experience, but these stories (including my own) tend to be an exposition dump. The storyteller releases an awful lot of who, what, when and where. Of course, we love our significant others and are happy to listen, but the stories we contrive for our work should be easier to absorb. (Especially for those many strangers who read our work and have no context at all!)

Roth’s use of prolepsis allows him to release the narrative in bite-sized drips and drabs. You could say that the book is a set of connected short stories to some extent:

- The funeral

- The protagonist’s childhood hernia surgery

- The protagonist’s appendectomy in adulthood

- The protagonist’s bypass in later life

These “stories” are the bricks from which the story is made and they are held together by mortar that the powerful narrator uses to guide us along. This is the kind of narrator of that Roth needs to employ to keep us on board. After all, he has changed wives between the appendectomy and bypass and many decades have passed. These techniques allow Mr. Roth to focus all of his attention on the important parts of the main character’s life and to illuminate only the important relationships. A far more linear and “traditional” telling of this same story may have put more emphasis on the first wife. It may not be very easy to cram the whole of a man’s life into a stack of papers that is three-quarters of an inch tall, but Mr. Roth’s slippery use of time helps him accomplish this goal.

You have seen this advice before: avoid adverbs whenever possible. Writer’s Digest’s William Noble even turns the dictate into an order, saying, “Don’t Use Adverbs and Adjectives to Prettify Your Prose.” We have adverbs in our toolboxes, however. Just like any tool, we can use them…we must use them in a manner that improves our story in some way.

Mr. Roth uses adverbs in Everyman, of course, and I really admired the effect that some of his adverbs created. Now, adverb use can go wrong…very wrong. For example, here’s an exaggeration of a common mistake that some of us make:

She thought silently to herself mentally and was quite certainly having ideas in her head.

Why are these adverbs problematic? First of all, there are so many of them! Second, they don’t really add anything to our understanding of the sentence. (Can you think to anyone but yourself?)

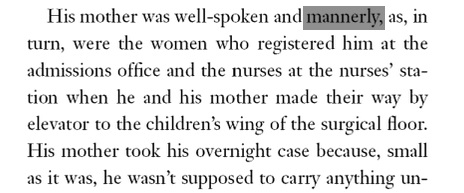

Mr. Roth makes wise use of adverbs. Sure, the primary intent of the adverb is to modify a “verb, adjective, other adverb, determiner, noun phrase, clause, or sentence.” I would argue that adverbs can have additional effects on the reader. Check out this example from Everyman:

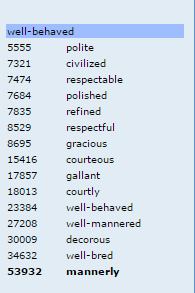

“Mannerly” is a slightly unexpected adverb. Take a look at a list of synonyms that I found during a search on wordandphrase.info:

We don’t tire of Mr. Roth’s use of adverbs in part because he chooses ones that we don’t see very often. Here’s another example:

Again, these are fairly uncommon words. More importantly, these adverbs are being used to regulate how the reader digests the sentence and its ideas. Isn’t that interesting? Mr. Roth had a lot of options with that very long sentence. Casting the sentence the way he did changes our perception. See?

Had he been aware of the mortal suffering of every man and woman he happened to have known during all his years of professional life, of each one’s painful story of regret and loss and stoicism, of fear and panic and isolation and dread, had he learned of every last thing they had parted with that had once been vitally theirs and of how, systematically, they were being destroyed, he would have had to stay on the phone through the day and into the night, making another hundred calls at least.

…had he learned of every last thing they had parted with that had once vitally been theirs and of how they were systematicallybeing destroyed… (Clause eliminated, allowing the reader to consume the sentence faster.)

…had he learned of every last thing they had parted with that had vitally once been theirs and of how they were being destroyed systematically… (Adverbs now sandwich more of the prose, bookending the thought more completely.)

Mr. Roth’s book succeeds for a number of reasons, not to mention the fact that it’s a very short and powerful read. What are some other books that turn the difficult trick of condensing a man or woman’s life into a comparatively small number of words?

Leave a Reply