What does it mean to be an “American writer?” A “Chilean poet?” A “Martian poet?” (I wrote a short story about that last one.) I don’t really know. I think that these delineations are as fuzzy as they are useful. Americans, Chileans, and (future) Martians have virtually everything in common; they’re human beings. We all feel hunger, love, and fear. We all seek to address these feelings in similar ways.

On the other hand, culture is influenced by climate and geography and food and a million other factors that add spice to the human experience. Why wouldn’t there be some kind of cultural flavor baked into the poetry a person creates? It’s a delicate balancing act, to be sure, judging a poet on the basis of such a label.

Anne Bradstreet is considered the first American poet. Though she died a century before Lexington and Concord, the sixty years of her life took place during the time when the ethos of the United States was still coalescing. Mrs. Bradstreet (she was a 17th-century Puritan…something tells me she would prefer “Mrs.” as an honorific) arrived in Massachusetts when she was 18 and spent her life in the colony. Her Puritanism definitely influenced her worldview and her work; as Charlotte Gordon asserts:

Anne Bradstreet’s work would challenge English politics, take on the steepest theological debates, and dissect the history of civilization. She would take each issue by the scruff of the neck and shake hard until the stuffing spilled out; no important topic of the day would be off-limits, from the beheading of the English king to the ascendancy of Puritanism, from the future of England to the question of women’s intellectual powers. Furthermore, she would shock Londoners into enraged attention by predicting that America would one day save the English-speaking world from destruction. Hers would be the first poet’s voice, male or female, to be heard from the wilderness of the New World.

Okay, enough of that stuff. What do we care about? Her writing and what we can learn from it! I was quite charmed by “The Author to Her Book,” a poem that I can reproduce here because it’s obviously in the public domain.

Thou ill-formed offspring of my feeble brain,

Who after birth didst by my side remain,

Till snatched from thence by friends, less wise than true,

Who thee abroad, exposed to public view,

Made thee in rags, halting to th’ press to trudge,

Where errors were not lessened (all may judge).

At thy return my blushing was not small,

My rambling brat (in print) should mother call,

I cast thee by as one unfit for light,

The visage was so irksome in my sight;

Yet being mine own, at length affection would

Thy blemishes amend, if so I could.

I washed thy face, but more defects I saw,

And rubbing off a spot still made a flaw.

I stretched thy joints to make thee even feet,

Yet still thou run’st more hobbling than is meet;

In better dress to trim thee was my mind,

But nought save homespun cloth i’ th’ house I find.

In this array ‘mongst vulgars may’st thou roam.

In critic’s hands beware thou dost not come,

And take thy way where yet thou art not known;

If for thy father asked, say thou hadst none;

And for thy mother, she alas is poor,

Which caused her thus to send thee out of door.

Notes for those who may not be comfortable with old-timey early modern English yet: I know. It looks weird. But the writing is almost 400 years old. Your writing will look weird 400 years from now, too. Some things to remember:

- Spelling was not yet standardized and words were assembled letter-by-letter by a compositor who built the movable type on the page. So when you see “joynts” or “hobling” instead of “joints” or “hobbling,” just go with it.

- Old-timey people would capitalize nouns, (as is the practice in German).

- The apostrophe in “caus’d” does the same work an apostrophe does now: it replaces a missing letter or letters. (In that case, the “e.”)

- Most of all, just go with it. This is not a complicated poem.

Okay, so what do we have going on here? Iambic pentameter. Rhymed couplets. Should we be surprised? Not really. Christopher Marlowe had popularized the use of iambic pentameter in poetry; Ben Jonson called it “Marlowe’s mighty line.” Bradstreet was born when Shakespeare was winding down and Jonson was still trucking along. (Marlowe was dead…or at least that’s what they want us to believe…) Mrs. Bradstreet did not reinvent the wheel. She made use of the conventions popular in poetry at the time. Now, this isn’t necessarily a bad thing. First of all, you can’t innovate until you understand how writing works. Second, you’re producing work that your audience can understand. Finally, working within a structure allows you to stretch out and do something different in a different area of your work.

Mrs. Bradstreet indeed tackles an “unusual” subject in her poem: authorship. (And authorship by a woman, which was uncommon at the time!) It’s hard to believe now, but people didn’t see “authors” in the same way they do now. Copyright was a joke. There was no “Author! Author!” The aforementioned Ben Jonson was one of the first to write about the concept of the author. And look what Mrs. Bradstreet wrote decades later! A poem that oozes with a writer’s love for and regrets about her work! (It is also clear that Mrs. Bradstreet felt the same way about her work as we often do upon publication: we love the piece, but we still see its flaws.)

Importantly, this is not just a poem about poets. Mrs. Bradstreet keeps the poem relatable by making a comparison that we can all understand. Don’t we all think of our poems, short stories, essays and novels as our babies? Whether or not they have children of their own, non-writers can also relate to the comparison. See how this idea is useful, especially in a short poem like this? Mrs. Bradstreet did not overcomplicate things. I’d wager that if you could ask her about her poem, she would not say it was “about the incalculable search for understandingness in a worldrealm unfeeling to the now” or some such opaque twaddle. Remember; reading is not supposed to be homework. We do the reader a disservice when we encode meaning so deeply that the work is confusing and requires the reader to get out a pen and paper to chart what is happening in the poem.

Look at the world in which Mrs. Bradstreet was creating. This is a map of what the east coast of North America looked like around the time the poem was written:

Isn’t it amazing? Mrs. Bradstreet was in a world greatly in flux. Everything was changing and little was set. Childbirth was a real nail-biting experience and the elements were a real danger instead of an inconvenience. I suppose the biggest lesson we should learn from the author is that we should put aside the concerns of the day when we write. Authorship is our stab at immortality. It may not help the plants in your garden to grow or lure small game into your traps, but it is a reflection of personal identity in addition to national identity. Even though we all have a million problems on our minds and we’re trying to build our own figurative country (just as Mrs. Bradstreet was trying to build a literal one), the writing we do about ourselves and what we think and how we feel can matter a great deal.

Especially if we have something meaningful to say.

Poem

Anne Bradstreet, Independence Day

During World War II, the brave Allied servicemen in the Pacific theater were missing the comforts of home. Instead of Mom’s cooking, they were trying to swallow cold MREs in an unfamiliar climate halfway across the world. The men were scared: for their lives, for their country, for the relationships they put on pause to do their duty.

The political and military brass of Empire of Japan did the perfectly natural thing: they tried to take advantage of these feelings in order to demoralize the enemy force. Enter Tokyo Rose, the collective name for the sweet-voiced women who narrated radio broadcasts intended for American soldiers and sailors in the Pacific. The Pentagon and private agencies did their best to help the men keep their minds occupied while in theater-distributing radio programs, movies, paperbacks, comic books-but there was always an audience for any English-speaking voice they could catch over the airwaves.

Tokyo Rose told the Americans how beautiful Japan was and softly, sweetly urged them to give up hope that they would defeat the mighty forces of the Empire. She cooed into the microphone and told the guys about their girls back home, how Sally Strongheart from All-America, Kansas, wasn’t waiting like she promised. No, she was going to the sock hop with that 4-F she always said was just a friend.

See for yourself:

Of course, the propaganda effort didn’t work because Americans are so awesome (USA! USA! USA!), but the story reveals an important lesson about craft. The rhetoric of Tokyo Rose was not bombastic. She didn’t scream. No, she calmly appealed to the fears of her listeners. See how this relaxed and logical approach was a much better idea than, say, endless screeching?

We write because we have stories we need to tell, ideas we need to share. Our hearts burn with the need to commit our thoughts to paper and share them with others. But here’s the problem: we can’t get our message across if all we do is burn. No, the heat must be focused and have a purpose. In the words of the late, great Christopher Hitchens: “heat is not the antithesis of light but rather the source of it.”

Here’s an example of heat that produces no light, that casts no illumination whatsoever on the world or the human condition. This young woman was not pleased to see a Donald Trump banner on her campus. I think you’ll agree with me that she doesn’t make a very compelling argument.

I think you’ll agree with me that this young woman did not win any hearts and minds to whatever the heck she was thinking.

We are in a new and fascinating age of political literature. (I wish this age had begun fifteen years ago, but so it goes…) As reading rates have declined, the writing community has become ever more liberal, or whatever term you would like to use. On some level this makes sense. Writers have always been curious about others. We’ve always used empathy to put ourselves into the lives of others. But I think it’s reasonable to admit that the balance has shifted even further to the left than usual.

There are such amazing opportunities for writers! There are so very, very many things to say in this absolutely crazy political climate. We all want writing to remain what it has always been: a vehicle for entertainment social chronicle and change. Unfortunately, our work becomes less useful and less effective if we figuratively prance around the yogurt-puddled quad screeching at people who both agree and disagree with us.

Protest literature is boring and pointless when it’s all heat and no light, when it’s a screech instead of an argument. That is why I was so pleased to read a protest poem that actually meant something. Rachel Custer’s “How I Am Like Donald Trump” appeared in Rattle’s Poets Respond feature. Published a couple weeks before the election, the poem is not at all pro-Trump, but it’s also not packed with breathless hyperbole and unchanneled anger.

First of all, look at the title. Ms. Custer literally identifies with Trump and makes it clear that she is employing empathy. A writer can hate a character all they like, but they must empathize with the person about whom they are writing. No, this doesn’t mean that you forgive or even like a person. You must understand, to paraphrase the great Lee K. Abbott, who the character is in the dark.

Then Ms. Custer dedicates the poem, “for D.T. and other lonely people.” I know. I agree. Trump is bad. I don’t like his policies. I don’t like some of the things he has said. Did we gain anything from yet another affirmation against Trump? No. But we do get something out of thinking of the “villain” as a real human being, in this case a “lonely” one. For some reason, many of us are forgetting that the old-fashioned mustache-twirling bad guy who is just bad has fallen out of style. No, we like our villains to be complicated and to resemble real people who have real motivations. Thinking of Trump (in this case) as a real human being also makes your protest art more effective. Instead of arguing against a strawman, you’re arguing against a flesh-and-blood man.

The poem itself, it seemed to me, was quite sad and evocative. Ms. Custer could have been like so many other writers and written:

OMG I HATE TRUMP

HE SAID MEAN THINGS ABOUT THAT BEAUTY PAGEANT CONTESTANT

AND RUINED BILLY BUSH’S

CAREER.

See? Only heat. No light. Ms. Custer’s Trump is revealed to be a sad and pitiful man; her work is more effective than a thousand screeching undergrads. You can’t unseat a politician unless you understand them and why they do what they do. You can’t make a deal with a person unless you understand their psychology.

Ms. Custer uses the heat in her heart to generate light instead of merely adding to the fury that we find in so many places. Let’s try to do the same thing when next we try to change the world with our words.

Poem

Rachel Carson, Rattle

We all love Joyce Carol Oates for her beautiful and engaging work, for her steadfast advocacy of other writers, for her dedication to helping all of those who dare to turn thoughts into literature. Ms. Oates is also active on Twitter, yet another way in which she remains of prime relevance in our community.

Ms. Oates recently hit upon something that I think about a lot, even though it doesn’t apply to me in the least. As Shakespeare said through Cassio, our reputations are the immortal parts of ourselves and “what remains is bestial.” One reason that most of us bother to write at all is that we wish to ensure that some part of us may remain for many future generations. We hope that our stories and ideas may resonate hundreds of years from now, as Shakespeare’s do. Ms. Oates’s novels and stories will survive as long as humans crave stories (which is forever), but most of us will see our influence wane until it flickers and snuffs itself for lack of attention. (Out, out, brief candle!)

Ms. Oates reminded us of our temporary nature in a witty and Oatesian way, saying:

Ms. Oates name-checked some writers who have lost relevance in the canon over the past few decades:

Whatever the reasons, my heart went out to these writers, each of whom had the same dreams and goals and joys that are shared by every writer. They were also lucky enough to shape the community, for good and ill, through the generations of students who looked to them for wisdom and advice in the craft.

Other writers may be in the process of overwriting what they did during the twentieth century-such is the march of time-but let’s give a little attention to these writers, people who still have something to teach us.

To my shame, I had not previously read Howard Nemerov, but I am glad that Ms. Oates’s tweet did its job. Mr. Nemerov’s work, a nice sample of which can be found at the Poetry Foundation web site, is graceful and accessible in a way that demands a wider audience. A great deal of contemporary poetry, I am sad to say, seems contrived to confuse. Any time I have tried to introduce such work to young adults, they go away scratching their heads and checking their phones. When you show them a work such as Randall Jarrell’s “The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner,” they go away thinking about the horrific nature of the ball turret gunner’s death and checking their phones.

Mr. Nemerov enjoyed working in forms and playing with meter and rhyme. (Another strike against him, it seems…) Judging from the sample I have enjoyed, Mr. Nemerov’s poems are relatable in the same way as those of Billy Collins: they often deal with parenting, aging and nature. These are subjects to which your non-writer (and perhaps non-reader) friends can relate, and Mr. Nemerov writes about them in a manner that these same friends can understand.

I suppose this is the first lesson we can take from Mr. Nemerov’s work. People love playing with language. They love contemplating where their life has gone and where it has been. Instead of cloaking our own profound thoughts in deliberately obtuse language, perhaps we should be more open to using meter and rhyme in a way that is accessible to those who have not yet earned their own MFA.

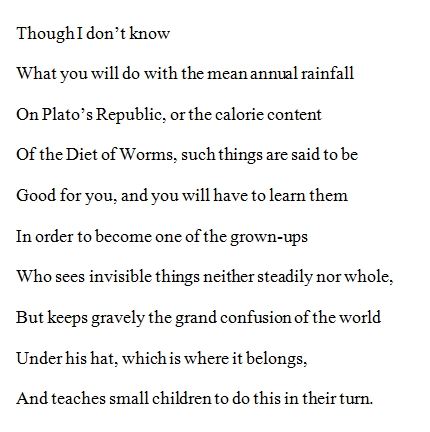

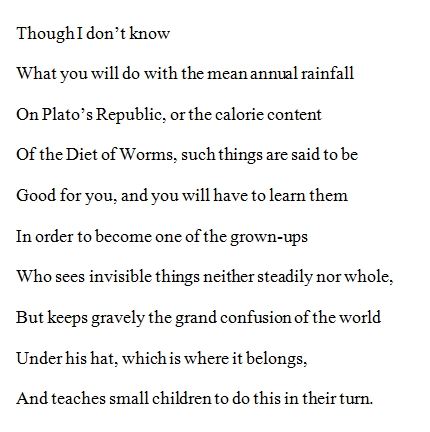

Let’s take a closer look at an extract from a poem called “To David, About His Education.”

What do we notice? Mr. Nemerov employs, in my view, a somewhat loose iambic pentameter in the poem. Unlike a more rigid example (“shall I comPARE thee TO a SUMmer’s DAY?”), the stressed and unstressed syllables are harder to identify. I wonder about the effect of this looser meter; are these lines more “accessible” to those who don’t yet realize they like poetry?

What do we notice? Mr. Nemerov employs, in my view, a somewhat loose iambic pentameter in the poem. Unlike a more rigid example (“shall I comPARE thee TO a SUMmer’s DAY?”), the stressed and unstressed syllables are harder to identify. I wonder about the effect of this looser meter; are these lines more “accessible” to those who don’t yet realize they like poetry?

You’ll also notice, for good and ill, that Mr. Nemerov’s use of meter forces him into making word choices. Look at that last line. Is “their” really necessary for us to understand what the poet means? I don’t believe so. Without that additional word, however, the meter breaks down. Where Mr. Nemerov is playful with the meter in much of the rest of the poem, he wisely ends it with a fairly solid line of blank verse:

and TEACHes small CHILdren to DO this IN their TURN.

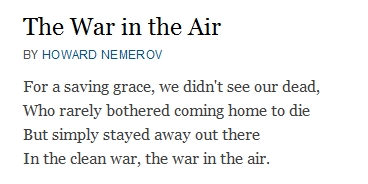

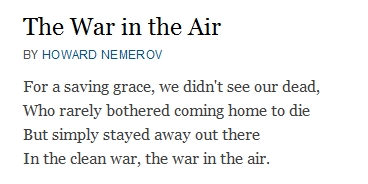

One of Mr. Nemerov’s more famous poems is “The War in the Air.” Here’s the first stanza:

It bears mentioning that Mr. Nemerov served in the Royal Canadian Air Force and the U. S. Army Air Forces during World War II. Perhaps the first thing we notice is now Mr. Nemerov is playing with meter and rhyme. The first two lines of each stanza are cast in that “loose” iambic pentameter and the last two lines of each stanza rhyme.

It bears mentioning that Mr. Nemerov served in the Royal Canadian Air Force and the U. S. Army Air Forces during World War II. Perhaps the first thing we notice is now Mr. Nemerov is playing with meter and rhyme. The first two lines of each stanza are cast in that “loose” iambic pentameter and the last two lines of each stanza rhyme.

Rhyme and meter are somewhat out of fashion today, but they will always be included in the poet’s toolbox. Why do I love that this poem follows some rules? The rhyme and meter contribute to the feeling of the poem. We can all agree that Mr. Nemerov saw some terrible sights during his time as a pilot and anyone who has spoken with a veteran knows that they took and still take what they did very seriously. The structure imposed by rhyme and meter, it seems to me, facilitate the kind of solemn reflection appropriate to the subject of the work.

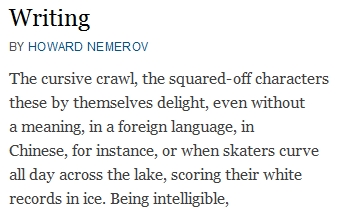

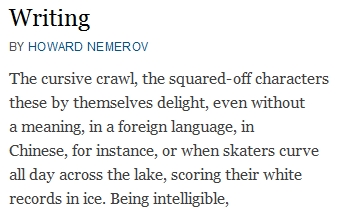

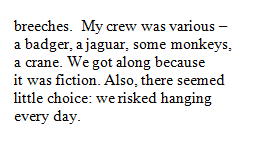

Like most writers, Mr. Nemerov reflected upon his avocation. Check out the beginning of his poem, “Writing”:

The first thing we notice is that the poet is adhering more strongly to the meter than was the case in the first two poems. Isn’t that image a beautiful one? Mr. Nemerov reminds us that everything about language is beautiful, including the very pen strokes we use to communicate our thoughts.

The first thing we notice is that the poet is adhering more strongly to the meter than was the case in the first two poems. Isn’t that image a beautiful one? Mr. Nemerov reminds us that everything about language is beautiful, including the very pen strokes we use to communicate our thoughts.

If nothing else, Mr. Nemerov deserves to be remembered for the decades of devotion that he gave to the writing community. Not only was he the Poet Laureate, empowered to spread the gospel of poetry far and wide, but he nurtured generations of poets as a teacher. So thank you, Ms. Oates, for reminding us of a writer whose name deserves to be on our tongues, if not for all time, at least a little longer.

Poem

Howard Nemerov, Joyce Carol Oates

The year was 1995. Hope was high and life was worth living. “Google” meant a large number. Some phones still had cords and it was really hard to sext if you were using a rotary dial.

1995 was the heyday of American culture and you couldn’t log into AOL via dialup without reading about The X-Files. Mulder and Scully were the hottest protagonists on TV and David Duchovny and Gillian Anderson together were singlehandedly spurring interest in the newfangled Internet. Not only were both of them physically attractive, but both projected a distinct intelligence and depth. So strong was their chemistry and the stories they told that The X-Files is returning for a six-episode miniseries event in January 2016.

Yes, in 1995, it seemed that David Duchovny could do anything. (Now he can only do 99.5% of the things.) He could even introduce teenage me to William Carlos Williams.

In those days, I consumed as much information as I could about the show and dreamed of one day writing for such a program. I remember the September 1995 issue of Entertainment Weekly because Benjamin Svetkey’s article pointed out that David Duchovny, this big TV star, wrote poetry.

“Hey!” I thought. “I write poetry! I could be like him, just without the money or women!”

I wasn’t particularly moved by the episode in which Mr. Duchovny wore a red Speedo, but I knew many others were. I did, however, appreciate Mr. Duchovny’s off-the-cuff twist on some guy named William Carlos Williams:

My Speedo

So much depends upon a red Speedo

Covered with rain

The next time I was in the school library, I looked up this William Carlos Williams fellow and found my horizons expanded. I thought about the connection between Mr. Williams’s wheelbarrow and Mr. Duchovny’s Speedo and, well, I tried not to read too much into it.

The point is that my enjoyment of the interview and my respect for Mr. Duchovny increased once I understood the allusion he was making. (It’s important for a writer to have a wide frame of reference.) Now that I’m slightly more mature than I was in 1995, I can also appreciate that Mr. Duchovny was blending high and low culture. (I sometimes feel the balance is…off.) Mr. Duchovny and Mr. Williams also offer poetry that is abstract, but is relatively easy to understand and enjoy if you give it a chance. (As I keep saying, we need to #MakeMoreReaders.)

Why not follow Mr. Duchovny’s lead and rewrite a classic poem of your own? While you are at it, check out Mr. Duchovny’s novel as you wait for the X-Files premiere on January 24. We can’t go back to 1995, when the sun shone and the lilacs were in bloom. We can, however, be like Mulder and Scully-and Duchovny and Anderson-by showing the world that age may take its toll, but we can still produce better work than ever before. Even though we may want an occasional nap or a pair of comfortable shoes.

If you found my analysis useful or enjoyed my writing style, would you consider checking out Great Writers Steal Press, where I have published some eBooks of the fiction and nonfiction variety? Just head over to books.greatwriterssteal.com, where reading is not homework!

Poem

David Duchovny, The X-Files, William Carlos Williams

Writers are asked many general questions about their craft.

…”What is your overarching philosophy regarding the inherent power of fiction?”…”What IS-character-to you?”…”What is the position of place in your work?”…

These are great and important questions, but I’m really curious about the little things. In the “Hey, Why’d You Do That” series, I ask accomplished writers about some of the very small choices they made during the process of composition.

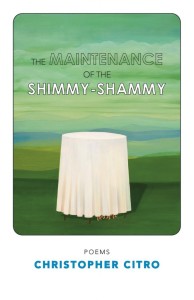

Christopher Citro is one of those writers whose names seem so familiar because you keep seeing it in all of your favorite lit mags. His work has appeared in a ton of places, including The Journal, Ploughshares, Redivider and a number of other journals you wish would accept your own work. His first book of poetry, The Maintenance of the Shimmy-Shammy, was published by Steel Toe Books. Why not order a copy directly from the publisher? You can also find the book at Barnes & Noble and Amazon.

Yes, you may wish to read 10,000 words in which Mr. Citro elucidates his overall philosophy of poetry. Instead, I am curious about the tiny choices that Mr. Citro wrestles with every time he sits down to put pen to paper. I read and enjoyed “Nerve Endings Like Strawberry Runners,” a poem that Mr. Citro placed in Witness. Why not follow along with the poem and reflect upon the nitty-gritty of his writing process in order to improve your own work? Continue Reading

Poem

Christopher Citro, Why'd You Do That?, Witness

Writers are asked many general questions about their craft.

…”What is your overarching philosophy regarding the inherent power of fiction?”…”What IS-character-to you?”…”What is the position of place in your work?”…

These are great and important questions, but I’m really curious about the little things. In the “Hey, Why’d You Do That” series, I ask accomplished writers about some of the very small choices they made during the process of composition.

Deborah Guzzi is a Connecticuter whose poetry has been published in markets all over the world. Some of that work appears in 2015’s The Hurricane, a collection published by Prolific Press. Please consider purchasing the book directly from them, but you can also get the book from Amazon or Barnes & Noble.

You can (and should!) learn more about Ms. Guzzi through her Twitter feed and her YouTube page.

Ms. Guzzi was kind enough to suggest we discuss her poem, “The Sowing.” The poem is available here for free. I was touched by how much she clearly loves her poem and feels that the piece is doing good with respect to domestic violence and rape: issues that are near and dear to the hearts of many of us. As my Ohio State MFA colleague Laurel Gilbert is also greatly interested in these problems, I thought it would be interesting to see what she would ask Ms. Guzzi about her poem. (I was right.) Continue Reading

Poem

Deborah Guzzi, Prolific Press, Why'd You Do That?

Show Notes:

Enjoy this interview with Rosalynde Vas Dias, author of Only Blue Body, winner of the 2011 Robert Dana-Anhinga Prize for Poetry.

Take a look at the Facebook page Ms. Vas Dias created for her book. She shares a lot of very helpful links!

https://www.facebook.com/OnlyBlueBody?fref=ts

Order your copy of Only Blue Body from Anhinga Press:

http://www.anhinga.org/books/book_info.cfm?title=Only%20Blue%20Body

Here is Katie Riegel’s brief but kind review of the book:

http://applewordkiss.blogspot.com/2013/04/only-blue-body-by-rosalynde-vas-dias.html

During our discussion, I asked Ms. Vas Dias why she constructed a bit of her poem “Hidden” the way she did. Here’s the relevant bit of poem:

I mention http://www.penbuzz.com/, a new social media site for writers. Why not give it a look and feel free to friend me? I’m “GreatWritersSteal.” Of course.

Visit my website: http://www.greatwriterssteal.com

Like me on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/GreatWritersSteal

Follow me on Twitter: @GreatWritersSte

Music: “BugaBlue,” Live At Blues Alley by U.S. Army Blues is licensed under a Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

http://freemusicarchive.org/music/US_Army_Blues/Live_At_Blues_Alley/

Many thanks to the Library of Congress for their beautiful public domain images:

http://cdn.loc.gov/service/pnp/fsa/8b24000/8b24900/8b24943v.jpg Holstein cow at Casa Grande Valley Farms. Pinal County, Arizona. She yielded 497 pounds of butterfat in 370 days. On test 77 cows of the Casa Grande Farm yielded an average of 386 pounds of butter fat in 365 days. This was the highest in the state for that many cows

http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/hec2013004924/ Wife of New York department store magnate captures first and second prizes at Washington Horse Show. Mrs. Bernard Gimbel, wife of the New York department store magnate, and her horses Capt. Doane (left) and welcome with with whom she captured first and second prizes in the Ladies Hunters class at the National Capital Horse Show today. Capt. Doane is the $12,000 dollar horse who has been capturing many blue ribbons in eastern horse shows recently

Poem

Anhinga Press, Katie Riegel, Rosalynde Vas Dias

Title of Work and its Form: “”In the style of Joan Mitchell”,” poem

Author: Janelle DolRayne

Date of Work: 2014

Where the Work Can Be Found: The poem debuted in the October 2014 issue of inter | rupture. You can find it here.

Bonuses: Here is an apt poem that was subsequently chosen for Best of the Net 2013. Here is a reading list that Ms. DolRayne put together in her capacity as Assistant Art Director for Ohio State’s The Journal. Want to see the poet read her work?

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Conceits

Discussion:

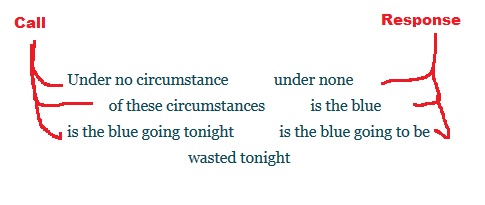

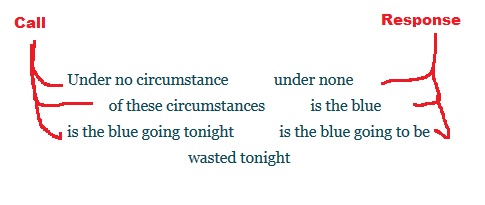

Ms. DolRayne offers us a poem with a fun and interesting conceit. (It bears mentioning that Ms. DolRayne may not have the same idea as I do about her poem…but that’s okay.) It seemed to me that the poem is a powerful attempt to use poetry to mimic the loose and quietly powerful feel of a folk song. If you’ll notice, the first few stanzas feature lines that employ the call-and-response technique popular in folk, blues and rock music:

You’ll also notice that the last stanza abandons the conceit, which is perfectly fitting. The narrator of the poem is now speaking in “unison” or “a cappella.”

You’ll also notice that the last stanza abandons the conceit, which is perfectly fitting. The narrator of the poem is now speaking in “unison” or “a cappella.”

First, I’ll give you some examples of the call and response I’m talking about. Phil Medley and Bert Berns wrote “Twist and Shout,” a song that was covered by a lot of groups, including The Beatles. You’ll notice that the background vocalists mirror and augment the lead singer.

Steven Page and Ed Robertson wrote “If I Had a Million Dollars.” As I understand it, Ed had written the bulk of the song, but only had his part of the vocal. Mr. Page heard the song in progress and added his part. Mr. Page sometimes simply repeats Mr. Robertson’s part; sometimes he adds to the narrative of the song and takes it in a new direction.

The response doesn’t even have to come from a vocalist. In George Thoroughgood’s “Bad to the Bone,” the response comes from guitar and saxophone.

I loved Ms. DolRayne’s use of this technique for a number of reasons:

- Poetry is just a kind of music, right? Why not make that connection explicit in this way? Some people think poetry is a fancy-pants thing you read because some teacher told you to. Those same people love music without realizing poetry does many of the same things.

- The “call and answer” adds another voice to the poem, even though it’s only being written by one author. In this way, we’re able to produce a kind of harmony.

- The images and ideas in the poem are reinforced through repetition and through being conceptualized in a different way.

- The phrases on each side of the large spaces can be considered poems unto themselves and these poems are in conversation with each other, aren’t they?

One of the inherent difficulties in writing is bridging the gap between thought and the written word…and trying to figure out how to combine words, space and punctuation in such a way that the reader will understand the thought you had. Ms. DolRayne literally adds in the pauses that led me to treat her poem like a kind of song. For the poet, those pauses are spaces between words. For a singer, those pauses are bits of silence between musical phrases. Why not take Ms. DolRayne’s idea and try to lay down some prose in the style of a musician?

I think one of the reasons that I identified the call-and-answer conceit in the poem is because the poem was challenging me, inviting me to make sense of it in a way that made me happy. If you’re near a window, look out at the clouds. What shapes you do see? A phenomenon called “pareidolia” forces us to make sense out of “vague or random” stimuli.

Now, that’s not to say that Ms. DolRayne has given us a poem filled with randomness, because she didn’t. That’s writing craft in a nutshell, folks. The poet had to work very hard to create a work that clearly communicated her own thoughts while ensuring the piece was open enough to allow the reader to draw his or her own conclusions.

Unfortunately, there’s no easy method by which writers can learn to be simultaneously specific and vague. That’s just not something you can learn with a step-by-step procedure. Instead, we just need to read a lot of poems and write a lot of poems and hope that our skills improve to the point where we have the power to turn any trick we like.

What Should We Steal?

- Think of yourself as a songwriter when you compose. The conventions of music are not exactly the same as the ones writers use, but we can use their prose equivalents to our advantage.

- Trigger your reader’s pareidolia. How can you get your reader to see the plan in what seems like randomness?

Poem

2014, Conceits, inter|rupture, Janelle DolRayne, Ohio State

Title of Work and its Form: “I Heart Your Dog’s Head,” poem

Author: Erin Belieu (on Twitter @erinbelieu)

Date of Work: 2006

Where the Work Can Be Found: The poem appears in Black Box, Ms. Belieu’s 2006 Copper Canyon Press book. The Poetry Foundation has made the poem available on its web site.

Bonuses: Check out this great interview the poet gave to Willow Springs. Ms. Belieu also conducts interviews with poets. Want to hear Ms. Belieu read her work? (Sure, you do.)

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Subject Matter

Discussion:

Poems have to be all dark and depressing, right? Don’t poems have to illuminate the author’s saddest thoughts? Appropriate subject matter for poems: romantic break-ups, deceased pets and the worst day you ever had…right?

Of course not! Poems can also be fun and can deal with any subject under the sun-or beyond. Ms. Belieu’s free verse poem is about her reaction to watching Bill Parcells coach a game on television. Now, the poet makes it clear she doesn’t care about football, but she understands that football, like everything else, is a chapter in the vast narrative of our society. After discussing her antipathy for Mr. Parcells, Ms. Belieu reveals her history of not caring about football despite having been born in Nebraska, one of the places where football is a particularly prominent part of the social fabric. The thought leads her to recall the barking Chihuahuas on her street. Finally, Ms. Belieu “puts her faith” in reincarnation, hoping that Mr. Parcells is someday “trapped in the body of a teacup poodle” so she can hear his yapping.

I loved that Ms. Belieu wrote a poem about a popular subject. Too many folks think that poems must be inaccessible and must deal with “fancy-pants” topics…not so! Football is the same as any other human endeavor; poets have the right to take a look at the sport with the full power of their critical acumen. I have done the same on occasi0n, writing poems for my blog on my favorite Ohio State sports site. (Why do I write poems for a community that is sport-centric? Well, poetry belongs everywhere and we shouldn’t assume that a “sports fan” doesn’t like what we do.)

The overall point is that we have permission to take on any subject we like. Football, computers, cars, Kardashians, the latest episode of Hell’s Kitchen…they’re all within our purview as artists. More importantly, we SHOULD interact with the rest of what is happening in our culture. Writers are the people who make sense of the world; we chronicle the evolution of the human soul.

Even better, Ms. Belieu doesn’t make the poem solely about football. Everything that we do means something more than is apparent on the surface, right? Just before the final stanza, she builds upon her football- and Chihuahua-related discussion. Why were those lines important? Well, they led her to think about “what’s wrong with this version of America.” She engages in cultural criticism, seeming to raise issues regarding the tribalism inherent in sport (Go Bucks!) and perhaps the obligation people feel to like a team just because their parents did. People like Bill Parcells, who she feels is happy and successful for the wrong reasons, will win the game, in spite of his sins. (Are you curious as to whether Mr. Parcells won in the game to which Ms. Belieu refers? Me too. Well, Mr. Parcells left the Jets in 1999 and returned to coaching with the Cowboys in 2003. At the time, the Giants and Jets shared Giants Stadium, part of the Meadowlands Sports Complex. The Cowboys played the Giants in Week 2 of the 2003 season. The score? Well, Mr. Parcells and the Cowboys won the game in an overtime thriller, 35-32.)

A writer can’t simply tell a story or provide his or her reader with a bare description of something; it’s our job to explain what that thing means. That single game is now pretty irrelevant, relegated to the memories of those who attended and to box score statistics. Thanks to Ms. Belieu’s insight, however, that 2003 game can still have a big effect on us. After all, we read the poem and it had some impact upon us!

I’ve been wracking my brain as to why Ms. Belieu made a specific choice in the poem. Approximately halfway through, she writes:

…of breaking a soul. Yes,

there’s the glorification of violence, the weird nexus

knitting the homo, both phobic and erotic,

but also, and worse, my parents in 1971, drunk as

Australian parrots in a bottlebush, screeching…

Look at that middle line. I love the way she condenses two words that are somewhat long and unwieldy. Instead of burdening the line with both “homophobic” and “homoerotic,” she is using language in a somewhat playful way and is inviting us to do the same. As I said, I do wonder why she cast the line that way. Why not:

knitting the homophobic and homoerotic

Well, as I said, I like the fun use of language. But why did she use commas when she could have used em-dashes?

knitting the homo—both phobic and erotic—

Or parentheses? After all, that second clause is a parenthetical statement.

knitting the homo (both phobic and erotic)

I’m certainly not criticizing Ms. Belieu’s choice; I’m just trying to understand the effect the choice has so I can use it in my work in the future. I think that the commas keep the poem flowing more fluidly than parentheses would. (A parenthetical thought might stop the reader for a moment. Didn’t this parenthetical thought stop you just a little?)

The lines that contain that fun sentence benefit from the slipperiness of the comma instead of the businesslike interjection of parentheses.

What Should We Steal?

- Empower yourself to confront any element of the human experience. There can and should be poems (and stories) about everything that has an effect on human beings.

- Add relevance to something that may seem irrelevant. I’m a big baseball fan and I love my Detroit Tigers. The Tigers play 162 games a year (not including the playoffs). It’s hard for me to remember a game a week after it’s played; the ones that endure in my memory are the ones to which I applied a special significance.

- Contrive your lines with the sounds of the words and phrases in mind. Even if you’re breaking a grammar rule or two, your higher duty is to communicate your thought to the reader in the most efficient way.

Poem

2006, Copper Canyon Press, Erin Belieu, Ohio State, Subject Matter

Title of Work and its Form: “Falling,” poem

Author: James L. Dickey

Where the Work Can Be Found: “Falling” has been anthologized about ten trillion times. You can also find the poem on the Poetry Foundation web site.

Bonuses: Here is Mr. Dickey’s New York Times obituary. Here is an interview Mr. Dickey gave to The Paris Review. What did the poet hope would happen when people read his work? Check out his answer:

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Punctuation

Discussion:

This “long” and fun poem tells a real-life story: that of a stewardess who fell out of a commercial airplane, meeting an unfortunate end at the hands of physics and fate. The poem begins as the woman is rummaging for blankets and completing her commonplace duties. Without warning, she is sucked out of the plane and falls to the earth. The plot of the poem may be simple, but it packs a big wallop because of the way Mr. Dickey uses language to describe her actions and thoughts as she endures what she learns will be the last couple moments of her life. The free verse work is split into seven stanzas that increase in intensity, culminating in a chilling final line:

There’s SO MUCH to learn from this poem that I should just jump right in, but I can’t help but point out one reason I’m writing about “Falling.” We all love Stephen King, right? Well, he gave an interview to The Atlantic‘s Jessica Lahey in which he discusses his views on craft and teaching. During a discussion regarding which kind of work has the biggest impact on young readers, Mr. King says:

When it comes to literature, the best luck I ever had with high school students was teaching James Dickey’s long poem “Falling.” It’s about a stewardess who’s sucked out of a plane. They see at once that it’s an extended metaphor for life itself, from the cradle to the grave, and they like the rich language.

Mr. King, of course, is correct in his assertions and “Falling” is the kind of poem we should all have under our belts.

What do we notice first of all? Well, Mr. Dickey stole the idea of the poem from a real news article. This one, in fact. Unfortunately, Mr. Dickey is no longer with us, so we can’t ask him about his exact motivation. It’s safe to say, however, that Mr. Dickey was probably struck by the terror and freedom the young woman experienced during her descent. Why shouldn’t you do the same thing? The next time you read a news story that strikes you, why not jot down a few lines. After all, most of us are moved by news stories and anecdotes we hear and the like. We’re never at a loss for inspiration if we make use of the infinite number of stories that surround us. There are also infinite angles you can take when borrowing from the news. You can simply retell the story. Or you can set the events 500 years in the future. Or you can devote the narrative to an observer. Or you can do as Mr. Dickey did, delving deep into what he imagined the stewardess was thinking and doing as the surly bonds of Earth reclaimed her.

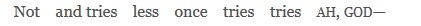

And now, it’s time to do a little counting. I know…I know…so many of us become writers because we don’t want to deal with a ton of numbers. Unfortunately, statistical analysis can help us understand what makes “Falling” so effective. You’ll notice that Mr. Dicket doesn’t cast his lines in a traditional manner. That’s just fine, of course; the fragmented run-on lines mimic the stewardess’s mental state. I’m betting that it’s pretty hard to form coherent sentences when you’re at terminal velocity without a parachute.

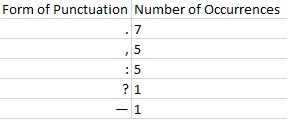

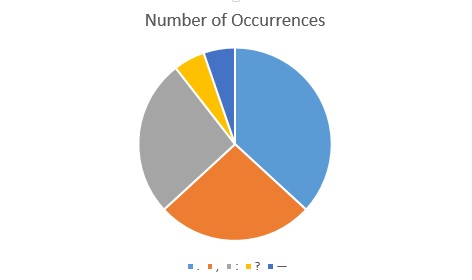

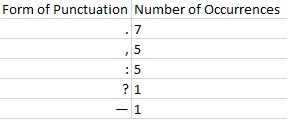

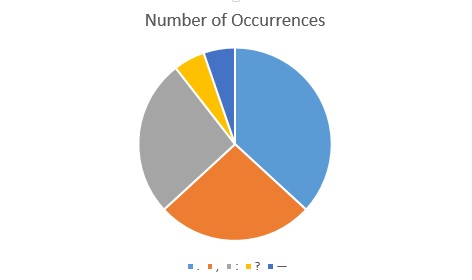

Mr. Dickey still had an obligation to help us figure out how we should split up the lines. And he also has the responsibility to let the reader take a breath. (We don’t want people to pass out at poetry readings, do we?) So how does he manipulate the prose to allow respiration and to communicate the feeling of disjointed thought? Well, you see all of those spaces in the fairly long lines. But you’ll notice that he also uses punctuation, albeit sparingly. Here’s a table that breaks down his use of punctuation in the poem:

Want to see the data in chart form?

Want to see the data in chart form?

Only 19 punctuation marks? In such a long poem? Crazy!

Well, not really. Mr. Dickey used the punctuation like spice, placing the marks only where they were utterly necessary. You’ll also notice that the end of the poem-the time when the character is most despondent, we might assume-only includes two marks, including the one at the very end. By that time, Mr. Dickey has taught us how to read the poem; he doesn’t need to provide the kind of guideposts that were much more of a necessity earlier in the poem. What’s the overall point? We must string together words in the manner appropriate to the work and mortar them together with the proper punctuation…even if that means omitting the marks altogether.

Another great thing about the poem is that Mr. Dickey actually gives the fictionalized protagonist things to do. Now, the unfortunate real-life stewardess may not have imagined she could save herself by diving into water. She may not have removed her jacket and shoes on purpose (or at all). It’s sad, but we have no way of knowing what she was thinking because she wasn’t around to tell us the next day. One of the big problems that a lot of people have when they fictionalize a real event is a lack of imagination. (At least, this failure is certainly a problem for me!)

When we are molding creative works, we shouldn’t forget that we can change anything we like about the characters and the plot. What a freeing notion, right? Like me, you may think of the perfect thing to say to someone…an hour after you should have said it. These restrictions are loosened in creative writing. By all means, if you are writing about your childhood, your best friend doesn’t have to live next door. Your first boyfriend or girlfriend doesn’t have to break your heart and show up to school looking blissful the next day. It’s not entirely necessary that your parents got divorced. Why? The characters aren’t really your best friend, significant other or parents. It’s your world, friend. You get to decide what joys and pains your characters endure.

What Should We Steal?

- Write your own version of a true story. What was going through the minds of American sailors during the attack on Pearl Harbor? What were the Japanese kamikaze pilots thinking?

- Shape your lines and use punctuations according to your needs. If you are trying to craft breathless lines for a breathless character, you might not want to use a lot of periods. (Periods are also called “full stops.” Stopping certainly wouldn’t be a good idea for this kind of character.)

- Feel empowered to fictionalize real-life situations. You are your characters’ puppet master. Pull the strings. But don’t take my word for it. Take the advice from Bela Lugosi:

Poem

Classic, James Dickey, Punctuation, Stephen King