One of the great problems with contemporary literature is that it often overlooks the problems of the “average” person. The middle-class people (whatever that means in 2017) who worry about keeping a roof over their heads, who beat themselves up because they can’t buy their kid hockey gear for tryouts.

Netflix wisely picked up two seasons of F is For Family, an animated show created by all-time great comedian Bill Burr and all-star The Simpsons writer Michael Price. (That’s right, two people who have achieved everything I wanted to be well into adulthood. You can tell I’m at least a little bit of an adult because I have enough maturity not to hate them for it.) The program tells the story of the Murphy family, a middle-class suburban family in the 1970s. Frank and Sue have three children and a thousand concerns. I’ll go light on the Season 2 spoilers, but Frank has lost his job with Mohican Airways and is feeling pretty worthless. His wife Sue is picking up the slack by selling Definitely Not Tupperware to other women in the area, but she’s not happy, either. Youngest son Bill is dealing with a bully (who has an alcoholic father), teenage Kevin wants to be a rock star and little Maureen is on track to be a computer genius…if the adults around her give her that chance in time. The program features humor and pathos in equal measure, amplifying the effect of each.

Mr. Price and the rest of the writing staff have been extremely friendly and accessible on Twitter. At one point, they tweeted out the index card-plan they made to plot the course for Season Two. Mr. Price was kind enough to let me share it with you:

So, there are obviously spoilers if you zoom in and read all of the beats the staff laid down. On the other hand, we’re writers. We can enjoy literary works on two levels: that of the craftsman and that of the audience member.

What should we take away from this rare glimpse behind the scenes?

- Each episode (or chapter, if you’re writing prose) has emotional consequences. Look at the first cards under 201, 202, and 203. Frank is “hopeful,” then events leave him “devastated,” and then he “bottoms out.” Your story must have meaningful stakes that result in emotional change. Frank Murphy’s story does not result in earth-changing geopolitical consequences, but the events of the story have a big effect on him and his family. And that is enough.

- The writers plan arcs for each of the characters. Think of Dickens. Or The Simpsons. Each character is a fully vested presence in the world of the story. Accomplishing this goal is not easy, but sometimes, all you have to do is give characters a small moment of emotional truth. In Season 2 of F is For Family, Frank is so desperate for work that he gets a job filling the vending machines in public places…including the machines he once walked past at Mohican. His new boss is Smokey, an African-American gentleman who expects hard work and hopes to avoid his wife. Smokey could simply be a stock character, but the writers go deeper with him on a few occasions. At one point, Frank screws up, which should cost him the job. Frank goes to great lengths to fix the mistake. Smokey subsequently lets down his emotional guard and has an oddly sweet moment with Frank. Two people from very different backgrounds grew closer in understanding. (I’m tearing up here!)

- The writers fill a wall and put their whole story in front of them! I am not a big fan of over-outlining, but my work has gotten much better since I broke down each beat one by one before beginning my most recent book manuscripts. You’ll notice that the F is For Family team does not lock themselves into every single beat…the index cards can easily be removed or changed. The point is to have the shape of the story in your mind in a coherent way. The finer details, of course, will appear as you sculpt the work.

F is For Family is a show that is steeped in love. Sometimes that love is difficult and expressed in…confusing ways, but the Murphy family is all about love. The people around the family are also (generally) decent human beings. Being set in the 1970s, the writers have an obligation to represent the time with verisimilitude. (The appearance of reality in fiction.) One of the characters the Murphys see on TV is Tommy Tahoe, a Dean Martin manque who sings horribly misogynist songs about subjects like telling your wife to keep her mouth shut.

Everyone who reads this, of course, is a decent human being and would never think something like that about women, but that’s the point. For better AND worse, Tommy Tahoe would never be allowed on TV today. But this is the kind of entertainment that was mainstream in the 1970s. Have you ever seen one of the good, old-fashioned roasts? These stars, all of whom love each other, tell the most racist and sexist jokes you can imagine. But it’s all about togetherness and sharing a night together.

Mr. Price and his writing staff are surely great people, but did the right thing in presenting a heightened version of the 1970s as it was, not as we would like it to be. Another recurring element of F is For Family is Frank’s favorite show: Colt Luger. As you might expect from a crime-solver whose names are both guns, Colt is a hypermasculine crime solver who is not as…enlightened as we are. Example:

These kinds of shows were popular in the 1970s and reflect the time in which they were made. When you’re a storyteller, you must be more faithful to the story and the characters than you are to your own feelings. Otherwise, you’re not telling an honest story. You’re just giving a lecture.

Which brings me to one of the most beautiful parts of F is For Family: it’s very deep, but doesn’t force you to engage with it on that level if you don’t want to. In the contemporary parlance, Frank and Sue are struggling with gender roles placed upon them by themselves and by society. Frank’s neighbors are slightly cautious about the African-American who pulls up in front of Frank’s house. Maureen wants to build computers and Frank just has a little hold-up in his head that prevents him from giving his daughter what will make her happy. In a particularly sad Season 1 episode, Frank argues with Sue and calls the younger son Bill a “pussy.” Bill spends the rest of the episode sorting through his identity and how he wants to express it. So you could easily write college papers about F is For Family.

But most of all, the show will make you laugh and make you feel. What else could you possibly want in a work of fiction?

Television Program

Bill Burr, F is For Family, Michael Price, Netflix

If you have laughed while watching TV sometime in the course of the past forty years, you likely know the work of Ken Levine and his writing partner David Isaacs. Cheers. Frasier. Wings. M*A*S*H. For the love of Springfield, Mr. Levine created the Capital City Goofball!

Mr. Levine has also spent a great deal of time teaching other writers. For the past decade, he has been dispensing daily stories and truth on his blog, By Ken Levine. His podcast Hollywood & Levine, as of this writing, is about to premiere and will, no doubt, be a must-listen. Continue Reading

Television Program

Cheers, David Isaacs, Frasier, Ken Levine, Lilith

A sentence that is as unlikely as it is true:

Better Call Saul is really giving Breaking Bad a run for its money in terms of quality.

The former is the prequel series of the latter, of course, focusing on the character of Saul Goodman, who was originally Jimmy McGill, a man who struggles to get respect from most people in his life. Vince Gilligan and Peter Gould have added a surprising amount of pathos to the character who was essentially the comic relief in Walter White’s tragic tale. Jimmy’s brother Chuck (played by the always fantastic Michael McKean) is a legal genius and will always see his little brother as the screwup he was in his twenties. Instead of playing in the major leagues like his brother, Jimmy must do his best to hang in the lowest levels of the legal profession in spite of the hard work he put in to overcome those problems.

The program is fantastic and worth a watch, but I have a nit to pick. One of the lessons I absorbed from the great Lee K. Abbott is to do as much as possible to avoid allowing a factual error to dissipate the spell that we cast over the reader. If you have a character use a ballpoint pen in 1934, people like me will no longer be immersed in your world. Why? Ballpoint pens didn’t reach the masses until at least a decade later. Instead of thinking about your story and your characters, I’m bringing up my mental encyclopedia.

I just had the same experience with “Cobbler,” the episode of Better Call Saul that debuted on February 22, 2016 and was written by Gennifer Hutchison and was directed by Terry McDonough. The episode is well-written and well-directed and well-acted. Of course, but there’s a lesson to be learned.

One of the subplots in “Cobbler” centers upon Mike Ehrmantraut, a “fixer,” trying to retrieve baseball cards that were stolen from his foolish former client, Daniel. Instead of keeping a low profile after selling prescription drugs to a gang, Daniel uses his new income to buy a gaudy yellow Hummer H2 that is painted up in gaudy hot pink flames, a color scheme so gaudy that even the 1980s would be embarrassed. And the spinners on the rims! Ugh.

Daniel foolishly declines Mike’s services, which results in his connection learning his home address. As you might expect, the drug dealer simply burgled Daniel’s house, stealing his remaining supply of pills and his extremely valuable baseball cards.

Now, I happen to be a bit of a baseball card collector; I certainly know my stuff about cards from the 1980s through the early 1990s, as that is when I was allowed to have little else on my mind but baseball and books. (Good times.) So Mike negotiates to get the cards back. Daniel said in the previous episode that he had some valuable rookies and some Mantle and Aaron cards…the kind of thing I’d expect to see if we’re talking valuable cards. Daniel said that the cards are in “top loaders,” which makes sense, though I would have expected that a well-heeled collector would have his cards slabbed by PSA or a similar service. But close enough.

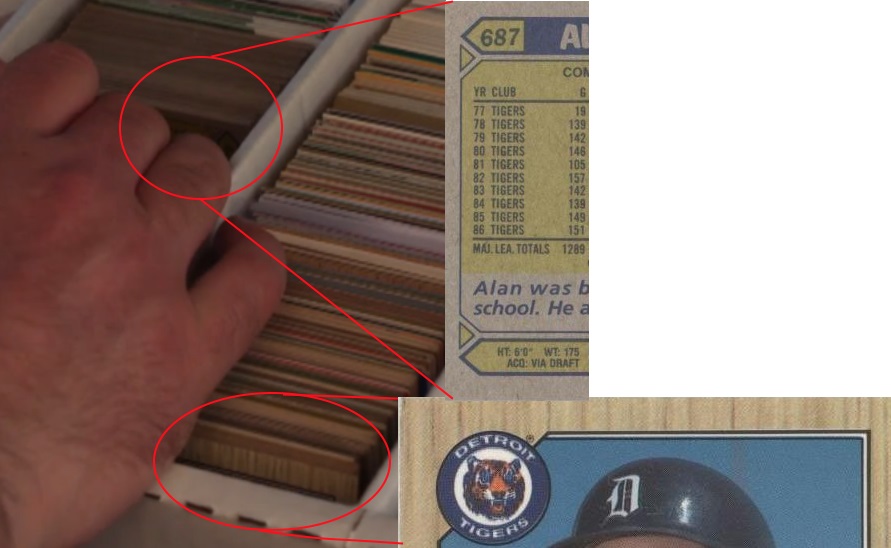

Okay, so I’m watching the cool scene from “Cobbler.” Daniel is trading his gaudy Hummer for the cards. I am loving Mark Proksch’s great acting; how can Daniel not understand the very basics about criminal stuff? The baseball card fan in me sees the boxes…there are four monster boxes and a couple even larger boxes. Impressive!

The henchmen put the cards in Mike’s trunk. Of course, Daniel double-checks to make sure everything is there. Me? I’m excited to see if he has an Al Kaline rookie or any beautiful 1956 Topps cards or maybe even some earlier Bowman stuff! What could be in there? Remember, these are extremely valuable cards that are worth enough money to drive a plot in a show about drug dealers and attorneys!!!

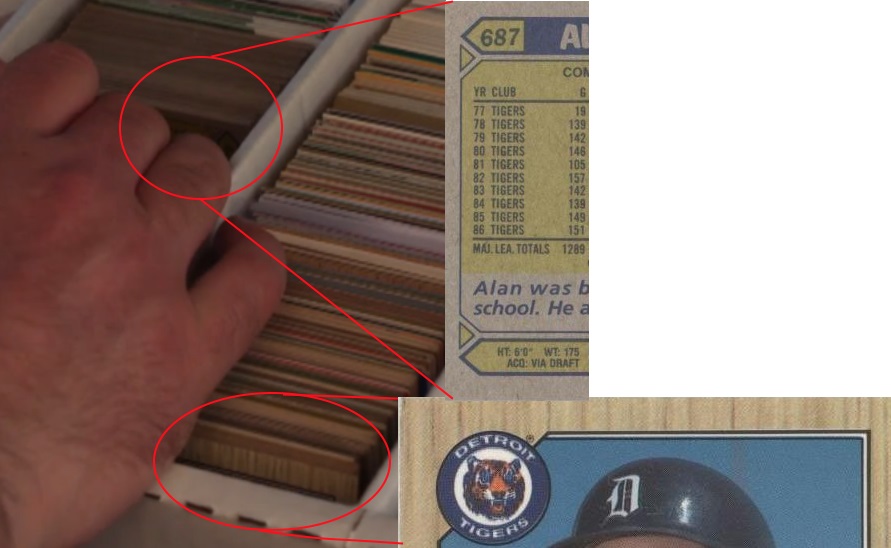

Daniel says, “Aaron…there’s Jeter…” The director cuts to an insert shot of Daniel flipping through the cards:

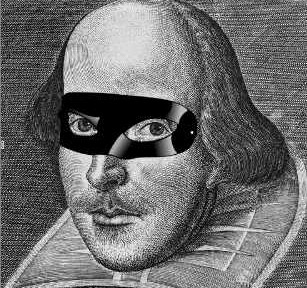

Wait. What? No. Just. No. That is NOT what a box of extremely valuable cards looks like. That’s what a box of commons looks like. None of the cards are in top loaders or in slabs. There are clearly stacks of cards from the same sets just slapped together in a hodgepodge. Even worse, these are clearly cards that are worth next to nothing. Look at the bottom right; there’s a few packs’ worth of 1988 Donruss cards. See? Look at the borders:

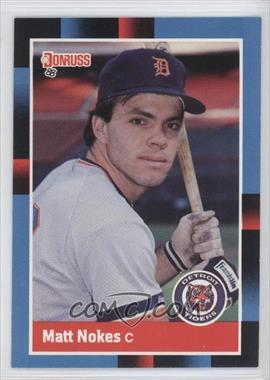

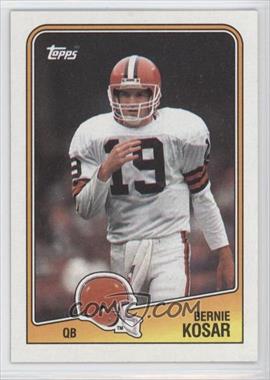

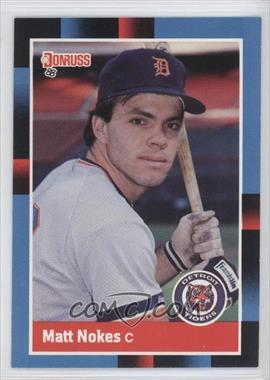

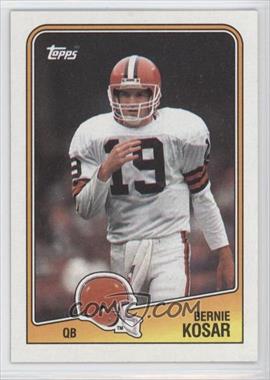

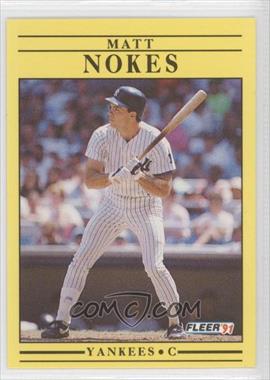

Even though Matt Nokes is my favorite player, the card is worth no more than a few cents. Certainly not enough to get Mike Ehrmantraut out of bed. And look at the card peeking out under Daniel’s left thumb. It’s a 1988 Topps football card:

Even though Matt Nokes is my favorite player, the card is worth no more than a few cents. Certainly not enough to get Mike Ehrmantraut out of bed. And look at the card peeking out under Daniel’s left thumb. It’s a 1988 Topps football card:

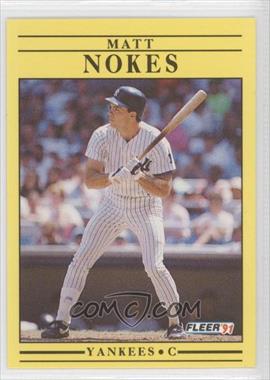

And it looks like the cards above the 1988 Donruss are from 1991 Fleer. Notice the maximum yellow:

Here’s the problem. The production designer and the prop people and all of the other brilliant behind-the-scenes folks put together a show that makes me believe everything is real. I love being immersed into the seedy side of Albuquerque. These professionals even managed to find or make the perfect watch and shoes for Daniel’s character; the match the ugly paint scheme of the car and say a lot about his character.

Here’s the problem. The production designer and the prop people and all of the other brilliant behind-the-scenes folks put together a show that makes me believe everything is real. I love being immersed into the seedy side of Albuquerque. These professionals even managed to find or make the perfect watch and shoes for Daniel’s character; the match the ugly paint scheme of the car and say a lot about his character.

Look! Daniel even seems happy to get back a bunch of 1987 Topps. I love that set. It’s probably my favorite. But no drug dealer is going to steal your 1987 Topps cards in hopes of making money. You will not get any money for these cards. Topps printed about 11 trillion of them.

There are much graver sins that a writer can commit, but I think this is a good illustration of how we must make sure we are presenting the world as it is and was in our fiction. Instead of spending the past 45 minutes watching the episode of Better Call Saul and ruminating on how great the program is, I wrote this post.

I’m sure that Mr. Gilligan and Mr. Gould and Mr. McDonough and Ms. Hutchison would all agree with me that storytellers have many things in common with magicians. We cast very different incantations, but they are spells nonetheless. Let us do nothing to our audiences to make the effects of that spell fade.

Television Program

Better Call Saul, Gennifer Hutchison, Terry McDonough

As the written word has lost some of its relevance in a sea of glowing screens and an exponential proliferation of Real Housewives that threatens to overrun the United States World War Z style within the next few years, it may be hard to remember that writers were once considered celebrities in their own right. Sure, a lot of people know who J.K. Rowling is, but I can’t help but pine for a time when wordsmiths had a higher profile. Stephen King even did a commercial for American Express!

Writers have an unlikely hero in the new host of The Late Show: Stephen Colbert. In an attempt to distinguish himself from the two Jimmies (Kimmel and Fallon), Mr. Colbert is taking a slightly more intellectual route with the program. Inviting an author onto the show instead of the fifth lead in the latest Michael Bay movie must drive the network crazy? After all, who wants to see an interview with some writer?

We do, of course. In the past couple months, Mr. Colbert has given network air time to writers such as Doris Kearns Goodwin, Stephen King, Jonathan Franzen, George Saunders and Elizabeth Gilbert. George Saunders even read a short story to Mr. Colbert (and the audience). On national television! Look:

Why is it significant to see writers on Colbert instead of Charlie Rose? Why isn’t it good enough that Diane Rehm and Terry Gross interview their fair share of writers? Look, I love the Charlie Rose/NPR kind of interviews, too. The sad truth is that if we want to bring new readers into our circle, we need to seem like lots of fun. Terry Gross is brilliant and fascinating and must be one heck of a party guest, but Omarosa, a woman who breaks into tears when hit on the head with a gram of plaster, will always get more attention in our contemporary culture. Mr. Colbert’s Late Show is a bright carnival of music, humor and energy. When people see Jonathan Franzen participate in the carnival, viewers can see that reading is not necessarily homework and they might enjoy shifting some of their Candy Crush time over to reading.

Do tune in to the Late Show live, but here are some clips of Mr. Colbert interviewing some of our colleagues:

Novel, Television Program

George Saunders, John Irving, Stephen Colbert, Stephen King

You thought Community was dead, didn’t you? The show has been written off several times because it requires a little more of the audience than just staring at a screen. You never need to worry about Kardashians going away:

See? You don’t even have to move your eyeballs! You don’t learn anything! Your mind and soul can remain asleep while you watch.

Community has been in danger since it premiered because the show invites you to move your eyeballs and to process what is happening in the show. The program also offers you something in return for a little bit of attention. The same can’t be said of the Kardashians. After five seasons on NBC (one of them without the brilliant creator Dan Harmon), Community has moved to Yahoo! Screen and has made a change or two.

“Ladders” establishes the new new new new new normal at Greendale. Writers Harmon and Chris McKenna have a bunch of exposition to drop for us. As is the case with many previous episodes, the writers begin with a voice over from the Dean: the audience is reminded of which characters remain on the show and are refreshed with respect to character. (Winger is still a bit selfish; he parks in an electric-only spot and just throws the charger in the window.) Britta is homeless, Abed is still creating, having written the Dean’s announcement. The inciting incident of the episode (and the bringer of change to Greendale) is Annie’s failure to address the mountain of Frisbees on the roof. One more disc makes the roof collapse, forcing the Dean to bring in a humorless penny-pinching manager. “Frankie” has as much trouble adjusting to Greendale as the study group has adjusting to her. She takes the booze out of the teacher’s lounge and makes a million other awful changes.

Abed, perhaps jarred by all of the change around him, begins to question his meta-entertainment-centric worldview. Winger, Annie and Britta start a speakeasy in the basement in response to Frankie’s rules. As you can imagine, she discovers the incredibly illegal bar and leaves, believing she doesn’t fit in at Greendale. As you can further imagine, removing all boundaries from Greendale results in big problems, not the least of which is combining alcohol and “a class called ‘Ladders.'”

After the predictable ladder accident, the gang brings Frankie back, changing what it means to be part of the family at Greendale.

See? The summary demonstrates that Community is a little bit complicated; the show is certainly “harder to get into” than many other pop culture creations. Everybody Loves Raymond is very easy to understand; that’s not necessarily a bad thing. The husband is dumb, the wife is mean, the in-laws are a pain. Got it. (And the creators got hundreds of millions of dollars…) I’m not just talking about TV shows; it’s very easy to engage the outrage du jour. (OMG. Lindsay Lohan called her friends Kanye and Kim the “n-word” in a friend way. Why don’t I write a 100-word post about it and tack on several ads instead of wasting my time writing a meaningful essay?) It’s much harder, on the other hand, to create real art.

Dan Harmon and Community exemplify what I love about my favorite creative people. Harmon and those around him push themselves to try new things, no matter how hard or annoying they are. I’m sure that the paintball episodes of Community were a massive logistical pain in the behind for everyone involved. Instead of simply planting actors on the stage, the cast and crew covered the set-and each other-in paintballs and had to have everything back to normal for the next episode. It was likely a huge, costly inconvenience to find the artists and resources necessary to make the animated episodes of the show. Can you comprehend how many hours went into composing and choreographing songs for the musical episode?

I suppose this point cuts to the quick of what bums me out about some writing that least engages me. People are welcome to write whatever they like, but what’s the point of writing the same story a thousand times? With the same exact characters? In the same exact setting? We become writers to explore people and ideas, not to repeat ourselves a thousand times, right? At least, that’s the way I approach art.

As a further example, I’ll use Alison Brie, the very talented actress who portrays Annie in Community. Annie is bright and bubbly and vulnerable. Ms. Brie also plays Trudy Campbell on Mad Men, a character who is (increasingly) the opposite of Annie. See?

Ms. Brie is a stellar actress and clearly understands a wide range of complicated characters and their emotions. Writers get to create and inhabit all of the characters they want…and they don’t even have to sit through hair and make-up. Why deprive yourself of any creative opportunity?

“Ladders,” like many episodes of Community, is interesting for the way it interacts with the real world. That whole “meta” thing. The audience is (likely) aware that the show has gone through some changes; Mr. Harmon and Mr. McKenna address these changes in the context of the show. Abed, the narrative-obsessed character, describes the changes in the characters and in Community itself:

I’m worried you’re not distinctive enough from Annie both in terms of physicality and purpose. I can’t determine if you have any specific flaw, quirk or point of view that makes you a creative addition to the group. My umbrella concern is that you as a character represent the end of what I used to call “our show,” which was once an unlikely family of misfit students and it is now a pretty loose-knit group of students and teachers, none of whom are taking a class together at a school which, as of your arrival, is becoming increasingly grounded, asking questions like “how do any of us get our money,” “When will we get our degrees?” and “What happened to that girl I was dating?” instead of the questions I consider more important like, “What is real?” “What is sanity?” “Is there a god?” “Where’s that Pierce hologram?”…

Abed is referring to the changes happening around his character and he’s also guiding the audience through the transition the show is making. What’s the primary point to take from Abed’s thoughts in this episode? Writers must evolve as a result of external and internal factors. Do we get better with every paragraph we put down? Sure. Do our skills improve each time we read a classic book or think about a classic film? Of course. We must also challenge ourselves in order to honor our gifts. Dan Harmon and his team must deal with a million external challenges: changing budgets, network changes, contractual availability of actors…it must be a nightmare. Mr. Harmon and his team turn these challenges into opportunities as often as they can; many thanks to Yahoo! for bringing Community ever closer to #sixseasonsandamovie.

Television Program

Community, Cool Cool Cool, Dan Harmon, Dreamatorium, Yahoo! Screen

As anyone who knew me as a youngster can attest, I grew up in a haze of solitude and nerdiness. Not this nouveau nerdy, the kind where a person as attractive and as popular as Kaley Cuoco claims to be a huge geek because she likes The Big Bang Theory. I was honest-to-goodness, all-my-time-alone-in-my-room nerdy. Many of my early memories that have survived the defense mechanism wipe I’ve done on my brain relate to Star Trek in some way. I love The Next Generation and how “The Drumhead” taught me lessons we’d forget completely after 9/11 and still haven’t rediscovered. I loved reading the tie-in books and someday dreamed that I could write those books. (Those dreams have not come true.) I loved reading about the science fiction fandom that transpired before I was born, spending countless hours reading and re-reading the whitewashed Gene Roddenberry biography popular at the time.

As a young person, I had only a hint of what I would love most about Leonard Nimoy. There was no Internet, but the science fiction fan magazines often mentioned Mr. Nimoy’s side projects: his photography, his stage work, the films he directed. Mr. Nimoy possessed a quiet dignity that radiated through the screen. Behind that dignity, I think, was Mr. Nimoy’s ultimate truth: he loved human creativity and exercised his own in ways to which few of us can aspire.

We should all aspire to follow Mr. Nimoy’s lead and to manifest our creativity in the ways suggested by our Muses.

Mr. Nimoy did all of the following (and more) in his eighty-three years on Earth:

Acted on Broadway and in regional theaters.

Became a highly respected photographer who undertook a number of different projects examining some aspect of humanity or faith.

Published seven books of poetry and dabbled in putting some of that work online.

Directed feature films of the Star Trek and non-Star Trek variety.

Spent over 60 years in acting, from the near-infancy of television and the insanity of Hayes Code Hollywood to working on The Big Bang Theory and in video games.

Released music when he darn well felt like it.

Now, don’t feel bad if you don’t have the same kind of insanely broad ambitions. I am one of the people, however, who admires that Mr. Nimoy was curious about working in all kinds of forms and with all kinds of stories. I think it’s safe to say that Mr. Nimoy would be happy if contemplating his death inspired someone to write a song for the first time. Or to take up photography. Or to perform any creative act that they had previously avoided as a result of self-doubt or fear of what others would think.

Mr. Nimoy gave his audience what they wanted while remaining true to his artistic impulses.

In 1975, Star Trek was in syndication and its cast was in an interesting position: they were part of American pop culture, but weren’t exactly raking in the big bucks. The first Trek movie wouldn’t come out for a few years. It must have been an interesting and frustrating time for many of these folks. Mr. Nimoy published a book entitled I Am Not Spock. The book was not a repudiation of the role, but an affirmation of the author’s own identity.

Though he was frustrated by the typecasting he did receive, Mr. Nimoy understood that there are worse things than being beloved by millions of fans and respected by your professional acquaintances. Leonard Nimoy walked the line between art and commerce in way few have managed. What’s the balance between selling out artistically and selling enough to provide for oneself and one’s family? Mr. Nimoy gave us what we wanted: Mr. Spock, Three Men and a Baby, countless appearances at Trek conventions, In Search Of… He also gave us what we didn’t know he wanted: a Kabbalah-inspired photography project, Leonard-Nimoy-in-Equus, books of Nimoy poetry.

I worry that the “literary” community needs to do a better job at this balancing act. I hate the need for money as much as the next writer, but cash makes the world go around. Mr. Nimoy understood the audience principle and that if we fill enough seats with good work that is also popular, we can keep doing the good work that isn’t as commercially viable.

Leonard Nimoy made himself a part of every creative endeavor of which he was a part.

Like I said, I was a big-time nerd. I learned long ago that Mr. Nimoy accessed his Jewish roots when required to devise a Vulcan salute. The incredibly familiar hand gesture is derived from a blessing performed by kohanim. Don’t you find it beautiful that an ancient tradition will last in perpetuity, brought into the popular consciousness in an ambitious narrative that reflects mankind’s desire to explore the universe?

I don’t happen to be Jewish, but I love that Mr. Nimoy made use of what was familiar to him while helping to create a work of art that was not completely his own. How does your own work reflect who you are? Not necessarily in terms of easily defined categories or the obvious manners in which you identify yourself by group, but in the specificities of your past? Do you have a character who speaks like your long-dead great-grandmother? Have you written about shoemaking, the profession of an even more distant relative? What are we but a collection of stories; how do your long-buried and secret stories relate to the narrative of you and those you produce?

A life is like a garden…

Mr. Nimoy and I are very different artists; I’ve never had ambitions to act and I have no delusions that my voice could earn me a place behind a professional microphone. But I’ve always wanted to live the kind of life that Mr. Nimoy enjoyed: an existence packed to the brim with expression, filled with creative people and dedicated to examining the endless wonder to be found on Earth and beyond.

Television Program

Leonard Nimoy, Star Trek

Friends, David Chase’s HBO program The Sopranos is widely hailed as one of the shows that ushered in the latest “golden age” of television. James Gandolfini portrayed Tony Soprano, a New Jersey man who spent his time caring for his family and his waste management business. Oh yeah…he was also a big-time player in the Jersey mob.

The Sopranos ran from 1999 to 2007 and has influenced countless dramas that followed. (Breaking Bad, in particular.) The final episode was highly anticipated and Mr. Chase did his duty, giving the story an ending that viewers wouldn’t soon forget:

Many were confused by the abrupt cut to black. Others figured there was a problem with their cable connection. The reaction bummed me out a little; I loved that Mr. Chase ended the show on his own terms and that he made an artistic choice.

Didn’t Mr. Chase experience every writer’s dream? Millions of people were hanging on his every word and have since spent the better part of a decade deciding what the piece means to them. “Masterofsopranos” offered my favorite analysis. Jamie Andrew produced a thoughtful explanation for Den of Geek!

Well, Mr. Chase offered some after-the-fact clarification with regard to Tony’s true fate. I’ve linked an article, but you know what? It doesn’t matter what Mr. Chase thinks. He was kind enough to give us the work and it now belongs to each viewer.

Now, I know that Twitter isn’t really good for much. It is, however, a means of communication and must have some intrinsic value. For instance, the great Joyce Carol Oates offered some ideas regarding the Sopranos finale that we should bear in mind:

Ms. Oates retweeted this nugget of timeless wisdom:

Writing is a double-edged sword. Writers get the pleasure of sharing creations with readers…then the writer must accept that each reader invariably makes that creation their own. We thank Mr. Chase for giving us Tony and Paulie and Christopher and Carmela and Adriana (RIP), but his act of giving also means that they now belong to us.

Did Tony get shot? Your theory is worth just as much as the impulse that guided Mr. Chase during his long hours at the keyboard.

Television Program

2007, GWS Twisdom, Joyce Carol Oates, The Sopranos

Title of Work and its Form: Penn & Teller, magic act/writers/producers, etc.

Author: Um…Penn Jillette and Teller. (Mr. Jillette can be found on Twitter @pennjillette and Mr. Teller can be found @MrTeller.)

Date of Work: The pair have worked together since 1975.

Where the Work Can Be Found: Penn & Teller have a regular gig in their theater in the Rio All-Suite Hotel & Casino in Las Vegas. If you are in the area, go and see them several times. Mr. Jillette and Mr. Teller always have a lot going on. You may be able to keep up at this Facebook page. Mr. Jillette has a STELLAR podcast called Penn’s Sunday School. Penn and Teller are always doing interesting things like this: a magical collaboration with a dance company.

Bonuses: Penn & Teller are on a lot of talk shows. Why do producers enjoy booking them? Because P&T are always interesting and they always come prepared. Here is an appearance the duo did on Letterman:

And here’s a great appearance they did with Conan.

Here is where I first took note of Penn & Teller. (At least I think that’s the case. I was pretty young.) Spy Magazine (one of the best ever) allowed the magicians to tell you how to pull a mean prank on your closest friends.

Discussion:

I’ve been a big fan of Penn & Teller for a very long time and for a number of reasons. Only in the past decade or so have I come to understand more deeply why they are so amazing and have been relevant for so long. Penn & Teller teamed up nearly forty years ago; Penn had no formal post-secondary education and Teller had a degree in Latin and taught the classics. Look at what Penn says in this Q&A starting at around 20:30:

Penn makes a very interesting point. The two men have a relationship that is primarily about respect and not love or extreme affection. In a way, the respect we have for writing partners and fellow scribes is more important than love. Respect is a sentiment that is earned based upon evidence, while love can be inspired by irrational thinking. Think about your experiences with your favorite teachers. I remember my first workshops at Ohio State quite well; I sat down in the workshop room with a great deal of respect for folks like Lee K. Abbott simply because of what he had accomplished in the literary world. Over the first few workshops we shared (and the subsequent years I got to work with him), my respect deepened based upon his skill and the way he related to everyone. That kind of sentiment doesn’t go away very easily. Compare that to a crush you had in high school; those feelings are far more precariously perched in our hearts. If you are lucky enough to work with a partner, bear in mind that the longevity of the arrangement will be determined by your commitment to the work, not to each other.

I’ve been a fan of Penn & Teller’s Bullshit for many years. I even use it in my classes because Penn & Teller are masters of rhetoric. (And why shouldn’t they be? Magicians MUST be able to convince you of all kinds of things that aren’t necessarily real.) The program is a kind of documentary series; in each episode, the pair take on an issue and point out, as they put it, the “bullshit” involved. Do I always agree with them? Of course not; no one agrees with anyone else 100% of the time. (Not even Penn with Teller and vice versa.)

As you can tell by the abrasive-to-some title, Bullshit pushes some away with its title and still others with the hosts’ strong stances on controversial issues. Some, for example, contend that there is proof that childhood vaccines have contributed to the recent rise in autism diagnoses. Penn & Teller point out very clearly that there is no science to support such a hypothesis and spend 28 minutes employing ethos, pathos and logos to dismantle the claim from all sides. Here’s the introduction to the episode:

By all means, please buy the program on DVD or stream it. Even if you disagree with Penn & Teller on this point or any other, the two men (and their researchers and co-writers) create works that result in both light and heat. Great writing (and magic) should address our intellect AND our emotions. A great book teaches us something about the world AND makes us feel something real.

Penn & Teller do a lot of dangerous tricks that you definitely shouldn’t try to recreate at home. As the duo notes, it can take YEARS for them to perfect a trick enough to perform it for a real audience. They spend a lot of time and money just PRACTICING and TRYING and HOPING that a trick will work out. If it doesn’t work out in the end, they abandon it. Is this a bad thing? Not necessarily; their infrequent failures teach them important lessons.

I love that Penn & Teller, like so many magicians, immerse themselves in the history of magic and the magic world at large. The same is true with comedians: most great comedians know everything about the field. Great writers? They are very hard to stump in a discussion about literature. Penn & Teller made a whole documentary in which they went in search of the history of “the cups and balls,” one of the basic tricks that every magician learns. This is how everyone who dabbles in prestidigitation learns their loads and steals and how to make their hands move faster than the audience’s eyes. The pair ended up in Egypt in an ancient building whose walls feature a depiction of what may be a person doing the cups and balls trick…thousands of years ago. How do they honor the tradition? They perform their own version:

Look at this beautiful essay Mr. Jillette wrote for the Huffington Post. Here is a recording of Mr. Jillette reading his essay.He was competing on Celebrity Apprentice, a program that some folks wouldn’t believe possible of creating something that is artistically beautiful. That notion was blown out of the water when Mr. Jillette and Blue Man Group decided to change what Celebrity Apprentice COULD be. During a fundraising task, most contestants will simply have a rich celebrity friend bring by a big check. Everyone oohs and ahhs about selling Gary Busey’s painting for $50,000 and boom. Done. Instead, Blue Man Group, the entertaining and experimental performance art group, decided to bring in money, but to do it their way. The Blue Men brought in money, to be sure, but did so in a giant balloon and accompanied by eccentric pomp and circumstance. The balloon was then burst, creating yet another sight that most people have never seen: legal tender fluttering around the streets of New York. Life, they seem to say, should be lived for enjoyment and to glorify beauty.

For whatever reason, Penn & Teller are sometimes self-deprecating when describing themselves. They’re not just carny/renaissance fair folks; they’re smart men who devote themselves to all of the many things that are important to them. Mr. Jillette has written several books, some with Mr. Teller. Mr. Teller directs plays and makes use of his magic skills when appropriate…I’m sure that Macbeth’s dagger looked great onstage.

Mr. Teller inspired me in a very cool way. In 1997, the gentleman published an essay in The Atlantic. In high school, Mr. Teller read “Enoch Soames: A Memory of the Eighteen-Nineties,” by Max Beerbohm. Soames is a poet who wishes to know if his work will have any effect on literary history, whether all of his modest scribbling will be in vain. The Devil (of course) offers him a deal: Soames will spend eternity in Hell in exchange for a trip to the Round Reading Room of the British Museum in 1997, where Soames will see evidence of his legacy.

Now, I don’t want to ruin both “Enoch Soames” or Mr. Teller’s piece of creative nonfiction. If you read the Atlantic article, you will see the same kind of glorification of art and the artistic impulse that Mr. Jillette described in his piece. Why do I mention all of this? The Atlantic piece struck me deeply and a great story idea popped into my head, which I promptly wrote. I usually hate the stuff I write (a defense mechanism?), but this story turned out pretty well, perhaps the best I’ve ever written. What is the big takeaway? Artists have chosen a difficult life, but a very rewarding one. After all, we are fortunate enough to be the people who bring beauty and joy and magic to the world.

I’ll conclude with another thing of beauty from Mr. Teller. When he was a young man, Mr. Teller came up with a trick he calls “Shadows.”

It really is a very graceful and simple piece that clearly means a lot to Mr. Teller. Like a poet who keeps a favorite poem in his or her reading rotation for years, Mr. Teller still performs “Shadows.”

You never know which of your works will endure the longest or will mean the most of you. The lesson, I suppose, is to throw yourself headlong into creating and improving and learning and hoping that something good will happen for you.

What Should We Steal?

- Respect your writing partners, colleagues and teachers more than you love them. Respect is hardier than love.

- Compose works that result in both heat and light. Think about all of the works that have survived the centuries…they all engage readers on a number of levels.

- Devote yourself to your work and to your discipline. Bear in mind that you belong to a long line of writers. Leave your own spin on the field, but honor the fraternity as well.

- Find the art in everything you do and make sure your life is a performance. There’s great beauty in extreme weather and mundane supermarket browsing.

If you found my analysis useful or enjoyed my writing style, would you consider checking out Great Writers Steal Press, where I have published some eBooks of the fiction and nonfiction variety? Just head over to books.greatwriterssteal.com, where reading is not homework!

Television Program, Uncategorized

1975, Penn & Teller

Title of Work and its Form: Season Four of the Television Program Arrested Development

Author: The program was created by Mitchell Hurwitz (on Twitter @MitchHurwitz). Much of the original creative team joined him, including Jim Vallely.

Date of Work: The episodes premiered on May 26, 2013.

Where the Work Can Be Found: The episodes can be found streaming on Netflix. (Thank you, Netflix!)

Bonuses: Here is The Onion A/V Club’s ongoing coverage of the program. Here is a massive chart from NPR that chronicles the running jokes in the program.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Characterization

Discussion:

Well, friends, you knew this essay was inevitable. I’ve already espoused my deep love for the first three seasons of Arrested Development and the fourth season does nothing to tarnish that legacy. As for a summary? The fourth season takes place several years after the show ended on Fox. We learn how each of the characters spent their time. George Maharris went to college and studied abroad in Spain. (He did a little bit too much studying, perhaps.) Maeby went to high school again and again. Tobias and Lindsay bought a house they couldn’t afford and traveled to India. Michael built Sudden Valley and lost everything. Lucille goes on trial for stealing the Queen Mary. George Sr. becomes a sweat lodge guru…it’s really hard to summarize what happens.

Hurwitz and friends had a massive challenge in front of them. Fans of Arrested Development had very high expectations for the new episodes. The new season had to be written in such a manner that filming would coincide with the actors’ busy schedules. There are many Bluths whose stories needed to be told in addition those of the tangential characters we all know and love. What is the main reason that Season Four succeeded? It’s the same reason that any extended narrative succeeds: the characters are deep and the characters drive the humor.

Think of just about ANY great extended narrative. Harry Potter. Lord of the Rings. Cheers. All in the Family. Seinfeld. The Dick Van Dyke Show. The situations and the humor (there IS humor in Harry Potter) emerge from the characters; it isn’t foisted upon them. Mr. Hurwitz and company, in a way, didn’t write the new season as much as they figured out what the characters would be doing. Think about DeBrie, one of the new characters. She’s an STD-ridden former actress with a heart of gold. Tobias meets her at the Method One clinic, where she’s doing one of her monologues. (Tobias is a bad actor, so it makes sense that he would confuse NA-type confessional as an actor plying her craft.)

After her character has been well-established, Tobias tries to get her back into acting by saying: “No, DeBrie, come on… Don’t you want to get back on that horse?”

To which DeBrie replies, “Even better!”

It’s not a complicated punchline, but the humor is derived from DeBrie’s constant desire to use narcotics.

Think about the extended scene in the first episode in which Michael, Maeby and George Michael are trying to decide how the voting-out procedure will go. If we didn’t know the characters, we would probably find the scene alone pretty boring. Instead, we love the scene because so much is going on and it’s derived from the characters.

- Michael doesn’t understand how pitiful he has become and that his son wants to get rid of him.

- George Michael is trying to break out of the Bluth mold and to get some independence from the family, a difficult proposition. He’s even named for his grandfather and his father. He wants to seduce Maeby (and was about to when Michael first burst in).

- Maeby wants to get FakeBlock going (if I recall correctly) and wants to make pop-pop with George Michael and probably wants to eliminate reminders of her inattentive parents.

The audience understands the emotional stakes for the characters, so they care and flinch and laugh at the same time.

Another reason that the new season is so great is that Mr. Hurwitz gave us exactly what we all wanted without giving us exactly what we wanted. It would have been very easy for him to create a less complicated version of Arrested Development in order to please the maximum number of people. Instead, Hurwitz gave us what we REALLY wanted: a work that is complicated and requires that the viewer pay attention.

Season Four will age very well because Mr. Hurwitz followed his muse in the confines of his real-world restrictions. I think I read in an interview that he could only get the whole cast together on-set for two days. The budget for the new episodes was likely lower than the budget for the Fox episodes. Therefore, Mr. Hurwitz changed the Arrested Development format in a way that he felt was true to the characters and his goals on the original show. Had he not experimented with the Rashomon structure and each-character-gets-a-short-film idea, the art would suffer. It’s no longer 2006, so he couldn’t pretend as though he were making whatever the original Season Four would have been. He created the show that was dictated to him by his muse.

One of the million things I’ve always loved about Arrested Development is how clear it is that everyone on board bought into making the show great. It’s hard to make great comedy if you are being “reverent.” Comedy is, by its nature, irreverent. (That’s why it is sometimes difficult to find good comedy by conservatives. Sorry, but it’s true. Prove me wrong?)

There are many times in Season Four in which the writers are making good-natured jokes about the actors. For example, the acclaimed director Ron Howard gets a “hat haircut” and calls all of his barbers Floyd. The design accent above his office door is a ballcap. (And Brian Grazer’s office next door is sculpted to look like Mr. Grazer’s trademark hair.) Rocky Richter sits in for his brother on Conan and makes a joke about Ron Howard’s hair. Mr. Howard could easily have had any of these details excised, but he didn’t. Why? Because he is laughing WITH the writers and the audience and because he is apparently as emotionally secure and as happy as he should be. Mr. Howard has reverence for storytelling and comedy and pleasing the audience and doesn’t revere himself in an unhealthy manner, all of which benefits the work as a whole. Isn’t this attitude one of the marks of a true artist?

What Should We Steal?

- Derive humor and drama from your deep, complicated and human characters. A story is not as compelling if the reader can see the hand of its creator. Instead, the reader should feel that he or she has been offered a window into another world and a glimpse into the lives of real people.

- Write to satisfy your muse, not your audience, imagined or real. You’re more likely to impress the audience if you impress yourself first!

- Allow yourself and your treasured characters to be the butt of the joke. Within reason, your priority should be to serve the work, not yourself.

Television Program

2013, Arrested Development, characterization, Her?

Title of Work and its Form: “Best Man for the Gob,” an episode of Arrested Development

Author: Written by Mitchell Hurwitz (@MitchHurwitz) and Richard Rosenstock and directed by Lee Shallat Chemel.

Date of Work: The episode originally aired on April 4, 2004

Where the Work Can Be Found: The episode is included in the Arrested Development Season 1 DVD package that you should have on your shelf. You can also stream the episode on Netflix.

Bonuses: Here the episode’s page on The O.P., a very cool fansite. Here’s a Tumblr filled with animated GIFs from the show. (A necessity on par with food and water and air.)

Here is the pain Tobias went through after Lindsay and Maeby quit the band and he learned about the conference’s policy regarding parking validation:

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Characterization

Discussion:

It’s hard to summarize any episode of Arrested Development because of the simple fact that SO MUCH HAPPENS in all of them. In this first season classic, accountant Ira Gilligan points out that money is missing from some of the Bluth Company’s accounts. Gob is going to have a bachelor party to celebrate his union with Wife of Gob; George Sr. takes the opportunity to turn it to his advantage. What’s the plan? The bachelor party will be an excuse to make Ira think he killed a narcoleptic stripper, leading him to leave the country and end his investigation of the theft. Tobias, Lindsay and Maeby are getting the band back together. Dr. Fünke’s 100% Natural Good-Time Family-Band Solution played lots of wellness conventions, informing listeners about the side effects of drugs such as Teamocil. (“There’s no I in Teamocil…at least not where you think…”) Buster is thrilled about the unlimited juice (fake blood) at the bachelor party and Michael, offended at being passed over as Best Man, takes George Michael on what he intends to be a fishing vacation. But poor George Michael wants to spend time with Maeby and play wood block in the band because he’s such a good percussionist. The bachelor party goes wrong, of course. Ira’s a designated driver, so he’s not drunk. He vows to testify against the Bluths. The kicker? Ira’s the one who stole the money.

One of the greatest strengths of Arrested Development is its dedication to giving secondary and one-time characters full citizenship in the story. We’re never going to see Ira Gilligan again, but we learn a great deal about him. He’s annoyed by working with incompetent people, he puts up with a lot of abuse (being called “Gilligan”), he seems like a moral person (until the reveal), he’s good at his job… Ira Gilligan is a real character and you can imagine what happens to him after the episode is over. Now, you can’t make EVERY character in your piece a complete citizen. Think of Law & Order; sometimes you need a witness who isn’t a full character to simply point out where the bad guy ran. But look at this list of secondary characters from Arrested Development:

- Wife of Gob

- J. Walter Weatherman

- Steve Holt!

- Bob Loblaw

- Stan Sitwell

- Sally Stickwell

- Warden Gentles

- Tony Wonder

The list goes on and on. Even though these people are only given a few minutes of screen time, the writers, directors and actors make them real, well-rounded people. Why is this a great thing? People, just like characters, don’t exist in a vacuum. When you write a story, you’re creating a world and are just choosing to focus on specific characters from that world. In spite of this focus, your protagonist inhabits a reality filled with people who are protagonists of their own stories.

One of the many ways that Arrested Development sets itself apart from other programs is that the characters are extremely unlikeable in a number of ways. Each Bluth is selfish and is usually willing to cheat the others to get what they want. George Sr. embezzles from his business. Lucille dislikes most of her children and has smothered Buster so much that he can’t function on his own. Tobias refuses to get a job or to acknowledge the truth about himself. Lindsay is insanely shallow. Gob lies to women (a lot of them) and ignores his son. Why don’t we hate the Bluths? Their misadventures seldom cause terrible damage to the lives of others and, just like a real family, there are moments of genuine love between them. (Just think of the Lucille intervention that turned into one of their best-ever parties.)

Your audience will see the humanity in the worst character if you depict them in full. Tom Perrotta’s Little Children depicts a child predator in an appropriately sympathetic light. You love your crazy uncle, even though he’s crazy. We can appreciate unpleasantness in the people we read about so long as we have some clue as to WHY they are the way they are. (Lucille just wants her childrens’ love, Gob doesn’t know how to love, George Sr. is really a henpecked husband…)

Arrested Development stole a lot from Seinfeld in the structure of its plots. The Bluths spend a lot of time apart in the rest of the episode. The bachelor party climax of the episode, however, brings together many of the elements from the episode. Gob’s relationship with his wife, the theft of the money, the strife in Tobias’s family, Buster’s addiction to juice…they’re all dealt with. Interestingly, this moment also evokes a lot of emotion. In spite of all of the unpleasantness the Bluths try to visit upon each other through the episode, Michael and Gob share a kind moment between brothers and the problems in the Fünke household are dealt with in some manner.

What Should We Steal?

- Populate your world with a full set of real people. You may not tell the reader what your tangential characters do in the future, but your reader should nonetheless be able to figure out some of the secrets that reside in their hearts.

- Allow your characters to be unlikeable…allow them to be human. Superheroes have been given increasing amounts of pathos for a reason. Real people are flawed; if you look deeply enough, there is darkness in us all. (Except for me.)

- Build your plots and subplots to a meaningful crescendo. No matter what you’re writing, think of yourself as a conductor. Your climax is the place where you detonate all of the land mines you’ve planted and when you get to show off your skills to the fullest.

Television Program

2004, Arrested Development, characterization, Hermano, Mitch Hurwitz, Teamocil

Even though Matt Nokes is my favorite player, the card is worth no more than a few cents. Certainly not enough to get Mike Ehrmantraut out of bed. And look at the card peeking out under Daniel’s left thumb. It’s a 1988 Topps football card:

Even though Matt Nokes is my favorite player, the card is worth no more than a few cents. Certainly not enough to get Mike Ehrmantraut out of bed. And look at the card peeking out under Daniel’s left thumb. It’s a 1988 Topps football card:

Here’s the problem. The production designer and the prop people and all of the other brilliant behind-the-scenes folks put together a show that makes me believe everything is real. I love being immersed into the seedy side of Albuquerque. These professionals even managed to find or make the perfect watch and shoes for Daniel’s character; the match the ugly paint scheme of the car and say a lot about his character.

Here’s the problem. The production designer and the prop people and all of the other brilliant behind-the-scenes folks put together a show that makes me believe everything is real. I love being immersed into the seedy side of Albuquerque. These professionals even managed to find or make the perfect watch and shoes for Daniel’s character; the match the ugly paint scheme of the car and say a lot about his character.