Title of Work and its Form: Sparky!, autobiography

Author: Sparky Anderson with Dan Ewald

Date of Work: 1990

Where the Work Can Be Found: I believe the book is out of print; you can find it at many of the fine secondhand bookstores around you or on the Internet. Mr. Ewald has written a few books about Mr. Anderson; Sparky and Me: My Friendship with Sparky Anderson and the Lessons He Shared About Baseball and Life was released in 2012.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Voice

Discussion:

As a lifelong Detroit Tiger fan, I grew up with Sparky Anderson and Alan Trammell and Lou Whitaker and Jack Morris and all of those guys. They were good—very good—in 1984 and broke my heart in 1987. (I don’t want to talk about what the team was like between 1995 and 2003.) Sparky Anderson was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2000, fitting recognition for his work as a major-league manager. Mr. Anderson reached the majors as a player, but knew that he wasn’t exactly good enough to make a life that way. He began managing the Reds in 1970, winning four pennants and 2 championships with the Big Red Machine. In 1979, he was removed as manager of the Cincinnati club and went to the American League’s Tigers. The 1984 Tigers started the season 35-5 and rolled to a Series victory over the Padres. (Sorry, Tony Gwynn.) Mr. Anderson ended his managerial career in 1995 at the age of 61. He died in 2010, having reached the top of his chosen profession.

Sparky reveals Mr. Anderson to be a very thoughtful man. The book begins with a confession: “My name is Sparky Anderson. And I’m a winaholic.” Mr. Anderson briefly describes his life and how it was influenced by his desire to win and then goes into detail about an interesting incident. The 1989 Tigers were 13-24 and Mr. Anderson had something of a panic attack/identity crisis. He went home to Thousand Oaks, California to take stock of his life. (Don’t we all have occasional dark winters of the soul?) After working out his problems, he returned to the Tigers, refreshed. What should writers steal from the first chunk of Sparky!? Mr. Anderson delves relatively deeply into issues of identity. He describes the difference between George and Sparky. Sparky was the fiery man who would yell at umpires and brood over losses; George was married to Carol and loved visiting children in the hospital.

The most striking part of the book (to my mind) is the voice that Mr. Anderson and Mr. Ewald employ. Mr. Anderson was certainly a very smart man, but he wasn’t the most formally educated man on the planet. You can flip to any page of Sparky! and find sentences with the same kind of diction. The sentences are short. The paragraphs add up to big ideas that could have been condensed into one sentence. Most of them begin with nouns or names. Here’s a representative section:

How does a person attain success?

Longevity. Because success is for the moment…and only that moment. So it must be aqcquired moment after moment after moment. That’s the difference and that’s where a lot of people make a mistake. In baseball, for instance, some guys think if they win one year that they’re automatically successful.

They’re wrong. That’s not success. All that happened was the blind squirrel happened to find an acorn. They could never repeat because they don’t have it in them. They were for the moment. But only for one single moment.

Mr. Ewald didn’t coax Mr. Anderson into longer, more complicated sentences. And that’s fine. Why? When I picked up the book, I wanted to feel as though I were spending an hour with George “Sparky” Anderson, a man with whom I’ve long felt a connection! Mr. Ewald traded the beauty of complicated diction for the simple poetry of authenticity.

I can’t help but interject with respect to a cause that means a great deal to me. Alan Trammell belongs in the Hall of Fame. Plain and simple. He was easily better than Ozzie Smith and Barry Larkin. Sparky agreed with me!

I’ve seen some great shortstops—Dave Concepcion, Ozzie Smith, and Cal Ripken, just to name a few.

I’d take Trammell because of everything he can do. Smith is a wizard in the field and can do more with the glove. Ripken is stronger and hits with more power. But Trammell does everything.

Trammell hits 15 homers a year, knocks in 90 runs a year and always plays around the .300 mark. In the field he never botches a routine play. People take that for granted, but that’s the sign of a great shortstop. If he gets a ground ball, it’s an out.

I’ve seen Trammell carry us in a pennant race after we lost a couple of key people like Lance Parrish and Kirk Gibson. That takes a special kind of player.

What Should We Steal?

- Confront the identity issues that are inherently wrapped up in your story. If you’re writing non-fiction, you’re writing about identity in some way. At the very least, you’re trying to take a person and paste them onto sheets of paper. What are the dilemmas that confront your characters, even if that character is you?

- Employ simple diction when appropriate. Mr. Anderson was brilliant, but he was no Gustave Flaubert. If Mr. Ewald had made Mr. Anderson sound like Shakespeare, the reader would not have such a visceral reaction to the book.

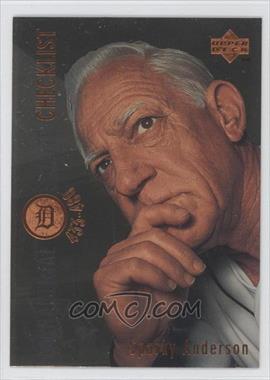

Sparky Anderson (1934 - 2010)

Sparky Anderson (1934 - 2010)