Writers are asked many general questions about their craft.

…”What is your overarching philosophy regarding the inherent power of fiction?”…”What IS-character-to you?”…”What is the position of place in your work?”…

These are great and important questions, but I’m really curious about the little things. In the “Hey, Why’d You Do That” series, I ask accomplished writers about some of the very small choices they made during the process of composition.

Katherine Riegel is a friendly woman and a good teacher. She’s also a co-editor at Sweet: A Literary Confection. Most of all, however, Ms. Riegel is a writer who loves creating poetry and creative nonfiction.

In November of 2014, Ms. Riegel published a powerful piece of creative nonfiction at Brevity. Go ahead; check out “Run Towards Each Other.” Then come back here and see why the author did what she did.

1) You begin “Run Towards Each Other” with the following two sentences:

“It is Thanksgiving, again. My smile is a weapon cutting off access to my grief-treasure.”

So…”grief-treasure” isn’t a real word. I even copied it into Microsoft Word to make sure. Then I looked on dictionary.com. Then I realized you must have made it up for some reason.

How did you decide to combine those two specific words? Why did you include the hyphen?

KR: Such an interesting question! I deliberately wanted to link those words in order to make sure the metaphor was clear. I imagined the smile/weapon protecting treasure—something precious, something coveted, something collected over time. So a stranger might see only the weapon, the defense—the smile. But the treasure being protected is actually grief. So it was layers of metaphor: smile=weapon, grief=treasure. In asking the reader to engage with complex metaphor, I didn’t want language itself to make understanding any more difficult. So I…bent language to make it do what I wanted. And I think the comparison of grief to treasure in particular is so unexpected, so out of the norm in terms of the ways we usually talk about grief, that I didn’t want the reader to be able to interpret it any other way.

2) The third paragraph is all one sentence. And there are en-dashes that split the sentence into three sections in addition to commas and everything else that makes up a sentence.

Why did you decide to combine all of those clauses? How did you make sure that the reader would know what you meant to say? What was the effect you hoped to create?

KR: Microsoft Word wasn’t happy with that sentence. (Though actually the 3rd paragraph is 2 two sentences, which itself is problematic because the 2nd “sentence” is technically two fragments separated by a dash.) In the first sentence of that paragraph, the dashes did what dashes are generally supposed to do, in that, if you took out the material inside the dash, the grammatical structure of the sentence, and its essential meaning, would be unaffected. Oh, and incidentally those were em dashes in my document; I think the formatting of the site turned them into en dashes. I wanted to put some description of my own smile into the piece, but I knew if I didn’t limit it that I could go on and on in the most unflattering ways about my own smile. This made it essential to keep the image short, tucked within a sentence. I also deliberately left out the “and” before “my new loves” because I wanted the three items in the list to be equal. Somehow adding “and” would make it feel like the last one, the “new loves,” was either more or less important than the other two. I intended the order to be more chronological than by importance.

I think also that this particular paragraph, reflecting my (the narrator’s) self after my mother’s death, is particularly fragmented. All the clauses, as you say, are both linked and separate, connected only tenuously through punctuation. The speaker, too, is just barely held together, and still doesn’t quite believe how or why she is. As for the 2nd sentence, where I get to write “me—me,” I confess I gave myself permission to do that because of some lines/line breaks in a Sharon Olds poem. It’s called “His Stillness” and the sentence reads like this:

At the

end of his life his life began

to wake in me.

She deliberately ended a line with a throwaway word—“the”—in order to get a line which begins with “end,” ends with “began,” and has “his life” repeated in the middle. I wasn’t breaking my mini-essay into lines (though I did when I first wrote it—shhh, don’t tell) but there was something really important about repeating that word “me.” The narrator doesn’t feel worthy of the support she’s gotten, so she must repeated the word “me” to persuade herself she matters, even as that words is followed by “insignificant.”

3) So, “toward” and “towards” are interchangeable, but “towards” has that extra Zzzzzzzzzzzz sound at the end. “Toward” has a nice, crisp consonanty ending.

Why did you use “towards?”

KR: I have to confess this may be just dialect. I grew up in Illinois with parents from DC and Pennsylvania who went to school in Vermont. When I take “accent quizzes,” it nearly always gets my accent wrong because of that. (I say “ca-ra-mel,” for example, not “car-mel.”) I guess, when I think about it, “towards” sounds more together-y to me. People are running towards each other—everyone is doing the action. A person would run toward a house, because the house wouldn’t be doing the action. Or maybe I’m completely full of it, and I’m a teacher, so I can come up with an answer even if I have to make it up. 🙂

4) I’m pretty sure Grammar Girl would tell you that you didn’t need that comma in the sentence, “It is Thanksgiving, again.”

How come you put that comma there?

RM: Oh, yes. Very important, and very deliberate. I wanted to emphasize “again.” It is inevitable, it keeps coming around even when you don’t want it to. Putting the comma there was to try to show the dread, to make the reader feel just how much the narrator didn’t want it to be Thanksgiving—again. Oh boy. Here we go.

5) And here’s the penultimate sentence:

“In the barn I will pull carrots out of my pockets and hold them flat on my palms.”

“In the barn” is a dependent clause that begins a sentence. All of those nerds who complain about grammar stuff might say that you shoulda put a comma after “In the barn.”What made you leave the comma out?

KR: Really interesting punctuation questions! I think language has a music to it, a rhythm. Grammar and punctuation rules are in place to help with clarity, but we all know many of them are arbitrary and some are based on the rules of Latin, which early English grammarians decided was the only “proper” language and so must be imitated. In this case, it’s clear what’s happening, and I heard the sentence in a particular way in my head. It wasn’t interrupted by a pause after “barn.” I’m one of those people who hears a voice very clearly in my head when I read; I don’t read my work aloud much during revision because it’s redundant. I heard this sentence as a whole, the image words like fence posts, regularly spaced: barn, carrots, pockets, flat, palms.

It’s odd to see how often I bend/break grammar and punctuation rules, when I emphasize clarity in both those areas as a teacher. I suppose I’m more concerned with syntax and its possibilities than with absolute rules. I want writing to be precise, in order to get across nuance and subtlety. That kind of precision requires a writer to make considered choices that sometimes break rules.

Katherine Riegel is the author of two books of poetry, What the Mouth Was Made For and Castaway. Her poems and essays have appeared in journals including Brevity, Crazyhorse, and The Rumpus. She is co-founder and poetry editor of Sweet: A Literary Confection, and teaches at the University of South Florida. Visit her at www.katherineriegel.com.

Creative Nonfiction

2014, Brevity, Katherine Riegel, Sweet: A Literary Confection, Why'd You Do That?

Title of Work and its Form: “Stitching the Womb,” creative nonfiction

Author: Pamela Ramos Langley

Date of Work: 2014

Where the Work Can Be Found: The piece made its debut in Hippocampus Magazine and can be found right here.

Bonuses: Here is Ms. Langley’s Pinterest feed. Here is a short story Ms. Langley published in The Story Shack. Here is some more fiction that Ms. Langley placed in Drunk Monkeys.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Brevity

Discussion:

The piece begins as Ms. Langley is undergoing infertility treatments. The kind nurse in the gynecologist’s office gives her good news: her hormone levels are high and she may be pregnant. By the end of the vignette, reality sets in and Ms. Langley suffers a miscarriage while driving a rental car. The rest of the piece centers upon the emotions that surround the author and her friends in relation to pregnancy and parenthood. A friend who is also having difficulties getting pregnant laments that some women have children, even though they really don’t “deserve” them. In a sweet vignette, Ms. Langley spends time with Jenna, a little girl whose single mother spends some of her time clubbing. The last of the seven sections finds Ms. Langley spending $650 for a telephone session with a psychic healer. There is no happy ending; Ms. Langley ends the piece in the same state of limbo in which she began it.

Ms. Langley chooses a felicitous structure for the piece. There are plenty of narratives out there in which men and women discuss their problems conceiving children. Instead of opting for a chronological recap of the medical ins and outs of infertility, she instead chooses to zoom in on seven moments that mean something important in her journey to become a parent. (And what powerful moments they are!) Condensing the narrative allows author and reader to get past the mundane parts of this kind of story. When we’re reading creative nonfiction, we really don’t want to know the general feelings of a person who deeply wants a child; we want the specific experiences and feelings of an author. I’m guessing that many men and women who have these kinds of problems find themselves in a park talking to a parent whose child is running around; Ms. Langley omits the exposition we could probably supply for ourselves and makes the shrewd choice of casting the scene in a single paragraph that is told very much from her standpoint. In this way, the focus remains on Ms. Langley’s experience.

While I’m very sad that she had the experience in the first place, I love the way Ms. Langley describes the miscarriage. Instead of TELLING us what happened, she SHOWED us. Even a childless bachelor such as myself can figure out what it means that a pregnant woman with a history of fertility problems experiences “vicious” cramps. Ms. Langley uses imagery to serve as description; the “lurid red stain” on the front seat of the rental car punches us in the gut and we appreciate being treated like adults who paid attention in ninth-grade Health class.

I’m not sure who chose the image that accompanies the story on the Hippocampus web site, but the image of the broken egg upon the sand is as powerful as it is simple. The title of the piece gives you the idea that you’ll be reading about something related to pregnancy; the smashed egg prepares you for the unhappiness that runs through Ms. Langley’s account. What’s the lesson? If you’re an editor, simple images can have a big effect on the perception of the work you’re curating. If you’re the author, perhaps you make a polite suggestion to the editor as to what kind of photograph should be coupled with your work.

What Should We Steal?

- Omit needless scenes and description. We all remember what the first day of school was like. What made YOUR first day of school special? We’ve all experienced the grief of losing a loved one. How does YOUR grief manifest itself in a unique and meaningful manner?

- Avoid strict definitions of what is happening when the reader can figure it out for themselves. Remember “The Contest,” the Seinfeld episode in which the four main characters decided to see who could resist masturbating the longest? None of the characters actually uses the word, “masturbation” or any of its variants. While I’m guessing the restriction was a Standards and Practices thing, the episode is all the better because the characters were treating us like grownups. What else could it mean when George laments that his mother caught him when he was “alone” with a Glamour magazine?

- Contrast emotionally powerful and complicated work with simple illustrations. It’s really not necessary to tell people they should be sad when they read about a person who wants a child, but can’t have one. Showing the reader an unopened crib in a half-painted nursery can be much more powerful.

Creative Nonfiction

2014, Brevity, Hippocampus Magazine, Pamela Ramos Langley, Pregnancy

Title of Work and its Form: The Accidental Buddhist: Mindfulness, Enlightenment, and Sitting Still, creative nonfiction

Author: Dinty W. Moore

Date of Work: 1997

Where the Work Can Be Found: The book can be purchased at fine bookstores everywhere. You can also purchase the e-book version of The Accidental Buddhist. (Also available on the Nook, a device with far less onerous DRM.)

Bonuses: Mr. Moore is the editor of Brevity, a very cool online journal of creative nonfiction. All of the pieces in Brevity are, appropriately, somewhat brief. Here is an interview Mr. Moore did with Bookslut. Here is a brief taste of a Skype-type interview Mr. Moore did for Author Feast:

The whole interview can be viewed on the Author Feast web site.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Point of Entry

Discussion:

American lives have sped up a great deal in the past century. Our breathless days seem, as Mr. Moore points out with statistics, more complicated than they did even a few decades ago. How utterly appropriate then, that Buddhism might appeal to an increasing number of Americans. The Accidental Buddhist is…

- An account of what happened when Mr. Moore immersed himself in the world of American Buddhism. Mr. Moore visits several monasteries and has conversations with many Buddhists, trying to open his mind to the philosophy.

- A work of autobiography that offers great insight into Mr. Moore’s way of thinking. (In 1997, at least.)

Through the course of the book, Mr. Moore creates his own very modern American koan and sees Steven Seagal and the Dalai Lama. He ends up at Comiskey Park and reflects upon the Buddhist inclinations of baseball. Most of all, Mr. Moore undertakes a journey for understanding and enlightenment, which seems very Buddhist indeed.

Speaking of Steven Seagal, doesn’t “point of entry” sound like one of his films? Mr. Moore chooses a powerful point of entry to the story of his exploration of Buddhism. After a brief prelude, Mr. Moore offers “Buddha 101,” a chapter in which he describes his own entry into a Buddhist retreat in the Catskills. Mr. Moore adjusts to sitting on pillows and trying to keep his mind clear, no matter how difficult that sounds. Mr. Moore is learning the Buddhist terms in the narrative, which makes it easy for him to teach the reader, for example, what a koan is. The reader’s point of entry aligns with the author’s in this case.

Instead of presenting himself as an authority at the beginning of the book, Mr. Moore explicitly orients himself as a man who is simply embarking on a journey. The reader feels a sense of comfort and is united with the author because of this positioning. Consider a work of art with the exact opposite arrangement. The point of entry for Full Metal Jacket is the moment when the men are having their heads shaved at the beginning of boot camp. Immediately thereafter, Gunnery Sergeant Hartman shows up:

Sergeant Hartman is EXPRESSLY positioned as an expert and an authority and the men are VERY CLEARLY subordinate to them. In The Accidental Buddhist, we feel as though Mr. Moore has offered us a ride to the monastery just down the road. In Full Metal Jacket, the viewer likely feels the same fear and discomfort that the men feel. (Especially Private Pyle.)

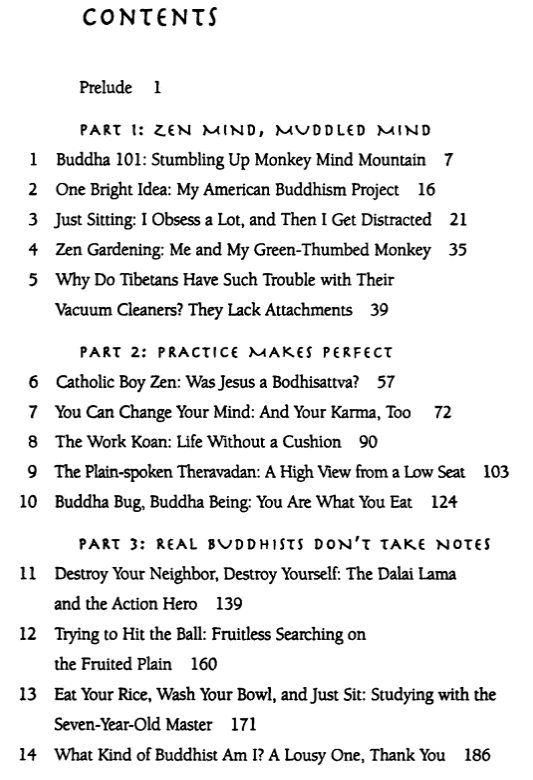

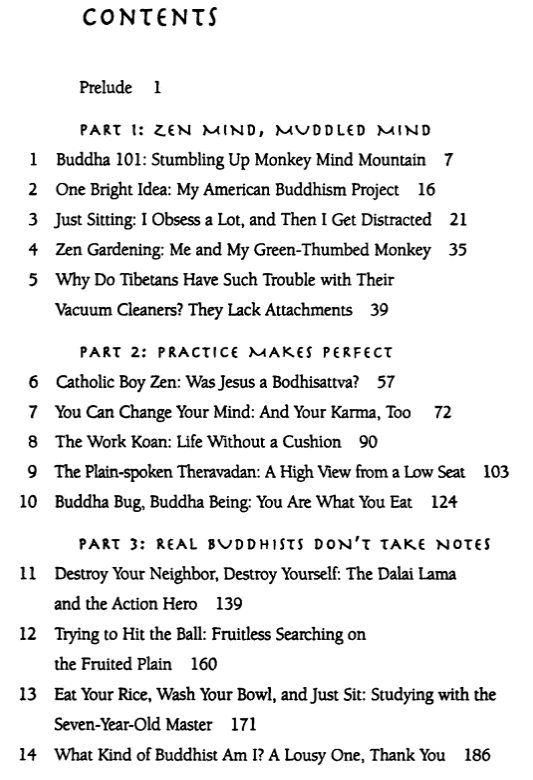

I love the titles that Mr. Moore chose for his chapters. Check out the table of contents:

I think it’s fair to say that Buddhists and writers both try to think about the choices they make and the effect they have on others. What do these chapter titles tell us about the book or about Mr. Moore?

- The book will explore a number of religions in comparison with one another.

- “Sitting,” “obsessed,” “distracted,” “lousy;” the author is self-deprecating and honest.

- The use of a few Buddhist terms indicates that Mr. Moore will offer definitions and has a sincere interest in exploring the issues.

- The titles are as fun as they are verbose. The author is, no doubt, a compelling conversation partner. (I love that the title of Chapter 5 is literally a joke.)

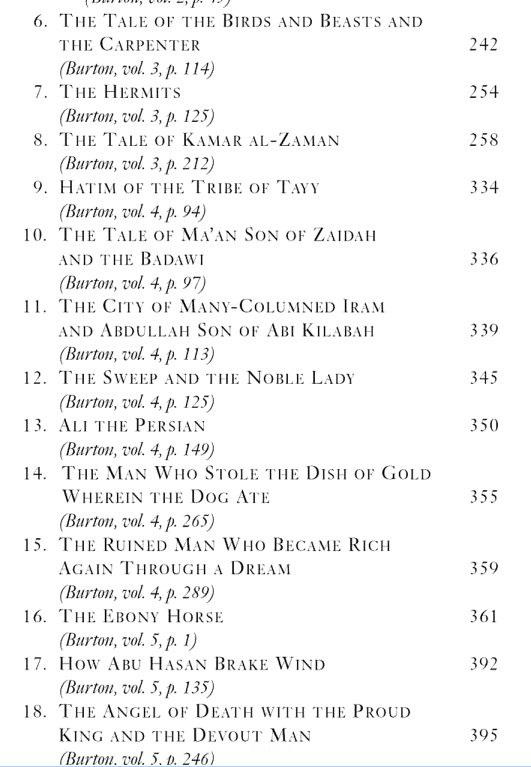

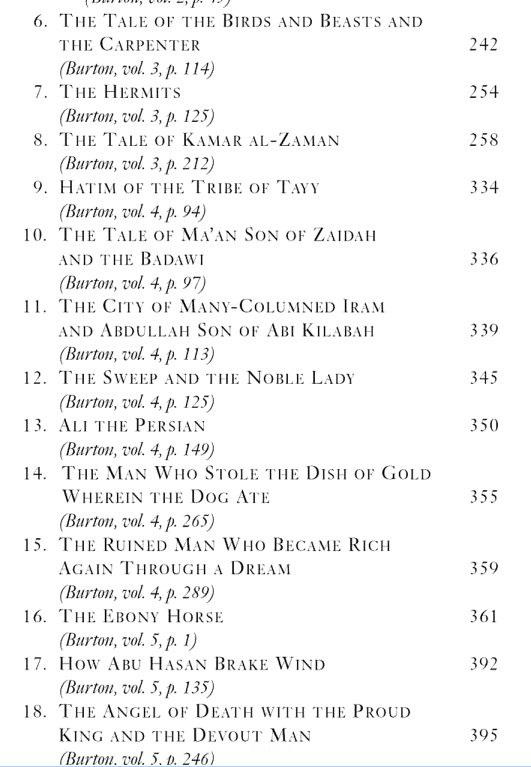

Compare this table of contents to that of a recent edition of 1001 Nights, one of the most entertaining books EVER.

The book’s frame story itself grabs your attention. The King is angry at a woman who betrayed him, so he’s bedding and beheading a woman a night to get revenge. Scheherazade volunteers; she has a plan. She begins telling a story on the first night and the tale is so compelling that the King lets her live. SPOILER ALERT: there are 1000 more nights. See how the conceit alone lets you know how cool and fun and brutal and primal these stories are? Do the chapter titles communicate any of that fun? “The Ebony Horse.” “Ali the Persian.” These are descriptive, but offer little else to the reader. Mr. Moore, on the other hand, allows the table of contents to reflect the tone of the work as a whole.

What Should We Steal?

- Consider how the point of entry into your story will affect your reader. Does the start of your piece alienate people or invite them to join you? Which do you intend?

- Craft chapter and section titles that reflect the tone of your work. Yes, it means more work for us, but it’s our job as writers to create the best “work” we can, no matter the form.

Creative Nonfiction

1997, Brevity, Dinty W. Moore, Point of Entry

Title of Work and its Form: “Letter to a Future Lover,” creative nonfiction

Author: Ander Monson (On Twitter: @angermonsoon)

Date of Work: 2012

Where the Work Can Be Found: The piece was published in Spring 2012’s Issue 39 of Brevity, a very cool online journal of short creative nonfiction. Check out the “Letter to a Future Lover” right here.

Bonuses: Wow…the New York Times Sunday Book Review really likes Mr. Monson! Perhaps you would like to visit DIAGRAM, the literary journal Mr. Monson edits.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Material

Discussion:

Mr. Monson bought a copy of Gary Snyder’s Turtle Island in a thrift shop and found a three-page inscription in the volume. (In case you’re curious, the book won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1974.) One lover wrote to someone he or she has lost, lamenting the dissolution of a special relationship. The experience led Mr. Monson to consider the real nature of our legacies to others: “A codex is a door…Codices have histories.” Just like the lover who inscribed the book, we’re all simultaneously an open book to those who we love and a method of transformation that changes them into something new.

What is writing but an attempt to understand our own lives in the context of those of others? It would be easy to look at a long inscription in a book and simply ignore it and to go about your day. Instead, Mr. Monson demonstrates that he lives the true life of a writer: he sought to understand the person who wrote in the book and tried to understand his own life in the context of someone else’s bare emotion.

Mr. Monson wrote a beautiful little essay because seeing the inscription inspired him to address a future lover in hopes of avoiding the problems encountered by the inscriber. Mr. Monson stole the events of someone else’s life and created a creative work out of them. You can do this, too! Check out the site Post Secret. Folks around the world create a postcard that confesses a secret they would otherwise never share with the world. One parent confesses how hard it is to care for an autistic child. That’s pretty harsh, isn’t it? It’s also HONEST, in the way our own writing should be. What is it like to be the father? The autistic child? Is he a single father? What will happen in the future? There are so many “what if”s and you can steal this man’s confession and turn it into your own fiction.

Another depicts a bobby pin on a night stand with the text: “I left a bobbypin on your nightstand on purpose, so she would see it.” Crazy, right? You could tell the story of the “other woman,” you could tell the story from the wife’s perspective. You could also follow Mr. Monson’s example and simply strip your emotions bare and write a nonfiction piece in which you consider the nature of monogamy and the strength of the vows that bind us.

The piece appeared in Brevity, a nonfiction journal dedicated to evoking great meaning in as little page (or screen) space as possible. Mr. Monson makes every word count and is still playing with very big ideas.

What Should We Steal?

- Consider the meaning of the small and strange experiences that happen to you. The fateful connections that touch our lives make us part of the tapestry of humanity. Revel in these coincidences.

- Appropriate the real-life stories you find as you explore the world. Any time you hear a crazy real-life story, feel free to steal any of the elements you like.

- State your point quickly. Brevity is the soul of wit. (I thought of that.)

Creative Nonfiction

2012, Ander Monson, Brevity