Title of Work and its Form: “The Atheist of Dekalb Street,” short story

Author: Christopher DeWan (on Twitter @theurbansherpa)

Date of Work: 2013

Where the Work Can Be Found: The short story made its debut in Wigleaf, a cool journal of [very] short fiction. You can find the story here.

Bonuses: Mr. DeWan did an awful lot of writing for his now-defunct blog The Urban Sherpa. Here is an interview Mr. DeWan did for LitWrap. “An American Dream” was published in Necessary Fiction.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Description

Discussion:

This short story is told from the first person perspective of a boy who spends time with an old woman who (he believes) is the only atheist in a neighborhood filled with Catholics. There are rumors that the woman has stigmata, and she does indeed have some sort of wounds on her hands. The woman seems to be in failing heath. The boy cares for her and anoints her with tap water (the atheist kind) and comes to the epiphany that something is only holy or special if we believe it is.

Mr. DeWan introduces the atheist’s “stigmata” early in the short story, after making it clear that he lives in a very religious (and very Catholic) community. When a woman-who also apparently happens not to be a member of the faith and is not even a Protestant-develops wounds in her palms and feet, the narrator can’t help but believe that they are stigmata. When Mr. DeWan brings such a concept into the story, we have a decision to make. Is this a piece of magical realism? Are the stigmata fantastic in some way? Or are these regular old wounds that have been given weight by the narrator and his religious background?

It’s my impression that Mr. DeWan is working in straight-up realism and that the holes in the woman’s hands got there by conventional means. The narrator’s description, however, serves as great description. Mr. DeWan doesn’t need to devote much time to bare description of the stigmata because we already know what they look like based upon what the narrator thinks they are. The author is making felicitous use of the different levels of understanding possessed by character and reader. We do this same kind of thing with children. If a child says they heard a “big boom” outside, we make a leap or two and understand that they mean they heard a thunderclap. Mr. DeWan’s use of this technique adds to the efficiency of the piece; he gains both characterization and exposition.

Mythologies have had a strong hold on the human imagination for a very long time, and for good reason. Myths explain the unexplainable and help us orient ourselves with respect to the rest of humanity. The story ends as the narrator “baptizes” the atheist of Dekalb Street with tap water. The boy hopes that this action will wash the woman’s soul clean, ushering her into a state of divine blessing. The baptism means something else in purely secular terms. The woman is near death and her body is breaking down. Doesn’t it make perfect sense that the story should end with a young person anointing an elder who is about to pass into that undiscovered country?

This story is imbued with Catholic mythology by virtue of its narrator. I love the double meaning possessed by the final move in the story. It makes sense that a young boy will think of baptizing a stranger. The narrator is not as likely to think of another Catholic sacrament: the anointing of the sick (the last rites). Mr. DeWan builds power and relatability into the story by aligning it with stories that hold powerful sway over so many.

What Should We Steal?

- Make use of the differences between your protagonist and your reader. The man or woman holding your book will likely have deeper understanding of the world than that of some of your characters. Allow your reader to process information on behalf of characters who can’t.

- Commemorate the growth of your characters with the same sacraments found in mythology. Fiction is all about characters who reach new levels of understanding and consciousness and who become something new. Aren’t these aims similar to those of religion? A young woman is considered an adult after her bat mitzvah. A Muslim fulfills a lifetime goal by making their way to Mecca for the Hajj.

Short Story

2013, Christpher DeWan, Description, Wigleaf

Title of Work and its Form: Buffalo Soldiers, novel

Author: Robert O’Connor

Date of Work: 1992

Where the Work Can Be Found: The book was published by Vintage and can be purchased at all fine local bookstores, including Oswego, New York’s River’s End Bookstore. Or from Amazon. Or Powell’s. Just buy it.

Bonuses: Why not check out the New York Times review of the book? The novel was also adapted into a film starring Ed Harris and Joaquin Phoenix. Here’s the trailer.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Description

Discussion:

Specialist Ray Elwood is an Army man stationed in Germany, but he’s not the kind of soldier you see in the recruiting posters. Elwood uses and sells drugs and works in Colonel Berman’s office, writing letters and helping the colonel write scholarly articles about the art of war. You have to grease a lot of palms and out-think a lot of people if you’re in Elwood’s line of business, and he’s always a step ahead. Even when a new Top arrives. Sergeant Lee doesn’t like Elwood very much; as a former drug user, he can see right through Elwood’s façade. Sergeant Lee also has a beautiful young daughter, Robyn, who has lost most of an arm for reasons I won’t divulge. As you might expect, Elwood’s situation deteriorates through the novel and Elwood has new and greater dragons to slay. The first three-quarters of the book is a page turner; the last quarter is a breathless race to an inevitable conclusion. Re-reading this summary, you might not realize the book is a dark and powerful comedy that is grounded in real human emotion.

Mr. O’Connor happened to be one of my teachers at Oswego State. (To my great honor, he’s currently one of my colleagues in the Creative Writing Department.) One of the many reasons he’s a strong teacher is that he offers customized advice to each student in the service of honoring the student’s literary goals above all. This is a policy that was also held by my great teachers at Ohio State, and a goal I have today in my own teaching. You want to write an experimental thriller starring an anthropomorphic stapler? That is not at all the style of fiction that I personally enjoy, but great. Let’s make this the best killer stapler story we can. You have a sentimental and sincere love story in mind? That’s not my bag, but what can we do to make this the sweetest and least complicated love story possible.

I have no idea how many students do what I did each time I had a new writing teacher: I got one of his or her books or read some of his or her stories. (Or plays.) You may not wish to write a book like Buffalo Soldiers, for example, but you can tell immediately that Mr. O’Connor is a master of description and excellent at maintaining narrative momentum. Understanding his work allows you to ask more specific questions and to interact in a more meaningful manner. It’s also a lot of fun to talk to writers about their work. I remember having a question about one of Erin McGraw’s sentences when I read it…as her student, I was welcome to e-mail her and ask her specific questions about her craft! (Most writing teachers love talking to students, don’cha know.) Think about it in another, less scholarly way. Can it really hurt you if your teacher sees you walking around with a copy of his or her book? (Especially if it’s not from the library!)

Okay. Let’s get to the lessons you can steal specifically from Buffalo Soldiers and not just its author. I have to acknowledge the elephant in the critical room. Many folks have heaped laurels upon Mr. O’Connor because of the way he used the second person in his book. (I may be wrong, but it seems as though this point of view has been used more since the Buffalo Soldiers/Bright Lights, Big City era.)

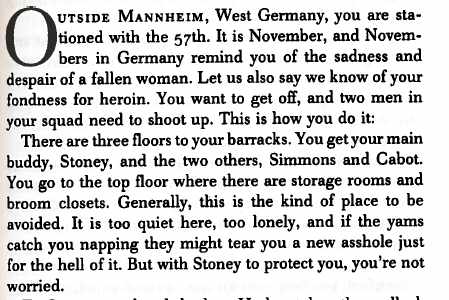

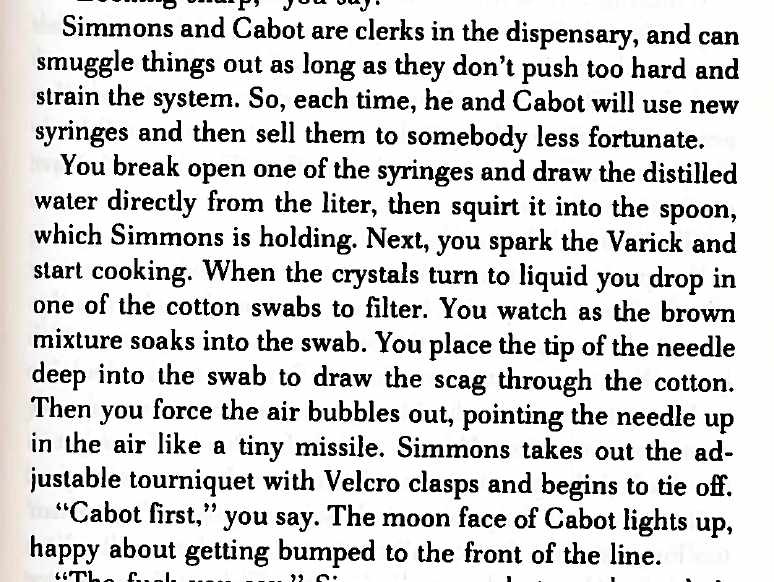

One of the primary advantages of a second-person POV is that you’re explicitly forcing the reader into sympathizing with your character. Check out the very beginning of the book:

Mr. O’Connor accomplishes a lot with the first two paragraphs:

- The first sentence establishes the second person POV.

- You learn that Ray Elwood (the protagonist) is in the military and is stationed in Germany.

- You learn that Ray is not exactly a happy man.

- You find out that Ray enjoys heroin and is the leader when it comes to helping others use the drug.

- You discover that Stoney is the muscle in the group.

- It’s immediately clear that Ray likes to break the rules and knows how to work around them.

So Mr. O’Connor does indeed help you relate to Ray with the use of the second person POV. More importantly, the POV creates a more visceral understanding of some “extreme” actions. How many of us know what it’s like to cook and shoot heroin? When you read the book, “you” do. I’m wagering that few folks who read this know what it’s like to patronize a German brothel. Well, through the use of the second person, “you” do. The decreased narrative distance between the reader and Ray helps bridge the gap between them and makes some dangerous and exotic plot developments seem a lot more normal. If the book were in the first person, some readers may have been more judgmental of Ray’s actions as Ray tried to explain himself to the reader. In the third-person, the narrator may have seemed very far away from a character who, on some level, just wants others to understand him.

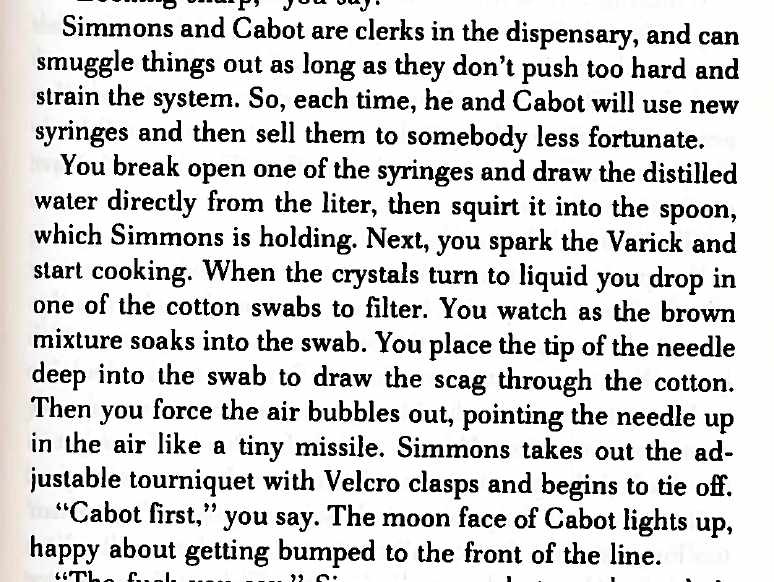

Mr. O’Connor also provides a master class in description. I hate needles…the narration of the drug use scenes made me just as uncomfortable as if I were in a doctor’s office to get a tetanus booster. One of the characters decides to get circumcised; the description made me shift in my chair as I read. Look at the way Mr. O’Connor describes the cooking of heroin, a procedure with which many readers may be unfamiliar:

His sentences are short and relatively simple. There are plenty of complicated and beautiful sentences in the book, but Mr. O’Connor doesn’t employ them here. Mr. O’Connor wows you with his ability to make music with words, but ensures that he is very clear as to what a heroin user does with the cotton balls.

I won’t spoil the ending, but it’s stellar. It’s no surprise that Ray gets himself into some big trouble. Mr. O’Connor sticks the landing, so to speak. The ending addresses all of the conflicts that he has introduced during the course of the book. In the space of a few pages, all of the book’s questions are resolved. Even better, the promise of the character of Ray Elwood is fulfilled.

What Should We Steal?

- Read the work that has been produced by your teachers and be open to all kinds of mentors. On one hand, it may be great for a pure mystery writer to work closely with a teacher who only writes mysteries. On the other hand, lots of great teachers work, teach and/or write in all genres and their primary goal is to help you with your specific story.

- Employ second person to help your reader feel experiences that are alien to them. The second person knocks down some of the barriers between the reader and characters who may be engaged in unusual or unexpected activities.

- Provide lush and simple descriptions for exotic actions. Your reader may not know what it’s like to speed down the Autobahn or to take a tank for a joyride. Ensure that you describe such actions in simple and powerful terms. (You know…if you have access to a tank, I would love to find out what it’s like to go for a joyride in the first person.)

- Concoct a conclusion that connects all of the questions you’ve contrived. The ending of a novel (or a song or short story or nonfiction piece) is like the blossoming of a flower. You have planted and pruned and fertilized…now it’s time to enjoy the logical end of all of your labor.

Novel

1992, Description, Oswego State, Robert O'Connor, Second Person

Title of Work and its Form: “Honors Track,” short story

Author: Molly Patterson

Date of Work: 2012

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story debuted in the June 2012 issue of The Atlantic. I’m sure you’ll be able to find it in future best-of anthologies in addition to a future Molly Patterson short story collection.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Description

Discussion:

Molly Patterson tells the tale of a group of highly driven high school students who are determined to succeed at any cost. These are the alpha student, Tracy Flick types who sweat over every fraction of every GPA point. The group decides to begin cheating on exams, adding the fear of being caught to their vast list of stressors. I hate to ruin an ending, so I won’t. (Particularly because I plan on discussing the beginning of the story. I will say that Patterson makes some interesting choices and that the ending is worthy of further scrutiny.)

Check out the first few lines of the story:

We were sedulous. We were driven. Our vocabularies were formidable and constantly expanding. We knew the chemical elements by number and properties, the names and dates of battles in the world’s greatest wars.

I can’t recall the last time I saw the word “sedulous” and I was pleasantly surprised to see it at the very beginning of a story. (Sedulous means “diligent” and “persistent,” by the way.) Is this a bad thing? A lot of beginning writers, myself included, used big words because, well, it sounded like something a WRITER would say. Shouldn’t a writer be scared about turning the reader off by using a word that may not be understood by “the woman on the bus?” In this case, no. And here’s why: “Sedulous” is not a very commonly used word, but it does sound like an SAT word, the kind of word that Patterson’s characters obsessed over for hours. In the very first sentence, she tells you a whole lot about this group of acquaintances. Not only were they sedulous, but they were very smart and they didn’t hide it. This extreme dedication and extreme intelligence are the primary qualities that led them down the path they chose in the story.

Patterson’s opening paragraph also eases us back into the high school mindset. When was the last time you thought about the chemical elements and their properties? High school. (Hmm…I remember Mr. Powell telling me all about valence electrons.) When did we last learn about the world’s greatest wars? High school. (Mr. Magnarelli taught us all about Chamberlain’s appeasement before World War II.) Perhaps it’s just me, but I don’t often think about high school; Patterson punches a few buttons that accesses those memories, bringing me closer to the characters.

What Should We Steal?:

- Understand the potential power that a single word can possess. The opening sentence would probably not have attracted my attention had it read, “We were diligent and persistent.” Yes, it is easy to alienate the reader by using “big” words, but a writer must not talk down to his or her audience. Instead, the writer must use the word that is RIGHT.

- Use subtle references to gracefully immerse a reader in a setting that is unfamiliar. Think about the experiences most of us share. Most of us remember liking a guy or girl who didn’t like us back…we remember taking our road test…we remember times when our parents were disappointed in us. Small details relating to those experiences can be extremely potent.

Short Story

2012, Description, Molly Patterson, Ohio State, The Atlantic

Title of Work and its Form: “A & P,” short story

Author: John Updike

Date of Work: 1961

Where the Work Can Be Found: The short story is frequently anthologized and can be found in countless collections of American short stories.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Description

Discussion:

When most people think about twentieth-century American literature, they think Honey Boo Boo. (Unfortunately, that program is neither from the twentieth century, nor is it literature.) John Updike comes a very close second. The man was one of our literary lions for a half-century and deserves his due. “A & P” is a tight little story about a young man who works in a grocery store. He’s nineteen years old, so he definitely notices when “these three girls” walk in wearing “nothing but bathing suits.” The young ladies make their way around the store and finally approach Sammy (the first-person narrator), who is working the register. Unfortunately, the boss breaks the spell and ruins everything, telling the young ladies that they should dress “decently” when shopping in his store. Sammy mutters that he quits and realizes “how hard the world was going to be” to him thereafter.

A lot of writers fight over how much they should describe their characters physically. Unfortunately, the answer is not an easy one: writers should provide as much description as is necessary to serve the story. It doesn’t matter what color her hair is, but it matters very deeply to Sammy that the young woman he calls “Queenie” is wearing a “kind of dirty-pink—beige, maybe, I don’t know—bathing suit with a little nubble all over it.” The suit’s straps are down, “off her shoulders looped loose around the cool tops of her arms…” Updike chooses the details that would be noticed by the narrator. You better believe that a heterosexual nineteen-year-old male is going to notice the “clean bare plane of the top of her chest down from the shoulder bones like a dented sheet of metal tilted in the light.”

Coming up with names and getting them into a narrative can also be a problem at times. How often do you walk around and hear someone’s name unless there’s a really good reason? If you go to someone else’s family reunion, you’re going to hear an awful lot of organic introductions. “Jim, have you met my Uncle Bob? He’s married to my Aunt Sally.” In many narratives, however, these opportunities may not be easy to come by. That’s why Updike (through his narrator) simply calls the primary young woman “Queenie.” Not only does the name reflect what Sammy thinks about the young woman, but it also shapes our understanding of the character. After all, haven’t we all identified the leader of a group and focused on them?

What Should We Steal?

- Include character details that actually matter. Your reader is going to fill in a lot of the blanks, so include the specifics that shape your narrative or characters. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing. What does it matter if your reader imagines that one of your characters appears African-American or Armenian or Argentinian? In this case, the racial appearance of the character will only matter if it is important to the story. Shakespeare only describes Othello as a Moor because…well…it’s the whole point of the play.

- Dole out character names in a felicitous fashion. Imagine you have a character walking through a dark, dank parking lot. What should you call the man who is following him or her in a menacing fashion? Well, you could call him “the man” or “the creep” or “Scary Jerk.” Each identifier will shape the audience’s perception of your story, so choose wisely!

Short Story

1961, Classic, Description, John Updike

Title of Work and its Form: The End of Everything, novel

Author: Megan Abbott

Date of Work: 2011

Where the Work Can Be Found: At fine independent booksellers anywhere. Fine. Okay. The book can also be purchased on Amazon.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Description

Discussion:

Edgar Award-winning author Megan Abbott’s first novels are pulp fiction tomes that somehow capture the flavor of a time that passed decades before she was born. Her work is evolving in very interesting ways; this book certainly can’t be called a pulp novel and is not as much of a crime/thriller as it is simply a literary coming-of-age story. The first-person narrator of the book is thirteen-year-old Lizzie, a young woman who is lucky enough to have a friend like Evie Verver. The two grew up together and shared everything. Well, not everything. (There would be no book otherwise.) In very short order, Evie has been kidnapped by Harold Shaw, an insurance salesman who has a family of his own. Appropriately, Lizzie is the driving force behind the investigation that brings Evie home and learns an awful lot about herself, the Ververs and life itself.

Ms. Abbott took on a number of challenges by putting Lizzie in control. Although Lizzie-in-the-first-chapter is looking back on the book’s events with the wisdom granted by the passage of time, the rest of the book is told from the perspective of a very young woman who is still unversed in the ways of the world. On one hand, Lizzie cannot figure everything out too easily; on the other, Lizzie must be able to navigate the mysteries confronting her. Ms. Abbott makes the wise choice to simply trust her narrator and to give her the time she needs to realistically work through her many problems.

One technique Ms. Abbott used to create this kind of successful narrator was to vary the length of her sentences and amount of psychological insight contained within. Here’s the opening of third chapter:

The phone rings. It’s ten thirty at night. I’m brushing my teeth when it happens, and I hope it’s not my dad calling from California, calling from his apartment balcony, a sway in his voice, talking about the time we rented canoes at Old Pine Lake, or the time he built the swing set in the backyard, or other things I don’t really remember but that he does, always, when he’s had a second glass of wine.

The concrete details are contained in punchier sentences. Okay, so the phone rang when it was a little late. Not much analysis needed on Lizzie’s part, right? That long third sentence, however, does a great deal of work. The reader learns:

- Lizzie has some unresolved problems with her father

- The father feels some measure of regret for their current situation

- Lizzie remembers many of the good things he did

- Lizzie understands that these memories are often evoked by an extra drink

When all of the “raw data” is put together, the reader gains a deeper understanding of what Lizzie and her father mean to each other. This process also mimics the process by which we all mature; we absorb data, think about emotions and boom: we gain a little pearl of wisdom at some point. We can truly call ourselves adults when we have enough of those pearls. (I’m about three dozen short at the moment.)

People don’t arrive at epiphanies easily in real life and neither should Lizzie. Look at a some of Lizzie’s thoughts that arrive approximately three quarters through the book. (Don’t worry; it doesn’t really give much away.)

They’d been there, been there behind one of those clotty red doors, and done such things…and now gone. And now gone. And every night they stayed there when he left to get her food, did he lock her in – did he lock her in? How could he? But he would leave there and she would be there and would she wait, reader for her dinner, ready for him to click open the door and provide her with her dinner, like a jailer with no keys, with no locks, with no prisoner at all.

The first few sentences remind me of a gymnast working through his or her moves before a routine. The gymnast takes a step or two, twirls his or her arms and legs about a little and runs through the routine mentally. That last sentence? The gymnast (Lizzie’s thought) is off and running and nothing can get in the way. Narration such as this unites narrator and reader; both are trying to understand what is happening in the story and in the hearts of the characters living it. (Even better, the sentences are beautiful and musical and maintain dramatic momentum.)

What Should We Steal?

- Match your character’s lines and thoughts to his or her maturity level or mental state. Nineteen of the twenty chapters in The End of Everything are written from the perspective of a relatively bright thirteen-year-old woman. Ms. Abbott makes sure Lizzie always sounds and thinks like one. Lizzie asks a million questions as she tries to fill in her understanding of the world and of love and is even somewhat cryptic when relating information a young lady may not want to talk about…

- Construct your piece in a manner that serves the story you wish to tell. In different hands, The End of Everything would have been a far different book. While Ms. Abbott is very good at describing the “mystery/crime” elements, she devotes far more time to telling Lizzie’s story against the backdrop of the novel’s events. You have to decide which is most interesting to you: the explosion or its aftermath.

Novel

2011, Description, First-Person Narrator, Megan Abbott, Novel, The End of Everything

Title of Work and its Form: Home is the Sailor, novel

Author: Day Keene

Date of Work: 1952

Where the Work Can Be Found: The book was republished by Hard Case Crime in 2005. You can also purchase vintage copies at fine secondhand booksellers.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Description

Discussion:

It’s hard to find books that are more exciting than those in the pulp fiction genre. These books are how people got their Law & Order fix before there was Law & Order. The deliciously lurid covers attract attention—an oil painting of a dangerous woman in love-rumpled clothes beckons you—and the characters and situations fulfill our primal need to experience crime and passion. Day Keene was a pulp writer who also wrote suspense radio shows. (You should check those out, too!) Home is the Sailor only takes place over a few days, but those days are very busy! Swede is a sailor just home from a long stretch at sea. He has $18,000 in his pocket and wants to go home to Montana and buy a farm and plant some roots. Unfortunately, he met Corliss, the owner of a tourist stop. Before long, he’s in love. Perpetually drunk, Swede doesn’t really think about why Corliss likes him. He is, however, perfectly willing to kill Jerry when Corliss claims he raped her. It should be very obvious to you that nothing and no one are as they seem in the novel.

Okay, here’s a confession. I read Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the D’Urbervilles in grad school. I was into the second book when Tess, who was a delicate maiden, started nursing a baby. Instead of remaining in the narrative, I had a million questions. Can women normally nurse if they didn’t just have a baby? Where did the baby come from? It can’t be her baby…right? Whose baby is it?

Dear Reader, I had totally missed the Victorian rape scene in the first section of the book. (The sex, of course, resulted in the baby Tess was nursing.) I believe this is it. Sadly, Alec sexually assaults Tess in this excerpt:

He knelt and bent lower, till her breath warmed his face, and in a moment his cheek was in contact with hers. She was sleeping soundly, and upon her eyelashes there lingered tears.

Darkness and silence ruled everywhere around… But, might some say, where was Tess’s guardian angel? Where was the providence of her simple faith? …

Why it was that upon this beautiful feminine tissue, sensitive as gossamer, and practically blank as snow as yet, there should have been traced such a coarse pattern as it was doomed to receive; why so often the coarse appropriates the finer thus, the wrong man the woman, the wrong woman the man, many thousand years of analytical philosophy have failed to explain to our sense of order. One may, indeed, admit the possibility of a retribution lurking in the present catastrophe. Doubtless some of Tess d’Urberville’s mailed ancestors rollicking home from a fray had dealt the same measure even more ruthlessly towards peasant girls of their time. But though to visit the sins of the fathers upon the children may be a morality good enough for divinities, it is scorned by average human nature; and it therefore does not mend the matter.

As Tess’s own people down in those retreats are never tired of saying among each other in their fatalistic way: “It was to be.” There lay the pity of it.

Now that you’ve read it, am I really so crazy not to have caught what was going on? I wasn’t expecting fifteen pages of graphic description of what Alec did, but I needed a little something more. (Maybe this oversight is a reflection of my highly moral nature.)

Compare that to a naughty scene from Home is the Sailor:

Corliss’ eyes burned into mine. “I love you, Swede. Say you love me.”

“I love you.”

She bit my chest. “Then prove it,” she screamed at me.

“Prove it.”

I did, the hard rock ripping our flesh. We were mad. We had reason to be. We were Adam and Eve dressed in fog, escaping from fear into each other’s arms. And to hell with the fiery angel with the flaming sword. It was brutal. Elemental. Good. There was no right. There was no wrong. There was only Corliss and Swede.

When at last I rolled on my elbow and lay breathless, looking at her, Corliss lay still on her back in the moonlight, her hair a golden pillow, fog eddying over her like a transparent blanket. Her upper lip covered her teeth again. Her half-closed eyes were sullen. The future Mrs. Nelson, I thought, and I wished she had some clothes on.

So this scene is a LOT more graphic than Hardy’s. That much is clear. But look at the subtlety that Keene is employing. He could indeed have done a lot more to describe the lovers’ body parts and where they were going, but he didn’t. What I appreciate is that there’s no ambiguity here. I know that Corliss and Swede are “doing it” and Keene is giving me the interesting details on which I should focus. There’s a light touch here. Keene goes through the main event pretty fast, but lets us know when that part is over. After all, he points out that Swede “rolled on [his] elbow and lay breathless, looking at her.” What a nice detail; Keene treats us the reader like an adult by not shying away from the sex, but focuses more on the emotion and the relationship dynamics at work. There’s a meaningful emotional turn as the afterglow recedes; he confirms that he thinks of Corliss as more than just a plaything. He thinks of her as a wife and as a person deserving of dignity.

Another thing that separates the passage from simple pornography is the poetic touch Keene lends to the scene. Instead of making sex something that is all about the physical movement, Keene makes it into literature and gives us access to Swede’s relatively deep thought about the matter.

What Should We Steal?:

- Don’t confuse your reader by needlessly softening scenes that contain sex or violence. Don’t get me wrong. I don’t blame Hardy for the way he described what happened to Tess. He was writing in a time in which writers were expected to put modesty and propriety above art. (It could be argued that modesty and propriety are enemies of art!) The point is that you can strike a balance between the gratuitous and the necessary.

- Avoid clichés when describing scenes containing sex or violence. Fights and times of lovemaking are unique and meaningful in a character’s life. Therefore, you should endeavor to describe these scenes in as fresh a manner as you can. Keene didn’t say that Corliss’s hair “fell softly on her shoulders.” Can hair fall hard? Where else but on her shoulders? And we’ve heard that before. Instead, he describes her hair as “a golden pillow, fog eddying over her like a transparent blanket.” Pretty.

Fun link: Want to read more about the work?

Novel

1952, Day Keene, Description, Hard Case Crime, Home is the Sailor, Pulp Fiction

Title of Work and its Form: “The Cask of Amontillado,” short story

Author: Edgar Allan Poe

Date of Work: 1846

Where the Work Can Be Found: In any collection of Poe’s works or online. (Isn’t public domain beautiful?) Download the story from Project Gutenberg.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Description

Discussion:

“The Cask of Amontillado” is one of the famous American short stories for a very good reason: it’s awesome. The story is short and sweet. The first sentence sets up the conflict very quickly: “The thousand injuries of Fortunato I had borne as I best could, but when he ventured upon insult I vowed revenge.” The reader knows instantly that the narrator (Montresor) is going to get revenge on Fortunato. The surprise is in the form the revenge will take. Montresor uses Fortunato’s love of wine to lure him into an endless and endlessly creepy underground vault. The dankness of the cellar gives Fortunato a terrible cough; Montresor begs him to turn back. The increasingly drunk Montresor insists they taste the wine that may or may not be Amontillado. Montresor gets his calm revenge. He simply chains Fortunato to a niche in the rocky wall and starts laying brick around him. As the wall goes up and the light goes out on Fortunato, he begs the narrator to let him go. “For the love of God, Montresor.” “Yes,” the narrator calmly says. “For the love of God.” He tosses the torch into Fortunato’s new crypt and slides in the last brick.

Let’s think about intensity and how we depict it. Sometimes, intensity and tension can be created by characters who are loud and angry and bombastic. Think about Samuel L. Jackson. Anyone who writes for him tries to take advantage of how great the guy is at doing INTENSE. Can you read these lines without hearing his voice?

Carl Lee Hailey from A Time to Kill on the stand, testifying about what he wishes for the men who raped his little girl: “Yes, they deserved to die and I hope they burn in hell!”

Jules Winfield from Pulp Fiction, toying with a man who owes his boss money: “English, motherfucker, do you speak it?”

And how many people went to see a movie that was clearly bad only because they knew that they would hear Samuel L. Jackson shout:

“Enough is enough! I have had it with these motherfucking snakes on this motherfucking plane!”

Yes, intensity can be created with high volume and the use of swear words. Tension can also be created without these qualities. Think about the last time your significant other used the silent treatment on you. They weren’t saying a word to you, but they were still driving you crazy. Poe is very effective at creating this quiet intensity in “Amontillado.”

Does Montresor shout and scream at Fortunato? No, no, no. Instead, he pretends to be friendly, offering his friend wine and repeatedly expressing concern for the man’s health. Look at the words Poe uses to describe the beginning of Montresor’s construction project:

As I said these words I busied myself among the pile of bones of which I have before spoken. Throwing them aside, I soon uncovered a quantity of building stone and mortar. With these materials and with the aid of my trowel, I began vigorously to wall up the entrance of the niche.

As in the case of the rest of the story, Poe is offering relatively unadorned, unemotional description. Montresor “busies” himself. While “throw” may be a somewhat intense verb, it’s pretty clear that Poe allows tension to build in a slow manner that is very effective.

Think about it this way. Let’s say one of your characters discovers that their lover is being unfaithful. You could squeeze a lot of drama out of having your character confront the cheater in a belligerent manner. Think of the show Cheaters. The host brings the cheatee to witness the cheater in action. The cheatee gets out of the van, screams, “How could you?” several times, then throws a drink in the cheater’s face. That’s drama, right?

What if your cheatee sits in the dark and sips a glass of whiskey, waiting for hours for the cheater to arrive? No shouting…no screaming. The cheater comes home and is asked some simple questions: “How was your day?” “Where were you?” “How’s that coworker you’re always hanging out with?” See how the tension is ratcheted up? Instead of enjoying the blowup, the reader is on tenterhooks…what’s going to happen? When is the hammer going to fall?

Best of all, if you start out calm, you have the option of getting a lot of drama out of a sudden outburst. This principle can be seen in Pulp Fiction. Think of the scene in which Jules (Jackson) is questioning Check-Out-the-Big-Brain-on-Brad (played by Syracuse native Frank Whaley). The audience knows that Jules is upset with Brad and that SOMETHING is going to happen. Instead of coming in with guns blazing, Jules is cool, asking Brad why the French call the Quarter Pounder a Royale with Cheese and even asking for permission to take a bite of Brad’s Big Kahuna Burger. Jules is calm and is smiling until he shoots the man on the sofa and Brad knows he’s in big trouble. (“Describe what Marsellus Wallace looks like!”)

What Should We Steal?:

- Think of your story like a piece of music; use dynamics. If you start out at full crescendo, there’s nowhere you can go.

- Withhold the proper details from the reader. Poe makes it very clear that “Amontillado” is a revenge story. The reader KNOWS that Fortunato is not going to end up, well, fortunate. Poe creates suspense by making us wonder what the revenge will be.

Short Story

1846, Classic, Description, Edgar Allan Poe