Close your eyes, if you will, and imagine a time when reading prose was the primary way that people consumed stories. (Then open your eyes or else you can’t read this essay.) There was no Law & Order, no NCIS, no NCIS: Dubuque, no NCIS: Portland (Maine). How did people satisfy their needs when they were jonesing for a mystery?

They read mystery books and stories! I know…American culture will never be the same as it was in the good old days in terms of respect for writers and prose, but there are still few pleasures as powerful as cracking open a paperback and sipping a hard-boiled mystery story like a glass of Johnny Walker neat.

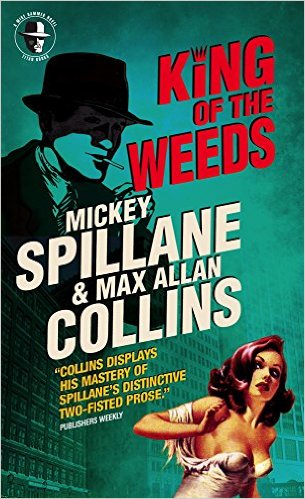

In case you weren’t aware, Mickey Spillane is one of the best-selling authors of all time. He is most famous for the detective he created, Mike Hammer, a private dick who isn’t afraid to use some violence to take some scum off the streets. Mr. Spillane died in 2006 and left a number of manuscripts that he wanted completed by Max Allan Collins, a friend and similarly world-class crime novelist. (I love his Quarry series. Check it out.) One of these unfinished manuscripts was that of King of the Weeds, a novel whose events take place after those of Black Alley. Hard Case Crime/Titan Books is the publisher; they are one of my favorites because they produce great books at a great price and they are keeping the tradition of hard-boiled crime fiction alive.

Yes. I understand that writers such as Mr. Collins and Mr. Spillane will never be considered among the great literary lions. While both authors likely developed back problems from all of the laurels heaped upon them, hard-boiled crime thrillers are not the kind of books that many “literary” people want to glorify. I find this quite sad. Look how much we can learn from the first page of King of the Weeds:

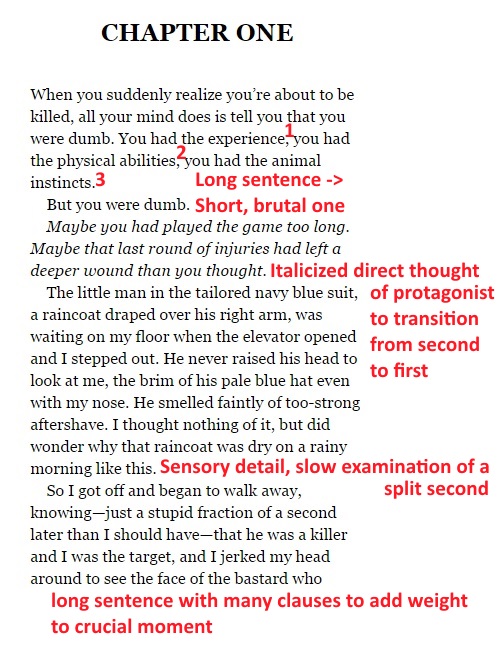

Let’s tally up all of the basic things that Mr. Spillane and Mr. Collins do in these first few paragraphs:

- Establish life-or-death stakes for the narrator

- Employ a little second-person to grab the reader before the first person takes effect

- Depict the hit man that will obviously figure into the narrative

- Remind the reader that Hammer is older than he was and perhaps a step slower, which ratchets up the threat

- Begin the novel in medias res with an attempted murder of the protagonist.

You want to read on, don’t you? Of course you do. I invite you to compare the first page of King of the Weeds to that of the average literary book. Does every book need to begin with an attempted murder? Of course not. But we all do well to introduce big stakes and to do so very early.

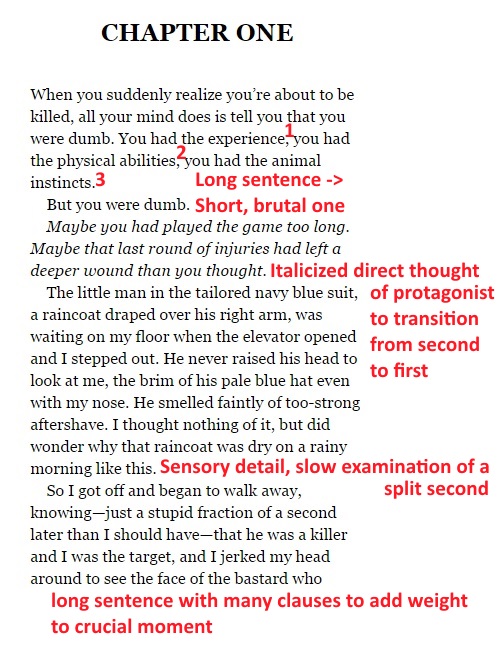

Mr. Spillane and Mr. Collins do a lot of great subtle things in this first page. I’ve marked up the image:

Mr. Spillane and Mr. Collins pull of some beautiful tricks with their prose here. In that first paragraph, they employ the rule of three, establishing a rhythm that carries the reader away-

Mr. Spillane and Mr. Collins pull of some beautiful tricks with their prose here. In that first paragraph, they employ the rule of three, establishing a rhythm that carries the reader away-

only to punch you in the gut with that four-word second sentence. The prose also reflects the rhythm of what Hammer is going through at the moment. His day is about to begin…everything is calm…everything is normal-

gunshot.

Mr. Spillane and Mr. Collins know that the second person “you” bit is a great way to open the book, but they also know that they can’t stay in the second person too long without confusing the reader. How do they ride the line, earning the punch of those first two paragraphs while gently easing the reader into the first person that rules the rest of the book? They use that italicized direct thought from Hammer as an adapter. Isn’t that clever?

I’m reminded of the opening of The Hunt for Red October. No one involved wanted the Russians in the film to speak Russian through the whole film. On the other hand, it always seems silly when people Sam Neill and Sean Connery speak Russian. We all know that neither of those guys speak Russian. But then we wonder why the Russians are speaking English with Scottish inflection. It’s a lose-lose all around. So the writer and director of The Hunt for Red October both acknowledge and work around the dilemma:

In that one quick moment, they say: LOOK. I KNOW YOU DON’T SPEAK RUSSIAN AND THAT YOU PROBABLY DON’T LIKE SUBTITLES. HERE’S THE DEAL. THE FIRST FEW MINUTES WERE IN RUSSIAN, BUT NOW? WE’RE SWITCHING. YOU’RE GOING TO GO WITH IT. OKAY? COOL.

Mr. Spillane and Mr. Collins use that italicized thought from Hammer in the same way to transition: WEREN’T THOSE FIRST TWO PARAGRAPHS COOL? WE KNOW, THANKS. THEY WOULDN’T HAVE BEEN AS COOL WITHOUT THE “YOU.” BUT HERE’S THE DEAL. THE REST OF THE BOOK IS IN FIRST PERSON FROM HAMMER’S PERSPECTIVE, SO LET THAT SINK IN AS YOU READ WHAT WE ARE POINTING OUT IS HAMMER’S FIRST BIT OF EXPLICIT NARRATION.

The fourth paragraph starts to take a little time. Mr. Spillane and Mr. Collins have Hammer walk into an early morning ambush that takes roughly two seconds in real time. That’s not going to work in a novel. Instead, the authors slow things down, dropping a lot of detail about what the hit man is wearing, where Hammer is, what the hit man smells like. The previous prose lets us know we are reading the account of an attack, and the following paragraphs allow us to savor what is happening. (And to pick up clues. It’s a mystery.) The same effect is created in the last sentence here; Mr. Spillane and Mr. Collins give us a fairly long sentence studded with short clauses that create a bumpy, claustrophobic effect that is wholly appropriate to a character being shot.

I acknowledge that I’m often pessimistic and hyperbolic about the things that bother me in the writing community. A great many of my friends enjoy hard-boiled fiction of the kind for which Mr. Spillane and Mr. Collins are justifiably famous. I suppose I make this respectful appeal: if you haven’t read these fun and rip-roaring books before, don’t deprive yourself for long.

Novel

Hard Case Crime, Max Allan Collins, Mickey Spillane, Titan Books

Title of Work and its Form: The Gutter and the Grave, novel

Author: Ed McBain

Date of Work: 1958

Where the Work Can Be Found: The book was originally published as I’m Cannon-For Hire and was credited to Curt Cannon. Feel free to buy an original copy of the paperback. The fine people at Hard Case Crime brought the book back into print in 2005. Why not buy a copy through their Amazon link?

Bonuses: Here is an interview Mr. McBain did with MysteryNet as Evan Hunter in which he discusses writing for Alfred Hitchcock. James Grady wrote this appreciation of Mr. McBain for Slate. Here is an extract from a television program in which Mr. McBain offers his theory as to what happened in the Lizzie Borden case:

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Bridging the Gap Between “Genre” and “Literary”

Discussion:

How can you resist a book when this is the summary you find on the back cover?

Detective Matt Cordell was happily married once, and gainfully employed, and sober. But that was before he caught his wife cheating on him with one of his operatives and took it out on the man with the butt end of a .45.

Now Matt makes his home on the streets of New York and his only companions are the city’s bartenders. But trouble still knows how to find him, and when Johnny Bridges shows up from the old neighborhood, begging for Matt’s help, Cordell finds himself drawn into a case full of beautiful women and bloody murder. It’s just like the old days—only this time, when the beatings come, he may wind up on the receiving end…

See? Doesn’t that sound like a gripping read? Cordell is indeed a broken man who finds himself in a pickle. He’s surrounded by dead bodies, rival pricate dicks who have it out for him and great jazz music. Does Cordell solve the mystery? Does he get over his memories of Toni, the woman his broke his heart? Read the book! (But remember: it’s noir, so things probably aren’t going to end in rainbows and candy canes.)

Mr. McBain promises you a ripping detective yarn and he doesn’t disappoint. Anyone writing in this genre is probably going to tick most of these boxes:

- Close first-person tied to the lead detective

- Authorities who blame the protagonist and who also may be corrupt

- Constant use of alcohol

- Violence

- A femme fatale

- Blunt language peppered with cool and cold terminology

- An ambigious conclusion

The fact that The Gutter and the Grave contains these elements is not a surprise. Here’s what I did find a little bit surprising: I felt the actual crimes (petty theft and two murders) took a backseat to Matt Cordell’s plight and those of the characters he meets in the book.

Think of Dragnet or Law & Order. In general, the writers spend very little time on character development. (There are exceptions, but when you have a very limited run time, you have to focus pretty tightly on introducing the crime, the red herring, the other suspects, the people who know the suspects and then you must offer the reveal of the real criminal.) Yes, Mr. McBain fulfills all of the requirements necessary to make this a hardboiled crime novel. But I really enjoyed the way that the author made me care deeply about Cordell. Toward the end of the book, he devotes several pages to the description of a scene that occurred when Cordell and his ex-wife were happily married. Does this scene relate to the murders in a strict sense? Kinda. But they seemed like a compelling literary departure from the rote nature of an investigation. (Ask questions…talk to suspect…ask more questions of the original person depending on what the suspect told you…)

What’s the lesson? Why not steal the conventions of other kinds of literature for our genre work? Or vice versa? A frequent (and unfair) knock against science fiction, for example, is that works in that genre are focused more on the speculative science than the characters and their situations. Great works of science fiction, of course, are perfectly at home alongside “literary” novels. (Harlan Ellison…Ray Bradbury…Nancy Kress…)

Mr. McBain also avoided falling into the kind of trap that has grabbed me in the past. Even though the book was published in 1958, Mr. McBain avoids using too many references that would date the book. (In fact, I can’t even think of one.) Now, a contemporary reader may have trouble with some of the “pulpy” vocabulary, but that’s his or her problem. Every book contains cultural references that we may not understand.

What are some examples? Well, in 1958, most folks might know what Mr. McBain meant if he mentioned From Hell to Texas, a film that had recently been released. We certainly shouldn’t assume that contemporary readers DON’T know about the film, but most of us might be taken out of the narrative slightly. In the past, I often found myself making jokes or drawing comparisons based upon contemporary references. Some of my great teachers advised me to do so judiciously. And they’re right; how many people today know what Small Wonder is? Who Melanie Hutsell is? What Dope Case Pending means? (It means “obviously the best movie of all time,” but I’m one of the three people on Earth who has seen it.)

What Should We Steal?

- Blend literary conventions with genre work…and vice versa. “Hey, you got character-building flashbacks into my pulp crime novel!” “Oh yeah? Well, you got blunt, enjoyable dialogue into my literary novel!” Yum!

- Avoid making too many contemporary references. These cultural touchstones may not serve your work in the future in the same manner they do today.

Novel

1958, Bridging the Gap Between "Genre" and "Literary", Curt Cannon, Ed McBain, Hard Case Crime

Title of Work and its Form: Home is the Sailor, novel

Author: Day Keene

Date of Work: 1952

Where the Work Can Be Found: The book was republished by Hard Case Crime in 2005. You can also purchase vintage copies at fine secondhand booksellers.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Description

Discussion:

It’s hard to find books that are more exciting than those in the pulp fiction genre. These books are how people got their Law & Order fix before there was Law & Order. The deliciously lurid covers attract attention—an oil painting of a dangerous woman in love-rumpled clothes beckons you—and the characters and situations fulfill our primal need to experience crime and passion. Day Keene was a pulp writer who also wrote suspense radio shows. (You should check those out, too!) Home is the Sailor only takes place over a few days, but those days are very busy! Swede is a sailor just home from a long stretch at sea. He has $18,000 in his pocket and wants to go home to Montana and buy a farm and plant some roots. Unfortunately, he met Corliss, the owner of a tourist stop. Before long, he’s in love. Perpetually drunk, Swede doesn’t really think about why Corliss likes him. He is, however, perfectly willing to kill Jerry when Corliss claims he raped her. It should be very obvious to you that nothing and no one are as they seem in the novel.

Okay, here’s a confession. I read Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the D’Urbervilles in grad school. I was into the second book when Tess, who was a delicate maiden, started nursing a baby. Instead of remaining in the narrative, I had a million questions. Can women normally nurse if they didn’t just have a baby? Where did the baby come from? It can’t be her baby…right? Whose baby is it?

Dear Reader, I had totally missed the Victorian rape scene in the first section of the book. (The sex, of course, resulted in the baby Tess was nursing.) I believe this is it. Sadly, Alec sexually assaults Tess in this excerpt:

He knelt and bent lower, till her breath warmed his face, and in a moment his cheek was in contact with hers. She was sleeping soundly, and upon her eyelashes there lingered tears.

Darkness and silence ruled everywhere around… But, might some say, where was Tess’s guardian angel? Where was the providence of her simple faith? …

Why it was that upon this beautiful feminine tissue, sensitive as gossamer, and practically blank as snow as yet, there should have been traced such a coarse pattern as it was doomed to receive; why so often the coarse appropriates the finer thus, the wrong man the woman, the wrong woman the man, many thousand years of analytical philosophy have failed to explain to our sense of order. One may, indeed, admit the possibility of a retribution lurking in the present catastrophe. Doubtless some of Tess d’Urberville’s mailed ancestors rollicking home from a fray had dealt the same measure even more ruthlessly towards peasant girls of their time. But though to visit the sins of the fathers upon the children may be a morality good enough for divinities, it is scorned by average human nature; and it therefore does not mend the matter.

As Tess’s own people down in those retreats are never tired of saying among each other in their fatalistic way: “It was to be.” There lay the pity of it.

Now that you’ve read it, am I really so crazy not to have caught what was going on? I wasn’t expecting fifteen pages of graphic description of what Alec did, but I needed a little something more. (Maybe this oversight is a reflection of my highly moral nature.)

Compare that to a naughty scene from Home is the Sailor:

Corliss’ eyes burned into mine. “I love you, Swede. Say you love me.”

“I love you.”

She bit my chest. “Then prove it,” she screamed at me.

“Prove it.”

I did, the hard rock ripping our flesh. We were mad. We had reason to be. We were Adam and Eve dressed in fog, escaping from fear into each other’s arms. And to hell with the fiery angel with the flaming sword. It was brutal. Elemental. Good. There was no right. There was no wrong. There was only Corliss and Swede.

When at last I rolled on my elbow and lay breathless, looking at her, Corliss lay still on her back in the moonlight, her hair a golden pillow, fog eddying over her like a transparent blanket. Her upper lip covered her teeth again. Her half-closed eyes were sullen. The future Mrs. Nelson, I thought, and I wished she had some clothes on.

So this scene is a LOT more graphic than Hardy’s. That much is clear. But look at the subtlety that Keene is employing. He could indeed have done a lot more to describe the lovers’ body parts and where they were going, but he didn’t. What I appreciate is that there’s no ambiguity here. I know that Corliss and Swede are “doing it” and Keene is giving me the interesting details on which I should focus. There’s a light touch here. Keene goes through the main event pretty fast, but lets us know when that part is over. After all, he points out that Swede “rolled on [his] elbow and lay breathless, looking at her.” What a nice detail; Keene treats us the reader like an adult by not shying away from the sex, but focuses more on the emotion and the relationship dynamics at work. There’s a meaningful emotional turn as the afterglow recedes; he confirms that he thinks of Corliss as more than just a plaything. He thinks of her as a wife and as a person deserving of dignity.

Another thing that separates the passage from simple pornography is the poetic touch Keene lends to the scene. Instead of making sex something that is all about the physical movement, Keene makes it into literature and gives us access to Swede’s relatively deep thought about the matter.

What Should We Steal?:

- Don’t confuse your reader by needlessly softening scenes that contain sex or violence. Don’t get me wrong. I don’t blame Hardy for the way he described what happened to Tess. He was writing in a time in which writers were expected to put modesty and propriety above art. (It could be argued that modesty and propriety are enemies of art!) The point is that you can strike a balance between the gratuitous and the necessary.

- Avoid clichés when describing scenes containing sex or violence. Fights and times of lovemaking are unique and meaningful in a character’s life. Therefore, you should endeavor to describe these scenes in as fresh a manner as you can. Keene didn’t say that Corliss’s hair “fell softly on her shoulders.” Can hair fall hard? Where else but on her shoulders? And we’ve heard that before. Instead, he describes her hair as “a golden pillow, fog eddying over her like a transparent blanket.” Pretty.

Fun link: Want to read more about the work?

Novel

1952, Day Keene, Description, Hard Case Crime, Home is the Sailor, Pulp Fiction

Mr. Spillane and Mr. Collins pull of some beautiful tricks with their prose here. In that first paragraph, they employ the rule of three, establishing a rhythm that carries the reader away-

Mr. Spillane and Mr. Collins pull of some beautiful tricks with their prose here. In that first paragraph, they employ the rule of three, establishing a rhythm that carries the reader away-