Title of Work and its Form: “Directions: Exit This Burning Building,” poem

Author: Alexis Pope (on Twitter @alexisflannery)

Date of Work: 2013

Where the Work Can Be Found: The poem debuted in Issue 17 of Coconut Magazine. You can read the work here. The poem was subsequently reprinted in Bone Matter, the Lettered Streets Press chapbook that Ms. Pope shared with Aubrey Hirsch.

Bonuses: Here is an interview Ms. Pope granted to Vouched Books. Here is a poem Ms. Pope placed in Guernica. I’ve said it a thousand times: poetry is usually best when heard rather than read. Here’s a video of Ms. Pope reading some of her work:

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Lineation

Discussion:

Well, the meaning of a published poem is determined by the reader, not the poet. I don’t know if Ms. Pope had this in mind, but it seemed to me that “Directions” is a three-section poem about a lover warning another that their relationship may not be a lifetime of wine and roses. Each section features a potent image described in slightly abstract band that keeps the meaning open to interpretation.

One of the reasons I liked this poem is because of the way Ms. Pope plays with the lines. The work in the chapbook is helpful to me (as it may be to you) because Ms. Pope is far more “experimental” than I tend to be. It’s wonderful, isn’t it? If you’re a more “conventional” poet, you can enjoy Ms. Pope’s poem and try to understand how they work in the interest of improving your own work!

Here’s a section of Ms. Pope’s first stanza. (Yes, I was careful to ensure the lineation is the same as in her chapbook; these things can change a little depending on the size of your browser window.)

In the chapbook, the right margins are justified, too. (Darn digital world…) You’ll notice immediately that Ms. Pope has inserted a slash into each of her lines. In case you weren’t aware, a slash is the way you signify a line break in a poem when you can’t reproduce the lines as intended. For example, here’s the first stanza of “Annabel Lee” as it might be quoted under circumstances in which a writer couldn’t reproduce the author’s original lines:

It was many and many a year ago, /In a kingdom by the sea, /That a maiden there lived whom you may know /By the name of Annabel Lee; /And this maiden she lived with no other thought /Than to love and be loved by me.

Ms. Pope could just have hit “return” when she wanted a new line. What does Ms. Pope gain by placing a slash in each of her lines?

- The poem (to my mind) is about the restrictions that we place on ourselves and others in a relationship. Doesn’t a slash make perfect visual sense. That slash is a real barrier to reflect the emotional barrier that may be present.

- The slashes muddy the poem somewhat, allowing (or forcing us) to understand the lines in different ways. Which do we prefer as the first line? “My nose was bleeding this thin way” or “My nose was bleeding this thin way / A napkin arrived in”? Ms. Pope clearly wants to force her reader into a more analytical state of mind.

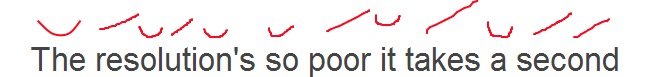

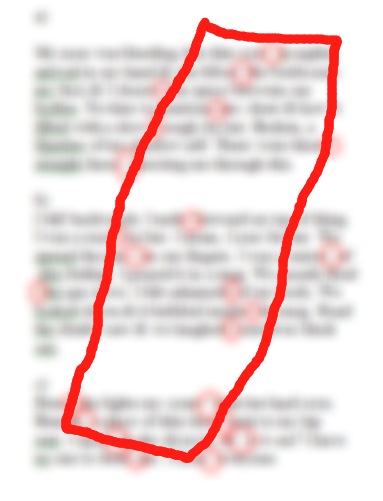

Here’s number 3 and possibly the most fun thing that Ms. Pope gains with her structure. Take a look at the poem with all of the slashes circled in red:

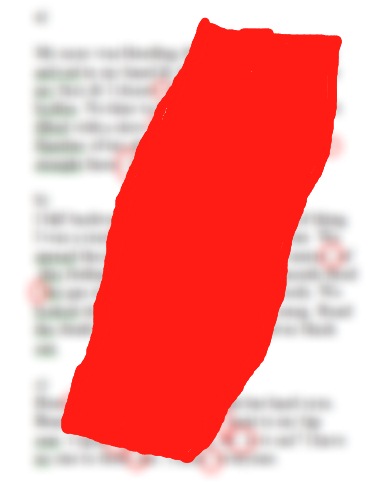

I blurred the words because I wouldn’t dream of reprinting Ms. Pope’s poem without permission. Further, the shape of the slashes take on a form when you’re not thinking of the words, don’t they?

I blurred the words because I wouldn’t dream of reprinting Ms. Pope’s poem without permission. Further, the shape of the slashes take on a form when you’re not thinking of the words, don’t they?

No, the correlation isn’t perfect, of course. But can you allow your pareidolia go to work? The many slashes in the poem create blank spaces that attract your eyes. The poem seems to contain a slash, doesn’t it?

No, the correlation isn’t perfect, of course. But can you allow your pareidolia go to work? The many slashes in the poem create blank spaces that attract your eyes. The poem seems to contain a slash, doesn’t it?

The form of the poem reflects the subject matter, facilitated at least in part because of the way that Ms. Pope uses the slashes in the lines.

The form of the poem reflects the subject matter, facilitated at least in part because of the way that Ms. Pope uses the slashes in the lines.

What Should We Steal?

- Consider the internal structure of your lines in addition to the way they affect the whole. A poem may benefit if the reader is invited to play with and rearrange the lines on their own.

- Allow the form of your work to reflect its specific elements and its theme. A poem that is (to me) about resisting some facets of a romantic relationship can contain slashes…and can also suggest one.

Poem

2013, Alexis Pope, Aubrey Hirsch, Coconut Magazine, Lineation

Title of Work and its Form: “Aneurysm,” poem

Author: David O’Connell

Date of Work: 2013

Where the Work Can Be Found: “Aneurysm” made its debut in issue 4.1 of Unsplendid. You can find the poem here.

Bonuses: Mr. O’Connell was the 2013 winner of the Philbrick Poetry Project‘s chapbook competition. You can purchase his chapbook from the Providence Athenaeum or from Amazon. Here is Richard Merelman’s review of A Better Way to Fall from Verse Wisconsin Online. Here is “Redeemer,” a poem Mr. O’Connell published in Boxcar Poetry Review. Here is “Thaw,” a poem he placed in Rattle.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Lineation

Discussion:

Mr. O’Connell’s poem is a fairly straightforward description of a very sad event. The poem is dedicated to “P.L.,” who lived from 1974 to 2001; we assume that the young man in the poem has died during a very common rite of passage: jumping into a pool from a roof. Through fourteen lines, Mr. O’Connell communicates the sense of loss he felt and connects it to the kinds of loss that we all share.

The first thing that struck me about the poem is the way Mr. O’Connell prepares us for what the poem will do. The title? “Anuerysm.” The dedication? “for P.L. 1974-2001.” What do we learn about the poem from those two elements?

- Tone: the poem probably won’t be upbeat and carefree. Aneurysms are scary and unpleasant and we’re all pretty bummed when people die young.

- Subject matter: we assume we’re going to read an account of the young person’s death.

- Characterization: Mr. O’Connell is a character in the poem; the title and dedication make him seem like a solemn and respectful person…when it comes to this topic, at least. I’m sure Mr. O’Connell has a healthy sense of humor with regard to the appropriate subjects.

Mr. O’Connell introduces the poem in such a manner that the reader feels welcomed. While we all love writing that may be a little more opaque in its meaning, the opening of “Aneurysm” faithfully mimics the approachability of the rest of the text.

I love the way that “Aneurysm” makes use of lineation. It’s my impression that many beginning writers struggle with that jagged right margin. Ending a line is pretty easy when you’re writing prose; you just keep writing. When you’re writing a poem, knowing where to begin again is far more difficult.

Mr. O’Connell demonstrates the power of lineation. Look at the end of the first stanza:

the chimney. Sixteen, he’s on my roof

and then not. Cut by glare, his fall

So P.L. ends that first line on the roof…the reader moves his or her eyes down and to the left…and he’s no longer on the roof. The eye movement mimics the literal movement of the character in the poem. That stanza break also forces the reader into a moment of anticipation, even if that anticipation is subconscious. For that split second, we’re wondering what will come next. Let’s see how the effect would be ruined if we slapped all of the words onto the same line.

…the chimney. Sixteen, he’s on my roof and then not. Cut by glare, his fall…

See? We lose the tension Mr. O’Connell was smart enough to create.

Another great thing about the poem is the way Mr. O’Connell chooses an unanticipated and powerful verb:

the moment he explodes the pool,

Mr. O’Connell had a number of more conventional options:

- jumps

- falls into

- dives into

- drops into

- descends into

- enters

- reaches into

- slips into

Instead, Mr. O’Connell has the protagonist “explode” the pool. Not only do we get an idea of what the narrator must have looked like upon contact with the water, but we get a better idea of how the pool itself must have appeared. Even better, “explode” is a pretty heavy duty word, isn’t it?

What Should We Steal?

- Welcome the reader into the piece. The title and first lines should communicate the tone, intent and subject matter of the rest of the piece.

- Compose your lines in such a manner that you create anticipation and reflect the events of your poem. Lineation is a special instance of cognitive understanding that is shaped by physical movements.

- Employ unexpected verbs. A baseball player can “hit” the ball…or he can “knock,” “slap,” “pound,” “slam” or “drive” the ball.

BONUS BONUS:

I’m not quite sure where this fits in, but the first line of the poem reminds me of what I guess I think of as “poet meter.” Is it just me, or do you hear this meter a lot when you go to poetry readings?

It’s not quite iambic pentameter, but it has that sing-songy quality that draws you in.

Poem

2013, David O'Connell, Lineation, Ohio State, Unsplendid

Title of Work and its Form: “We Real Cool,” poem

Author: Gwendolyn Brooks

Date: 1960

Where the Work Can Be Found: The poem has been anthologized a LOT. You may also find the work in authorized form on the web site of the Academy of American Poets.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Lineation

Discussion:

Many folks are under the impression that poetry must be depressing and must use flowery, ostentatious language. Poems are like people; no two are alike and they come in all possible shapes and colors and permutations. “We Real Cool” does not contain any “big” words; in fact, the poem is deliberately written in the vernacular (commonly used language) of those young pool players. You’ll also notice that all of the words are monosyllabic. Sure, you could make a case that “real” should be two syllables. Listen to Gwendolyn Brooks read her poem and you will see that “real” is only one syllable to her and to the characters she’s writing about.

“We Real Cool” is a powerful example of the way that poetry can make music. The most musical choice that Ms. Brooks makes, it seems to me, is the way she splits up the sentences in her poem. The poem consists of eight sentences, each beginning with “We.” Would the sentences have the same kind of melody if each were placed on its own line with no break? Let’s see what it looks like:

We real cool.

We left school.

We lurk late.

Instead, the first seven lines end in “we.” This choice creates a great deal of momentum in the reading of the piece. Instead of sounding like a grocery list, the poem sounds like a song. If you listen to the reading of the poem, you’ll notice that the “we” sounds a little less important than the words that follow. Isn’t this where the emphasis belongs? The pool players lurk and strike and sing. The reader already identifies them as a group, so we’re much more interested in seeing what the group does.

Think about it this way. Let’s look at a quote from a movie you should see and think of it as a poem. In the following line from the 1954 film On the Waterfront (written by Budd Schulberg and directed by Elia Kazan), Terry Molloy (Marlon Brando) is considering testifying against a gang boss. His brother Charlie, the gangster’s right-hand man, tries to get Terry to forget about testifying. Terry tells his brother:

“You don’t understand! I coulda had class. I coulda been a contender. I could’ve been somebody, instead of a bum, which is what I am.”

What if the “poem” looked like this on the page:

You don’t understand!

I coulda had class.

I coulda been a contender.

I could’ve been somebody,

instead of a bum,

which is what I am.

Or what if it looked like this?

You

don’t understand!

I

coulda had class.

I

coulda been a contender.

I

could’ve been somebody, instead of a bum, which is what

I

am.

Or even like this?

You don’t understand! I coulda

had class. I coulda been

a contender.

I could’ve been

somebody,

instead of a

bum,

which is what

I am.

See how the meaning and the feeling of the poem can be influenced by the way it looks? Gwendolyn Brooks shaped “We Real Cool” as though it were a ceramic sculpture; she made the appearance of the poem reflect the way she wanted it to feel.

What Should We Steal?

- Think about the effect of the shape of your lines. When someone is reading your poem, their eyes are literally moving left to right and down the page. When you “chop up” your lines, you’re forcing the reader to consider your words just a little bit more slowly than they might otherwise. The same technique can be seen in suspenseful stories. The identity of the killer, for example, may not be buried in the middle of a big, thick paragraph. Instead, the important “jolt” may be found at the end of a bunch of really short paragraphs.

- Transfer the music of your poem to the page. If you really thought about it, you might not be surprised the Gwendolyn Brooks read her poem aloud the way she did. You’ve undoubtedly heard that you should read your work aloud to yourself during revision…here’s another reason why. Ask yourself if the words on the page sound the way they do in your head.

Poem

1960, Classic, Gwendolyn Brooks, Lineation

I blurred the words because I wouldn’t dream of reprinting Ms. Pope’s poem without permission. Further, the shape of the slashes take on a form when you’re not thinking of the words, don’t they?

I blurred the words because I wouldn’t dream of reprinting Ms. Pope’s poem without permission. Further, the shape of the slashes take on a form when you’re not thinking of the words, don’t they? No, the correlation isn’t perfect, of course. But can you allow your pareidolia go to work? The many slashes in the poem create blank spaces that attract your eyes. The poem seems to contain a slash, doesn’t it?

No, the correlation isn’t perfect, of course. But can you allow your pareidolia go to work? The many slashes in the poem create blank spaces that attract your eyes. The poem seems to contain a slash, doesn’t it? The form of the poem reflects the subject matter, facilitated at least in part because of the way that Ms. Pope uses the slashes in the lines.

The form of the poem reflects the subject matter, facilitated at least in part because of the way that Ms. Pope uses the slashes in the lines.