Title of Work and its Form: “Breatharians,” short story

Author: Callan Wink

Date of Work: 2013

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story debuted the October 22, 2012 issue of The New Yorker. At the time of this writing, the story was available in full on the New Yorker web site. “Breatharians” was subsequently selected for The Best American Short Stories 2013.

Bonuses: Here is what Trevor Berrett thought of the story. Here is what Teddy Mitrosilis thought. Consider checking out Mr. Wink’s first collection: Dog Run Moon: Stories.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Narrative Structure

Discussion:

August is a young man who is living between two worlds. To paraphrase Britney, he’s not a boy, not yet a man. His mother and father live in separate homes on the same property. His body is strong enough to allow him to kill cats without remorse, but he mourns the loss of his “birth dog.”

The inciting incident of the story is the moment when August’s father tells his son to “get rid of the damn” wild cats in his barn. August is happy to take on the work; he wants pocket money. The story covers the next couple days as the cat slaughter looms in the distance and the reader learns about the protagonist’s situation. It seemed to me as though Mr. Wink was most interested in painting the portrait of his interesting character. There’s an uneasy peace in August’s life: a peace that will be shattered when he finally figures out more about life. Continue Reading

Short Story

Best American 2013, Callan Wink, Narrative Structure, The New Yorker

Title of Work and its Form: Impulse, novel

Author: Ellen Hopkins (on Twitter @EllenHopkinsYA)

Date of Work: 2007

Where the Work Can Be Found: Impulse can be found in independent bookstores everywhere. If you don’t know where to find the indie bookstore closest to you, IndieBound will be happy to point you in the right direction. The book can also be purchased online.

Bonuses: Ms. Hopkins’s site is extremely detailed and the author is very generous when it comes to communicating with her readers. Feel free to interact with other fans of Ms. Hopkins’s work at her Facebook page. Here is an interview that Ms. Hopkins gave to the Monster Librarian.

One of the things I love about YA literature is that fans are so enthused about what they read. Here is a fun video review of Impulse.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Narrative Structure

Discussion:

Tony, Vanessa and Conner are teenagers who are spending time in a psychiatric facility after unsuccessful attempts at suicide. Each of them tried different methods and had different reasons, but they are united in their grief, sadness and need for help. Slowly but surely, each of them reach mutual understanding and help each other address the problems that led them to such drastic measures.

If you listened to my interview with YA author Sarah Tregay, you heard her talk about how much she loves novels written in verse. Ms. Hopkins unspools the plot of Impulse through the course of hundreds of brief poems. Each poem is in first person and Ms. Hopkins cycles through each character every few poems.

Impulse is predicated on a high-concept conceit. Now, I love these kinds of projects-I’ve even completed a few of these works that play with narrative in extreme ways. The big problem when you undertake such a project is that you are making your job a little bit harder. Not only must you fulfill all of the standard obligations of the storyteller (plot, characterization), you must do so while remaining true to the unconventional structure that you’ve assumed. It’s hard enough to hold the reader’s hand through the course of a grand narrative packed with multiple protagonists…Ms. Hopkins challenged herself to take the reader on that same journey, but with her eyes closed!

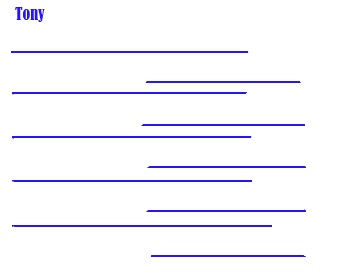

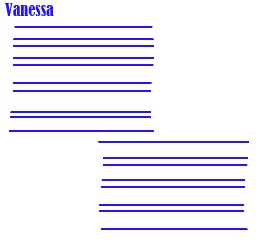

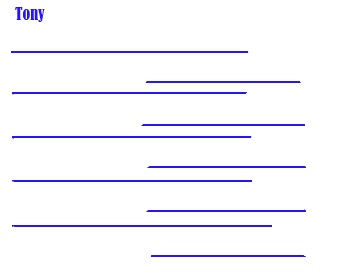

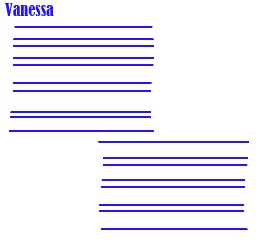

So how did Ms. Hopkins keep everything clear? Well, first of all, she was wise enough to make sure that each character composed poems of different and discernible style. With some exceptions-I’ll talk about those-each character composes poems thus:

The lines of Tony’s poems generally alternate beginning at the left margin and a few tab stops in.

Vanessa’s poems generally consist of brief stanzas. The stanzas, not the lines, alternate between beginning at the left margin and a few tab stops in.

Conner’s poems are generally wrought from short lines, each of which begin on the left margin.

Why is this choice a very shrewd decision on Ms. Hopkins’ part? She gets a number of advantages:

- The reader can quickly (and perhaps subconsciously) understand which poem belongs to which character. Ms. Hopkins doesn’t have a narrator that can say, “Conner said,” so she must let us know who is speaking in another way. This is her way of doing so, in addition to including the character’s name before each section.

- The styles of poetry express the character. Conner begins the story as very strait-laced, so it makes sense that his lines are more “boring.” He SHOULDN’T have “funky” lines because that’s not the kind of character that he is. Tony’s lines are appropriate because he’s always vacillating, alternating between big thoughts in his life about facets of himself that he can’t understand. Vanessa is a little bit closer to self-understanding, but her poems must also express some confusion about herself.

- The patterns break down a little bit as the book goes on. This is a good thing. Why? These changes reflect the changes that are going on in the characters as they learn more about their problems and themselves.

It’s all a matter of “show, don’t tell.” (I know you’ve heard that writing advice before!) Instead of just typing out a TELL: “Hey! Tony understands his sexuality a little more completely now!,” Ms. Hopkins SHOWS you that Tony has become a little more comfortable with his past.

Ms. Hopkins is also careful to adhere to traditional story structure, but does so in an interesting way. I’ll explain. The story of Impulse does indeed follow Freytag’s Pyramid:

The story beats get more serious and more interesting…there’s a final climax…there’s a denouement and an establishment of the new status quo in the characters’ world…great. That’s what a writer is supposed to do. But Ms. Hopkins employs what I’ve decided to call Ken’s Character Onion:

I am aware that I cannot draw, but the point is that Conner, Tony and Vanessa resemble onions. How? They make us cry. Okay, I’m kidding. The characters resemble onions because they each have a number of layers that Ms. Hopkins peels back one by one. In Freytag’s Pyramid, each conflict in the story gets bigger and bigger. In Ken’s Character Onion, each revelation gets more and more dangerous. It’s not enough that the action is increasingly exciting; the stakes for each character must become more imposing.

I am aware that I cannot draw, but the point is that Conner, Tony and Vanessa resemble onions. How? They make us cry. Okay, I’m kidding. The characters resemble onions because they each have a number of layers that Ms. Hopkins peels back one by one. In Freytag’s Pyramid, each conflict in the story gets bigger and bigger. In Ken’s Character Onion, each revelation gets more and more dangerous. It’s not enough that the action is increasingly exciting; the stakes for each character must become more imposing.

Even better, Ken’s Character Onion adds suspense to a story. We care even more deeply about what will happen when we know that the author keeps raising the emotional stakes for his or her characters. Want a great example from the movie world? The 1999 Alexander Payne film Election (based upon the book by Tom Perrotta) begins with a dizzying, hilarious sequence of character-related details. We learn Tracy Flick is running for class president. She is extremely anal about the presentation of her clipboards. Mr. McAllister is put upon by the world; he must clean up the mess his coworkers made before he can put his lunch in the refrigerator. Tracy is a go-getter. Tracy had an affair with her teacher, Mr. McAllister’s friend, Dave Novotny. I know, it’s hard to understand without having seen the film. So go watch the film. Honestly, it’s nearly flawless and you’ll learn a ton.

Think of Freytag’s Pyramid and Ken’s Character Onion as parallel structures that keep a story interesting and a reader engaged. Just like Alexander Payne did in Election, Ms. Hopkins releases plot and character details with enough regularity to keep the reader chugging along.

The last thing we should learn from Impulse is something that I tend to think about whenever I read, write about…or write Young Adult fiction. I love the way that great YA literature deals with big, scary issues and treats its readers like…well…young adults instead of kids. Countless thousands of teenagers engage in the behaviors described in the book. They’re taken advantage of by teachers. They engage in cutting. They lash out sexually because of trauma they suffered in childhood. Perhaps it’s because I had a slightly challenging childhood and adolescence, but I never understood why a parent or authority figure would want to hide reality from a young person. We need to face facts: Teens think about sex on occasion. (Every five minutes.) Teens resist authority figures. Ms. Hopkins remains true to her readers by capturing the world as it is, not how the deluded believe it to be. And I’m willing to bet that Ms. Hopkins has received thousands of letters thanking her for the work she has done to improve lives through literature.

What Should We Steal?

- Allow yourself to work with a big conceit, but fulfill your obligations to your reader. You can write a story that violates every standard convention in the book…so long as you don’t leave your reader behind.

- Employ Ken’s Character Onion when you construct your characters. Little by little, your characters should have more depth and we should know more about their very serious concerns.

- Keep it real. No one is happy, for example, that some people are sexually abused. Depicting the struggle of such a person in story helps victims and non-victims alike to understand the depth of such a violation. (Which results in the empathy that prevents and punishes such sad events.)

Novel

Alexander Payne, Election, Ellen Hopkins, Impulse, Narrative Structure, Tom Perrotta, Young Adult

Title of Work and its Form: “Leap of Faith,” short story

Author: Brendan DuBois

Date of Work: 2015

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story made its debut the February 2015 issue of Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. The fine folks at that magazine have posted an excerpt of this equally fine story.

Bonuses: Here is an interview the author gave to WGBH. Here is his Smashwords page. Want to see Mr. DuBois discuss his work? Sure you do. (What he says is really inspiring!)

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Narrative Structure

Discussion:

I’m not quite sure why, but I devote a lot of GWS focus to “literary” fiction, for whatever that means. I’m guessing I’m not the only one, but I love spending time in the realm of “genre.” Or whatever that means. Mr. DuBois is a fantastic writer of mystery and suspense fiction and we should all be familiar with his work.

This particular story is a first-person piece whose protagonist is named Hank Kelleher. This is a frame story; the first couple pages take place when Hank is an adult. He climbs his way to the old quarry, a place that many people can understand. Isn’t there a similar place in every town? In this particular case, teens exercised their invincibility by drinking beers on the bank of a man-made lake and jumping into the water from three outcroppings of increasing height: Rook, Bishop and King. A police officer questions Hank, giving Mr. DuBois the excuse for Hank to tell the story of what happened when he was young. Hank’s father died when he was young, leaving him the “man of the family.” As a teen, Hank felt deficient in this duty because he couldn’t protect his little sister Kara from Dev Cullen, her abusive rich kid boyfriend. I don’t want to describe all of the fun out of the story. Suffice to say that “Leap of Faith” is tidy, entertaining and powerful.

One of the biggest reasons that “literary” writers should spend more time in the mystery sandbox is because writers like Mr. DuBois excel at creating plots that are utterly fictional, but seem perfectly natural in the refractory period after the story’s final blow. After setting up the frame-believe me, we’ll talk about that frame-Mr. DuBois wastes zero time introducing the story’s characters and central conflict:

The name’s Hank Kelleher, and I was seventeen that summer. And that’s when my fifteen-year-old sister Kara got into trouble. Not that kind of trouble, thank God, but over supper one night Mom had pressed my sister Kara about why she was dating Dev Cullen. “You know he’s just a bad sort,” Mom said, as she slapped dollops of mashed potatoes on the chipped white plates we used, next to the freshly made Hamburg steak. “He and his father Patrick and his damn uncle Blackie. Crooks, all of them. You stay away from him.”

The reader is not asked to wonder what is going on or to break out graph paper to chart the relationships between a thousand characters. Nope. Hank has a baby sister who is dating a bad young man. Everyone understands this situation, regardless of gender, race or age. Instead of wondering what is happening, we’re wondering something more specific: how will Hank save (or try to save) Kara from Dev.

If you are a dedicated GWS reader, you know that I love Freytag’s Pyramid and I love countdowns and other literal representations of its principles. The climax of the story takes place at the abandoned quarry, the place where teenagers go to…well, be teenagers. Mr. DuBois describes the quarry in the introduction of the story. There are three jumping platforms of increasing height: Rook, Bishop and King.

Why do I love the way Mr. DuBois contrived the geology of the story? The quarry’s topography is a literal match for Freytag’s Pyramid.

Like I said, I don’t want to give away too much, but the climax reaches increasing peaks of rising action on all three jumping platforms. The reader gets a moment of excitement…and then the calm as the splash recedes. We’re not wondering anything general about Hank’s motivations; we know he wants to protect his sister. Instead, our curiosity is focused upon a single, specific question: how is Hank’s final plan going to protect his sister and get Dev off of their case? Since the reader’s curiosity is so focused, Mr. DuBois can simply draw out the tension and put us on tenterhooks.

Like I said, I don’t want to give away too much, but the climax reaches increasing peaks of rising action on all three jumping platforms. The reader gets a moment of excitement…and then the calm as the splash recedes. We’re not wondering anything general about Hank’s motivations; we know he wants to protect his sister. Instead, our curiosity is focused upon a single, specific question: how is Hank’s final plan going to protect his sister and get Dev off of their case? Since the reader’s curiosity is so focused, Mr. DuBois can simply draw out the tension and put us on tenterhooks.

I wouldn’t be surprised if Mr. DuBois is also a fan of something I love a great deal: old-time radio dramas. One of my favorite programs is Suspense, which I suppose you could say was a bit like the Law & Order of its day (before the radio version of Dragnet premiered). Every week, the Man in Black would introduce a story. For half an hour, you would get thrills and chills and an ending that you didn’t see coming. (But an ending that makes sense in retrospect.) Here’s one of the best episodes ever, and one that was repeated live several times. It’s Agnes Moorehead in “Sorry, Wrong Number:”

Why should you listen to every episode of Suspense? Because the plots were usually constructed with flawless precision. The writers were expert at trading levels of power between characters. And the nature of radio required an awful lot of first-person narrators and frame stories. (You can’t exactly have long moments of silence on the radio and a third person narrator that zips around a lot would likely be confusing.) So go check out the vast beauty of old time radio.

Okay, let’s talk about that frame. At first, I was wondering why Mr. DuBois began with that present-day introduction and told the real narrative in flashback. I’m thinking about the suspense/crime stories I’ve written and I’m much more likely to begin with the sentences that kick off the flashback, “The name’s Hank Kelleher…” than a passage that is much calmer:

It took me three tries before I found the old dirt road, on the outskirts of the small Massachusetts town where I had grown up. The road twisted and turned, and ended up in a wide turnaround. There used to be a trail that went up a high slope, but now there was a chain-link fence blocking access. Every few feet there was a no trespassing sign, contrasting with trespassers will be prosecuted. I parked the rental car, got out, walked over to the fence.

Why did Mr. DuBois make the right choice? What can we learn? Putting the what-happens-to-Dev story in a frame allows Mr. DuBois to…

- Foreshadow that something significant happened in the quarry and in the Hank-Kara-Dev trio. After all, Old Hank knows what happened.

- Contrast the differences between the eighties and the present-day. The quarry is now filled up, being there attracts the attention of the police.

- Conclude with an ending frame that gives us a “happy ending” of sorts and tells us information to which we would not have access otherwise.

For more proof that Mr. DuBois made the right decision, think about the way the frame functions in the classic Twilight Zone episode, “To Serve Man.” Now, “Leap of Faith” is a very different story, but I think that the structures are similar.

What Should We Steal?

- Ensure that your plots invite your reader to wonder about increasingly specific questions. Think about LOST. At first, we wondered, “Where are they?” After five years, we were wondering, “What’s the Man in Black’s relationship to the John Locke who reappeared on The Island and how does he relate to the Heart of The Island?”

- Employ Freytag’s Pyramid in literal ways. The size of the dragons the hero must fight get larger for a reason…

- Consider trading an extra-punchy first sentence for greater depth and utility of narrative. Freytag’s Pyramid encourages us to employ a slow build in our plots; doing so is sometimes better than an explosive opening sentence or paragraph.

Short Story

2015, Brendan DuBois, Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine, Narrative Structure

Title of Work and its Form: Speak, novel

Author: Laurie Halse Anderson (on Twitter @halseanderson)

Date of Work: 1999

Where the Work Can Be Found: Speak can be found in all local independent bookstores, including Oswego, New York’s the river’s end bookstore. (Ms. Anderson is a friend of that particular store, as well!) You can also purchase the book online from Powell’s.

Bonuses: Here is a cool interview in which Ms. Anderson discusses Speak and the effect it has had on readers for fifteen years.

Want to see Ms. Anderson speak about Speak?

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Narrative Structure

Discussion:

Melinda is not having the best year of her life. That’s to be expected, of course; the young woman is just entering high school. Unfortunately, Melinda has more to worry about than Homecoming and classes. The summer before, she was at a party and found it necessary to call the police. Her old friends are not very happy with her now and she has learned what it feels like to eat lunch alone. Speak chronicles the events of Melinda’s first year of high school. She makes friends with Heather, who loves to make plans. She loves Mr. Freeman’s art class, even if she doesn’t always know how much it means to her. She loves her overworked parents, but Melinda’s secret is making it hard for her to, well, speak to them…or anyone else. By the end of the book, Ms. Anderson reveals the secret and describes how Melinda achieves agency and takes charge of her own life and emotions.

It’s time to do some statistical analysis on the book. I know…I know. We became writers so we wouldn’t have to do math. Too bad; the numbers will help us figure out what Speak can teach us about writing. Like I said, the book takes place over the course of a whole school year. There are four sections, each of which are devoted to one of the year’s marking periods:

| Marking Period |

Pages the Marking Period Occupies in the Book |

Number of Pages |

| 1 |

1-46 |

47 |

| 2 |

47-92 |

45 |

| 3 |

93-139 |

46 |

| 4 |

140-198 |

58 |

What do we notice? Why, the first three secti0ns are virtually the same length! Interesting! The final section is the longest, by far. This is a big deal because the last section SHOULD be the longest. Ms. Anderson spends 139 pages setting up a lot of conflicts and putting a lot of balls into the air:

- What happened to Melinda at the party?

- Why won’t she “speak”/stand up for herself?

- Why does Melinda refer to Andy Evans as “IT?”

- Will Melinda make peace with her old friends?

- Melinda seems to like art…will she stop being frustrated with her art and create a cool piece?

If Ms. Anderson doesn’t answer all of these important questions (and more), we will feel pretty cheated, won’t we? The last section of the book is a little bit longer than the others because the author must pay off all of these conflicts. Explanations take a little bit of time, and they’re often the most satisfying part of a story. Think about the film Titanic. The director, James Cameron, devoted a LOT of that movie’s run time to the couple hours the boat was sinking, right? He did so because he made the same kind of promises that Ms. Anderson made and he needed to fulfill those promises.

Have you ever gone on a vacation? You had to prepare for the vacation, right? You had to pack your bags and save money and maybe even book a flight. This preparation wasn’t the most exciting part of your week off, was it? But when you got to your destination, you wanted to savor every moment. (Just like Ms. Anderson took her time in the fourth section of the book to make sure she answered every question we might have.)

These young kids sat in a car for thirty hours, thinking they were going to “Rattlesnake Ranch.” Their parents did all the preparation and set up the big moment when…they revealed the big secret. They were really going to Walt Disney World!

All those hours in the car may have been fun, but not as fun as the last part of the “story.” The same principle applies to writing. If you were to ask those little girls to write the story of their trip, which section would probably be the longest and most detailed? The Walt Disney World section, of course! The fourth section of Speak is the longest because the author took her time to give you the scenes you were really hoping for.

If you’ve read the book, you’re not a big fan of the character of Andy Evans. For over a hundred pages, you’re not sure why you hate him…you just do. Ms. Anderson couldn’t just tell you why Melinda is scared of Andy from the beginning. Why? Because Melinda wasn’t ready to talk about what happened. (That’s why the book is called Speak!) Instead, Ms. Anderson had to let you know he’s a bad guy in other ways. What are those ways?

- Melinda calls him “IT.” Upper-case letters, so you know she means business. And think about what it means to call someone “it.” They’re not even a real human being when you call them an “it.” Later in the book, she calls him “Andy Beast.” Same thing. Doesn’t sound nice.

- Melinda points out that Andy has a “short stabby name.” Why, that sounds like the kind of thing you say about a bad guy. Say some of the names from the book aloud: Melinda, Heather, Rachel/Rachelle…these all sound pretty calm and “pretty,” right? “Andy Evans” emerges a little sharper on the tongue.

- On page 90 of my edition, Andy arrives at the lunch table. Melinda says, “It feels like the Prince of Darkness has swept his cloak over the table. The lights dim. I shiver.” Again, that’s not the kind of thing you say about a person you think is nice.

- After page 90, Melinda starts mentioning Andy more and more. Page 108: Melinda is scared by the possibility that Andy sent her a valentine. Andy is “definitely not romantic.”

By the end of the book, when Ms. Anderson spills all of the beans, you REALLY know why you hate Andy. But the author keeps your attention and keeps you wondering by making Melinda talk about him the way she does. (Not to mention the fact that Melinda goes from not talking about him at all, to talking about him quite a bit!)

What’s the principle to learn here? Characterization isn’t just about letting us know what to think about a person you create. Characterization also drives the story. Our increasing dislike of Andy lets us know that Andy is pretty important to Melinda’s tale. We don’t know how he relates at first, but we get lots of clues.

It’s a small note, but I love that the book takes place in the Syracuse area. And not just because I grew up in the Syracuse area. Ms. Anderson makes the world of Speak feel real by describing the change of seasons and by populating the story with real landmarks: the big mall in Syracuse, the…interesting downtown retail climate, the dozens of feet of snow the area receives. If you really wanted to do so, you could find a map of Syracuse and chart Melinda’s course throughout the story.

More importantly, Ms. Anderson is making sure that we know her protagonist (the main character, the one who does things) is just like us. We live in a city with popular landmarks. We struggle with a specific kind of weather at times. The world feels real, doesn’t it? This is a principle called “verisimilitude.” That means “the appearance of reality in fiction.” Even though Speak is a made-up story, the book affects us more because it seems real and the events in the book could really happen. (Unfortunately, the central secret of the book happens all the time.)

One last thing. I happen to be finishing up my own Young Adult book (with another in the mental hopper) and I’m really glad that Young Adult books can deal with REAL LIFE issues that teenagers experience. When I was a young adult, I read Judy Blume books-they taught me about all kinds of “mature” subject matter. Unfortunately, Ms. Blume’s books are banned by parents and school administrators all the time. Even an important book like Speak is challenged and banned all the time. I LOVE that Ms. Anderson fights back against grownups who don’t want young people to learn about what people really go through. (Check out this awesome editorial she wrote. Can you tell that she’s all fired up?) My book isn’t THAT “mature,” but I do worry about being hassled by closed-minded folks if it ever gets published.

You might think that we’re made up of molecules and atoms and water and bone and blood. In a deeper sense, we are creatures made up of stories. The stories that we read and hear make us who we are. They teach us empathy for other human beings and light our way when we’re deciding what we want to do with our lives and how we wish to treat people. The next time you hear that someone wants to ban a book, remember: that person is trying to stop you from learning about the world and all of the people in it. After all, a book must be pretty powerful if grown adults are spending time trying to keep you from reading it…

What Should We Steal?

- Set up conflicts and devote a lot of page space to paying off those conflicts. There’s no hard-and-fast percentage of page space you must give to a certain conflict, of course, but it’s important that your reader feels fulfilled by the end.

- Employ characterization in such a way that it pushes the plot along. You will often hear that plot is derived from character. That’s true, but characterization can also advance the plot by itself and make the story seem more real, more “true.”

- Plop your character into a setting that seems real. Remember VERISIMILITUDE (the appearance of reality in fiction). When your characters go to a pizza place, why can’t they go to the same pizza place that you do? (I did this in my own Young Adult book!)

- Strike back against those who wish to ban books. The American Library Association will tell you all about this sad constant in American culture.

Novel

1999, Laurie Halse Anderson, Narrative Structure, Scholastic, Speak, Young Adult

Title of Work and its Form: Forest of Fortune, novel

Author: Jim Ruland (on Twitter @JimVermin)

Date of Work: 2014

Where the Work Can Be Found: Tyrus Books is responsible for publishing the book; why not buy a copy directly from them? Independent bookstores would also appreciate your business. The book is also available from Powell’s and Amazon.

Bonuses: You should definitely check out the site that Mr. Ruland put together for his book. Here is Mr. Ruland’s blog. If you can get over your jealousy, take a look at some of the work Mr. Ruland has published in The Believer.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Narrative Structure

Discussion:

Forest of Fortune is a novel that defies easy categorization and does so in the best of ways. The book is certainly “literary,” for whatever that means. Mr. Ruland has also packed in elements of the supernatural thriller; the titular casino game, for instance, seemed to echo the evil games of chance in the Twilight Zone episodes “The Fever” and “Nick of Time.” The book also confronts a vast canvas; it’s not just the story of three people who have a location in common. Taken as a whole, Forest of Fortune is a somewhat sprawling depiction of a place that is at once sad and joyful, a place where the hopeless cater to the hopeful and most visitors don’t notice the irony that they have traveled to the middle of nowhere to surround themselves with bright, flashing lights and contrived excitement. Whether or not he did it consciously, Mr. Ruland seems to be influenced by the climax and denouement of Poe’s “The Fall of the House of Usher.”

Okay, that’s the fancy-pants way to describe the book. Here’s the way we look at the book if we’re thinking in terms of structural engineering. Forest of Fortune entwines the stories of three people who have a close relationship with Thunderclap Casino, an Indian gaming establishment in a fairly remote part of southern California. (Note: I use the term “Indian gaming” because that seems to be the industry’s preferred nomenclature.)

Here are the third-person protagonists employed by the author:

- Alice - She’s an employee at the casino and is in a precarious position in her life. This change manifests itself in her frequent department shifts and her challenging roommate situation. Even worse, her epileptic seizures seem to be both symptom and cause of her problems.

- Pemberton - The gentleman was a “hard-partying copywriter” in L.A. until his fianceé booted him for excessive drinking, a DUI and her all-around dissatisfaction. He begins the book by interviewing for a position in Thunderclap’s marketing division.

- Lupita - Well, she’s a gambling addict and perhaps an alcoholic. Her sister Mariana has her life together…and Lupita has a close relationship with levers, reels and flashing lights.

…Aaaaand Mr. Ruland throws us a bit of a curveball. The first page of prose is in italicized first-person. This perspective should remain a little bit of a conundrum. It suffices to say that Mr. Ruland shrouds this voice in acceptable mystery and fulfills his obligation to clarify what is going on as the book goes on.

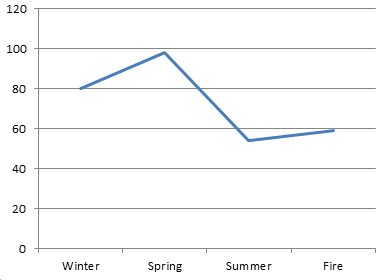

What’s the next thing we do when considering a novel? That’s right. We look at the structure. Mr. Ruland’s doldrums-trapped characters are given several seasons to change:

|

Section Title

|

Pages |

| Winter |

7-86 (80 pages) |

| Spring |

87-184 (98 pages) |

| Summer |

185-238 (54 pages) |

| Fire |

239-297 (59 pages) |

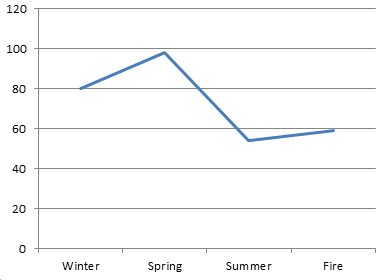

And the next thing we do? We plot the numbers on a graph so we can see a visual representation of the section lengths:

What do we notice? “Spring” is the longest section and the final two are much shorter than the others. Why does this make sense? In “Winter” and “Spring,” Mr. Ruland has a lot of pipe to lay so the end of the narrative will flow. Further, once we get to the climax, we (as readers) just want to go go go and Mr. Ruland shrewdly gives us what we want.

What do we notice? “Spring” is the longest section and the final two are much shorter than the others. Why does this make sense? In “Winter” and “Spring,” Mr. Ruland has a lot of pipe to lay so the end of the narrative will flow. Further, once we get to the climax, we (as readers) just want to go go go and Mr. Ruland shrewdly gives us what we want.

Is a structure of this shape mandatory? Of course not. A storyteller’s First Commandment is that the structure of the piece must, above all, serve the narrative and its characters. The three protagonists (perhaps four, depending on how you look at it) have complicated backgrounds and the author takes the time to throw in a flashback here and there and to give us a complete understanding of who the characters are and why we should care about them.

It’s not fair to say that Forest of Fortune resembles The Twilight Zone exactly. The latter is an idea-driven TV program (often) capped with twist endings and whose plots are as compact as the amount of characterization. The book and the program do have something interesting in common: both feature climaxes that are placed at the VERY end of the piece, leaving very little time for denouement. (The establishment of the characters’ new status quo.)

You probably noticed that the last section of the book is, as they would say on Sesame Street, is not like the others. It’s not the same. The title of the section gives you a little hint with respect to the big event that ushers the characters into a new point in their lives. Why do I bother pointing this out? Such a structure creates a cool effect. Mr. Ruland does not spell out every last detail as to what will happen to the characters. Instead, his characters endure a stressful situation and the reader is given clues to help them divine the futures they have in store.

The same effect can be found in a classic film: 1984’s The Terminator. Sarah Connor, of course, has killed the T-800 and knows she must now bear and protect the man who will eventually fight the machines. She retreats into the countryside. James Cameron offers us a very brief gas station coda in which we’re informed that Sarah has accepted her mission and that she loves Kyle Reese. Then Sarah drives off into the stormcloud-blanketed horizon:

We don’t get a TON of information, but we have a pretty good idea of what Sarah Connor’s future holds…a tough climb in difficult weather.

One of the things I admired most about Forest of Fortune is the way Mr. Ruland uses descriptive imagery. For example:

As Lupita labored up the grade, she wondered why some mountains out here on the outskirts of the desert were jacketed in soil while others resembled piles of boulders stacked by a gigantic hand. Not for the first time she wondered how two mountains could be the same height and shape, but so different. One covered in verdant scrub, the other rocky and barren. They sat side-by-side, inviting comparison. Similar but different, like Lupita and Mariana.

Denise reminded Lupita of her mother, who dealt with people the way a machete sliced through fruit.

Pemberton had no recollection of sending, typing, or even thinking these [text] messages. His bafflement was total, his confusion complete. Did his inner O’Nan send Debra these texts? He was still wearing the name tag from the seminar, only Pemberton had been crossed out, and now it said: LIKE YOU CARE.

So the sentences are pretty. But more importantly, the beautiful language gets work done for Mr. Ruland, putting across plot and/or characterization. I suppose that I’m touching upon one of the big differences between the composition of poetry and narrative. I’m certainly not saying that poets NEVER describe characters or plots. A poem, however, is more likely to be a short burst that places a lot of beautiful responsibility on the reader to interpret meaning. On the other hand, a short story or novel requires each element to serve a far larger whole. It’s like tennis versus baseball: a singles player is fully responsible for getting a win, but a baseball player has several colleagues on whom he must rely for victory.

Above all, Forest of Fortune is a fun novel about serious issues. How can we overcome our big problems? How do we leave behind the disappointments, self-created and otherwise, that have made us miserable? What does it take to get out of the doldrums? Can we simply outrun these problems or are they simply too fleet of foot?

What Should We Steal?

- Analyze the structure of your work to ensure you’re emphasizing the proper parts of the narrative. In general, the work you do to establish your climax should take up many more pages than the climax itself.

- End your work with only the suggestion of future events. Ambiguity, depending on the specific story, can be your friend.

- Charge every element of your story to accomplish narrative work, including description. Stories should have no dead weight; make your sentences multi-taskers.

Novel

2014, Forest of Fortune, Jim Ruland, Narrative Structure, Tyrus Books

Title of Work and its Form: “The Things We Don’t Talk About,” short story

Author: M. Hannah Langhoff

Date of Work: 2014

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story made its debut in Relief: A Christian Literary Expression. You can purchase the issue in print or digital form here.

Bonuses: Here is an excerpt from a piece Ms. Langhoff published in Cicada.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Narrative Structure

Discussion:

What a solid story! Rachel is a fourteen-year-old young woman who has a few problems. Not the least of which is the jerk boy who knocks her down as he rides his bicycle past her. This inciting incident results in Rachel taking Tae Kwon Do classes, where Rachel meets Mr. Cassidy, a high school black belt who teaches her how to protect herself. Rachel’s family is very religious; there is concern as to whether the martial arts lessons are leading her away from her faith. As you really should expect, Rachel learns about herself and her life in the course of the story’s events.

I guess what I love most about the story is that Ms. Langhoff employs a firm structure that makes her intent clear: she wants to tell you a meaningful story about an interesting character.

Let’s see how closely and gracefully Ms. Langhoff adheres to Freytag’s Pyramid:

Inciting Incident: Rachel gets knocked over by the bully.

Complication resulting from the Inciting Incident: Rachel starts taking Tae Kwon Do.

Complications resulting from previous Complication: Rachel meets Jacob Cassidy, a slightly older teacher at the dojang. Rachel sees Diane.

Complications resulting from previous Complications: Rachel shares a significant ride home with Jacob. Diane becomes prominent in her life.

Climax resulting from the Complications that resulted from the Inciting Incident: Rachel encounters the young man who kicked things off in the first place.

Denouement: Rachel’s actions reflect her changed character and self-understanding. Not only is she living in the “new normal,” but she has become the “new Rachel.”

See how beautifully everything comes together? Reading the story just FEELS GOOD.

Ms. Langhoff’s third person narrator is also very powerful and efficient. Check out the very first sentence:

Rachel’s walking along Smith Street, her backpack pleasantly heavy with algebra and sociology and The Call of the Wild, when she hears the buzz of wheels on the sidewalk behind her.

I love the way that the narrator establishes the present tense, the general age of the character, the specter of a threat and the protagonist’s general good-girl attitude. All in one sentence. The narrator is also unafraid to do the real work of the narrator; it skips through time and place at will:

The following Sunday is Rachel’s birthday.

And the narrator is also aware of what is happening in the mind of each character:

What Rachel’s mother doesn’t know, because of their silent agreement, is that Rachel is good.

Even if your narrator is not a “real character,” it’s still a powerful consciousness that is crafting your story. Erin McGraw, a wonderful writer and one of my teachers at Ohio State, reminded me of the narrator’s power with the phrase,

Meanwhile, back at the ranch…

Your narrator can have as much or as little power as is necessary to serve the story you wish to tell. It may also be beneficial to allow yourself to “separate” from the characters and events by thinking about the narrator as a writing partner over whom you have a lot of control.

Another part of the story that I admire is that Ms. Langhoff doesn’t tell us how to feel. Like everyone else, I’m saddened when people mistreat each other. It’s a sad fact of existence. A lesser writer (such as myself), might have enlisted the narrator in judging the sins of the characters. Judgment, however, is reserved for the reader. Ms. Langhoff’s narrator simply recounts events and thoughts, ensuring that the reader feels the power.

The principle is a corollary of “show, don’t tell.” If we follow Ms. Langhoff’s lead and SHOW the reader what is happening and what people are saying and thinking, then the reader is more likely to have an emotional reaction. If we’re TOLD how to feel, it’s probably not going to work.

Here’s a strange example. (Strange examples are more fun than boring ones, of course.) Remember that father who shot his daughter’s laptop to punish her for saying mean things about him on Facebook?

The father’s rhetorical goal was to make his daughter feel bad for not wanting to do chores and for using naughty words. How did he choose to get his message across? With the use of firearms. It seems to me that TELLING his daughter how to feel-and involving firearms-teaches a kid far different lessons. For example, “grownups solve their problems with gunplay.” A heavy-handed third person narrator may not be as effective as one that is a little more hands-off.

What Should We Steal?

- Scale Freytag’s Pyramid. Well-structured stories just FEEL RIGHT.

- Think of your third person narrator as a character with full citizenship in your story. Your narrator is a conduit, but it’s also a version of you in some way. Which strings will you, as the puppet master, choose to pull?

- Leave the analysis for the reader. Okay, we’re ALL bummed that people are sometimes unpleasant to each other. Let us decide how we will feel instead of telling us.

Fun afterthought: I’m amused that the father who shot the daughter’s laptop in an attempt to publicly shame her into behaving appropriately is upset at Dr. Phil for attempting to publicly shame him into behaving appropriately.

Short Story

2014, M. Hannah Langhoff, Narrative Structure, Ohio State, Relief: A Christian Literary Expression

Title of Work and its Form: Looking for Alaska, novel

Author: John Green (on Twitter @realjohngreen)

Date of Work: 2005

Where the Work Can Be Found: The book can be purchased at all fine bookstores.

Bonuses: Mr. Green and his brother Hank are prolific makers of videos; these short films confront a wide range of subjects and are a lot of fun. Find the “vlogbrothers” at their YouTube page. Mr. Green answers a number of questions about Looking for Alaska on his site. (The answers are very intelligent and generous.) You should also know about Mr. Green’s tumblr page. Mr. Green’s work has inspired a lot of very cool young people to do very cool things. Look at this incredible (and pretend) trailer that some folks made for a hypothetical film adaptation of the book:

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Narrative Structure

Discussion:

Miles is a bright young man who is seeking education and enlightenment. This search leads him to leave his Florida home for Culver Creek Boarding School, a place with rigorous educational standards and a lot of brilliant students. The Culver Creek student body is very diverse, especially in terms of socioeconomic status. Miles’s new roommate Chip (The Colonel) is very poor, but some of his classmates are delivered to school by limousine. Whattaya know, Miles meets Alaska, an incredibly beautiful, smart and troubled young woman. Miles joins his new circle of friends in their adventures; he gets in a little bit of trouble and learns an awful lot in his first year in boarding school.

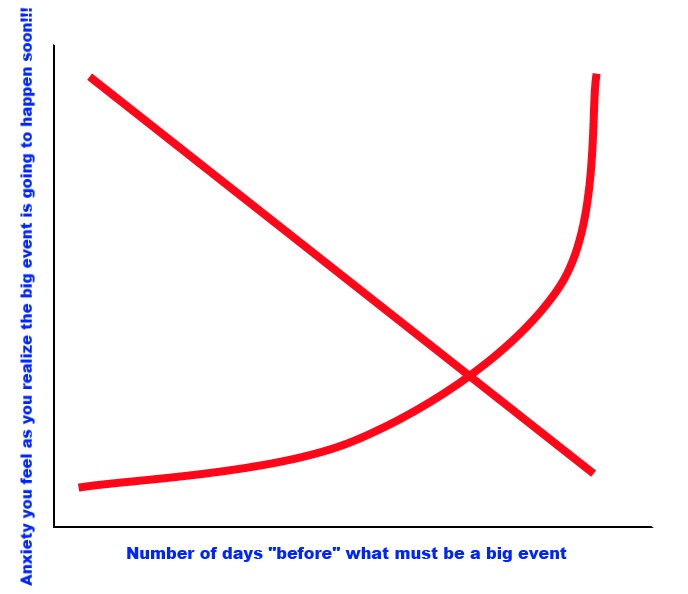

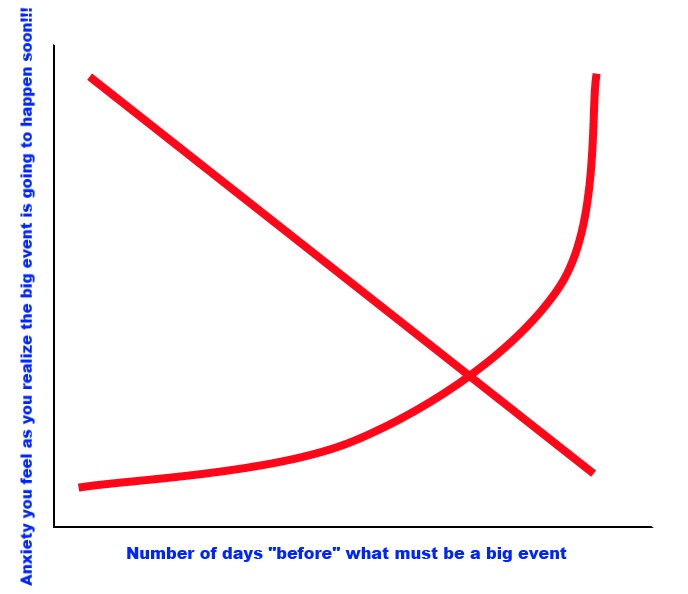

The book has a structure worth discussing. There is a big event that takes place halfway through the book. Each short chapter is labeled to indicate how many days BEFORE or AFTER that event the chapter takes place. Mr. Green has chosen a felicitous way to imbue that big event with importance: A COUNTDOWN. Imagine you’re sitting down to read the book for the first time. You start reading and discover that the first little chapter is taking place “one hundred thirty-six days before.” You’re wondering, “before what?” Before long, Miles/Pudge meets Alaska and the Colonel and Takumi and Lara and that number keeps decreasing. Things are going so well! Miles is learning a lot about life…he’s having a good time with friends…he’s breaking the rules a little bit by drinking and staying up late, but he’s not doing anything TOO crazy…what could go wrong? As the number of days before the big event dwindles, our anxiety increases exponentially. Why? The events are getting bigger. Miles and his friends are planning a big prank and he’s getting closer to Alaska, which is what he wanted all along. Here’s a graphical representation of how we’re feeling as we read:

How does Mr. Green amp up the drama so much? He uses that COUNTDOWN. Dramatists love the countdown because it makes an explicit promise that SOMETHING INTERESTING IS GOING TO HAPPEN. What are some other cool countdowns? The Apollo missions resulted in men walking on the Moon. How did those missions kick off? A countdown, of course. Those decreasing numbers make a promise: once we’re down to zero, there’s going to be a massive and beautiful explosion that (hopefully) propels the spaceship into orbit.

What do we all do on December 31? We sit around the TV and wait until that countdown.

Again, there’s an implied promise. After we get down to zero, there’s going to be a new year ahead of us, one filled with hard work and good fortune. (One hopes.)

The countdown feels right because it’s natural. Each of us spent, give or take, nine months in the womb. Our parents were counting down to the moment we were to arrive. Mr. Green borrows the power of the countdown to make us anticipate the big event that changes the characters; the suspense we feel boosts its power and meaning.

I’m writing a likely-never-to-be published Young Adult novel, so I’ve been reading a bunch of them. (Makes sense, doesn’t it?) I grew up reading books by great writers such as Judy Blume and Bruce Coville. What’s just one thing that Mr. Green has in common with these two? They treat young adults, well, like adults. It has been a few years since I was a young adult myself, but boy, do I remember Teenage Ken and what was happening around him. While I did not drink underage (not that I want a medal), I was somewhat aware that it was happening around me. Some of my classmates were doing drugs, legal and otherwise. Many of them were having sex and most of them really wanted to. Mr. Green allows his young adult characters to act, talk and think in a manner that is realistic for young adults. It took a few pages, but I was happy to see the first “naughty” word in the book. I love that Miles falls quickly and deeply in love with Alaska because that’s exactly what young adults do. (And Alaska was totally my thing when I was seventeen: smart, fun, pretty and damaged enough to understand my damage? I wouldn’t have been able to resist falling in love with her!)

As I expected, Looking for Alaska has been challenged by parents and administrators. Why is this crazypantslooneycounterproductivetosociety? A story that doesn’t feel real is not going to affect the reader. A great work must somehow create the appearance of reality in fiction. This is a concept called verisimilitude. Let’s say you’re late to work. Your boss asks you why you are late and you tell him or her:

It was the craziest thing. I was driving here-on time, I might add-when I saw this bright light ahead of me. It was an alien spaceship. All of a sudden, I was on board and they were doing all of these funny experiments on me. But it wasn’t all bad; they took me out to Pluto and showed me mountains made of diamonds and let me watch a game of Space Baseball before they zapped me back into my car.

The boss is not going to believe your story. Why? Because it does not have the appearance of reality. Nor does a story focused upon dozens of teenagers that is devoid of drinking, smoking, sex, defiance of authority, staying up late and lying to parents.

No, friends, being late to work requires you to come up with a story with much more verisimilitude. So, you were late to work because you overslept. But you don’t want to come out and TELL YOUR BOSS you have trouble getting up on time. What cover story can you tell that FEELS real?

Hey, I’m so sorry. One of my tires was really flat and I simply couldn’t get here without taking the time to fill it up a little.

See? Makes sense. Realistic. It happens every day. (It happened to me not too long ago.) Above all, it’s our job to serve the reader, not to write books according to the desires of people who aren’t going to want to read the work anyway.

Miles/Pudge and his friends have a nemesis, of course. The Eagle is the dean of students. He sees everything that goes on and doles out punishments accordingly. The characters (quite appropriately) see him as something of an out of touch and needlessly authoritarian figure. After all, he busts them for smoking, sends them to Jury and spends his days trying to ruin their fun. And there is a big threat; he already expelled two people last year for three big Culver Creek sins.

When you’re young, it’s tempting to think of authority figures as something other than a real person. As a robot who only serves a function. Ever see Police Academy? If not, you should. Captain Harris is (pretty much) an authoritarian jerk who just wants to make life hard for the protagonists/heroes of the film. See?

Dean Wormer from Animal House-seriously, go watch that one right now if you haven’t seen it-is primarily a one-dimensional jerkface.

I grew to love The Eagle because Mr. Green slowly builds him into a real character. In the beginning of the novel, of course, The Eagle must be a jerk. He needs to lay down the law. He can’t show any soft underbelly because he needs to be seen as an authority figure.

Maybe it’s just because my own YA years look so small in my rear view mirror, but I identified with The Eagle a little bit. He’s not TOO MUCH of a jerk. More importantly, he’s not mindless or heartless. He knows that you have to let young people get away with a little bit. Adolescence is about learning how far you can bend the rules without breaking them and ending up in REAL trouble.

102 days “after,” the main characters play a prank on the school. I don’t want to ruin anything, but it’s a good kind of prank: no one gets hurt, no property gets damaged. The Eagle knows darn well that Pudge, et. al. are responsible for the prank. Does he expel them? Does he punish them? No. He knows that adding to their grief would be counterproductive and that the prank is part of the process by which they are recovering by the book’s big event.

Characters (usually) shouldn’t be all good or all bad. The Eagle is an immovable authority figure/narrative obstacle most of the time, but Mr. Green very wisely gives him a couple moments that reveal his deep humanity. Mr. Green is in great company. Another writer who refused to turn his law enforcement officer into a one-dimensional cartoon character was Victor Hugo. We love Javert (from Les Miserables, obviously) because the events of the book change him and reveal the very human struggle inside him.

What Should We Steal?

- Recognize the natural countdowns around us and use them in your work. If you’re in the Northeast, Winter will give way to Spring. Sure, there may be two feet of snow on the ground and the temperature may be in the single digits…but that is going to change at some point.

- Respect your audience by giving your work verisimilitude. Readers won’t like your work unless your fictional piece offers the appearance of reality.

- Imbue all of your characters with humanity and give them a moment or two in which they can express it. The best heroes have flaws and the scariest villains have virtues.

Novel

2005, John Green, Looking for Alaska, Narrative Structure, Young Adult

Title of Work and its Form: The Three-Day Affair, novel

Author: Michael Kardos (on Twitter @michael_kardos)

Date of Work: 2012

Where the Work Can Be Found: The book was published by The Mysterious Press, an imprint of Grove/Atlantic. You can find it at your local independent bookstore. If you don’t know where your closest indie shop is, check here. I got my copy from The River’s End Bookstore in Oswego, NY. The book can also be ordered online, of course.

Bonuses: Here is what some smart guy thought about Mr. Kardos’s story, “Maximum Security.” (Oh, wait. That was me.) Here is Mr. Kardos’s interview with Brad Listi on his Other People podcast. Here is a very good review of the book from Spinetingler.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Narrative Structure

Discussion:

Will, Jeffrey, Evan and Nolan have been lucky enough to remain friends since their Princeton days. Sure, they don’t see each other very often. Getting together is hard; Jeffrey is a dot-com zillionaire, Evan is a hard-charging lawyer, Nolan is on his way to taking over Missouri politics and Will…well, Will is doing better. He witnessed his bass player get shot and killed in drive-by crossfire. He’s busy running a New Jersey music studio. No matter their busy schedules, the four men always make time for each other; they spend a week playing golf, eating steak and touching base.

Everything is great! Until the INCITING INCIDENT. (Or the turning point of Act One.) Jeffrey needs to get something from a convenience store, so they pull in. In a couple minutes, Jeffrey shoves the young clerk into the car and shouts, “Drive!” Will drives. This is a mystery/noiry-type book, so I don’t want to say too much more. Just read the book if you haven’t already; it’s great!

So, I don’t ordinarily like to create GWS essays about writers I’ve already featured. There are so many great storytellers out there and I want to feature as many of them as I can. On the other hand, I really liked the book and this is my site and I can do whatever I want. (I can’t really say that about too many other facets of my life.)

Mr. Kardos is probably quite justifiably proud of the favorable note The Three-Day Affair received from The New York Times Book Review. One of Ms. Stasio’s comments challenges me with respect to my experience with the book. “The plot,” she writes, “is original, if distinctly bizarre.” Now, I’m certainly not engaging in a respectful disagreement with someone like Ms. Stasio, someone with tremendous qualifications. I’m just not sure how I feel about her description of the plot, as the basic structure felt very familiar to me. In the prologue, we learn about the first-person narrator (Will) and what led him to move from New York City to the ‘burbs. The dramatic present picks up in Chapter 1. And Chapter 1 is pretty sweet. The four men care for each other deeply…they’re making good money…most of them have loving wives…Will is going to be able to start his record label…all is well.

Then boom-page 25 brings the kidnapping that starts the actual plot.

It’s certainly not a knock on Mr. Kardos or Ms. Stasio, but the book employs the tried-and-true structure for a noir/thriller/mystery.

- The first 100 pages of The Firm are great. Mitch is making money, he and Abby have a great relationship; all of his hard work is paying off. THEN THOSE TWO ATTORNEYS GET KILLED.

- In Strangers on a Train, Guy has his normal life. Sure, he’d like to ditch his wife, but things are looking up with the senator’s daughter. THEN BRUNO PROPOSES THE CRISS-CROSS MURDERS.

- Jimmy Stewart broke his leg, but things could be worse. After all, Grace Kelly is his girlfriend. THEN HE STARTS SEEING ALL OF THAT CRAZY STUFF OUT OF HIS REAR WINDOW.

- Marion Crane can’t afford to get married, but at least she has a boyfriend, a good job, a trusting boss…THEN THAT RICH GUY COMES IN AND PLOPS FORTY GRAND IN HER LAP.

- Will, Jeffrey, Evan and Nolan have their health, they ostensibly have a little money, they’re getting together for a week together. THEN JEFFREY SNAPS AND KIDNAPS THAT GIRL.

If you’ll notice, the THEN often happens around the Page 25 mark, just as the THEN often occurs around the MINUTE 15 or MINUTE 30 mark of a film. The book also mildly reminded me of the excellent 1998 film Very Bad Things. Here’s the trailer:

So five guys head to Vegas for a bachelor party. Then one of the guys accidentally kills the young lady who has come to “dance” for them. So the murder is an accident and the other four men are more complicit with each moment that passes. Should the guys protect their friend or go to the police? How do they handle their “105-pound” problem?

Like Very Bad Things, The Three-Day Affair does something wonderful. The characters are placed into a situation that tests their senses of morality. The stakes are constantly raised, of course, so what seemed okay two days ago (driving away from the store) becomes nothing in comparison with what seems okay in the present. Mr. Kardos’s book uses the changing dramatic situation to ask a number of important questions:

- How far would you go to help a friend?

- What’s more important? Your family or your good name?

- How do you get people to forget or to live with the bad things you’ve done to them?

- What’s the proper price of betrayal?

Mr. Kardos certainly doesn’t neglect his primary obligation; he tells us a rip-roaring story that you won’t forget for a while. But he does encourage the reader to consider deep and important thoughts. Will any of us, for example, be in the same situation as Mike McQueary, the man who walked in on Jerry Sandusky, well, raping a small boy? Probably not. (Thank goodness!) We will, however, be confronted with moral and ethical dilemmas that test us. What do we do in the moment? What do we do an hour later to atone for our failings in the moment already passed?

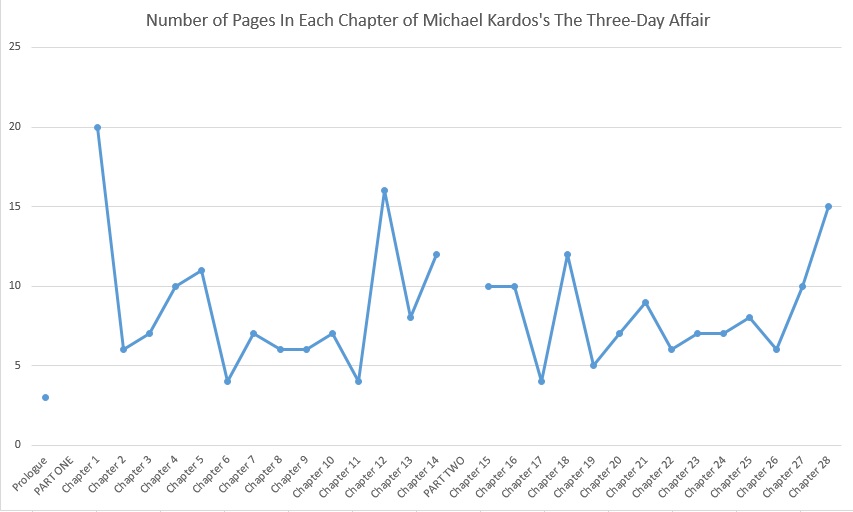

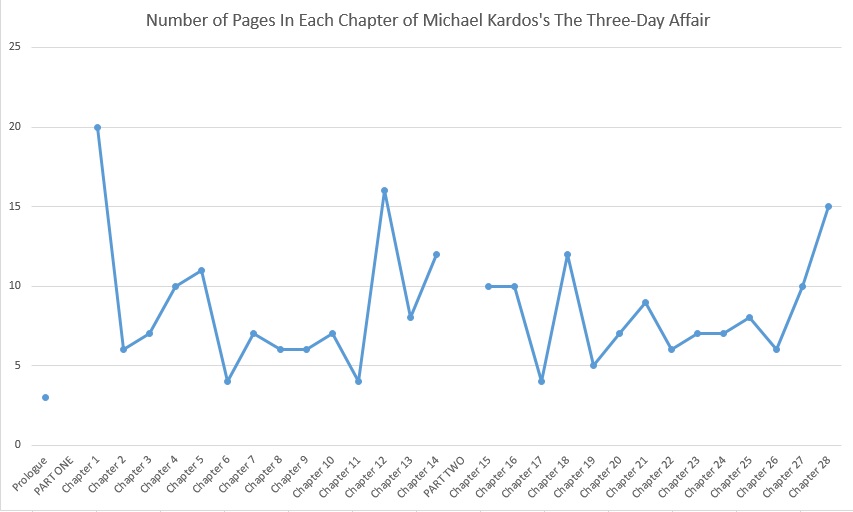

The world-class writer and teacher Erin McGraw would advise us, I think, to abandon our mistrust of numbers. (We are writers, after all.) So I’ve counted the length (in pages) of each of The Three-Day Affair‘s chapters.

Prologue: 3

PART ONE

Chapter 1: 7-26 (20)

Chapter 2: 27-32 (6)

Chapter 3: 33-39 (7)

Chapter 4: 40-49 (10)

Chapter 5: 50-60 (11)

Chapter 6: 61-64 (4)

Chapter 7: 65-71 (7)

Chapter 8: 72-77 (6)

Chapter 9: 78-83 (6)

Chapter 10: 84-90 (7)

Chapter 11: 91-94 (4)

Chapter 12: 95-110 (16)

Chapter 13: 111-117 (8)

Chapter 14: 118-129 (12)

PART TWO

Chapter 15: 133-142 (10)

Chapter 16: 143-152 (10)

Chapter 17: 153-156 (4)

Chapter 18: 157-168 (12)

Chapter 19: 169-173 (5)

Chapter 20: 174-180 (7)

Chapter 21: 181-189 (9)

Chapter 22: 190-195 (6)

Chapter 23: 196-202 (7)

Chapter 24: 203-209 (7)

Chapter 25: 210-217 (8)

Chapter 26: 218-223 (6)

Chapter 27: 224-233 (10)

Chapter 28: 234-248 (15)

And you know I love my literature-related charts:

What’s the point of all of this math-type stuff? Well, you can really see into Mr. Kardos’s thought process with regard to plotting. Look at the anomalies. There must be a reason Chapter 1 is so long, right? Well, he’s setting up the relationship between the men and painting a happy relaxed scene…so he can shake things up with Jeffrey kidnaps the girl.

Why is the last chapter so long in comparison? I’m going to be a bit vague, but the very beautifully written scene offers a motivation for the events of the whole book while complicating the narrative.

I should also point out that the line often looks like a roller coaster. Why would that be? You follow a fat Pope with a skinny Pope. The longer scenes tend to consist of high-octane suspense and the shorter scenes are a lot calmer connective scenes that prepare the next jolt.

What Should We Steal?

- Appropriate the structure of the classics. Look: Psycho worked in 1960. It works now and it will work a hundred years from now. You start out with a sunny and very normal day…then you bring in a lot of complications.

- Confront your reader with a series of deep moral dilemmas. Great drama comes from asking your audience to debate right and wrong.

- Consider the length of your chapters and scenes. Are you giving your reader enough time to recover from the gut punches you’re doling out?

Novel

2012, Megan Abbott, Michael Kardos, Narrative Structure, Noir, Ohio State, The Three-Day Affair

Title of Work and its Form: “Chapter Two,” short story

Author: Antonya Nelson

Date of Work: 2012

Where the Work Can Be Found: The short story was first published in the March 26, 2012 issue of The New Yorker. Subscribers can read the story here. The story was also selected for Best American Short Stories 2013 and can be found in the anthology.

Bonuses: Here is a Q&A in which Ms. Nelson discusses her story. Here is an interview Ms. Nelson granted to The Missouri Review. Here is what Karen Carlson thought of the story. Whoa! Here’s a video of Ms. Nelson reading her story!

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Narrative Structure

Discussion:

Hil is an alcoholic. Is there any better storyteller than an addict who consumes a substance designed to release inhibitions?Hil is tired of her own life, so she enjoys talking about that of her neighbor, Bergeron Love (great name). Bergeron is a kind of Blanche DuBois character, a little bit older and quite sure about what the world should be like. (And how others are falling short of her standards.) Discussing her neighbor also seems to be a way for Hil to distract from her own issues. Bergeron is certainly an interesting character; she’s always calling the police on other people in the neighborhood or running around naked. As you might expect, her son Allistair isn’t very jazzed about the latter. Sadly, Bergeron Love doesn’t survive the story. After we learn of the death, the reader is told more about how Hil lies at A.A. meetings; she leads a dual life. Outside of meetings, she’s a drinker. In the group, she’s been sober for nearly a year. The last few paragraphs center upon how Hil has contextualized the Bergeron Love story and what she thinks may become of Allistair.

Do I love the idea of using the storytelling tendencies of an addict to facilitate a story? Sure. But what I love most about the opening piece is the way Ms. Nelson slid between the meetings (the dramatic present) and the flashbacks to the events she was describing. The technique gave me the feeling that I was reading a prose version of a TV clip show. What’s a clip show? It’s an episode of a TV program in which the dramatic present is broken up with video taken from earlier episodes of the show. Doing a clip show is a great way to save money-you only need to write and shoot a few minutes of narrative-but they can also be boring. Here’s an example of what I’m talking about. The Dick Van Dyke Show is one of the best in television history. In 2004, the living cast reunited to update all of us as to what the characters have been doing since the show ended. Look what happens after all of the characters get together.

“Hey, Alan. Remember that time Laura told everyone you were bald?”

Doodle-oodle-oo…doodle-oodle-oo… We see the footage in which Laura tries to apologize.

“Hey, Rob. Remember that time you broke your leg skiing after insisting to Laura you’d be fine?”

Doodle-oodle-oo…doodle-oodle-oo… We see the footage in which Rob tries to pretend his body isn’t in massive pain.

Now, I’m not saying that Ms. Nelson is relying upon a creative crutch. (Many TV programs that do clip shows are doing just that.) What I am saying is that I love the way Ms. Nelson mimics the structure of a clip show. Check out the beginning of the story. Hill is in the middle of telling a story:

Tired of telling her own story at A.A., Hil was trying to tell the story of her neighbor. It had been a peculiar week. “So she comes to my house a few nights ago, like around nine, bing-bong, drunk as a skunk, as usual, right in the middle of this show my roommate and I are watching.”

Now look what happens in the next paragraph:

“Looks like somebody’s not getting enough attention,” Hil had murmured as she unlocked the door.

Can you spot it? How Ms. Nelson transitioned between the dramatic present and the “clips” in the clip show? Okay, here’s the answer. Ms. Nelson’s narrator employs a different tense. She goes from the past tense to the past perfect.

Past: Hil was trying to tell the story.

Past Perfect: Hil had murmured…

Switching between the A.A. meeting and the events for which Bergeron was present may have been very confusing in the hands of a lesser writer. (Such as myself.) Instead, Ms. Nelson allows her narrator to switch up the tense, efficiently communicating what was happening and when.

Ms. Nelson is indeed playing with time a lot. One of her big responsibilities in the story is to make sure we know where the characters are and when. Look what Ms. Nelson says halfway through the story when she wants to zip around through the space/time continuum:

On that earlier naked night…

Erin McGraw was one of my world-class and extremely generous teachers at Ohio State. I had already understood the principle subconsciously, but she knocked the point home: fiction is great because you can simply type a phrase such as the one I’ve just spotlighted.

Meanwhile, at the ranch…

Having just set her barn on fire, Alexia arrived at the rock climbing facility with a new sense of purpose…

After eating dinner, Bob and Laura got into their spaceship and parked at Mars (Literally) Bars for dessert.

If a scene is getting boring? End it and start another. If you need your character to travel from Portland, Maine to Portland, Oregon? Not a problem. Yes, your choices need to make sense, but all superpowers must be wielded with discretion.

What Should We Steal?

- Employ different tenses to slide between flashbacks and the dramatic present. Telling people that you’re messing around with the dramatic present doesn’t have to be clunky. Remember, on clip shows, the characters will often stare into the camera and say, “WOW. WE HAVEN’T FOUGHT THIS MUCH SINCE THAT TIME WE GOT LOCKED IN THAT WALK-IN COOLER TOGETHER.” Doodle-oodle-oo…doodle-oodle-oo…

- Assert the fiction writer’s control over space and time. Prose writers can easily fast-forward past the boring parts or simply plop your characters where you want them to go.

Short Story

2012, Antonya Nelson, Best American 2013, Chapter Two, Narrative Structure, The New Yorker, Time Travel

Title of Work and its Form: “Lawrence Welk is Dead,” creative nonfiction

Author: Georgia Kreiger

Date of Work: 2012

Where the Work Can Be Found: The piece first appeared in May 2012’s Issue 20 of Front Porch, a cool journal out of Texas State University’s MFA program. You can read Ms. Kreiger’s work here.

Bonuses: Here are two poems Ms. Kreiger published in 2River. Here is another piece of Ms. Kreiger’s creative nonfiction that appeared in Hippocampus Magazine. Here is a fun poem Ms. Kreiger placed in The Cobalt Review. Oh, how cool. Ms. Kreiger was featured in the Saturday Poetry Series of As It Ought to Be, a very good site.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Narrative Structure

Discussion:

Ms. Kreiger’s piece centers upon a phone call she shared with her elderly mother. (Perhaps the call in question is a composite of many; who knows?) The mother/daughter relationship is not exactly the strongest between the two. Ms. Kreiger accepts that she is a “bad daughter,” but she’s not wholly to blame. Years of conflict have soured her on “the mother who could never be satisfied, the mother whose demands packed a punch.” Ms. Kreiger’s mother is watching Lawrence Welk and even this choice becomes a source of conflict between the two. Mom dislikes contemporary music and culture; daughter needs something a little zippier in a television program than the champagne orchestra. Climax: Ms. Kreiger realizes that her mother doesn’t quite realize that the program she’s watching is a rerun and that Welk has been dead for several years. (He died in 1992, in case you’re curious.) Ms. Kreiger laments her mother’s continued mental deterioration and guesses she will someday share the condition. At some point, her unpleasant real memories of her mother will be replaced by a pleasant fantasy in which her mother and Lawrence Welk “waltz lightly across a dance floor gazing lightheartedly into each other’s eyes in a world unreachable by cynics.”

So, “Lawrence Welk is Dead” is not a very long piece at all. As a result, Ms. Kreiger must address the opportunities and risks inherent in composing such a piece. (An obligation, of course, that applies to any writer scribbling out any piece.) What are some of the choices Ms. Kreiger must make because she only has several hundred words at her disposal? Well, she can’t exactly do a lot of scenework and can’t fully describe a vast number of scenes. She just doesn’t have time. The point of the piece must be meaningful and important, but can’t exactly be vast or comprehensive. There’s a reason why Les Miserables takes up hundreds of pages and this piece only takes up a couple.

Ms. Kreiger structured her piece in a shrewd and felicitous manner. There’s really only one scene: she calls her mother, who is watching Lawrence Welk on TV. This compact nugget of narrative allows her to comment on her life and relationships in more abstract kinds of ways. Ms. Kreiger seems to be working on a full-length memoir; I’m betting there are TONS of scenes in her manuscript. There are likely lots of extended dialogue scenes and beautifully written paragraphs about places and objects that have had a critical effect upon the woman she has become. This amuse-bouche, however, can’t be as complicated or as comprehensive as a ten-course meal.

Let’s take a look at the general outline of the piece. Ms. Kreiger employs a common and appropriate structure. In the first sentence, she tells us that she’s calling her mother on the phone and we’re guessing the title has something to do with the “news” she mentions. Then there’s a recap of the standard conversations they have: lamentations about rising gas prices, discussions about the new clergyman at the church. With the ordinary stuff out of the way, Ms. Kreiger gets into the talk about Lawrence Welk and the generational differences between the two. This is the conflict in the piece and it builds until Ms. Kreiger points out that her mother has forgotten that Welk died a while ago. She mentioned the memory loss before, but seeing it in the dramatic present allows her to finish the piece with a two-paragraph fantasy that allows her to pull back and offer a wider look at her life and her perspective. Think about the end of a movie. Having overcome the star-crossed beginning of their love affair, the protagonists are in a hot air balloon and are throwing money into Central Park. Ms. Kreiger employs what I call a “crane shot conclusion.” Here’s what it looks like in a movie:

The protagonist of the film seems to get smaller from the reader/viewer’s perspective. More importantly, the main character, with whom we’ve empathized for ninety minutes, seems to melt away into the rest of society. Everyone in the world has their own concerns and needs, right? Ms. Kreiger’s “fantasy” about her mother dancing with Lawrence Welk leads us by the hand from the specific narrative and into a greater truth. See? Simple and classic, but effective.

What Should We Steal?

- Restrain yourself from trying to cram massive and complicated scenes into brief pieces-and try not to devote tons of pages to simple scenes. Don’t be the person at the party who takes half an hour to tell the story of how they bought a non-fat latte and received a latte made with 1%.

- End your piece with a “crane shot conclusion” when appropriate. You’ve told us about one specific situation involving specific human beings…maybe you should wrap things up by departing from strict realism and a strict focus on those human beings.

Creative Nonfiction

2012, Front Porch, Georgia Kreiger, Lawrence Welk, Narrative Structure

What do we notice? “Spring” is the longest section and the final two are much shorter than the others. Why does this make sense? In “Winter” and “Spring,” Mr. Ruland has a lot of pipe to lay so the end of the narrative will flow. Further, once we get to the climax, we (as readers) just want to go go go and Mr. Ruland shrewdly gives us what we want.

What do we notice? “Spring” is the longest section and the final two are much shorter than the others. Why does this make sense? In “Winter” and “Spring,” Mr. Ruland has a lot of pipe to lay so the end of the narrative will flow. Further, once we get to the climax, we (as readers) just want to go go go and Mr. Ruland shrewdly gives us what we want.