Friends, Sarah Yaw is a longtime friend of Great Writers Steal. If you haven’t already done so, check out the story of hers that I reprinted. First published in Salt Hill, “Stepping Down” is definitely worth a read. You can also learn a lot about writing from her story.

We are here today, however, to take a look at her excellent first novel, You Are Free to Go, a book that won the 2013 Engine Books Novel Prize. (By all means, purchase a copy from the publishing company itself. Amazon is also happy to sell you a copy.)

I had the pleasure of reading the book before its official release, and I was impressed by the skill with which Ms. Yaw created the world of Hardenberg Correctional Facility and how fully she described the lives of those within its walls. Ms. Yaw also takes the next natural step and communicates the meaning Hardenberg has for those who love its inmates. This “intriguing debut” begins with a close focus on Moses, an appropriately named character who is accustomed to the weariness of his long prison journey. Moses, like most other characters in the book, is shaken when fellow inmate Jorge hangs himself, making permanent the absence felt by his daughter, Gina.

As you can tell from that description, You Are Free to Go has a lot of heavy lifting to do. There are a few complicated settings, including the prison and New York City, and characters who simply can’t and won’t interact with each other. (Corrections officers in federal prisons are pretty firm on that no-one-gets-in-or-out-without-permission thing.) As I thought about what I would say about the book, I kept thinking about how Ms. Yaw balanced the big requirements she had at the beginning of the book. She had to:

- Release a ton of exposition about the prison and the people inside. We need to know all about Jorge in order to feel something upon his death. We must also know about the prison hierarchy and Moses’s ambitions and a good deal about how the prison operates.

- Release a good bit of exposition about Gina and her life in New York City. Gina’s doing very well for herself, though she has plenty to work through. She also has the requisite number of acquaintances, some of whom we must learn about.

- Keep us interested in reading further by ameliorating the affect of her exposition drops through the use of scenework.

It can be very hard to know how much “telling” and how much “showing” we can and must do at the beginning of a work. For example, Jorge is not just going to look at Moses and say, “It’s so great that my daughter went to Brown and has an apartment on the Upper East Side.” No, that’s work for Moses to do in league with the third person narrator.

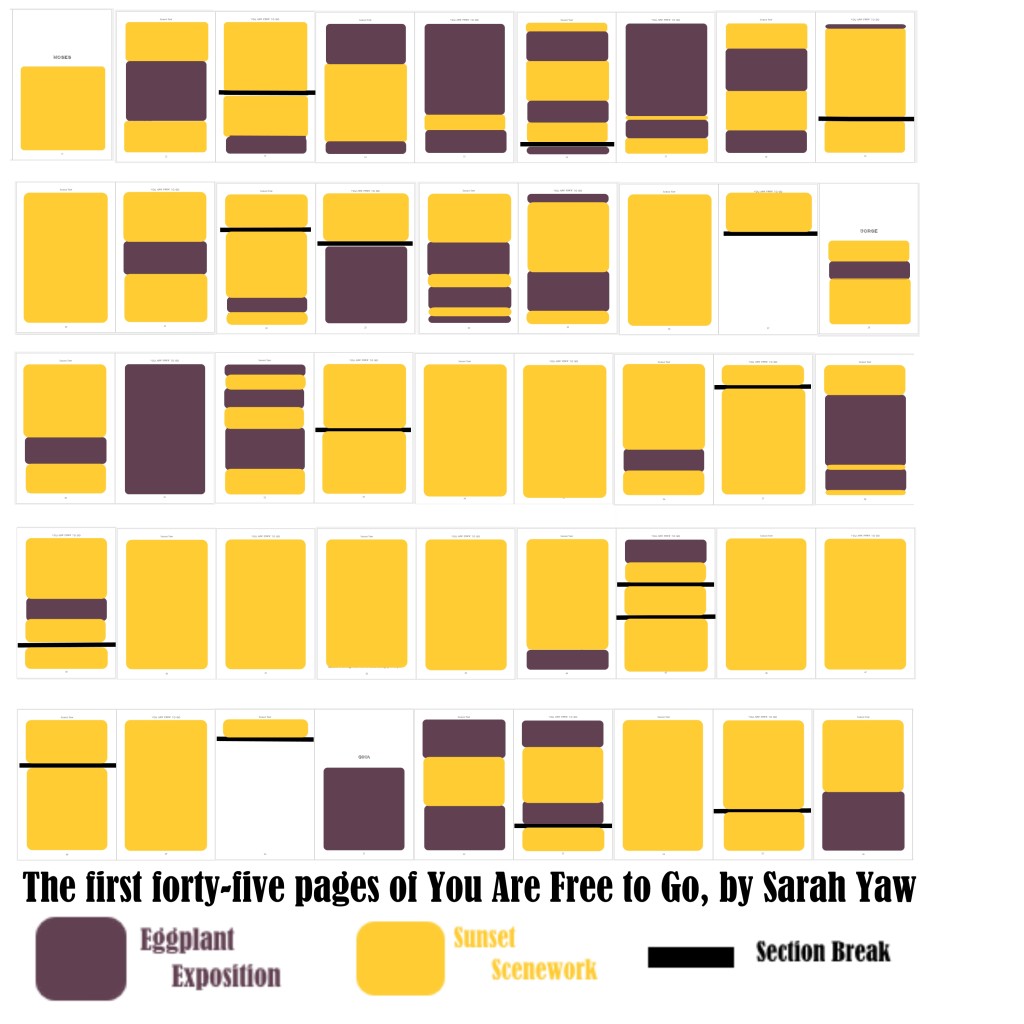

I thought it might be fun to look at the balance between exposition and scene work in a visual manner. In that spirit, I pasted together images of the first 45 pages of You Are Free to Go. The present-tense Scenework is colored in Sunset, and the Exposition is in Eggplant. Take a look:

Isn’t that interesting? Now, there’s always going to be some bleedthrough. Perhaps the narrator released a stray bit of exposition in the middle of a page of dialogue. But what do we notice? How did Ms. Yaw balance the need to tell us things with the need to keep us interested?

- She began the novel in scene. Moses is beginning his day’s work in the mail room. Yes, Ms. Yaw must fill in a lot of information, but instead of TELLING us about Moses, she puts him in contact with Lila and we have some actual drama to care about instead of a great big ball of exposition.

- She drops those big eggplant-colored bombs of exposition (tales from the past, simple explanations) after we already know about Moses and care enough to accept the exposition.

- She makes an interesting turn around page 22. Look how the scenework overwhelms the exposition. One of the scenes is nearly five pages long! All of that is present-tense work that builds the characters and SHOWS us what we need to know about the prison.

- She repeats the formula at the beginning of each chapter. Scenework with a little exposition sprinkled in…then some nice, thick scenes.

I suppose what we can learn from such an exercise is a reinforcement of the oldest writing advice around: show, don’t tell. I guess I sometimes notice a lot of telling in some of the stories I read; perhaps this is why I’ve been wondering if we’re lecturing too much in literary fiction.

The big lesson is to establish your characters as quickly as possible and then let them live their stories.

Here’s an appropriate example. In 1994’s The Shawshank Redemption, writer and director Frank Darabont uses the credit sequence to establish the exposition: ANDY DUFRESNE WAS FALSELY CONVICTED OF KILLING HIS WIFE AND HER LOVER. HE IS GOING TO SHAWSHANK.

With that exposition out of the way, Darabont introduces the other characters: Red, Warden Norton, Byron Hadley, Brooks Hatlen. Darabont is successful enough in his showing, not telling that we care very deeply about what would otherwise be an incredibly boring scene. No one wants to watch prisoners tar the roof of a building for four minutes. But everyone wants to watch Andy Dufresne regain some of his dignity and earn the respect of the others on the tarring crew, some of whom didn’t particularly like him. (There’s an added bonus in that Andy’s facility with numbers springboards the plot.)

After turning the opening of Ms. Yaw’s novel into an art project, I started to wonder what would happen if I did the same thing to one of my own stories. What would the balance look like?

“Houdini’s Knife” is one of the debut titles from Great Writers Steal Press, and I actually think it’s pretty good. (I usually hate my work.) I’m publishing work that I believe will appeal to a wider audience than most literary stuff. (You Are Free to Go is another example; I can picture my father enjoying the book.) Wouldn’t it be nice if we could break out of the writers-writing-for-other-writers doldrums and reclaim the proverbial “woman on the bus?”

You’ll forgive me for offering you a link to the Great Writers Steal Press website: readingisnothomework.wordpress.com/ See? We need to convince more non-writers that reading is not homework.

You may also enjoy the way I’m experimenting with how we market short stories. See what I did for “Houdini’s Knife?” Maybe you pick up a copy. Why not?

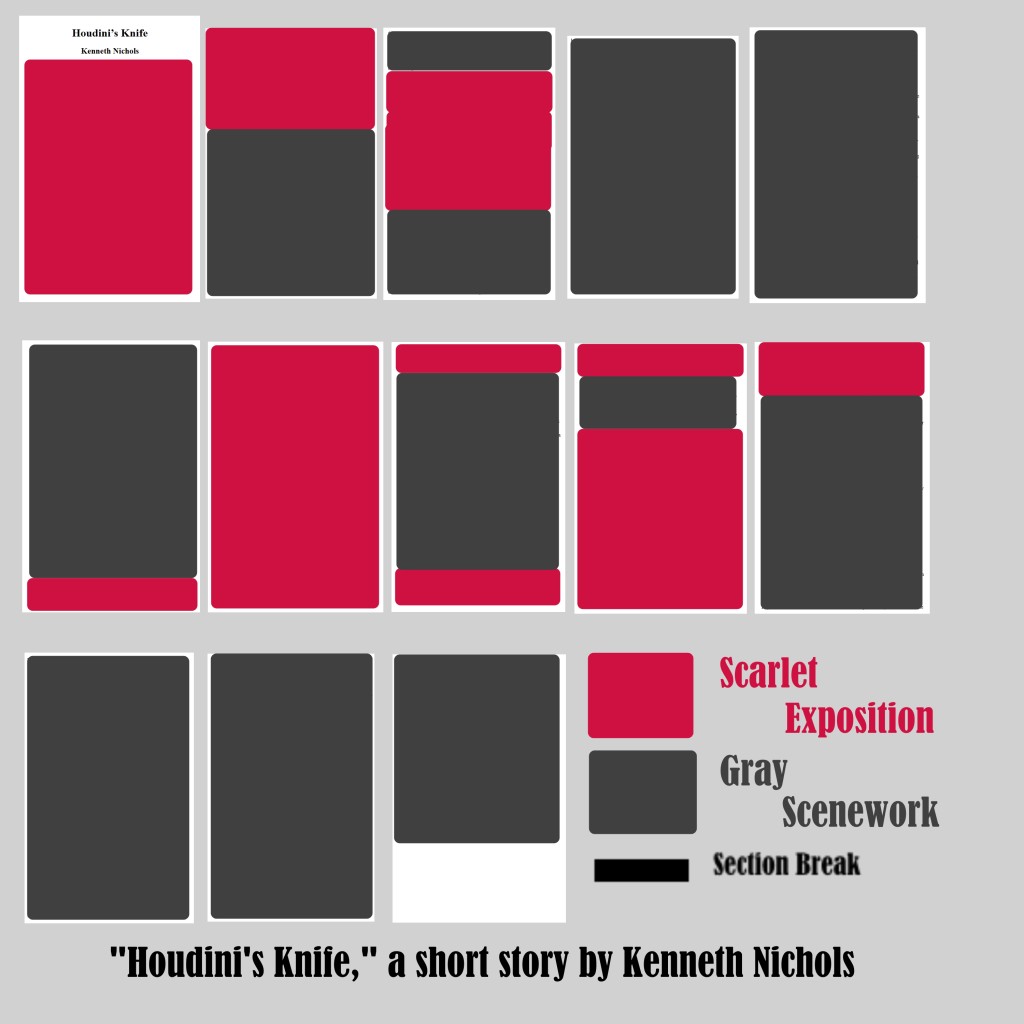

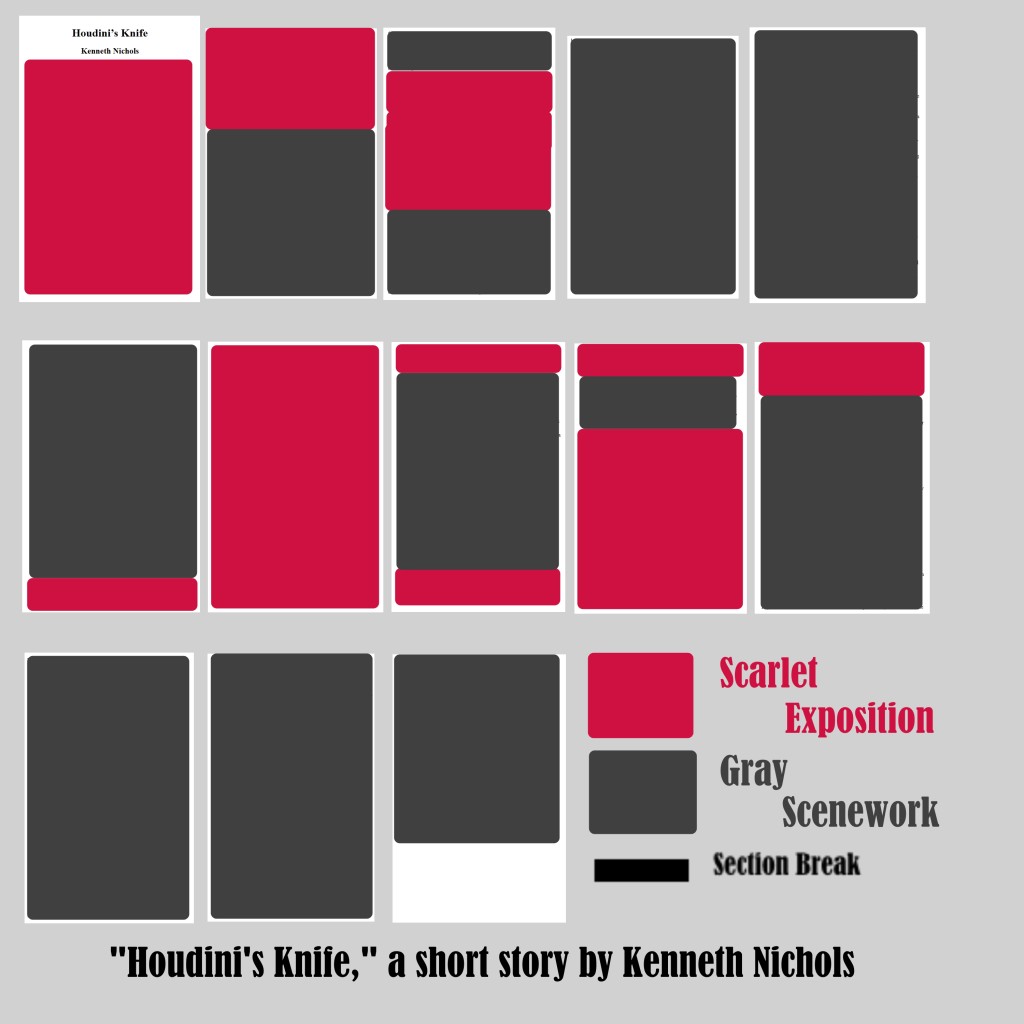

Back to analysis. I gave my story the same treatment as I did You Are Free to Go. In case you didn’t know, I’m a Buckeye. The exposition is in scarlet and the scenework is in gray.

Now, “Houdini’s Knife” was consciously composed as a kind of biography of an eighteen-year-old guy. (I deliberately omitted section breaks in an attempt to keep momentum flowing in the narrative.) The story begins with exposition; I had to reveal that Raymond’s father was a mason. The father died. Raymond was adopted. Raymond got into magic. Raymond has a crush on Becky Brennan. But look!

I did the same thing Ms. Yaw did! I had to tell you a lot about Raymond and his circumstances before I could describe Raymond doing magic tricks. You have to care about Raymond before you care about his chat with Becky Brennan. And once all of that boring exposition is out of the way, I can hit you with the appropriate and compelling ending. (Don’t worry; I don’t usually feel good about anything I write.)

What happens if you give your stories the same treatment? What are some interesting outliers that violate this structure, but are still incredibly compelling? Most of all, isn’t it interesting to think of narrative in a different way?

Reminder: You Are Free to Go is available in all fine independent bookstores, from Barnes and Noble, from Amazon and from Engine Books. You can find more about Sarah Yaw at her website and can say hello to her on Twitter.

Novel

Houdini's Knife, Sarah Yaw, You Are Free to Go

This story first appeared in the Summer 2003 issue of Salt Hill. You can download an attractive PDF of the piece right here. The copyright, of course, remains with Ms. Yaw and GWS is grateful that she allowed the story to be reproduced here. Take a look at what we can steal from the story at this link.

Ms. Yaw’s debut novel, You Are Free to Go, will be published by Engine Books in September 2014. You can visit her site to learn more about the author and her work.

Stepping Down

Sarah Yaw

Those of us who know nothing about prison guards know this: they love loose women and treat their wives like criminals, they never talk about their day unless they’re drinking, they beat prisoners instead of kids and they spend their state wage on boats and cars and pools because a paycheck is for enjoying and God knows they kiss the devil’s ass every day to get one. My best friend Beth, whose father is a guard, says there’s only some truth to it.

Tonight is their game. Lights blast on popcorn-colored and the fans pour in. Not too many—Auburn is a small town docked on a fingery lake in what they all call down there way upstate—but it’s a good turnout for small-town baseball on a rainy night. Tonight I am here for a first date with David who, like everyone else, is here to honor John who was a guard before he was eaten by cancer like a wormy apple. I met David on a boat out on the lake a month ago when I was thinking about other things.

When I met David it was a burning sun and the sky was only as open as the hills. According to Beth, I needed a distraction; I was all but dead. I felt that old. At twenty-eight a divorce is like dentures. And Alex’s leaving had left me geriatric, I’m here with David tonight because he asked, but I am sure now that it is a mistake.

“Karen, a prison guard?” Beth said as we smoked on her porch. “That’s a step down.”

For an August night it is cold from rain that fell a couple hours ago. The sky is closing in on us and the crows are making their way through the northern and western skies for their perching along the dark waters of the Owasco River. David has gone off to the concession for dollar drafts. A mentally retarded boy is behind me in brand-new jeans and a new windbreaker and a new baseball hat and he is waving a triangled banner that screams Double Days in blue and yellow as if this were the big time. There is a counselor, a small pasty-faced brown-haired girl with no-nonsense shoes. Someone is fiddling with the back of my hair. It’s flipped and flipped and flipped again and the counselor says, “No Jason, no. Jason, stop that.” I turn around, and Jason holds his twisted fist to his mouth and smiles a naughty smile and she’s apologizing, but I’m not upset I tell her. “It’s perfectly okay.” I say.

***

The tumbling of weather systems overhead doesn’t look good for the game but the rain at least is holding. David is tall and wide. His hair is short and dark now but he looks as though he must have been a flossy-headed baby. He wears small fashionable wire-rimmed glasses and is surprisingly handsome, though not my type, He sits down next to me and hands me a beer and we watch boys in blue shirts push large janitorial brooms in unison as if it were a show. They wipe away water from the tarps that cover the well-kept sod. They even play special sweeping music. The team’s blue boys sweep the entire infield expertly in one pass. When they’re done, they are in a perfect line and in time with the music they all hold the brooms away from their chests with their left arms looking like the final formation in a chorus number. Taking their positions along the tarp’s edge, they roll ably in hopes of bringing the players to the field before the clouds boiling overhead erupt and send us all home. I am entertained but David says he wants the game to start so John’s son Daren can toss the first pitch. The newspaper is here waiting to click and flash a picture and everyone is waiting to remember in silence the man who died not as he died with rickety ribs and a mouth nearly glued shut with thirst, but as the young man we can all admire now that he is dead and above reproach.

David points out John’s wife across the stands. I am jealous of her because my memories of Alex are not so unadulterated. Alex left quickly and at Christmas time.

“Is this your first time to a game?” David asks.

“As an adult,” I say.

“Well things have changed a little I imagine,” he says looking around at the stands. And they have. This is a new stadium, an imitation of an old ballpark.

“Yup, everything,” I say as music turns up turning this into a waiting-to-play party. The guards are gathering in loud standing groups and the wives are seated wrapped in fleece blankets and the children are running in splashy swarms through the stands.

“What?” he says.

“Everything has changed,” I say. He nods in agreement with a story he doesn’t know and sits silently looking out across the misty field. David, I have noticed, widens his gray, blue, green eyes when I’m speaking like he’s listening with them. He repeats what I’ve said and adds little. In my estimation he must not be very smart.

“I guess this is nothing like New York. I bet you miss it,” he says.

“I miss the food and the movies,” I say.

“Food and movies—Auburn’s not so fun after all that.” He leans back and crosses his legs. He leans his elbows on the seats behind him and his chest is broad.

“I missed the lakes when I lived away,” he says.

“Where were you?” I am shocked he’s been anywhere but here.

“Where was I? Tucson. For a girl,” he laughs. “And then she kicked me out so her boyfriend could move in and I came home to my mother’s house. Like you,” he says. “But I lived in the basement.”

I laugh because Beth said on first dates you need to act amused by what they say even if you’re not. And I am not because I am thinking of the day my father came to Brooklyn to bring me home and how my stomach turned and I tasted failure like I had lost the war, like I was retreating and leaving behind spoils. I hate that David thinks he’s anything like me. That he thinks he knows anything about my life.

I do live in my mother’s house—in an apartment above the library in her enormous house. I cook my own meals there and smoke late at night to forget that I used to have plans. But I am nothing like him, I assure myself. At one time my life had weight, it had purpose, it was big and I knew exactly how to be in it. Now, instead of dinner parties and brunching at a long table of coupled-up friends, or a job with children, I exercise and lunch with ladies who take tremendous pity on me and stroke my head. I don’t work. I eat sushi with them and listen to their endless advice: exercise, read books, listen to tapes, write in your journal, take long kind baths. It will all be okay. You’ll meet someone, they say as if it is the sad and inevitable truth. Being single doesn’t last forever, just hope it’s a good one next time, they say this as if we have no control in our desperation over who comes and who goes and who stays. Besides, you’re pretty enough they say. Blondes don’t stay single.

But I am fair and forgettable. Just like I’ve always been fair and forgettable, like I am in the pictures that line the walls of my mother’s house. The pictures of the know-it-all girl. The predictable and cautious girl. The girl who knew just how things would turn out. When I walk through the dark house on nights when I can’t find Alex I look at her and I miss her.

Beth tells me, “It’s okay to just hide out for a while, but sooner or later you’ve got to get back out there.” That’s why I’m here tonight, not because of any great hopes, but because I am taking her advice like I take the ladies’ advice. I listen to everyone who has ever been alone and I wonder how it is they are all still standing.

***

I smell David as he leans next to me to reach to the ground to pick up his keys that have fallen from his pocket and I know that he is not for me. He smells funny like laundry and soap and there is the smell that is all his and it scares me. He is not right. He is too tall, too thin, too unfamiliar.

Alex who is a musician and who is pretty much always afraid of death and who wakes in the night gripping his chest drenched in sweat from fear is exactly what I’m used to. David who spends his days unarmed, locked in a prison with murderers doing who knows what, who sits next to me straight and still and looks me in the eye without feeling the need to speak while slowly sipping his beer is unacceptable because I crave Alex. I crave him all the time. At night in my dreams we still sleep against another and it’s as if nothing has changed, as if the next thing known will be our waking up on old age as the arm-in-arm couple walking the side-by-side, no-particular-place-to-go-walk. All my will be understood again. Clear. Expected. Guaranteed.

Looking at John’s wife across the stands with her simple brown hair and an old sweatshirt and jeans and white sneakers sitting with her feet wedged on the railing in front of her, knees to her chin and her arm around her boy as she stares into the lights, caught in their greasy smear, I envy her more and more her mourning.

***

French Fries! French Fries! French Fries! yells Jason the retarded boy as he rushes the concessions and tosses his blue Double Days banner to the ground in his dash out of the stands. David makes a big deal about picking it up and presenting it to me as a gift. It makes me uncomfortable and I smile tensely and tell him that it, the banner, reminds me of when I was a teacher. “I taught Kindergarten in a private day school and what l loved most was teaching my students about the shape of things.” I look at the banner. “’Everywhere you can find a triangle, an ellipse, a trapezoid,’ I used to tell them. ‘The world is easier to understand when you can fit it into a cube,’ I always said.”

“You can fit it into a cube? You really believe that?” he asks.

“Well,” I say, shocked. “It helped them learn the shapes. Besides, they need to know how things work. You’re in a prison all day, wouldn’t it be better if everyone played by the rules?”

“Yeah, it would,” he says. “But life doesn’t go like that, you know that by now.” We’re quiet for a moment. I am looking away when he places his hand on the middle of my back and says apologetically, “Go on with your story.” I don’t want to because I am angry that he won’t just sit there amused by me. Who the hell is he, anyway?

Beth did say, “You never know, maybe he’s different, maybe he’ll surprise you.”

“Go on,” he says.

“Well.” I am afraid to tell him how my room was alphabetized, hierarchical, gradated, and clean. “I had glistening evaluations. The students excelled. The parents were always satisfied. The end.”

“Did you quit your job when you came home?”

“Yes,” I lie. The truth is I was fired, but he doesn’t need to know that. Or how my boss told me they were moving towards a more open approach to learning and, in her opinion, I had no knack for it. Or that that was the precise moment when everything changed.

***

Tonight there is always the weather. There is rumbling deeper in the distance. But it is in the North and seems to be far from town. The boys in blue shirts are sweeping the bases and putting down the lines. The gray clouds tumble as though they are amused. The wind is ripping through the trees tossing the crows this way and that and has brought with it the smell of manure. 1t’s from the northern farms that roll flatly out from Canada and like a mantle it covers us.

If I were from somewhere else, I think, a place where it was not known what form love sometimes takes I would never wager on the attraction of opposites. Tonight, the women are shivering in the stands and the men are drinking and they are all not talking. Not with each other, anyway. The women huddle. They complain. They yell, periodically, at their buzzing children. Sometimes they swear. “Fuck this cold in August,” one yells from under a blanket. They never ever look to where their husbands are standing right behind home plate yelling to David to get the hell over here. They laugh because this is a date, make a big deal about how they are going to steal him away. And I am mortified because I am someone’s wife.

Beth said, “Expect a lot of stories about Jewish pedophiles, Nigger kid killers and just plain old white perverts. That is what my father talks about when he drinks.” And David is absorbed into a conversation in which hands are flying and I am imagining the worst sorts of stories.

I sit alone and search for something to consume from my memory of Alex. I look for a last secret sweet kept willfully locked away in my chest. I sift through the bones that are still pure, but I can’t find any.

It was not long after I lost my job that Alex pulled away from me and snapped, He primped. He did sit ups. At dinner with friends he wouldn’t sit. Instead he ate standing as if edging towards the door. We don’t even have sex, he said on Halloween. I am unhappy, he said one month later. Everyday I spend with you makes me feel one day closer to death, he said for Christmas gripping his chest in a midnight sweat. Then he left.

John’s wife is also alone and I wonder why it is the ladies haven’t flocked to her.

I envy her still. Every morning Alex wakes up. Every morning in a small attic apartment in Brooklyn, three blocks from ours, he wakes up with his arm asleep under the head of some other woman. I look up and see David. His flirting eye is on me as the men keep him locked up and I can see he wants out, he’s had enough of their talk; he wants to come back and from here I can see Alex never will.

Jason grabs the back of my shirt and it cuts me in the neck. I laugh but David who has just come back does not. David handles it. He turns to Jason and says, “Hey, buddy, give me five.” It works. Jason laughs and slaps David’s hand over and over and over. It turns out David knows the counselor. They chit and they chat about the intrepid game. David takes my hand and l let him. With it he points Jason’s attention to the sky. Jason makes eerie, Halloween house OOOOOOOOS when he sees the blackness of it. The counselor leans into David and whispers not too quietly that these clouds are proof that there is a God, “That guy was a cheatin’ bastard,” she says about John. “Everybody knows it too,” she says loudly. And I understand why John’s wife is alone and why none of the other wives want to be near her.

The boys in blue shirts roll out the tarp again. “Canceled!” Everyone yells. A loud and angry, “Ahhhh!” explodes from the men, “I told you so,” “I knew it,” they claim. “On John’s day. What a shame. What a Goddamned shame.” The women Thank Freaking God that they get to go home.

I see David looking over at John’s wife. He is silent but not still. He has taken my hand and wrapped it in his and placed it in his lap and he is huddling over it and tapping each of his legs and says in a terse voice that he’s glad it’s canceled, for her sake. I agree and we watch as she grabs her things and hurries her disappointed boy out of the stadium.

Sarah Yaw’s novel The Other Side of the Wall was recently selected by Robin Black as the winner of the 2013 Engine Books Novel Prize. Sarah received an MFA in Fiction from Sarah Lawrence College and is an Assistant Professor at Cayuga Community College, where she does all kinds of cool things. She lives in Auburn, NY with her four-year-old twins, her husband, the photographer Douglas Lloyd, a fish named John, and a couple of neglected houseplants that are doing a lousy job filling the void left by two old, beloved dogs.

Short Story

2003, Sarah Yaw, Stepping Down

Title of Work and its Form: “Stepping Down,” short story

Author: Sarah Yaw

Date of Work: 2003

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story made its debut in the Summer 2003 issue of Salt Hill, a very cool journal. Ms. Yaw has been kind enough to let me republish the story. You will find the story in plain text format here. You can also download a PDF of the story here. Her novel The Other Side of the Wall was recently selected by Robin Black as the winner of the 2013 Engine Books Novel Prize. The book will be released in September 2014 and is definitely worth your time. You can learn more about the book and its author at sarahyaw.com.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Place

Discussion:

Karen’s life is not going the way she thought it would. She moved away from her beloved New York City and now lives with her mother. She’s a divorcee and is on a date with a prison guard, one of many who populate Auburn, New York, “a small town docked on a fingery lake in what they call down there way upstate.” David is a good enough guy, but it seems that Karen is not ready for a relationship. She’s fresh out of a divorce and a bit adrift in her life, an existence that Karen believes once had weight and purpose, but is now being wasted. A storm is rolling into Auburn, spoiling the ballgame and the fundraiser that is being held for John, a prison guard “who was a guard before he was eaten by cancer like a wormy apple.” When we last see Karen, she is filled with envy and sublimated sadness. Still, there’s the sense that Karen will manage to get some air in her sails and move on.

The reader (at least this one) is struck most by Ms. Yaw’s use of place. The title itself is a reference to place. Karen is “stepping down” from Brooklyn to Central New York. Auburn is a very important part of the story; in a way, the piece could not have taken anywhere else. To whom do we look when we consider the purpose and meaning of place in fiction? Why, Eudora Welty, of course:

It is by the nature of itself that fiction is all bound up in the local. The internal reason for that is surely that feelings are bound up in place. The human mind is a mass of associations more poetic even than actual. I say, “The Yorkshire Moors,” and you will say, “Wuthering Heights,” and I have only to murmur, “If Father were only alive-” for you to come back with “We could go to Moscow,” which certainly is not even so. The truth is, fiction depends for its life on place. Location is the crossroads of circumstance, the proving ground of “What happened? Who’s here? Who’s coming?” - and that is the heart’s field.

Auburn is the crossroads of the circumstances depicted in “Stepping Down.” That town is the only place on Earth where all of the elements can be found: lonely Karen figuring out her life, David the prison guard easing into his own existence, John’s widow, the storm that cancels the fundraiser. In a marvelous way, everything that has ever happened in the history of the universe has converged so that the story can happen the way it does.

Look at what else Ms. Welty says:

Feelings are bound up in place, and in art, from time to time, place undoubtedly works upon genius.

Think about your hometown. There’s the supermarket where you had your first job and suffered the first indignities of your professional life. There’s the wooded area where you kissed your first crush. The childhood home that served as a crucible for your hopes and fears. Ms. Yaw and Ms. Welty understand that a story is not an isolated incident that takes place in a vacuum. Their characters (and yours) have a history, just as the streets where you grew up have been traveled by countless people: some good, some bad. Lovers and fighters. Young and old and everything in between. Understanding the meaning of place in your work can add a sense of continuity that lends it weight.

Look at Ms. Yaw’s second paragraph:

Tonight is their game. Lights blast on popcorn-colored and the fans pour in. Not too many—Auburn is a small town docked on a fingery lake in what they all call down there way upstate—but it’s a good turnout for small-town baseball on a rainy night. Tonight I am here for a first date with David who, like everyone else, is here to honor John who was a guard before he was eaten by cancer like a wormy apple. I met David on a boat out on the lake a month ago when I was thinking about other things.

Ms. Yaw does a lot in this paragraph. There’s a lot of exposition and graceful description of what the town is like. The reader learns about the protagonist and her date. (The antagonist of the piece?) Most importantly, Ms. Yaw gives Karen an important reason to be at the game, outside of the pedestrian fact that she’s on a date. The game is a benefit for the dearly departed John. This element of the story, laid so early, also lends an internal logic to the end of the story. The benefit is rained out and David looks at the widow John perhaps wondering if he and Karen will end up married.

By making this move, Ms. Yaw ensures that the reader doesn’t see HER hands as those who shape the plot of the story. Yes, Ms. Yaw was sitting at her typewriter or in front of a notebook and was the one who literally ended the date and brought in the rain. In the story, however, everything happens as a result of the actions of the characters. (Um…except for the rain. But you get the point.)

Let’s also take note with regard to Ms. Yaw’s contribution to the eternal struggle: HOW SHOULD WE USE WHITE SPACE? The story takes place in real time, but is broken up four times by white space. I don’t believe that the breaks are motivated by the need to advance in time; it seems as though Ms. Yaw uses the breaks as an opportunity for emotional closure or catharsis. How appropriate! Karen is a character who is defined (in this piece) by her need to understand herself; the pauses Ms. Yaw literally puts on the page offer readers the same opportunity.

What Should We Steal?

- Set your stories in real, authentic places. Your characters should inhabit real cities and towns that exist in a larger world. People can’t live in a vacuum…neither can characters.

- Imbue your work with an internal logic. A story should not seem as though its events are being put in action by the invisible hand of the author. Instead, it should seem as though they are acting of their own accord.

- WHITE SPACE USE #24601: Break up the narrative with white space in order to offer the reader and/or your characters time to appreciate the emotions that are developing in the story.

Short Story

2003, Claudia Zuluaga, GWS Reprint, Place, Salt Hill, Sarah Lawrence, Sarah Yaw