David Callow is exactly the kind of person I love to hate. There’s absolutely nothing special about him. He doesn’t sing. He doesn’t dance. He has no talent aside from waking up and clicking “record” with his cell phone.

But that doesn’t stop him from being a global media superstar. Continue Reading

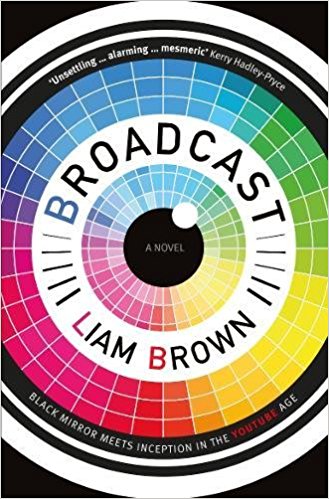

Novel

Liam Brown, Science Fiction

First things first. I hate when you can’t find the table of contents for an anthology. So here it is, with an assist from editor Jonathan Strahan. I’ve organized the stories in Volume 11 of The Best Science Fiction and Fantasy of the Year in order of appearance.

Introduction, Jonathan Strahan

“The Future is Blue”, Catherynne M Valente (Drowned Worlds)

“Spinning Silver”, Naomi Novik (The Starlit Wood)

“Mika Model”, Paolo Bacigalupi (Slate)

“Two’s Company”, Joe Abercrombie (Sharp Ends)

“You Make Pattaya”, Rich Larson (Interzone 247)

“You’ll Surely Drown Here If You Stay “, Alyssa Wong (Uncanny 10, 5-6/16)

“A Salvaging of Ghosts”, Aliette de Bodard (Beneath Ceaseless Skies, 01/03/16)

“Even the Crumbs Were Delicious”, Daryl Gregory (The Starlit Wood)

“Number Nine Moon”, Alex Irvine (F&SF, 1/16)

“Things with Beards”, Sam J Miller (Clarkesworld 117, 6/16)

“Successor, Usurper, Replacement”, Alice Sola Kim (Buzzfeed, 10/26/16)

“Laws of Night and Silk”, Seth Dickinson (Beneath Ceaseless Skies, 26 May 2016)

“Touring with the Alien”, Carolyn Ives Gilman (Clarkesworld 115, 4/16)

“The Great Detective”, Delia Sherman (Tor.com)

“Everyone from Themis Sends Letters Home”, Genevieve Valentine (Clarkesworld)

“Those Shadows Laugh”, Geoff Ryman (F&SF, 9-10/16)

“Seasons of Glass and Iron”, Amal El-Mohtar (The Starlit wood)

“The Art of Space Travel”, Nina Allan (Tor.com)

“Whisper Road (Murder Ballad No. 9)”, Caitlín R. Kiernan (Sirenia Digest 125, 7/16)

“Red Dirt Witch”, N.K. Jemisin (Fantasy/PoC Destroy Fantasy)

“Red as Blood and White as Bone”, Theodora Goss (Tor.com)

“Terminal”, Lavie Tidhar (Tor.com, 04/16)

“Foxfire Foxfire”, Yoon Ha Lee (Beneath Ceaseless Skies, March 2016)

“Elves of Antarctica”, Paul McAuley (Drowned Worlds)

“The Witch of Orion Waste and the Boy Knight”, E Lily Yu (Uncanny 12)

“Seven Birthdays”, Ken Liu (Bridging Infinity)

“The Visitor from Taured”, Ian R. MacLeod (Asimov’s, 9/16)

“Fable”, Charles Yu (The New Yorker, 5/30/16)

As Mr. Strahan points out in his introduction-and don’t you love the introductions to best-of volumes?-science fiction and fantasy are fields in the midst of a great number of changes. Science fiction was one of my early loves. I started very early with Asimov and Ellison and Bradbury and other giants of the genre and loved Asimov’s and Analog and F&SF. I loved the way that ideas drive the field. Great SF is all about the truly extreme WHAT IFs.

What if the Axis won WWII and each took possession of half of the United States? (Dick’s The Man in the High Castle.)

What if there were a medical procedure that could make you and your husband young again; you both undergo the procedure, but it only works on your spouse? (Sawyer’s Rollback.)

What if a little kid general were Earth’s only hope against hostile aliens? (Card’s Ender’s Game.)

Everything changes, unfortunately. (I don’t like change.) Over the past twenty years, it seems to me, science fiction and fantasy have evolved in the same direction as literary fiction. Less focus on plot, more focus on atmosphere. More emphasis on playing with language. Keeping the reader by inviting them to resolve the abstract.

There are, of course, many ways to tell a story and Mr. Strahan presents a volume of work that engages a wide range of protagonists, settings and ideas. I thought it would be interesting to compare two of my favorites to demonstrate how we can take different routes to the same destination.

Rich Larson’s “You Make Pattaya” announces itself in an interesting manner and establishes character, setting and tone in a felicitous manner. Let’s take a look at the first paragraph:

Dorian sprawled back on sweaty sheets, watching Nan, or Nahm, or whatever her name was, grind up against the mirror, beaming at the pop star projected there like she’d never seen smartglass before. He knew she was from some rural eastern province; she’d babbled as much to him while he crushed and wrapped parachutes for their first round of party polls. But after a year in Pattaya, you’d think she would have lost the big eyes and the bubbliness. Both of which were starting to massively grate on him.

What do we learn immediately and what do we love?

- There’s sex going on. Many people like reading about that sort of thing. (Subject matter)

- This is science fiction. There’s some kind of TV show playing in the mirror. (Genre)

- Nan or Nahm is a rural girl in the big city. She must be relatively poor and probably has found a lot of ways to make money, regardless of whether or not she’s being exploited. (Theme)

- Pattaya. City in Thailand. Where there’s lots of water and therefore lots of boats. A place where, as I understand it from Law & Order: SVU, there are slightly different attitudes about the connection between sex and money. (Setting.)

- Her bubbliness “grates” on him. Dorian isn’t the world’s sweetest guy. (Characterization.)

Mr. Larson gets the narrative off and running very quickly and packs all of the elements of our writers’ toolbox into as few sentences as possible. The story speeds along nicely, while still allowing the reader to enjoy the setting and the technology.

I don’t want to give away too much of the story, so I’ll be circumspect. It’s clear that Dorian feels great lust for Nahm. He also understands how hard she has worked to provide for herself; he’s a scammer, too. (He skims personal information from the unprotected devices tourists carry around.) The story takes place over a short period of time and drops the characters into a taut, compelling plot: Dorian and Nahm are going to team up and engage in a lucrative caper. (Capers are so much fun! Things happen! There are big stakes!

I also admired that Dorian and Nahm are not pushed into straitjackets and forced to act according to their…”demographics.” Sure, Nahm’s English is accented. That makes sense. But accents don’t mean as much about a person as their actions, right? Instead of writing Nahm to be a cartoonish virtuous victim of circumstance and economics, Mr. Larson allows her to be good and bad. Just like real human beings.

Ian R. MacLeod’s “The Visitor From Taured” is an interesting counterpart to the Larson story. A character named Lita tells the story, split into a number of different sections. Lita’s tale takes place over the course of several decades and is really about her relationship with Rob Holm, a handsome rogue who devoted his life to astrophysics. Lita, you see, is one of the rare old-fashioned people who goes to college to learn about those archaic, non-interactive narratives that people called “books.”

This story is not a whiz-bang caper. The narrative covers a massive amount of time in only twenty-four pages and a lot less actual stuff happens. Now, this is not necessarily a bad thing. If the plot is not as big and flashy, the author must simply make sure that he or she offers the reader something else in return. How did Mr. MacLeod keep my attention, even though there wasn’t as much plot as a Star Wars movie?

- Lots of book and English grad student talk. I guess this won’t work for everyone, but it did work for me because I could relate so well.

- Romance! We all love romance. Lita tells us very early in the story how handsome and temperamental Rob is. My study of Hugh Grant movies has convinced me that is the magic combination to win over the ladies.

- Seeds are planted and allowed to grow. Humans love beginnings, middles, and ends. Lita convinces Rob to try reading one of those confusing paper-based books. He soon likes books. His tastes evolve and change. Literature becomes a way for them to relate. See how this development can keep the reader’s attention?

- Consummation. It’s pretty clear how Lita feels about Rob-and why she’s telling us the story in the first place. It’s altogether fitting and proper that she and he come together.

These two stories are, in a way, romance stories, but they’re helpful to us because of their differences. We can take our time with a narrative or we can zoom along, but we must always serve our specific characters and plot in a manner that will keep the audience’s attention.

Mr. Strahan has assembled a diverse roster of stories and seems to have taken great pains to search beyond the Big Three magazines. I’ve always thought of the O. Henry collections of literary short stories as the literary, experimental cousins of the slightly more staid Best American series. Perhaps Mr. Strahan’s collections are where you can turn when you are more in the mood for poeticism than plot or in a time when you have a hungrier heart than mind.

Anthology

Fantasy, Jonathan Strahan, Science Fiction

C Stuart Hardwick‘s “Dreams of the Rocket Man” tells the story of Jimmy, a man who looks back on his youth and his relationship with Mr. Coanda, an older gent who enjoyed building rockets. The story appeared in the September 2016 issue of Analog: Science Fiction and Fact, one of the top three SF/F magazines out there. Mr. Hardwick is kind enough to offer the story on his web site; check it out!

The piece is an interesting example of a story whose narrator looks back and skips through time like a stone on the surface of a lake. By design, these kinds of stories don’t spend much time in any one scene and don’t delve particularly deeply into any one moment. Lots of work is structured in this manner; one of these is my short story, “Masher Doyle.” Unfortunately, no one has ever read that one. Here are some real examples:

That’s all I can think of at the moment. (Feel free to add other suggestions in the comments!)

What Mr. Hardwick loses in depth of scene by employing this structure, he makes up for in the scope of his story. By taking a look from a distance and zooming along to focus on the important bits, the author is able to chronicle a wide swath of Jimmy’s life.

Come to think of it, a lot of Stanley Kubrick’s work operates in the same kind of way. The “narrator” of The Shining takes a long-distance look at the Torrance family’s fateful winter and skips along to feature the important bits.

The “narrator” of Full Metal Jacket takes a long-distance look at Private Joker’s Vietnam experience and skips along to feature the important bits.

The “narrator” of 2001: A Space Odyssey takes a long-distance look at humanity’s relationship with the universe and skips along to feature the important bits.

The “narrator” of A.I.: Artificial Intelligence (developed by Kubrick, though directed by Spielberg) takes a long-distance look at David’s life over the millenia and skips along to feature the important bits.

(Hmm…I’ll bet someone has written a paper about Kubrick and narrative structure.)

The protagonist is a young man (then a grown man) who loves rocketry. As a result, Mr. Hardwick has a duty to depict this love in a realistic way. The story must have verisimilitude: the appearance of reality in fiction. Mr. Coanda and Jimmy must sound as though they know a lot about rocketry or readers might bail, having had the magic spell broken. Let’s look at how Mr. Hardwick handles some of the “smart person rocket stuff.”

He said that in space travel, the cost of a launch is determined by all kinds of things, not just the weight of machinery, fuel, and oxidizer, but also the aerodynamics and trajectory which control how much air resistance and gravity a rocket must fight before it reaches orbit.

I knew all that stuff! The sentence is also a nice summary of some of the most important basic principles of rocketry.

As it staged and staged again, the ground slowly warped into a fisheye ball. When the propellant finally ran out, the Earth was just an azure band beneath the inky black of space.

Mr. Coanda let a handful of popcorn fall back into the bowl. “Holy hell,” he said, “if that ain’t a beautiful sight.”

I was similarly entranced. “How high do you figure we went?”

“I don’t have to figure. I have data. Ah…63,000 feet.”

“Wow! That’s almost in space!”

“Not quite. Minimum orbit’s eight times higher, and then you have to accelerate to orbital velocity in order to stay there.”

I stared at the glowing earthscape. “Still…”

Isn’t the “azure band” part pretty? I love how this bit evokes the kind of awe that we should all have for this kind of science and the author also reinforces that Mr. Coanda knows his stuff and that little Jimmy is very bright, but still learning. The part about the orbit and orbital velocity isn’t totally necessary, but it adds credence to the characters and their milieu.

“And it works terrific,” he said, “It’ll never produce enough LOX to do the whole job alone, but that’s another trade-off. If it can do much better than pay its own way, then–“

Lox? Is Mr. Hardwick trying to get us hungry for breakfast? No, he means “liquid oxygen.” As an enthusiast of Gemini/Mercury/Apollo-era spaceflight, I knew the character didn’t mean salmon. You’ll also note that Mr. Hardwick includes the phrase “liquid oxygen” to give the reader a hint, but it’s not wholly necessary. If the reader doesn’t know the terms, they will just gloss over them while understanding that the characters know what they’re talking about.

I could never, ever pass a calculus class and Dr. William Widnall loses me when he talks about smart people stuff, but he, like Mr. Hardwick, convince me that they know what they’re talking about.

SPOILER ALERT! Just read the piece if you didn’t. Here are the last few sentences of the piece:

I’ve run the camp now for longer than I worked in engineering, but to these kids and the world, I’ll always be the Rocket Man, a mythological hero from a golden age. And that’s fine by me. I’ll proudly wear that title while I fan the flames, till the next bearer comes along to change up the world behind me. It’s not the adventure I imagined for my life, but you never quite know where dreams will lead.

Okay, so Mr. Hardwick is in the same place I was when I wrote “Masher Doyle.” We both told the narrator’s story from childhood to adulthood. Both of us wrote about mentor figures who helped our narrators build themselves up from childhood problems. So what to do with the conclusion of the story?

The last paragraph can be your opportunity to unspool poetry for poetry’s sake. The storytelling is largely over, so why not tip the scales in favor of aesthetic beauty over plot?

Short Story

Analog, C Stuart Hardwick, Science Fiction

Title of Work and its Form: I. Asimov, memoir

Author: Isaac Asimov

Date of Work: 1994

Where the Work Can Be Found: The book can be found in countless independent bookstores across the country or even on those great big megawebsites that don’t need your money quite as much.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Narrative Structure

Discussion:

Ken’s note: This post is going live on January 2, 2013, which would have been Isaac’s 93rd birthday. Although the Good Doctor is gone, here’s hoping that his countless fans take this opportunity to celebrate his memory and his massive body of work.

Who knows why, but Isaac Asimov is one of the first few authors with whom I fell in love. I was in awe of the fact that he published such a wide range of books…and so many of them! Science fiction was one of my first loves; Asimov was one of the Big Three and even had a magazine named after him. I remember reading my first copy of I. Asimov to tatters even though, as Asimov admitted, his life was not the most exciting ever.

I. Asimov is the man’s third autobiography. In Memory Yet Green and In Joy Still Felt are thick monsters that recount the entertaining minutiae of Asimov’s life through the late 1970s. With a decade having passed (and illness clearly becoming more of a concern), Asimov acceded to those who insisted that he fill in the remaining blanks of his life story. In his introduction, Asimov describes the book’s form:

So what I intend to do is describe my whole life as a way of presenting my thoughts and make it an independent autobiography standing on its own feet. I won’t go into the kind of detail I went into the first two volumes. What I intend to do is to break the book into numerous sections, each dealing with some different phase of my life or some different person who affected me, and follow it as far as necessary-to the very present, if need be.

Instead of following a strict chronology and describing the life as it was lived, Asimov presents 166 vignettes of varying length. Sure, the first few stories are about his upbringing and his parents, but isn’t this a logical place to start for anyone seeking to tell their story? It’s also fitting that the last few vignettes describe his struggle to remain healthy and to work in the face of increasing infirmity. (The illness was far worse than the public understood, of course. Asimov had contracted AIDS from a blood transfusion during a 1983 heart bypass operation.)

What are we, Asimov suggests with his structure, but the sum of the people we have loved and the passions we have fostered? In the 90th section, Asimov describes how much he loves the busywork of creating indexes for his books. In the 104th section, he pays tribute to Judy-Lynn del Rey, a friend who died very young. A hundred pages later, he recounts the vacations he took at a favorite resort and how he came to have a science fiction magazine named for him.

I. Asimov benefits from the variety granted by the book’s form. If you don’t want to read about the fear of travel that kept Asimov largely bound to the Northeast, no worries. Just skip a few pages and read about his friendship with Hugh Downs. Not interested in Hugh Downs? Turn the page and read about how it felt to discover one of his books had become a best-seller.

The book takes on a stream-of-consciousness feel because of its structure. In a way, you feel as though you are sitting down with Isaac, having a beer. (Well, he would have a coffee or something because he was a teetotaler for most of his life.) If you could still chat up Asimov, he would only tell you the parts of his life that he felt were most interesting, an effect that is maintained in the book.

What Should We Steal?

- Consider the use of connected vignettes to eliminate dead weight. Have you ever been trapped at a party with the most boringest guy in the world? You ask him about his day, and he says, “Well, I woke up and I needed to get out of bed so I rotated my body ninety degrees and put my feet on the floor. But I did so slowly because I wasn’t sure how cold the floor was. But the floor wasn’t cold. I put my full weight on my feet and walked to the bathroom, alternating steps between my right foot and my left foot. I had to take a shower, so I started the water, making sure there I turned the left-hand spigot to make the water warm enough…” Vignettes let you get to the important part!

- Consider the use of connected vignettes to simulate the feel of a conversation. Let’s say you could have dinner with Thomas Jefferson. You would want TJ to do the same thing Asimov did: tell you interesting stories that span the whole of his lifetime. Not only would he focus on some of the more interesting stories, but you would also gain insight into the man’s mind based upon what he tells you and when.

Creative Nonfiction

1994, Isaac Asimov, Narrative Structure, Science Fiction