Title of Work and its Form: “Miss Lora,” short story

Author: Junot Diaz

Date of Work: 2012

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story debuted in the April 23, 2012 issue of The New Yorker. As of this writing, the story is available for free on the New Yorker web site. You will also find the story in his collection This is How You Lose Her. You will also find the story in the 2013 edition of Best American Short Stories.

Bonuses: Very cool! The Brooklyn Academy of Music commissioned Nathan Gelgud to adapt “Miss Lora” into the form of the graphic novel. You can view it here. Writer and critic Charles May shares some thoughts about “Miss Lora.” You may or may not agree with them, but you should enjoy the discussion. Here are my thoughts about the Junot Diaz story, “Alma.”

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Exposition

Discussion:

You are a young Dominican man whose brother has recently died. Your girlfriend Paloma is the “only Puerto Rican girl on the earth who wouldn’t give up the ass for any reason.” Why? She doesn’t want to make any “mistakes” that would prevent her from going to college and succeeding in life. That’s why you start sleeping with Miss Lora, a teacher who is so skinny that she “made Iggy Pop look chub.” Miss Lora makes you cheeseburgers and “gets naked like a pro.” Time goes on. Miss Lora gets a better job, you and Paloma go to different colleges. One of your college girlfriends tries to confront Miss Lora for sexually abusing you, but Miss Lora never enters the door. Years later, you try to track Miss Lora down.

Look at what Mr. Diaz does in the first few pages. After establishing that the bulk of the narrative will take place in the past (“Years later,”), Mr. Diaz heaps the pathos onto the reader. The narrator has some kind of interesting sexual affair and his brother is dead and he’s very in love (sexual and otherwise) and his current girlfriend isn’t quite fitting the bill. The first three sections increase in length; Mr. Diaz is doing what I call the “flood and release.” The reader is given some highly emotional content…and then the narrative jumps, providing the reader with time to digest and contextualize the narrator’s unique situation.

At least one of Mr. Diaz’s lines made me stop and consider what he meant. About halfway in, the narrator describes Miss Lora by saying, “She gets naked like a pro.” I could think of at least two meanings for the sentence:

- Mr. Diaz could be making use of the “like a pro” idiom.

- Mr. Diaz could be referring to people such as prostitutes who do indeed get naked for a living. (I gather that the nudity is a prelude.)

I’m not sure other readers will see ambiguity in the sentence, but the line stuck out to me for whatever reason. I suppose what I’m recommending is that you take a moment to consider something that may not occur to you very much: the literal meaning of idioms. Why do we lightheartedly call a group of judgmental folks a “peanut gallery?” Why have we chosen to point out that congenital complainers are “the squeaky wheels” that “get the grease?” Why does a sale get us “more bang for the buck?” The reader (if fluent in English, of course), absorbs the language as a figure of speech. The real words remain, however. I wonder what linguistics and other really smart people think about this subject. How do the literal and figurative meanings of idioms affect our reading?

Mr. Diaz made a choice in this story that isn’t to my personal taste. I hasten to say that I understand many great writers make this choice…and they’re not necessarily wrong. Mr. Diaz eschews quotation marks in his dialogue. As with any decision, there are costs and benefits. Why do I make the personal choice to use quotation marks? Here are a couple big reasons:

- They eliminate confusion as to which sentences are spoken by a character and which are contributed by a narrator. Maybe it’s just me, but I always find ambiguities and spend time trying to figure out which words are which. When I write a story, I want my reader thinking about the characters and situation, not trying to divine what I mean on so basic a level.

- They offer a clear distinction between dialogue and non-dialogue scenes. When I see a bunch of quotation marks, I know that the writer is crafting a scene between people instead of offering the narrator free rein.

What Should We Steal?

- Imbue your exposition with an ebb and flow. The release of exposition should resemble a pleasant weekend drive. Your foot is sometimes on the gas and sometimes you coast to enjoy the scenery.

- Take a moment to consider the literal meaning of idioms. Literal and figurative meanings influence the way we perceive a sentence, don’t they?

- Complete a cost/benefit analysis to determine whether or not you want to employ quotation marks. Writing is an artistic pursuit, isn’t it? We should all have some justification for the choices we make.

Short Story

2012, Best American 2013, Exposition, Junot Diaz, LeTourneau, Miss Lora, Sarah Jones, Second Person, The New Yorker

Title of Work and its Form: “Going Down on Polypropylene,” creative nonfiction

Author: Alicia Catt

Date of Work: 2013

Where the Work Can Be Found: The piece can be found in Volume 2, Issue 9 of Pithead Chapel, a fine online journal. Go check it out.

Bonuses: Here is another work of creative nonfiction that Ms. Catt placed in The Citron Review. Here is a piece from decomP Magazine about trichotillomania. And another piece from Mary: A Journal of New Writing.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Point of View

Discussion:

At the age of twelve, Ms. Catt was devoted to the environment and lived in perpetual fear of what the other people would say about her. Were any of us at our best at twelve? Ms. Catt was a little overweight and was uninformed and confused about sex. Based upon that last description, I might have thought this piece was about me. But there’s another reason: the piece is in second person. You meet a woman who doesn’t quite belong in small-town Wisconsin who knows a lot about sex. You blush when she simulates a sexual act with a pudding cup. You are sad that Carrie gets abused, but you are glad that her presence pushed you onto a higher rung of the social ladder. Carrie is gone before long and you suffer one more indignity; the soda cans you picked up during a field trip contained ants that crawl around on you during the bus ride back to school. Ah, adolescence.

So the first thing that I noticed about the story was the point of view. The piece has been classified as nonfiction, so I was a bit surprised to see that Ms. Catt employed the second person. After all, this is ostensibly HER story and the events described (pretty much) really happened. (Depending, of course, how much Ms. Catt agrees with Pam Houston’s thoughts regarding truth in nonfiction.) What does Ms. Catt gain by taking HER story and putting it onto YOU?

- Novelty. There are second-person memoirs out there, but you don’t see these kinds of works every day. Readers can be compelled by aberrations from the norm, so Ms. Catt earns attention from her first sentence. (It becomes her responsibility, of course, to keep that attention and does so with some beautiful sentences and turns of phrase.)

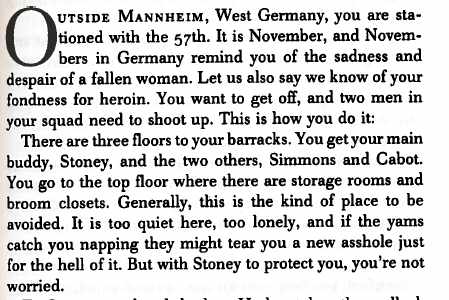

- The reader is aligned with the author. As I’ve pointed out, the second person reduces distance between the narrator and writer; Morgan Freeman is not only talking to you, but he’s telling your story! Here’s the graphic I made using my hype MS Paint skyllz:

- The reader has an easier time remembering his or her own adolescence. It’s been a long time since I was a teenager and I’ve blocked out a lot of the feelings and events I don’t want to remember. Ms. Catt cuts through that defense mechanism with sentences such as, “But you’re made of oddity.” Once Ms. Catt puts you in a mental state in which you can remember how you felt as a teenager, her own awkwardness and longing become more potent.

One of the facets of prose that has been a challenge in my own writing is figuring out how best to cast my scenes. When I was younger, I was often tempted to have my third person narrators go overboard with their DIALOGUE AND DESCRIPTION OF SMALL EVENTS. In that way, I was failing to make use of the fiction writer’s toolbox. In a play or screenplay, a writer has no narrator (you know what I mean) and can really only make use of dialogue and action. Fiction writers can make use of a narrator who simply tells the reader what they need to know and fast-forwards when they need to.

There are no SCENES in “Going Down on Polypropylene,” though there is plenty of scene work. Consider this scene from Ms. Catt’s piece:

You beg your mother for rides to Econofoods, and burrow through the grocer’s dumpster to recycle every scrap of corrugated cardboard they’ve mistaken for waste. Even when you cut your fingers on sticky, dark things, you keep digging and sorting. You dig and you sort until your mother’s had enough and drags you home.

See how boring that scene would be if it were written as a real scene?

Alicia stood before the grocer’s dumpster, plastic bags on her hands in a futile attempt to prevent her from touching the slimy garbage. She loved the environment, but the aroma of hot, wet garbage made her sick.

Alicia’s mother was inside and would be done shopping soon. Alicia had to be quick. She opened up the clear recycling bag and started grabbing for cardboard. Sharp edges nipped at her fingers…

See? Boring. And not just because I wrote it. Ms. Catt makes the felicitous choice to tell us enough to imagine the scene without getting bogged down in the boring and unnecessary.

What Should We Steal?

- Select an unexpected point of view. Why not a second person memoir? Why not tell the story of a historical event from a first person point of view?

- Allow your narrator to describe scenes instead of writing them as scenes. In prose, the narrator can zip through time, reach into the minds of others and work all kinds of other magic. Take advantage of these superpowers!

Poem

2013, Alicia Catt, Pithead Chapel, Point of View, Second Person, trichotillomania

Title of Work and its Form: “The Sex Lives of African Girls,” short story

Author: Taiye Selasi (on Twitter @taiyeselasi)

Date of Work: 2011

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story debuted in the Summer 2011 issue of Granta. It was subsequently selected for Best American Short Stories 2012 by Heidi Pitlor and Tom Perrotta.

Bonuses: Ms. Selasi is on quite a roll! Here is the Montreal Quarterly review of her first novel, Ghana Must Go. Here is what The Rumpus thought of the book. Here is an essay Ms. Selasi wrote about contextualizing her heritage. Here is what Karen Carlson thought of the story. (She really liked it!)

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Narrative Pace

Discussion:

In this second person story, you are an eleven-year-old girl who is living with her extended family. Edem longs for her mother, but is surrounded by a colorful cast of relatives and servants. The story is split into nine sections, through the course of which we learn a great deal about the role that women of all ages play in Ghanian society. Edem is a fascinating age; young enough to be surprised when she walks in on her uncle…receiving…pleasure, but old enough to feel a stirring for Iago, a good-looking houseboy who changed his name out of love for Shakespeare. (I wonder why he chose Iago.) The story begins and ends as the citizens of Accra celebrate. By contrast, “you” are the subject of attempted abuse, unpleasantness that is thankfully interrupted by Auntie. The experience inspires a sad epiphany that will likely color the rest of “your” life.

It’s no surprise that Ms. Selasi’s debut novel has garnered extreme praise from reviewers; her writing is crying out for a vast canvas and her characters are deep and complicated. “The Sex Lives of African Girls” is most certainly a short story, and a very good one, but its structure is fairly different from those of the other stories in this edition of Best American. Through the course of nine numbered sections, Ms. Selasi tells Edem’s story and introduces her extended family and gets into a big discussion about gender roles in places like Ghana.

Ms. Selasi is using the second person to reduce emotional distance between Edem and the reader, which could have made it harder for her to address the culture at large. After all, a third person narrator would have had the freedom to say anything it wanted, regardless of time or location or character focus. Ms. Selasi began and ended the story at a big party, which eliminated some concerns. The reader grows to understand eleven-year-old Edem’s surroundings because they are all laid out in front of Edem, too. The non-Ghanian reader gets a taste of the culture as they meet people like Comfort and (of course) Uncle. I was reminded in some way of the wedding scene at the beginning of The Godfather. Are Italian, American or Ghanian parties really substantially different? Nah; people are the same all over. Ms. Selasi’s structure allows us to experience the little differences between cultures.

The story teaches the reader how to understand it. Ghanian culture may be a little bit obscure for some readers, so Ms. Selasi begins with a basic primer. Thinking about eleven-year-olds as anything but little baby children is certainly not normal for most people, so Ms. Selasi gives Edem a dress that is too long, resulting in a wardrobe malfunction. The hierarchy in Edem’s family (and in their servants) is unfamiliar, so Ms. Selasi employs flashbacks to teach us. Once we get the lay of the land in Edem’s life, we can properly empathize. (And boy, do we empathize!)

The narrative begins somewhat slowly as Ms. Selasi builds her world. Once that has been accomplished, she speeds up the events a little. There’s an honest-to-goodness action sequence in section VII that is a lot of fun to read. Edem runs through the homestead, making brief mention of everything that is happening along the way. “Sex Lives” isn’t a story about characters in isolation, but ones who populate a much larger world. The sequence allows you to see servants preparing for a party, “your” crush kissing your cousin and a muscular naked man before “you” change into new clothes. (The sequence even relates to the theme!) The first half of the story is a little bit slower before it speeds to a conclusion. Ms. Selasi creates suspense and tension by varying the pace.

What Should We Steal?

- Teach your reader how to understand your work. The reader is willing to believe anything you tell them, so long as they are properly prepared.

- Speed up the pace of your narrative once the background has been established. Think of exposition like a set of training wheels; once the reader can stay upright in the world you’ve constructed, go ahead and vary the pace of your story.

Short Story

2011, Best American 2012, Granta, Narrative Pace, Second Person, Taiye Selasi

Title of Work and its Form: “A Chance to Get Involved,” short story

Author: Jeff Moscaritolo

Date of Work: 2013

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story can be found in the Spring 2013 issue of Carve, a lit journal that definitely deserves your attention. (Buy the journal here.) “A Chance to Get Involved” received an honorable mention in Carve‘s Esoteric Awards.

Bonus: Here is a story Mr. Moscaritolo published in Paper Darts.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Narrative Focus

Discussion:

“A Chance to Get Involved” is told in the second person. You are dating a writer named Bess and your relationship was very strong in the beginning, but has soured. Bess is very sad about the tsunami that has just ravaged the Japanese coast and has knocked out the nuclear power facility. You are a schoolteacher who is friends with Chloe Olson, a beautiful young English teacher who is more focused on you than Bess seems to be. You discover that Bess has taken off to Japan in an attempt to help; she calls you, but doesn’t know when she’ll be returning. Why did she leave? She doesn’t quite know for sure, either. Like it or not, Chloe Olson is present and pleasant and even cares about people; you bond over the school’s food drive. As the story ends, the reader doesn’t quite know what will happen in your story, but has a good idea.

Mr. Moscaritolo’s story relates to the theme of the Spring 2013 issue of Carve: disasters. Lots of ink has justifiably been spilled in describing the actions of those who cleaned up after the tsunami. Those stories are certainly important, but Mr. Moscaritolo offers a glimpse into the collateral damage caused by the event. Now, I’ll happily admit that the Japanese victims who lived near the Fukushima Daiichi plant had it much worse than the second person narrator of the story. There’s nothing wrong, however, with telling the stories of the many people across the world who were devastated in different ways.

In fact, Mr. Moscaritolo’s story is a good model for other kinds of work. We’re all deeply saddened by the internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II and there are plenty of works in which the internees’ stories are told. (And there’s now a musical starring George Takei!) What about looking at such an event through the eyes of a different character who has a different perspective? Gosh, I wonder what the guards thought each day as they contemplated what they were doing to fellow citizens because of their different country of birth. What about those who administrated the internment? What if such a person realized that what he was doing was wrong? What about a non-Japanese-American who falls in love with an internee? What would that be like? The primary accounts of, in this case, internees will always be the most historically important and compelling, but it’s also interesting to take a look at an important event through a different lens.

So many great works of literature depict people of high stature and low doing their best to represent humanity in the most moral manner possible. Those works are great. Mr. Moscaritolo makes an equally valid choice that many writers pass up. Bess is off in Japan trying to do something great for humanity. Sure. But this story is about a man who is really thinking of the tsunami’s effect on his own life: his wife is gone, he may succumb to the desire to canoodle with Chloe Olson. The author and reader do not minimize the human misery that took place on the other side of the world. Instead, they are filling in their understanding of the world and people around them.

A small note: I love that Mr. Moscaritolo referred to the pretty English teacher as “Chloe Olson” so often. Why the first name and the surname? I don’t know what Mr. Moscaritolo was thinking, but I think that the narrator’s choice to call her “Chloe Olson” repeatedly is a kind of musical refrain. When we have affection for someone, doesn’t their name become a kind of a song? (I remember making a song of the name of a girl I had a crush on in first grade. Sorry…I’m not telling her name.)

What Can We Steal?

- Tell the story of a tangential character to understand different sides of a big event. What would the plot of Star Wars be like if told from the perspective of a plumber on the Death Star?

- Depict all facets of humanity: bravery and cowardice, altruism and selfishness. People can’t be good and honorable all the time…what fun would that be?

- Reveal a character’s thoughts about another through the names they choose to use for each other. The use of nicknames can indicate familiarity; you already knew that. But there are subtler ways to across a character’s attitude toward another, including the repeated use of a full name.

Short Story

2013, Carve, Jeff Moscaritolo, Narrative Focus, Second Person

Title of Work and its Form: “Last Cookies,” creative nonfiction

Author: Kim Adrian (On Twitter: K_Adrian)

Date of Work: 2013

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story made its debut in New World Writing‘s Winter 2013 issue. You can read the story here.

Bonuses: How interesting! Ms. Adrian wrote an essay about knitting for that same issue. Here is a short story that Ms. Adrian placed in AGNI Online.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Point of View

Discussion:

Ms. Adrian’s short short story is told in the second person. “You” are coping with the impending loss of your aunt, a woman “you have always resembled.” You enjoy making her cookies and you realize that you will someday make her “last cookies,” though you don’t know when. Before long, it is too late. As the story ends, your aunt is off of solid food and no longer wants cookies. Instead, she is only interested in finding some measure of peace.

One reason Ms. Adrian’s story succeeds is that she had a great idea and latched onto it. “Last Cookies” is a particularly sad and potent little idea. We start eating cookies when we’re children and we down quite a few of them during the course of our lives. (Some more than others, of course.) But a “last cookie?” It’s a particularly sad concept. In a way, Ms. Adrian is borrowing from the toolbox of a poet, identifying a particularly potent idea and meditating upon it. Ms. Adrian’s story is not very long, so the power of the idea is not diluted.

Ms. Adrian lists “Last Cookies” on her web site under the category of “MEMOIR, LYRIC, and PERSONAL ESSAYS.” The fact that there is literal truth to the story (not just emotional truth) makes the point of view an interesting choice. What could it mean that Ms. Adrian is telling a true and personal story in second person? Well, the second person could make YOU more likely to enjoy what you have and to make some cookies for a loved one right now, while you can. With so much grief and sadness in the world—I guess I’m bummed out today—the second person cuts through the natural tendency to shy away from confronting the grief of others. Perhaps this is really Ms. Adrian’s aunt (if so, my condolences), but she has made the choice to tell you it is YOUR aunt to cut through that defensiveness. There’s another option: perhaps Ms. Adrian’s grief was so overwhelming that she had to put an emotional scrim between herself and the description of her aunt’s decline. Whatever the “correct” answer is, Ms. Adrian’s POV choice inspires a great deal of high-level thought: a worthwhile result.

What Should We Steal?

- Latch onto a powerful central idea or metaphor. The next time you’re jolted awake by a meaningful thought, jot it down and make it the star of your next poem or short story.

- Select the point of view that will invite your reader to think deeply and will you’re your emotional relationship with the material. If you need to switch to the third person to tell your own sad and traumatic story, go ahead. If you have a compelling fictional story in mind, adopt the first person in order to establish a closer relationship between narrator and reader.

Creative Nonfiction

2013, Kim Adrian, New World Writing, Second Person

Title of Work and its Form: Buffalo Soldiers, novel

Author: Robert O’Connor

Date of Work: 1992

Where the Work Can Be Found: The book was published by Vintage and can be purchased at all fine local bookstores, including Oswego, New York’s River’s End Bookstore. Or from Amazon. Or Powell’s. Just buy it.

Bonuses: Why not check out the New York Times review of the book? The novel was also adapted into a film starring Ed Harris and Joaquin Phoenix. Here’s the trailer.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Description

Discussion:

Specialist Ray Elwood is an Army man stationed in Germany, but he’s not the kind of soldier you see in the recruiting posters. Elwood uses and sells drugs and works in Colonel Berman’s office, writing letters and helping the colonel write scholarly articles about the art of war. You have to grease a lot of palms and out-think a lot of people if you’re in Elwood’s line of business, and he’s always a step ahead. Even when a new Top arrives. Sergeant Lee doesn’t like Elwood very much; as a former drug user, he can see right through Elwood’s façade. Sergeant Lee also has a beautiful young daughter, Robyn, who has lost most of an arm for reasons I won’t divulge. As you might expect, Elwood’s situation deteriorates through the novel and Elwood has new and greater dragons to slay. The first three-quarters of the book is a page turner; the last quarter is a breathless race to an inevitable conclusion. Re-reading this summary, you might not realize the book is a dark and powerful comedy that is grounded in real human emotion.

Mr. O’Connor happened to be one of my teachers at Oswego State. (To my great honor, he’s currently one of my colleagues in the Creative Writing Department.) One of the many reasons he’s a strong teacher is that he offers customized advice to each student in the service of honoring the student’s literary goals above all. This is a policy that was also held by my great teachers at Ohio State, and a goal I have today in my own teaching. You want to write an experimental thriller starring an anthropomorphic stapler? That is not at all the style of fiction that I personally enjoy, but great. Let’s make this the best killer stapler story we can. You have a sentimental and sincere love story in mind? That’s not my bag, but what can we do to make this the sweetest and least complicated love story possible.

I have no idea how many students do what I did each time I had a new writing teacher: I got one of his or her books or read some of his or her stories. (Or plays.) You may not wish to write a book like Buffalo Soldiers, for example, but you can tell immediately that Mr. O’Connor is a master of description and excellent at maintaining narrative momentum. Understanding his work allows you to ask more specific questions and to interact in a more meaningful manner. It’s also a lot of fun to talk to writers about their work. I remember having a question about one of Erin McGraw’s sentences when I read it…as her student, I was welcome to e-mail her and ask her specific questions about her craft! (Most writing teachers love talking to students, don’cha know.) Think about it in another, less scholarly way. Can it really hurt you if your teacher sees you walking around with a copy of his or her book? (Especially if it’s not from the library!)

Okay. Let’s get to the lessons you can steal specifically from Buffalo Soldiers and not just its author. I have to acknowledge the elephant in the critical room. Many folks have heaped laurels upon Mr. O’Connor because of the way he used the second person in his book. (I may be wrong, but it seems as though this point of view has been used more since the Buffalo Soldiers/Bright Lights, Big City era.)

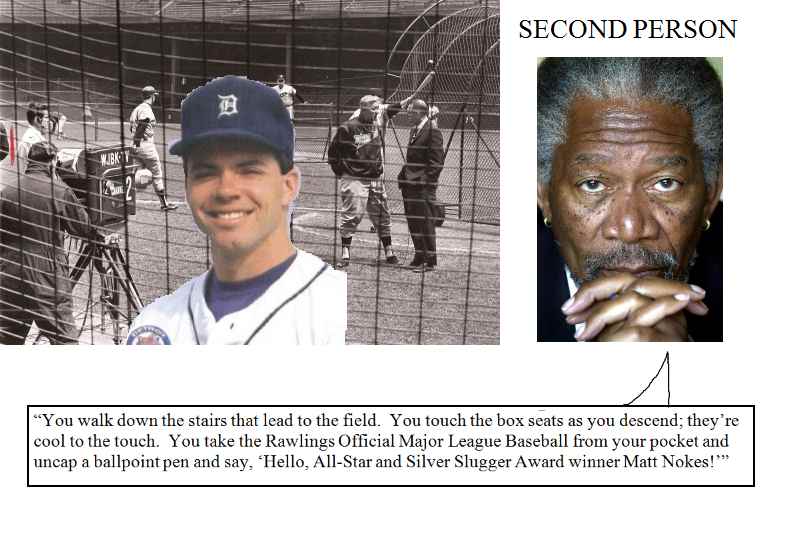

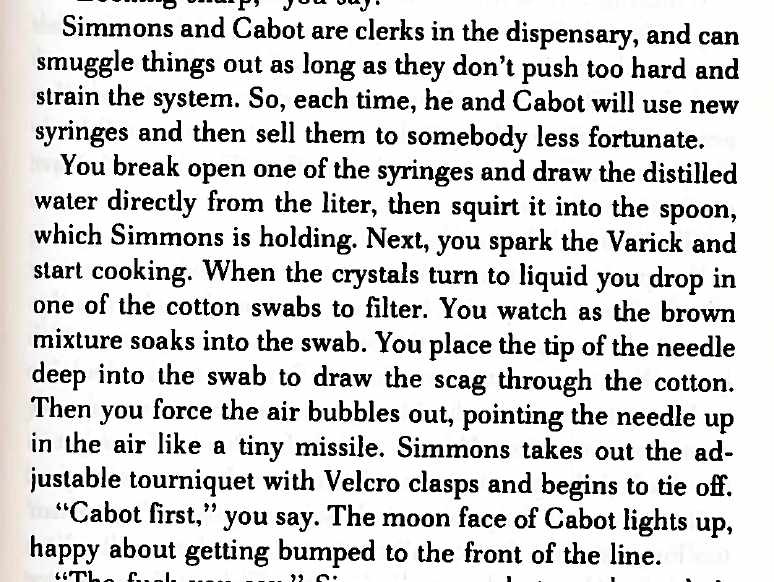

One of the primary advantages of a second-person POV is that you’re explicitly forcing the reader into sympathizing with your character. Check out the very beginning of the book:

Mr. O’Connor accomplishes a lot with the first two paragraphs:

- The first sentence establishes the second person POV.

- You learn that Ray Elwood (the protagonist) is in the military and is stationed in Germany.

- You learn that Ray is not exactly a happy man.

- You find out that Ray enjoys heroin and is the leader when it comes to helping others use the drug.

- You discover that Stoney is the muscle in the group.

- It’s immediately clear that Ray likes to break the rules and knows how to work around them.

So Mr. O’Connor does indeed help you relate to Ray with the use of the second person POV. More importantly, the POV creates a more visceral understanding of some “extreme” actions. How many of us know what it’s like to cook and shoot heroin? When you read the book, “you” do. I’m wagering that few folks who read this know what it’s like to patronize a German brothel. Well, through the use of the second person, “you” do. The decreased narrative distance between the reader and Ray helps bridge the gap between them and makes some dangerous and exotic plot developments seem a lot more normal. If the book were in the first person, some readers may have been more judgmental of Ray’s actions as Ray tried to explain himself to the reader. In the third-person, the narrator may have seemed very far away from a character who, on some level, just wants others to understand him.

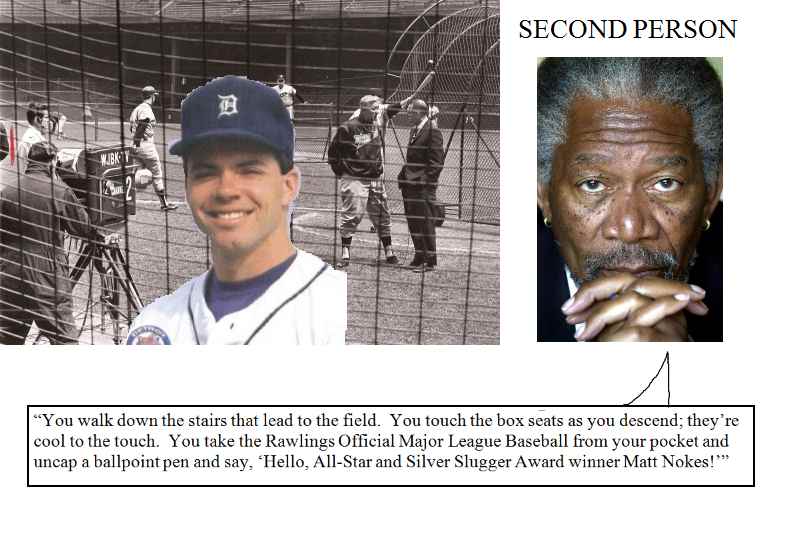

Mr. O’Connor also provides a master class in description. I hate needles…the narration of the drug use scenes made me just as uncomfortable as if I were in a doctor’s office to get a tetanus booster. One of the characters decides to get circumcised; the description made me shift in my chair as I read. Look at the way Mr. O’Connor describes the cooking of heroin, a procedure with which many readers may be unfamiliar:

His sentences are short and relatively simple. There are plenty of complicated and beautiful sentences in the book, but Mr. O’Connor doesn’t employ them here. Mr. O’Connor wows you with his ability to make music with words, but ensures that he is very clear as to what a heroin user does with the cotton balls.

I won’t spoil the ending, but it’s stellar. It’s no surprise that Ray gets himself into some big trouble. Mr. O’Connor sticks the landing, so to speak. The ending addresses all of the conflicts that he has introduced during the course of the book. In the space of a few pages, all of the book’s questions are resolved. Even better, the promise of the character of Ray Elwood is fulfilled.

What Should We Steal?

- Read the work that has been produced by your teachers and be open to all kinds of mentors. On one hand, it may be great for a pure mystery writer to work closely with a teacher who only writes mysteries. On the other hand, lots of great teachers work, teach and/or write in all genres and their primary goal is to help you with your specific story.

- Employ second person to help your reader feel experiences that are alien to them. The second person knocks down some of the barriers between the reader and characters who may be engaged in unusual or unexpected activities.

- Provide lush and simple descriptions for exotic actions. Your reader may not know what it’s like to speed down the Autobahn or to take a tank for a joyride. Ensure that you describe such actions in simple and powerful terms. (You know…if you have access to a tank, I would love to find out what it’s like to go for a joyride in the first person.)

- Concoct a conclusion that connects all of the questions you’ve contrived. The ending of a novel (or a song or short story or nonfiction piece) is like the blossoming of a flower. You have planted and pruned and fertilized…now it’s time to enjoy the logical end of all of your labor.

Novel

1992, Description, Oswego State, Robert O'Connor, Second Person