In Part 1, I discussed five elements of craft we can steal from The Hunger Games books. For Part 2, I thought I would take a close look at some of the prose Ms. Collins put into her book. Let’s jump right in like Katniss diving into the water that keeps her from the Cornucopia:

6. Open your piece with promises that don’t take too long to fulfill.

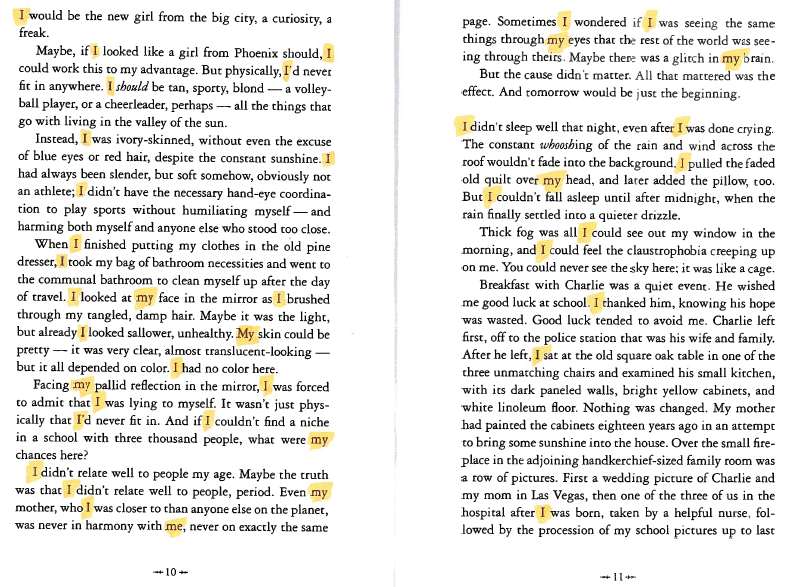

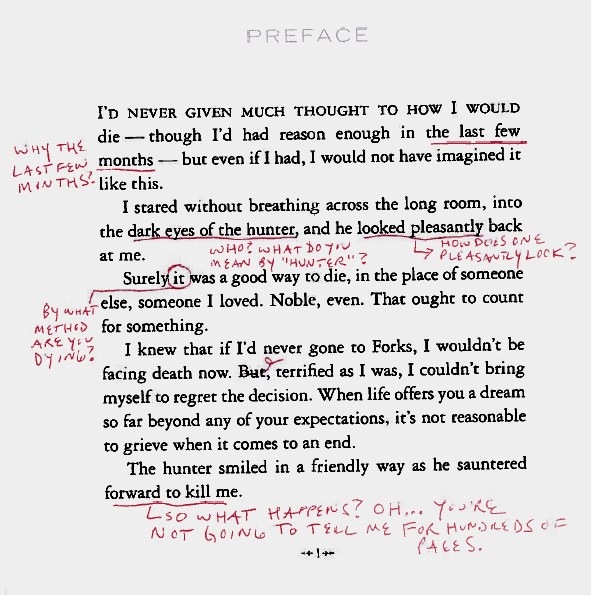

Let’s compare the opening of the first Twilight book to that of Catching Fire. The former begins thus:

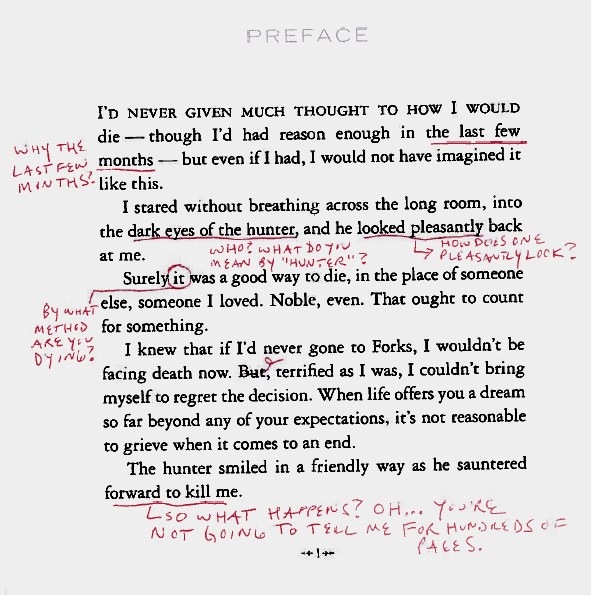

Yes, Ms. Meyer starts her story in the middle of some action, but the tension introduced by this opening scene is not going to be resolved for a very long time. Further, Ms. Meyer brings up a lot of questions and offers a great deal of vague prose. Who is this “hunter?” How is the first-person narrator about to die? Even if we’re curious about this poorly defined conflict, we have quite a way to go until we figure out what is going on.

Yes, Ms. Meyer starts her story in the middle of some action, but the tension introduced by this opening scene is not going to be resolved for a very long time. Further, Ms. Meyer brings up a lot of questions and offers a great deal of vague prose. Who is this “hunter?” How is the first-person narrator about to die? Even if we’re curious about this poorly defined conflict, we have quite a way to go until we figure out what is going on.

Think of it this way. Many parents like to record the moment they tell their children that the family is going to Disney World. Look at how happy this young lady is upon hearing the news:

Now imagine that the mother said, “We’re going to Disney World…eight years from now.”

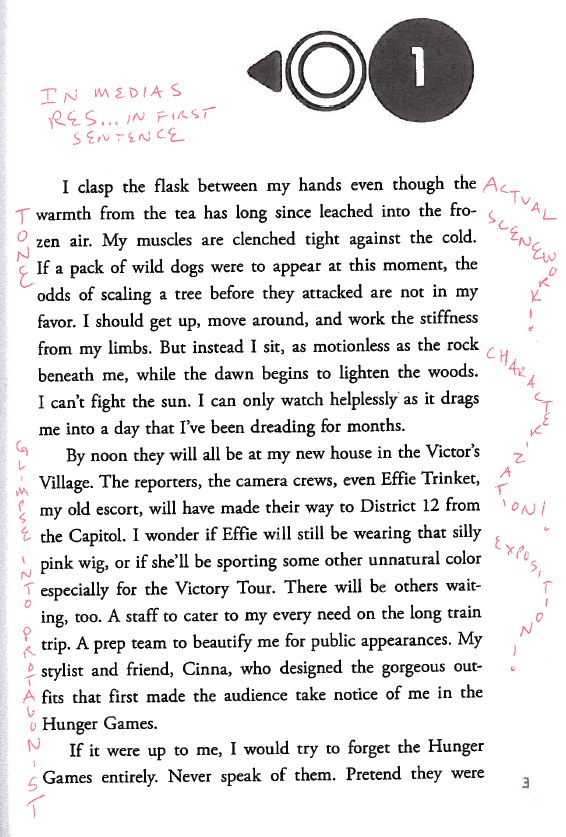

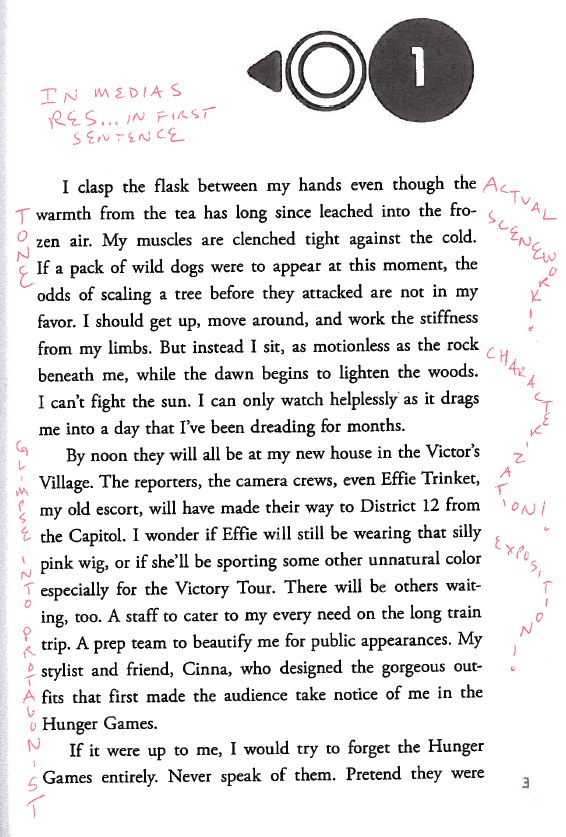

Ms. Collins begins Catching Fire thus:

No, there is no hunter literally stalking Katniss as she reclines on the rock. There is, however, a great deal of tension. Katniss is weary. She’s sore. She needs a vacation. But Effie and the others will be around to bother her very soon. This tension will be capitalized upon very soon. More importantly, Ms. Collins doesn’t present a zillion questions that won’t be answered for a long time. The opening page also offers a great deal of characterization and contributes to the tone of the book.

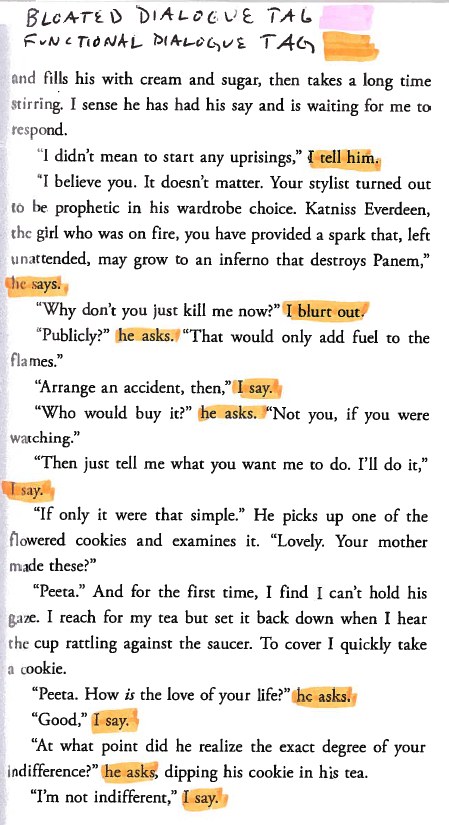

7. Avoid weighing down your prose with redundant and bloated dialogue tags.

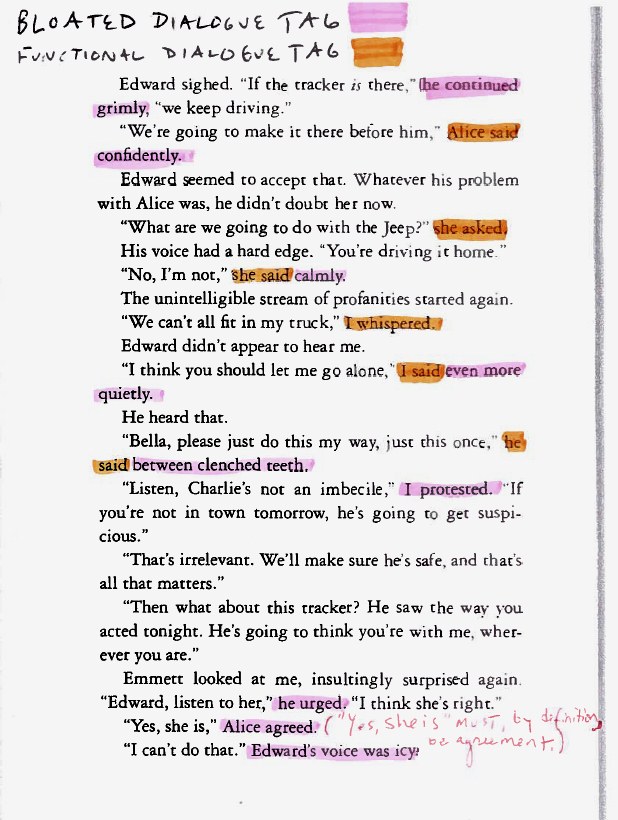

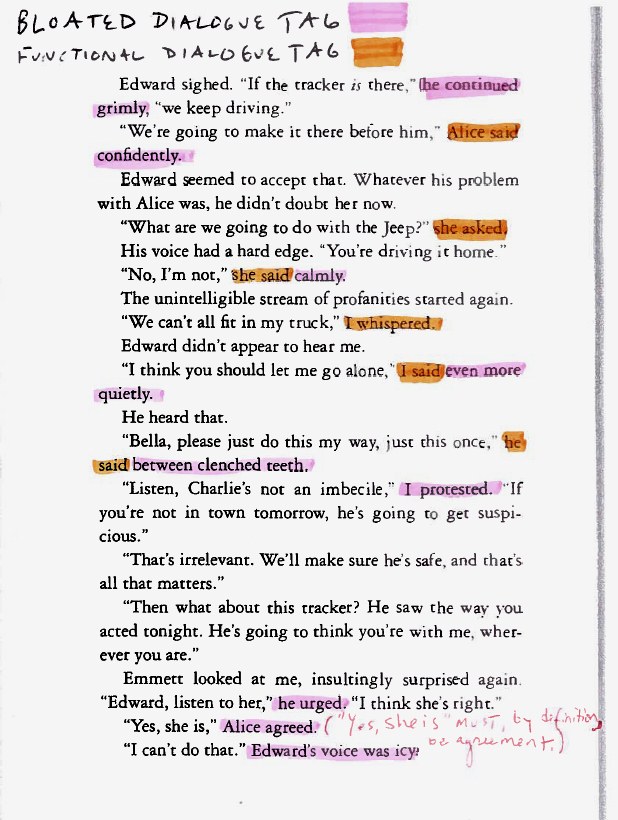

Dialogue tags are like balsa wood. They can hold things together, but you shouldn’t put too much weight on them. Look at the bloat in some of the dialogue from Twilight:

ADVERBS. SOOOOOOOOOOO MANY ADVERBS. ADVERBS EVERYWHERE, AS FAR AS THE EYE CAN SEE. Let your characters do some of the work. You’ll wear your reader down if EVERY line is modified in some way. Further, bloated dialogue tags can result in redundancies. Alice’s response at the bottom of the page is, by definition, an agreement with Emmett’s statement…but Ms. Meyer tells you again that Alice is in agreement.

ADVERBS. SOOOOOOOOOOO MANY ADVERBS. ADVERBS EVERYWHERE, AS FAR AS THE EYE CAN SEE. Let your characters do some of the work. You’ll wear your reader down if EVERY line is modified in some way. Further, bloated dialogue tags can result in redundancies. Alice’s response at the bottom of the page is, by definition, an agreement with Emmett’s statement…but Ms. Meyer tells you again that Alice is in agreement.

Allow your characters’ statements to carry the emotion. In general, you should avoid the adverb unless your character is taking a tone we wouldn’t expect from the line. For example:

“I’m so angry at you because you’re irresponsible!” Ken’s ex-girlfriend shouted angrily through her rage with her eyes in an infuriated squint.

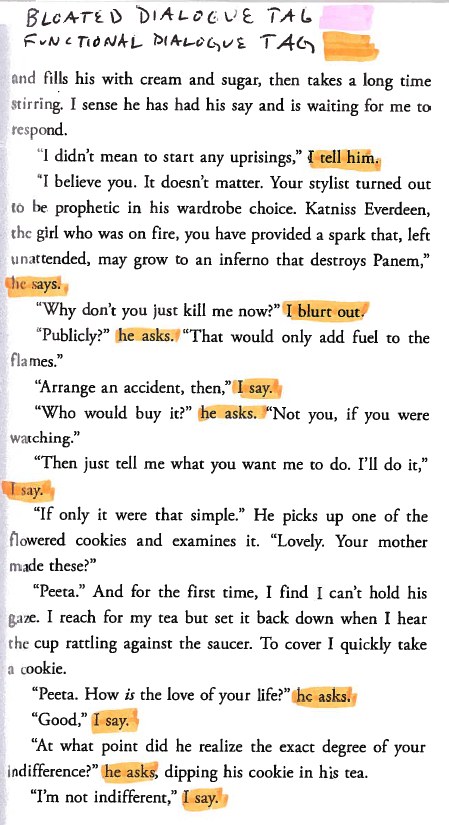

Don’t we know that Ken’s ex-girlfriend is justifiably angry and filled with rage and fury simply based upon what she says between the quotation marks? Now look at a page of Ms. Collins’s dialogue:

This exchange comes toward the beginning of Catching Fire. Katniss and President Snow are having a very calm argument while sizing each other up. The lines themselves do all the work and the reader doesn’t need to wade through a zillion adverbs.

This exchange comes toward the beginning of Catching Fire. Katniss and President Snow are having a very calm argument while sizing each other up. The lines themselves do all the work and the reader doesn’t need to wade through a zillion adverbs.

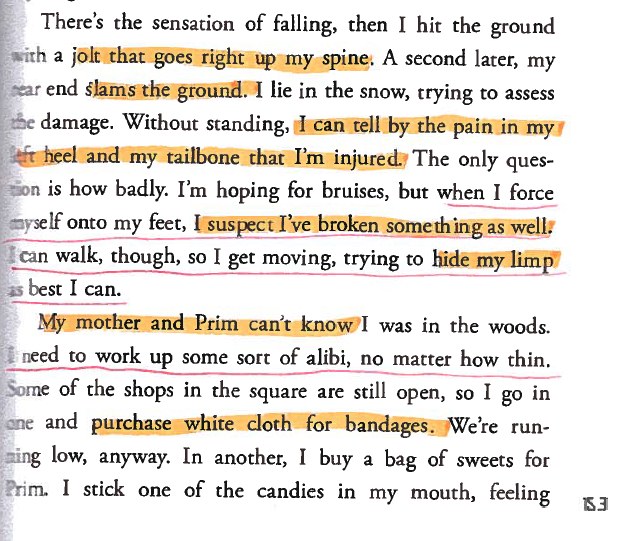

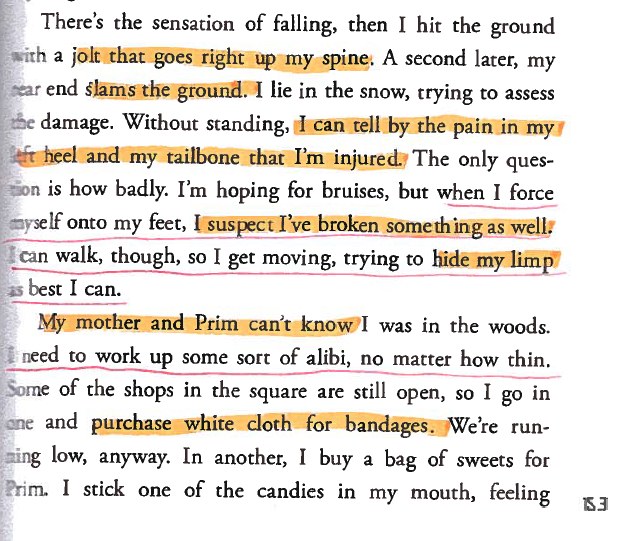

8. Create tension with nagging injuries instead of catastrophic ones.

Somewhat early in Catching Fire, Katniss finds herself on the wrong side of the now-electrified border fence. Ms. Everdeen knows she needs to get back home before she gets caught. Ordinarily, this is not a problem for our Girl on Fire; she’s a skilled athlete. After climbing up a tree, she makes her way across a limb. She’s almost home free when…

Under normal circumstances, it’s no problem for Katniss to get home and to convince the bad guys that she has been good. If anyone notices her limp, however, they will ask questions that could have problematic answers. There’s a delightful tension to the scene with the Everdeen Family and the Peacekeepers. Will someone notice Katniss is in pain? The suspense is killing me!

Under normal circumstances, it’s no problem for Katniss to get home and to convince the bad guys that she has been good. If anyone notices her limp, however, they will ask questions that could have problematic answers. There’s a delightful tension to the scene with the Everdeen Family and the Peacekeepers. Will someone notice Katniss is in pain? The suspense is killing me!

I may cry as I bring up another example…

Ordinarily, it’s no problem for Miguel Cabrera to mash the ball into the stands.

When he has a groin injury, however, long-suffering Tiger fans must suffer through a great deal of suspense that ends in heartbreak. Sigh.

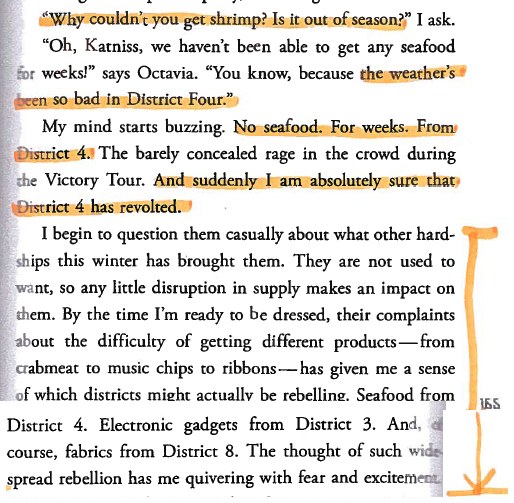

9. Place your characters in a well-defined and realistic world, but avoid overwhelming your reader.

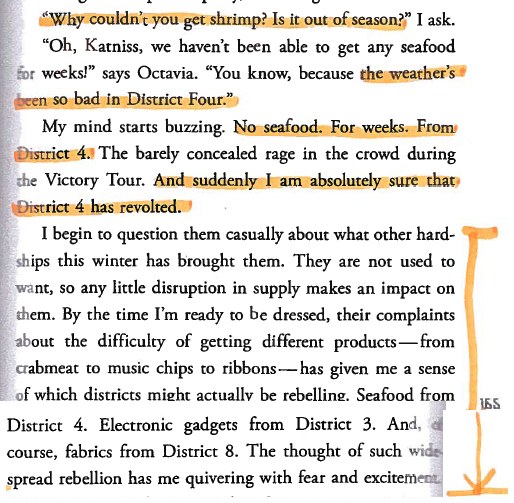

Panem doesn’t necessarily need to be more than just THE WORLD IN WHICH THE HUNGER GAMES TAKES PLACE. A ten-year-old who reads these books isn’t required to draw the kind of map I showed you in Part 1 in order to understand what is happening. That child doesn’t need to know what “panem” means. Hardcore devotees, of course, are welcome to perform complicated analyses of the economic and sociopolitical conditions in each of the Districts. Ms. Collins manages to make Katniss’s world feel real, but doesn’t force me to get a pad and paper and keep notes on everything. Here’s an example:

Okay, so I could do the math. District 4 has a lot of waterfront property. District 3 must have a lot of factories and highly skilled engineers. District 8 is the textile center of Panem. Importantly, the sections such as these aren’t homework. All I need to know in order to enjoy the story is that each of the Districts has different resources. The world feels like a real place, even though every acre is a part of Ms. Collins’s daydream.

Okay, so I could do the math. District 4 has a lot of waterfront property. District 3 must have a lot of factories and highly skilled engineers. District 8 is the textile center of Panem. Importantly, the sections such as these aren’t homework. All I need to know in order to enjoy the story is that each of the Districts has different resources. The world feels like a real place, even though every acre is a part of Ms. Collins’s daydream.

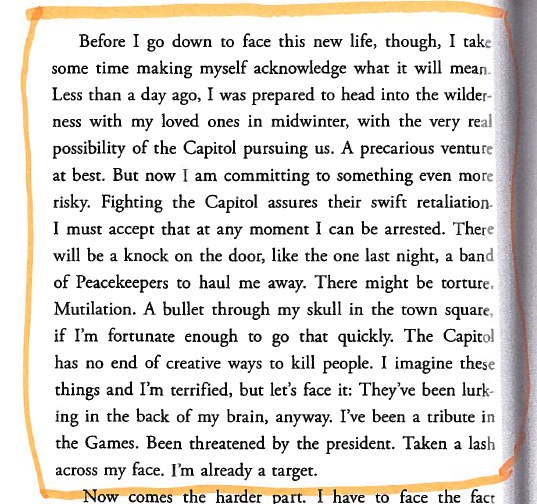

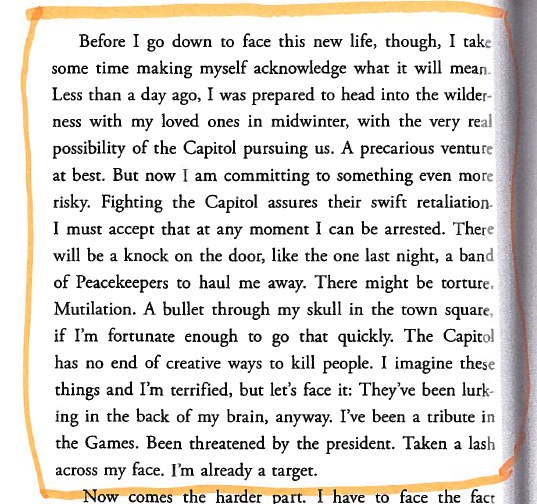

10. Tamp down that desire to write beautiful poetry when flowery prose is inappropriate.

Ms. Collins is capable of writing some beautiful Harlan Ellison/Ray Bradbury/Jane Austen-esque sentences. The first-person protagonist of The Hunger Games, while bright, is not Shakespeare. Katniss, therefore, shouldn’t be given the kind of complicated lines that would be out of reach for someone who grew up poor in a District with poor schools. Here’s an example where I feel that Ms. Collins is balancing her ability and desire to knock you out with poetry, but balances the urge with the reality of the character she created:

The sentences are often short. There are some killer phrases, but the diction is not too high. As always, our ultimate goal is to serve the story. In this instance, Ms. Collins served the story by holding back.

The sentences are often short. There are some killer phrases, but the diction is not too high. As always, our ultimate goal is to serve the story. In this instance, Ms. Collins served the story by holding back.

Novel

Suzanne Collins, The GWS 10, The Hunger Games, Twilight, Young Adult

Suzanne Collins rocketed onto the bestseller lists in 2008 with The Hunger Games, a post-apocalyptic adventure about a young woman compelled to participate in a life-or-death game show that was created by the government to keep citizens in line. The books are considered works of “Young Adult” literature, but their appeal reaches far beyond that single demographic. If you haven’t read the books, it might be a good idea to pick them up or to borrow them from from a young person in your life. Stephen King, master of the page-turner, called the novel a “violent, jarring speed-rap of a novel that generates nearly constant suspense and may also generate a fair amount of controversy.”

Most of us would be lying if we said we didn’t want the same kind of vast and passionate audience that Ms. Collins enjoys. Here are ten elements of craft that writers should consider stealing from the Hunger Games trilogy:

1. Treat Your Reader Like an Adult…Even When They’re Not.

The Hunger Games, is not exactly what many people would consider “appropriate” for young adults. As Mr. King points out:

And although ”young adult novel” is a dumbbell term I put right up there with ”jumbo shrimp” and ”airline food” in the oxymoron sweepstakes, how many novels so categorized feature one character stung to death by monster wasps and another more or less eaten alive by mutant werewolves?

I had much the same experience as Mr. King as I read the books. There’s a lot of death and destruction in these books. And that’s a great thing! (You know, because the books are fiction. Real life violence is a problem.) It’s hard enough to tell a story; it’s still harder when you forbid yourself from depicting the natural consequences of human failings. It’s tempting to want everything to end in a pleasant fashion and for every character to find happiness, but that’s not how the world really works. In other words…

Rue HAD to die.

2. Be Open to Inspiration From a Wide Range of Sources.

Writers must play an unending game of “what if?” Ms. Collins described her moment of inspiration for Publisher’s Weekly:

Collins says the idea for the brutal nation of Panem came one evening when she was channel-surfing between a reality show competition and war coverage. “I was tired, and the lines began to blur in this very unsettling way.” She also cites the Greek myth of Theseus, in which the city of Athens was forced to send 14 young men and women into the labyrinth in Crete to face the Minotaur. “Even as a kid, I could appreciate how ruthless this was,” Collins recalled. “Crete was sending a very clear message: ‘Mess with us and we’ll do something worse than kill you. We’ll kill your children.’ ”

Great things can happen when a writer mashes together her thoughts about increasingly outlandish reality shows, coverage of the war in Iraq and childhood history lessons. Why not flip through Edward Gibbon’s History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire? The book is packed with steal-worthy stories from history.

3. Seize the Reader with the First Person Present.

One of the first things I noticed about the books was that they are written from Katniss’s perspective in present tense. (It just so happens that I’m working on a book that uses the same POV.) Here’s an excerpt of the book’s prose:

Haymitch has never seen me run. Maybe if he had he’d tell me to go for it. Get the weapon. Since that’s the very weapon that might be my salvation. And I only see one bow in that whole pile. I know the minute must be almost up and will have to decide what my strategy will be and I find myself positioning my feet to run, not away into the surrounding forests but toward the pile, toward the bow. When suddenly I notice Peeta, he’s about five tributes to my right, quite a fair distance, still I can tell he’s looking at me and I think he might be shaking his head. But the sun’s in my eyes, and while I’m puzzling over it the gong rings out.

And I’ve missed it! I’ve missed my chance! Because those extra couple of seconds I’ve lost by not being ready are enough to change my mind about going in. My feet shuffle for a moment, confused at the direction my brain wants to take and then I lunge forward, scoop up the sheet of plastic and a loaf of bread. The pickings are so small and I’m so angry with Peeta for distracting me that I sprint in twenty yards to retrieve a bright orange backpack that could hold anything because I can’t stand leaving with virtually nothing.

What does the first person POV accomplish for Ms. Collins? What does the present tense add? Well, a first-time reader knows nothing about The Hunger Games. Experiencing the spectacle through Katniss’s eyes allows us to understand what is “normal” in the book’s society. Katniss doesn’t think it’s at all strange for children to kill each other as they make a mad dash in the direction of a pile of weapons. A third person narrator would have a lot more explaining to do to bridge the gap between the world of the book and our world. Instead, Katniss just gets to tell you about her life and what she’s thinking and feeling.

The present tense adds a lot of suspense. Katniss doesn’t know how her story will end…it’s still happening to her! A reader may have unspoken assumptions that a third person narrator has access to the future. By keeping everything in the present tense, Ms. Collins gets all the more power out of Katniss’s reactions to her problems.

4. Avoid Overwheming Your Reader with the Minutiae of Your World.

I’m certainly not disputing the influence of the Lord of the Rings books and I acknowledge Tolkien’s great achievement. That said, I found it very hard to truly engage with those Middle Earth stories. It seemed to me as though reading all of those books represented an awful lot of WORK that I wasn’t willing to do. As Lee K. Abbott points out, it’s the writer’s job to do all of the work so the reader can have all of the fun. I’ve come across some other works whose authors seem to expect me to get a pad and paper so I can construct the detailed family tree that would allow me to understand the story.

The Hunger Games books, on the other hand, don’t require you to delve into the minutiae of the world of Panem. You don’t NEED to know where District 12 is located in North America. You’re not FORCED to remember how many winners have come from each District. The story is about Katniss and her struggle and Ms. Collins allows you to understand the political intrigue through her eyes, not the other way around. On the other hand, we should…

5. Create a Realistic and Complicated World as Detailed as Our Own.

Ms. Collins may or may not have gone the J.K. Rowling route, compiling a complete history of the Games and of Panem for her own benefit. What matters is that the end result FEELS real. Two very creative folks took to LiveJournal, creating as realistic a map of Panem as they could based upon the details from the books. Ms. Collins put enough love and attention into her novels that you can do this kind of detective work if you really want to.

Look at a site like PanemPropaganda. Ms. Collins created such a realistic dystopia that talented fans are able to recreate the kind of propaganda that is put out by the Capitol. These kinds of efforts are only possible because of the work Ms. Collins did to ensure that everything in the books fit together in a logical fashion and that you could actually live in the world of the book.

Continued in Part Two…

Novel

Suzanne Collins, The GWS 10, The Hunger Games, Twilight, Young Adult

Title of Work and its Form: Twilight, novel

Author: Stephenie Meyer

Date of Work: 2005

Where the Work Can Be Found: You can find the book just about anywhere.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Sentence-Level Issues

Discussion:

Full disclosure: I am not in the target demographic for Twilight and the story and writing don’t particularly do much for me. The worse angels of my nature sometimes whisper in my ear that I should blast books and pieces I don’t feel are particularly good. I learned indirectly that this was the wrong way of thinking from Mrs. Iodice, my AP English teacher. She had us read Jane Eyre, a book that didn’t particularly appeal to me. Should I dismiss such a classic out of hand? Of course not. Even though Jane Eyre isn’t my favorite book, it’s a far more beneficial policy to learn from it than to deride it. The same principle applies to Twilight. Millions of people bought the book and people enjoyed the book, so why not investigate what Ms. Meyer’s book has to teach us?

Create characters and situations that appeal to your target audience.

I know very little about women of any age, but Bella certainly seems like a fairly representative teenage girl. As many cultural critics have pointed out, the book appeals to a young woman’s fear of and desire for sex. Becoming a vampire and losing one’s virginity changes a person into something else. There are severe consequences for those who “turn,” including loss of social status, pregnancy and disease. I’ll happily wager that Twilight has helped countless young people work out their feelings about their sexuality. Ms. Meyer has found great success appealing to these very common psychological dilemmas.

Tread a new path through an old mythology.

Dangerous mythological creatures one sort or another have been with us for just about forever. Vampire conventions have changed over the decades. Ms. Meyer has put her own spin on them. Her vampires sparkle and play baseball and have extensive families. While the publishing market will fluctuate for each kind of creature (vampires may be cold now, but werewolves are hot), there will likely always be an audience for well-written books that take a new look at classic sources of terror.

Okay, with that said, let’s look at some specific sentence-level issues from Twilight that writers must consider in their work.

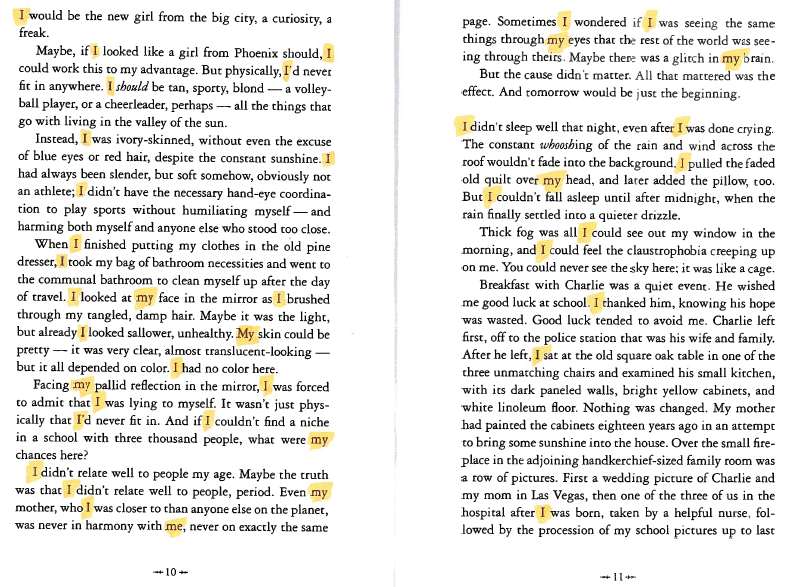

Avoid the overuse of “I.”

If you are writing in the first person, you’re probably going to use “I” and “me” a great deal. The use of the word is sometimes unavoidable. The problem is that the overuse of the word can result in repetitive and lifeless paragraphs. What is the solution? Recast as many sentences as you can without “I.”

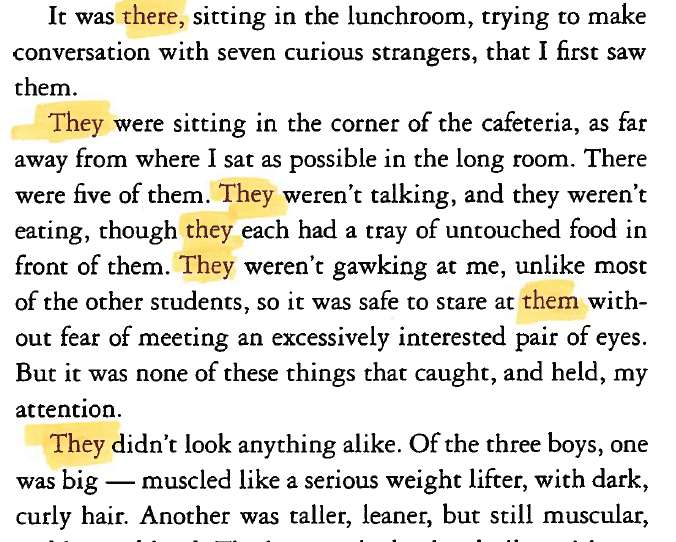

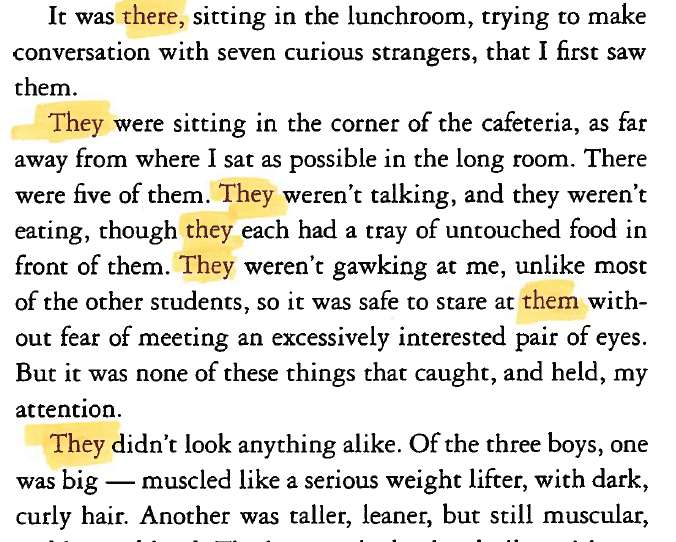

Replace words such as “they” and “there” and “things” with more descriptive terms.

“They” is a very valuable pronoun; the word allows the writer to characterize a group or to describe their actions with great efficiency. Unfortunately, each time you use “they,” you’re missing an opportunity for characterization or detail. Look at the above example. Instead of writing “they,” Ms. Meyers could have taken advantage of the chance to lend more specificity to the work. Here are some examples of what she could have used to replace a “they” or two:

“They” is a very valuable pronoun; the word allows the writer to characterize a group or to describe their actions with great efficiency. Unfortunately, each time you use “they,” you’re missing an opportunity for characterization or detail. Look at the above example. Instead of writing “they,” Ms. Meyers could have taken advantage of the chance to lend more specificity to the work. Here are some examples of what she could have used to replace a “they” or two:

- The creepy vampire family

- The pale people at the table

- Those darn Cullens

- Everyone’s favorite outcasts

Are all of these appropriate? No. But see how these phrases add a lot more to the story than “they?”

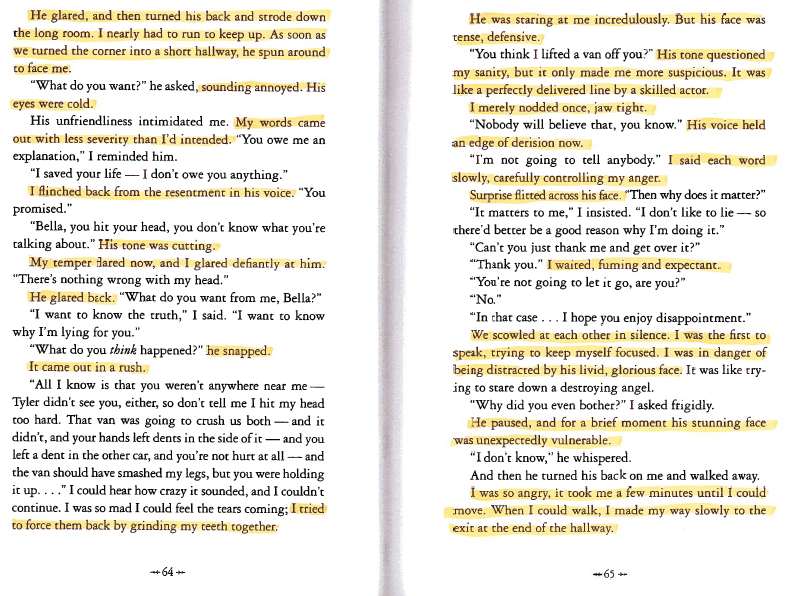

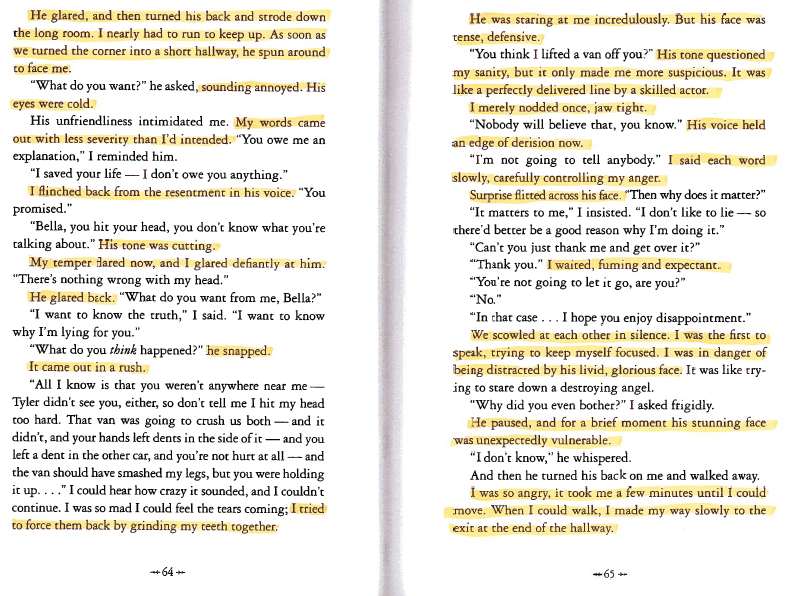

Ignore the need to over-choreograph a scene.

Ms. Meyer offers an awful lot of minute detail for each facial expression her characters make. She could have focused on the important ones, leaving the reader to provide the rest. Think of it this way. What’s wrong with this bit of dialogue?

Ms. Meyer offers an awful lot of minute detail for each facial expression her characters make. She could have focused on the important ones, leaving the reader to provide the rest. Think of it this way. What’s wrong with this bit of dialogue?

“I’m going to kill you, jerk!” He said with anger.

Anger is the expected tone one would use to threaten someone else. You only need to specify the tone of the expression if, for example, the character were joking.

The great Lee K. Abbott would also point out another bit of over-choreography. Ms. Meyer writes, “We scowled at each other in silence. I was the first to speak…” Ms. Meyer did not need to have Bella tell us that she and Edward scowled in silence. How do we know they were silent? There was no dialogue. Further, we know that Bella is the first to speak because she has the first subsequent line. Just as Strunk & White advise us to “omit needless words,” we must also omit needless description.

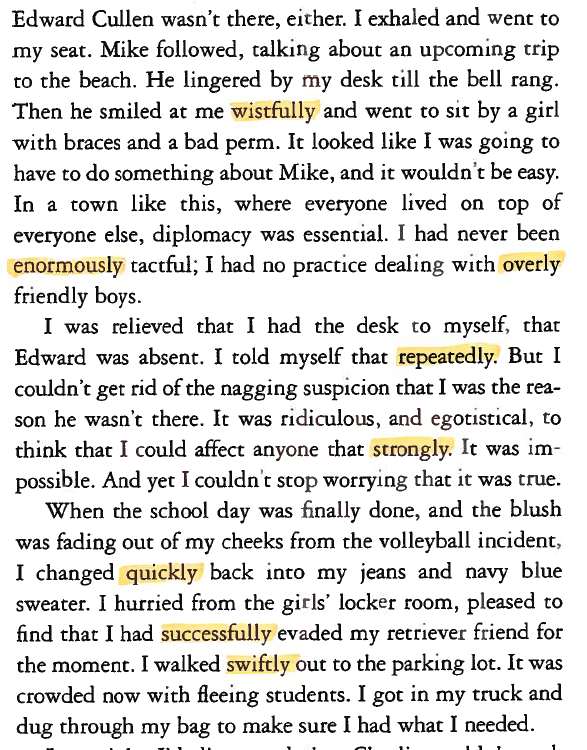

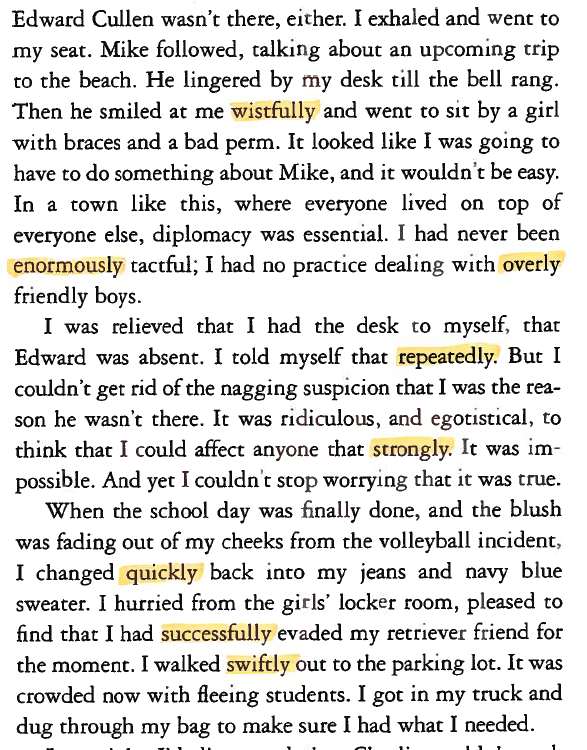

Restrict your use of adverbs.

Remember: adverbs are shortcuts and are often superfluous. Is the word “successfully” necessary in this example? How about saying that Bella “dashed” instead of “walked swiftly?”

Remember: adverbs are shortcuts and are often superfluous. Is the word “successfully” necessary in this example? How about saying that Bella “dashed” instead of “walked swiftly?”

Novel

2005, Sentence-Level Issues, Sparkly Vampires, Stephenie Meyer, Twilight

Yes, Ms. Meyer starts her story in the middle of some action, but the tension introduced by this opening scene is not going to be resolved for a very long time. Further, Ms. Meyer brings up a lot of questions and offers a great deal of vague prose. Who is this “hunter?” How is the first-person narrator about to die? Even if we’re curious about this poorly defined conflict, we have quite a way to go until we figure out what is going on.

Yes, Ms. Meyer starts her story in the middle of some action, but the tension introduced by this opening scene is not going to be resolved for a very long time. Further, Ms. Meyer brings up a lot of questions and offers a great deal of vague prose. Who is this “hunter?” How is the first-person narrator about to die? Even if we’re curious about this poorly defined conflict, we have quite a way to go until we figure out what is going on. ADVERBS. SOOOOOOOOOOO MANY ADVERBS. ADVERBS EVERYWHERE, AS FAR AS THE EYE CAN SEE. Let your characters do some of the work. You’ll wear your reader down if EVERY line is modified in some way. Further, bloated dialogue tags can result in redundancies. Alice’s response at the bottom of the page is, by definition, an agreement with Emmett’s statement…but Ms. Meyer tells you again that Alice is in agreement.

ADVERBS. SOOOOOOOOOOO MANY ADVERBS. ADVERBS EVERYWHERE, AS FAR AS THE EYE CAN SEE. Let your characters do some of the work. You’ll wear your reader down if EVERY line is modified in some way. Further, bloated dialogue tags can result in redundancies. Alice’s response at the bottom of the page is, by definition, an agreement with Emmett’s statement…but Ms. Meyer tells you again that Alice is in agreement. This exchange comes toward the beginning of Catching Fire. Katniss and President Snow are having a very calm argument while sizing each other up. The lines themselves do all the work and the reader doesn’t need to wade through a zillion adverbs.

This exchange comes toward the beginning of Catching Fire. Katniss and President Snow are having a very calm argument while sizing each other up. The lines themselves do all the work and the reader doesn’t need to wade through a zillion adverbs. Under normal circumstances, it’s no problem for Katniss to get home and to convince the bad guys that she has been good. If anyone notices her limp, however, they will ask questions that could have problematic answers. There’s a delightful tension to the scene with the Everdeen Family and the Peacekeepers. Will someone notice Katniss is in pain? The suspense is killing me!

Under normal circumstances, it’s no problem for Katniss to get home and to convince the bad guys that she has been good. If anyone notices her limp, however, they will ask questions that could have problematic answers. There’s a delightful tension to the scene with the Everdeen Family and the Peacekeepers. Will someone notice Katniss is in pain? The suspense is killing me! Okay, so I could do the math. District 4 has a lot of waterfront property. District 3 must have a lot of factories and highly skilled engineers. District 8 is the textile center of Panem. Importantly, the sections such as these aren’t homework. All I need to know in order to enjoy the story is that each of the Districts has different resources. The world feels like a real place, even though every acre is a part of Ms. Collins’s daydream.

Okay, so I could do the math. District 4 has a lot of waterfront property. District 3 must have a lot of factories and highly skilled engineers. District 8 is the textile center of Panem. Importantly, the sections such as these aren’t homework. All I need to know in order to enjoy the story is that each of the Districts has different resources. The world feels like a real place, even though every acre is a part of Ms. Collins’s daydream. The sentences are often short. There are some killer phrases, but the diction is not too high. As always, our ultimate goal is to serve the story. In this instance, Ms. Collins served the story by holding back.

The sentences are often short. There are some killer phrases, but the diction is not too high. As always, our ultimate goal is to serve the story. In this instance, Ms. Collins served the story by holding back.