Title of Work and its Form: “How Our Town Got Its New Name and Some Other Stuff That Happened,” short story

Author: Marie Potoczny

Date of Work: 2012

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story was originally published by the excellent online journal failbetter. Why not check it out right now? It’s free!

Bonus: Here is Ms. Potoczny’s “Donor,” a story that was published in the Apalachee Review. (It’s a PDF.)

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Voice

Discussion:

The story takes place in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. The citizens of New Mecca, Iowa are frustrated and don’t quite know what to do with their anger and despair. They change the name of their town to something more patriotic: Rumsfeld. (Of course.) The residents of Rumsfeld subsequently get revenge…on all of the wrong people. I don’t want to ruin exactly what happens, but it seems to me that Ms. Potoczny intends the piece to serve as an allegory of the public reaction to the George W. Bush era.

The story is told from the perspective of one of the citizens of Rumsfeld. I also tend to believe that the narrator may be the mass consciousness of those who call Rumsfeld home. One way Ms. Potoczny gives this character a unique voice is by allowing him/her/it to make the kind of grammatical errors we all make. Check out the missing punctuation and the comma splices in this section of the very first paragraph:

I mean you could just hardly believe it. We took down the “Welcome to New Mecca, IA” sign, we were gonna do it anyway, but maybe the goat sped things up, and unanimously voted to change the name of our town to something a little more patriotic.

These “flaws” give the narrator some personality and also make sense within the context of the story. The whole point is that the folks who live in the Town Formerly Known As New Mecca are acknowledging the mistakes they’ve made and the flaws that existed in their belief system.

Another thing I love about the story is the allegory hidden inside the central allegory. The residents of Rumsfeld decide to get revenge by peeing into the water supply of the neighboring town. What’s wrong with this plan?

- They’re getting revenge on the wrong people.

- They’re not actually going to hurt any of the folks in Alma

- They’re degrading themselves in the process of attempting revenge

- The citizens of Alma have much more potent forms of protection.

The deeper allegory is that the folks in Rumsfeld are impotent; they desperately want to get revenge and to protect themselves and to feel safe, but can’t figure out how to accomplish these goals. Ms. Potoczny doesn’t employ too heavy a hand in constructing her allegories. The best examples of this kind of literature allows for multiple reasonable interpretations. (I read Animal Farm in fifth grade and thought it was an allegory on the political system in the United States; Orwell’s touch was light enough to make this reasonable.) The least satisfying allegories force you into a critical straitjacket. (I don’t want to list any examples of those.)

Ironically, writing a piece like this is a great way to exorcise some of the anger you may have about political developments. If you’re anything like me, you get really angry about certain things that happen in politics and in culture. I don’t know how Ms. Potoczny feels about any of the pressing issues of the day, but I can definitely imagine that deconstructing the post-9/11 response can provide the kind of catharsis that Rumsfelders were trying to achieve.

What Should We Steal?

- Goof up if its going too reinforce you’re point. Grammatical errors can be particularly appropriate for dialogue and may illustrate why your character is the way they are.

- Shape your allegories with a delicate touch. Allow your reader to make his or her own decision as to what you really meant with your grand allegory. Not only will the comparison mean more to the reader, but you’ll empower readers to choose from more options.

- Exorcise your political demons through the magic of storytelling. You can run for office so you can change things in your country, but that will invite reporters to uncover all the embarrassing things you’ve done. Why not simply write a story that could nudge readers ever closer to agreeing with your philosophies?

Short Story

2012, failbetter, Marie Potoczny, Voice

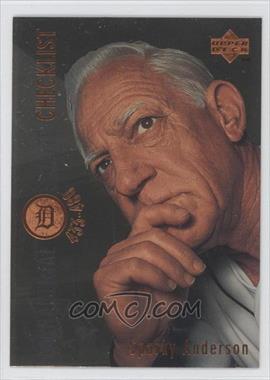

Title of Work and its Form: Sparky!, autobiography

Author: Sparky Anderson with Dan Ewald

Date of Work: 1990

Where the Work Can Be Found: I believe the book is out of print; you can find it at many of the fine secondhand bookstores around you or on the Internet. Mr. Ewald has written a few books about Mr. Anderson; Sparky and Me: My Friendship with Sparky Anderson and the Lessons He Shared About Baseball and Life was released in 2012.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Voice

Discussion:

As a lifelong Detroit Tiger fan, I grew up with Sparky Anderson and Alan Trammell and Lou Whitaker and Jack Morris and all of those guys. They were good—very good—in 1984 and broke my heart in 1987. (I don’t want to talk about what the team was like between 1995 and 2003.) Sparky Anderson was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2000, fitting recognition for his work as a major-league manager. Mr. Anderson reached the majors as a player, but knew that he wasn’t exactly good enough to make a life that way. He began managing the Reds in 1970, winning four pennants and 2 championships with the Big Red Machine. In 1979, he was removed as manager of the Cincinnati club and went to the American League’s Tigers. The 1984 Tigers started the season 35-5 and rolled to a Series victory over the Padres. (Sorry, Tony Gwynn.) Mr. Anderson ended his managerial career in 1995 at the age of 61. He died in 2010, having reached the top of his chosen profession.

Sparky reveals Mr. Anderson to be a very thoughtful man. The book begins with a confession: “My name is Sparky Anderson. And I’m a winaholic.” Mr. Anderson briefly describes his life and how it was influenced by his desire to win and then goes into detail about an interesting incident. The 1989 Tigers were 13-24 and Mr. Anderson had something of a panic attack/identity crisis. He went home to Thousand Oaks, California to take stock of his life. (Don’t we all have occasional dark winters of the soul?) After working out his problems, he returned to the Tigers, refreshed. What should writers steal from the first chunk of Sparky!? Mr. Anderson delves relatively deeply into issues of identity. He describes the difference between George and Sparky. Sparky was the fiery man who would yell at umpires and brood over losses; George was married to Carol and loved visiting children in the hospital.

The most striking part of the book (to my mind) is the voice that Mr. Anderson and Mr. Ewald employ. Mr. Anderson was certainly a very smart man, but he wasn’t the most formally educated man on the planet. You can flip to any page of Sparky! and find sentences with the same kind of diction. The sentences are short. The paragraphs add up to big ideas that could have been condensed into one sentence. Most of them begin with nouns or names. Here’s a representative section:

How does a person attain success?

Longevity. Because success is for the moment…and only that moment. So it must be aqcquired moment after moment after moment. That’s the difference and that’s where a lot of people make a mistake. In baseball, for instance, some guys think if they win one year that they’re automatically successful.

They’re wrong. That’s not success. All that happened was the blind squirrel happened to find an acorn. They could never repeat because they don’t have it in them. They were for the moment. But only for one single moment.

Mr. Ewald didn’t coax Mr. Anderson into longer, more complicated sentences. And that’s fine. Why? When I picked up the book, I wanted to feel as though I were spending an hour with George “Sparky” Anderson, a man with whom I’ve long felt a connection! Mr. Ewald traded the beauty of complicated diction for the simple poetry of authenticity.

I can’t help but interject with respect to a cause that means a great deal to me. Alan Trammell belongs in the Hall of Fame. Plain and simple. He was easily better than Ozzie Smith and Barry Larkin. Sparky agreed with me!

I’ve seen some great shortstops—Dave Concepcion, Ozzie Smith, and Cal Ripken, just to name a few.

I’d take Trammell because of everything he can do. Smith is a wizard in the field and can do more with the glove. Ripken is stronger and hits with more power. But Trammell does everything.

Trammell hits 15 homers a year, knocks in 90 runs a year and always plays around the .300 mark. In the field he never botches a routine play. People take that for granted, but that’s the sign of a great shortstop. If he gets a ground ball, it’s an out.

I’ve seen Trammell carry us in a pennant race after we lost a couple of key people like Lance Parrish and Kirk Gibson. That takes a special kind of player.

What Should We Steal?

- Confront the identity issues that are inherently wrapped up in your story. If you’re writing non-fiction, you’re writing about identity in some way. At the very least, you’re trying to take a person and paste them onto sheets of paper. What are the dilemmas that confront your characters, even if that character is you?

- Employ simple diction when appropriate. Mr. Anderson was brilliant, but he was no Gustave Flaubert. If Mr. Ewald had made Mr. Anderson sound like Shakespeare, the reader would not have such a visceral reaction to the book.

Sparky Anderson (1934 - 2010)

Sparky Anderson (1934 - 2010)

Nonfiction

1991, Baseball, Dan Ewald, Detroit Tigers, Sparky Anderson, Voice

Title of Work and its Form: “Everyday Use,” short story

Author: Alice Walker

Date of Work: 1973

Where the Work Can Be Found: The short story has been anthologized in about a million collections. (And with good reason!)

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Voice

Discussion:

“Everyday Use” is one of my favorite short stories for a lot of reasons. I love the simplicity of the story and the narrator, a woman who is equally proud and vulnerable, simultaneously tough and loving. Mrs. Johnson, along with her younger daughter Maggie, awaits the return of Dee, the daughter who got out of the small town and went to college. Dee returns with a different style of dress and a different name: Wangero. There’s also a boyfriend named Hakim-a-barber. (Mrs. Johnson has misheard the Arabic; I believe his name is “Hakim Akbar.”) Having seen a different way of life, Wangero is no longer pleased with the way she grew up. There is a fight over some quilts; Wangero wants to hang them and cherish them as an artifact of African-American culture and Mrs. Johnson expects Maggie will get them and will use them as, well, quilts. You know, for warmth when it is cold. Wangero and Hakim-a-barber leave after a short argument over what “heritage” really means.

Whenever you write a first-person narrator, it’s vital that you understand the way their voice should sound. Mrs. Johnson is not “book smart,” as her education was ended for her after second grade. (The school was closed. As she points out, “in 1927 colored asked fewer questions.”) It’s therefore unrealistic that Mrs. Johnson would, for example, start quoting Shakespeare or use a lot of “big” words. Walker instead restricts herself to employing fairly short sentences. The poeticism comes through in the more “rural”/”down-home” expressions that Mrs. Johnson uses. Mrs. Johnson is not at all simple-minded; she just expresses herself in a less complicated manner than might be the case if she had more formal education.

Mrs. Johnson describes a dream in which she is erudite and classically beautiful and famous. This dream is immediately followed by the truth: “In real life I am a large, big-boned woman with rough, man-working hands.” Walker introduces the central conflict of the piece while setting the tone. There is rich fantasy in the lives of Mrs. Johnson and Maggie, but that fantasy is as strong as reality. We trust the narrator because she is telling us the story straight.

“Everyday Use” could be considered a kind of attack against Wangero and the fantasy she has chosen. Instead, Mrs. Johnson primarily restricts herself to observing and reporting. There’s subtext in the climactic fight—

Dee (Wangero) looked at me with hatred. “You just will not understand. The point is these quilts, these quilts!”

“Well,” I said, stumped. “What would you do with them?”

—Mrs. Johnson reinforces a tone of loving indignance. Instead of flying off the handle and being vicious to her daughter, she calmly allows the reader to draw his or her own conclusions.

What Should We Steal?

- Match your character’s diction to his or her level of education and mindset. Now, Mrs. Johnson COULD have caught up with formal education on her own, but she didn’t. (She certainly seems very smart to me!) Therefore, Ms. Walker writes Mrs. Johnson’s thoughts in a conversational, relatively unadorned manner.

- Allow your subtext to emerge from the scene instead of making it excessively explicit. I guess this is one of the main reasons I’ve always loved the story so much. There is a HUGE debate going on in the story. What is identity? Who decides what we are and what we will be? How beholden are we to the past? How much should we respect the way we grew up? What does it mean to honor one’s parent(s)? Ms. Walker takes a step back narratively and allows Mrs. Johnson to simply report the story and allow us to confront the debate on our own terms, just as we would if we happened to walk by Mrs. Johnson’s house mid-argument.

Short Story

1973, Alice Walker, Classic, Voice

Title of Work and its Form: “You Don’t Love Me Anymore,” pop song

Author: “Weird Al” Yankovic

Date of Work: 1992

Where the Work Can Be Found: The song was originally released on the album Off the Deep End. In 1992, MTV (which stands for “Music Television”) played music videos instead of simply pointing an HD camera at Snooki while she pees in a pool while accidentally drinking out of someone’s chaw cup. You can watch the music video for the song at Mr. Yankovic’s VEVO page. (Yes, I know the first 45 seconds or so of the song are missing.)

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Voice

Discussion:

“Weird Al” Yankovic really isn’t weird at all. Since the early 1980s, he has been satirizing and parodying popular culture. You can tell he’s special because most novelty acts don’t experience the kind of lasting success that Mr. Yankovic has described. What sets him apart? He’s insanely talented in a number of ways. 1992’s Off the Deep End was a mainstay in my off-brand Walkman in addition to his earlier albums. (UHF is a modern classic!) Sure, we all love his parody songs. “Like a Surgeon”…“Smells Like Nirvana”…”White & Nerdy”…”Eat It”…”Amish Paradise”…”Another One Rides the Bus”…the list goes on. What sets Mr. Yankovic apart is the fact that he’s actually a great musician and can write great songs in a wide range of styles. He’s produced songs that would not have been out of place in Tin Pan Alley and would fit on albums by Brian Wilson and Devo and countless others.

“You Don’t Love Me Anymore” is a simple and beautiful love song. The first-person narrator is singing to a lover who has recently grown cold and distant. The narrator laments:

We’ve been together for so very long

But now things are changing; oh, I wonder what’s wrong.

The second verse takes a decidedly darker turn:

I guess I lost a little bit of self-esteem

That time that you made it with the whole hockey team.

And then the bridge takes the narrative in a new direction:

Why did you disconnect the brakes on my car?

That kind of thing is hard to ignore;

Got a funny feeling you don’t love me anymore.

The song is funny because the narrator does, in fact, ignore the very clear signs that the woman no longer loves him. (And may feel he no longer deserves to live.) The song ends with a restatement of the gentle guitar and synthesizer part.

Mr. Yankovic gets maximum humor out of the well-crafted song by starting in the normal world we all understand. We’ve all been in relationships in which the other person’s attitude has changed and we’re left to wonder why. As each verse progresses, however, this girlfriend’s signs become clearer.

Oh, darling, I’m begging, won’t you put down that knife?

I still remember the way that you laughed when you pushed me down the elevator shaft.

What’s this poisonous cobra doing in my underwear drawer?

(If you’ll notice, the narrator asks several questions in the lyric, reinforcing the idea that he’s not exactly catching on.) Mr. Yankovic employs a solid dramatic and comedic structure. He starts out small and gets bigger and bigger and includes increasingly humorous and violent non-sequiturs. (The girlfriend pulls out his chest hairs with an old pair of pliers and poisons his coffee… “just a little each day.”)

The couplets Mr. Yankovic employs also serve him well. The listener realizes very quickly that a joke is coming up. Part of the fun is guessing what the rhyme will be. Who else would rhyme “problems when” with “bathtub again?” In a different song, longer and more circuitous lines would be more appropriate. (If you’re a “Weird Al” devotee, I’m thinking of the song “Pancreas.”)

Mr. Yankovic also uses his voice to great effect. Like many great rockers, Mr. Yankovic sings in a manner that fits the song. For example, Billy Joel goes for a pretty tone when singing a lullaby and a far more grizzled timbre in a faster rocking-out number. In “You Don’t Love Me Anymore,” Mr. Yankovic does his best to mimic the sweet-but-tough tone that exemplified the sound of love songs performed by rock bands in the late 1980s and early 1990s. There’s also a kind of unique stamp in Mr. Yankovic’s voice that immediately lets you know the song is his.

What Should We Steal?

- Begin in the real world and then bring your audience into the world you’ve created. Your audience needs to understand the unique world you’re creating in your piece. Once, for example, the listener knows “You Don’t Love Me Anymore” is about a love gone wrong and the narrator is oblivious, the writer can make increasingly outlandish jokes. Think of it this way; do you show a man or woman the craziest parts of your personality on a first date? Probably not; you ease them into your personal brand of dysfunction. (And they do the same for you, of course.)

- Employ the kind of narrative voice that suits your narrator. If your first-person narrator is a good-hearted and dim-witted custodian at a TV station, he should misunderstand what his bosses say while doing his best to comply with the wishes of the boss. A long-suffering secretary from Queens who has dreams of being a newswoman should growl and whine and say that things “suck” in front of her boss.

- Maintain an interest in all kinds of creative endeavors. Mr. Yankovic clearly enjoys all kinds of music and understands how it’s put together. Isn’t life more fun if you can enjoy Chamillionaire and R. Kelly as much as The Beach Boys and Led Zeppelin and Barenaked Ladies and Toni Basil?

Song

"Weird Al" Yankovic, 1992, Voice