Writers are asked many general questions about their craft.

…”What is your overarching philosophy regarding the inherent power of fiction?”…”What IS–character–to you?”…”What is the position of place in your work?”…

These are great and important questions, but I’m really curious about the little things. In the “Hey, Why’d You Do That” series, I ask accomplished writers about some of the very small choices they made during the process of composition.

Jim Pransky is an interesting man who has the kind of career to which many of us aspire. He’s been a baseball scout for many years and is currently with the Colorado Rockies. When he isn’t identifying talent and evaluating young men for their suitability to make it in The Show, he likes to write books about our great National Pastime. In addition to writing biographies of overlooked players that deserve attention, Mr. Pransky writes novels that use baseball as their setting. Continue Reading

Novel

Jim Pransky, Why'd You Do That?, Young Adult

Writers are asked many general questions about their craft.

…”What is your overarching philosophy regarding the inherent power of fiction?”…”What IS–character–to you?”…”What is the position of place in your work?”…

These are great and important questions, but I’m really curious about the little things. In the “Hey, Why’d You Do That” series, I ask accomplished writers about some of the very small choices they made during the process of composition.

Matthew Norman first came to my attention when I saw a Twitter notification about the Lit Hub piece he published in May 2016. I obviously have a very soft spot in my heart for writers; as a born showman (though not a good performer), there’s little I fear more than taking the stage, only to see no one is watching. In prose that is hilarious and full of heart, Mr. Norman tells the story of giving a reading to an audience that primarily consisted of chairs, tables and people who were trying to skim half a dozen $100 art books they wouldn’t buy while sipping a $3 coffee. Continue Reading

Novel

Harper Perennial, Matthew Norman, Why'd You Do That?

Writers are asked many general questions about their craft.

…”What is your overarching philosophy regarding the inherent power of fiction?”…”What IS-character-to you?”…”What is the position of place in your work?”…

These are great and important questions, but I’m really curious about the little things. In the “Hey, Why’d You Do That” series, I ask accomplished writers about some of the very small choices they made during the process of composition.

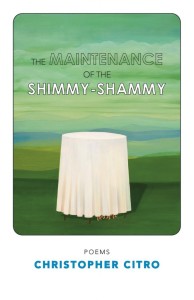

Christopher Citro is one of those writers whose names seem so familiar because you keep seeing it in all of your favorite lit mags. His work has appeared in a ton of places, including The Journal, Ploughshares, Redivider and a number of other journals you wish would accept your own work. His first book of poetry, The Maintenance of the Shimmy-Shammy, was published by Steel Toe Books. Why not order a copy directly from the publisher? You can also find the book at Barnes & Noble and Amazon.

Yes, you may wish to read 10,000 words in which Mr. Citro elucidates his overall philosophy of poetry. Instead, I am curious about the tiny choices that Mr. Citro wrestles with every time he sits down to put pen to paper. I read and enjoyed “Nerve Endings Like Strawberry Runners,” a poem that Mr. Citro placed in Witness. Why not follow along with the poem and reflect upon the nitty-gritty of his writing process in order to improve your own work? Continue Reading

Poem

Christopher Citro, Why'd You Do That?, Witness

Writers are asked many general questions about their craft.

…”What is your overarching philosophy regarding the inherent power of fiction?”…”What IS-character-to you?”…”What is the position of place in your work?”…

These are great and important questions, but I’m really curious about the little things. In the “Hey, Why’d You Do That” series, I ask accomplished writers about some of the very small choices they made during the process of composition.

Deborah Guzzi is a Connecticuter whose poetry has been published in markets all over the world. Some of that work appears in 2015’s The Hurricane, a collection published by Prolific Press. Please consider purchasing the book directly from them, but you can also get the book from Amazon or Barnes & Noble.

You can (and should!) learn more about Ms. Guzzi through her Twitter feed and her YouTube page.

Ms. Guzzi was kind enough to suggest we discuss her poem, “The Sowing.” The poem is available here for free. I was touched by how much she clearly loves her poem and feels that the piece is doing good with respect to domestic violence and rape: issues that are near and dear to the hearts of many of us. As my Ohio State MFA colleague Laurel Gilbert is also greatly interested in these problems, I thought it would be interesting to see what she would ask Ms. Guzzi about her poem. (I was right.) Continue Reading

Poem

Deborah Guzzi, Prolific Press, Why'd You Do That?

Writers are asked many general questions about their craft.

…”What is your overarching philosophy regarding the inherent power of fiction?”…”What IS-character-to you?”…”What is the position of place in your work?”…

These are great and important questions, but I’m really curious about the little things. In the “Hey, Why’d You Do That” series, I ask accomplished writers about some of the very small choices they made during the process of composition.

Caille Millner is a columnist and editorial writer for the San Francisco Chronicle. In those pursuits, Ms. Millner has a responsibility to the truth. Thankfully, she also enjoys the occasional adventure on the fiction side of the tracks. One of these is “The Surrogate,” a story that appeared in Joyland Magazine.

Ms. Millner is available on Twitter. Once you are done reading her story and the reasoning behind some of her choices, why not send her 140 characters about how much you liked her story?

1) The inciting incident is super clear in the story. Franco says he wants to have a “baby of his own” with Cecily. The confession changes the story, just like a good inciting incident should. But then you go several pages without addressing Franco’s request again; you spend a lot of time telling us about their marriage and how Cecily’s surrogacy works.

How do you think you maintained tension in the narrative while putting the main conflict aside for a little while?

The work of surrogacy is naturally tense, just by the simple facts of how it works. A woman who needs money performs the labor of pregnancy for someone else, according to someone else’s rules and standards — and she often has to do so while caring for her own children and her own family.

That’s a situation fraught with all kinds of emotions. Yet we’ve mostly chosen to keep all of these details under wraps. Think of how many times you’ve read in a newspaper that someone wealthy gave birth “via surrogate,” as if the surrogate were a machine instead of a human being.

They aren’t machines, they’re women, and there’s usually a stark class divide between the surrogates and their clients. The U.S. is one of the only developed countries that allows paid surrogacy — most of the others feel like the attendant ethical questions are too much for them to handle, as a society. We don’t even talk about the ethical questions.

But that silence makes the situation rich ground for storytelling and exploration. Simply unrolling the details of Cecily’s situation creates a feeling of tension in the reader, because when as you slowly let the details sink in, you realize that everything about Cecily’s situation is emotionally extreme.

2) At least a few of the sentences in your story are what I call “backwards sentences.” For example:

“It’s the closeness of the way that they have to live that makes her uneasy.”

“To cool the house they’ve got all the lights off;…”

How come you put the subject of the sentence (or clause) so far in?

The narrative POV in this story wasn’t too far away from the subjects, so I occasionally wrote the narration in a way that they might speak themselves. It keeps up the rhythm of their voices.

3) This happens about 60% of the way through the story:

“He smiles and gets up to go into the black maw of the kitchen, bringing back a beer for himself and a diet soda for her. She isn’t supposed to drink the diet sodas but she does anyway.”

What’s this choice all about? I guess I understand that Cecily has decided to take mild risks by drinking caffeine during pregnancy. But why did you make Franco bring her the diet soda?

It’s a small gesture that seemed natural to their relationship. And it’s in keeping with their personalities. Franco is a decent, considerate man who would like to do more for everyone than he’s currently capable of doing. Cecily is sitting down, outwardly passive, but in reality doing far more work than other people feel comfortable enough to acknowledge.

4) About halfway through, the narrator’s mind-reading powers shift from focusing on Cecily to focusing on Franco. I know you had to do that because Franco and Omar had to do some stuff together in the story without Cecily there.

What made the POV switch in the story okay?

Because it’s a story about their relationship, and about how this massive, bizarre situation that they’re in has affected their ability to connect and to give to each other. There are two people in that equation, and the readers needed to hear from the other one.

5) Last lines are always really important! Here’s yours:”Cecily has to nearly choke before she realizes that she’s been holding her breath while she watches.”

Those words stick out for me: “has to nearly choke.” The rest of the sentence flows, but “has to nearly choke” feels to me like the kind of speed bump that means something. What was your thinking there?

I’m glad you caught that! I wanted to give the reader a physical sensation very close to the one she was experiencing in that moment. If you say the sentence aloud, you’ll notice that running all of the syllables together is difficult, the sequence of words deliberately slows you down. It’s a way to collect all of the unspoken tension and emotion so that you can feel it again before you leave this family.

Caille Millner is a writer, essayist, and memoirist. She’s the author of The Golden Road: Notes on my Gentrification (Penguin Press), an editorial writer and weekly columnist for the San Francisco Chronicle, and has had essays in The Los Angeles Review of Books and A New Literary History of America. Her awards include the Barnes and Noble Emerging Writers Award and the undergraduate Rona Jaffe award for fiction.

Short Story

Caille Millner, Joyland Magazine, Why'd You Do That?

Writers are asked many general questions about their craft.

…”What is your overarching philosophy regarding the inherent power of fiction?”…”What IS-character-to you?”…”What is the position of place in your work?”…

These are great and important questions, but I’m really curious about the little things. In the “Hey, Why’d You Do That” series, I ask accomplished writers about some of the very small choices they made during the process of composition.

Katherine Riegel is a friendly woman and a good teacher. She’s also a co-editor at Sweet: A Literary Confection. Most of all, however, Ms. Riegel is a writer who loves creating poetry and creative nonfiction.

In November of 2014, Ms. Riegel published a powerful piece of creative nonfiction at Brevity. Go ahead; check out “Run Towards Each Other.” Then come back here and see why the author did what she did.

1) You begin “Run Towards Each Other” with the following two sentences:

“It is Thanksgiving, again. My smile is a weapon cutting off access to my grief-treasure.”

So…”grief-treasure” isn’t a real word. I even copied it into Microsoft Word to make sure. Then I looked on dictionary.com. Then I realized you must have made it up for some reason.

How did you decide to combine those two specific words? Why did you include the hyphen?

KR: Such an interesting question! I deliberately wanted to link those words in order to make sure the metaphor was clear. I imagined the smile/weapon protecting treasure—something precious, something coveted, something collected over time. So a stranger might see only the weapon, the defense—the smile. But the treasure being protected is actually grief. So it was layers of metaphor: smile=weapon, grief=treasure. In asking the reader to engage with complex metaphor, I didn’t want language itself to make understanding any more difficult. So I…bent language to make it do what I wanted. And I think the comparison of grief to treasure in particular is so unexpected, so out of the norm in terms of the ways we usually talk about grief, that I didn’t want the reader to be able to interpret it any other way.

2) The third paragraph is all one sentence. And there are en-dashes that split the sentence into three sections in addition to commas and everything else that makes up a sentence.

Why did you decide to combine all of those clauses? How did you make sure that the reader would know what you meant to say? What was the effect you hoped to create?

KR: Microsoft Word wasn’t happy with that sentence. (Though actually the 3rd paragraph is 2 two sentences, which itself is problematic because the 2nd “sentence” is technically two fragments separated by a dash.) In the first sentence of that paragraph, the dashes did what dashes are generally supposed to do, in that, if you took out the material inside the dash, the grammatical structure of the sentence, and its essential meaning, would be unaffected. Oh, and incidentally those were em dashes in my document; I think the formatting of the site turned them into en dashes. I wanted to put some description of my own smile into the piece, but I knew if I didn’t limit it that I could go on and on in the most unflattering ways about my own smile. This made it essential to keep the image short, tucked within a sentence. I also deliberately left out the “and” before “my new loves” because I wanted the three items in the list to be equal. Somehow adding “and” would make it feel like the last one, the “new loves,” was either more or less important than the other two. I intended the order to be more chronological than by importance.

I think also that this particular paragraph, reflecting my (the narrator’s) self after my mother’s death, is particularly fragmented. All the clauses, as you say, are both linked and separate, connected only tenuously through punctuation. The speaker, too, is just barely held together, and still doesn’t quite believe how or why she is. As for the 2nd sentence, where I get to write “me—me,” I confess I gave myself permission to do that because of some lines/line breaks in a Sharon Olds poem. It’s called “His Stillness” and the sentence reads like this:

At the

end of his life his life began

to wake in me.

She deliberately ended a line with a throwaway word—“the”—in order to get a line which begins with “end,” ends with “began,” and has “his life” repeated in the middle. I wasn’t breaking my mini-essay into lines (though I did when I first wrote it—shhh, don’t tell) but there was something really important about repeating that word “me.” The narrator doesn’t feel worthy of the support she’s gotten, so she must repeated the word “me” to persuade herself she matters, even as that words is followed by “insignificant.”

3) So, “toward” and “towards” are interchangeable, but “towards” has that extra Zzzzzzzzzzzz sound at the end. “Toward” has a nice, crisp consonanty ending.

Why did you use “towards?”

KR: I have to confess this may be just dialect. I grew up in Illinois with parents from DC and Pennsylvania who went to school in Vermont. When I take “accent quizzes,” it nearly always gets my accent wrong because of that. (I say “ca-ra-mel,” for example, not “car-mel.”) I guess, when I think about it, “towards” sounds more together-y to me. People are running towards each other—everyone is doing the action. A person would run toward a house, because the house wouldn’t be doing the action. Or maybe I’m completely full of it, and I’m a teacher, so I can come up with an answer even if I have to make it up. 🙂

4) I’m pretty sure Grammar Girl would tell you that you didn’t need that comma in the sentence, “It is Thanksgiving, again.”

How come you put that comma there?

RM: Oh, yes. Very important, and very deliberate. I wanted to emphasize “again.” It is inevitable, it keeps coming around even when you don’t want it to. Putting the comma there was to try to show the dread, to make the reader feel just how much the narrator didn’t want it to be Thanksgiving—again. Oh boy. Here we go.

5) And here’s the penultimate sentence:

“In the barn I will pull carrots out of my pockets and hold them flat on my palms.”

“In the barn” is a dependent clause that begins a sentence. All of those nerds who complain about grammar stuff might say that you shoulda put a comma after “In the barn.”What made you leave the comma out?

KR: Really interesting punctuation questions! I think language has a music to it, a rhythm. Grammar and punctuation rules are in place to help with clarity, but we all know many of them are arbitrary and some are based on the rules of Latin, which early English grammarians decided was the only “proper” language and so must be imitated. In this case, it’s clear what’s happening, and I heard the sentence in a particular way in my head. It wasn’t interrupted by a pause after “barn.” I’m one of those people who hears a voice very clearly in my head when I read; I don’t read my work aloud much during revision because it’s redundant. I heard this sentence as a whole, the image words like fence posts, regularly spaced: barn, carrots, pockets, flat, palms.

It’s odd to see how often I bend/break grammar and punctuation rules, when I emphasize clarity in both those areas as a teacher. I suppose I’m more concerned with syntax and its possibilities than with absolute rules. I want writing to be precise, in order to get across nuance and subtlety. That kind of precision requires a writer to make considered choices that sometimes break rules.

Katherine Riegel is the author of two books of poetry, What the Mouth Was Made For and Castaway. Her poems and essays have appeared in journals including Brevity, Crazyhorse, and The Rumpus. She is co-founder and poetry editor of Sweet: A Literary Confection, and teaches at the University of South Florida. Visit her at www.katherineriegel.com.

Creative Nonfiction

2014, Brevity, Katherine Riegel, Sweet: A Literary Confection, Why'd You Do That?

Writers are asked many general questions about their craft.

…”What is your overarching philosophy regarding the inherent power of fiction?”…”What IS-character-to you?”…”What is the position of place in your work?”…

These are great and important questions, but I’m really curious about the little things. In the “Hey, Why’d You Do That” series, I ask accomplished writers about some of the very small choices they made during the process of composition.

Ravi Mangla is a very successful gent. In addition to his Outpost19 book, Understudies, Mr. Mangla has placed his work in some very cool journals, including Mid-American Review, American Short Fiction and Wigleaf. He’s also written for BULL Men’s Fiction, a personal favorite of mine.

Now, we could be overwhelmingly jealous of Mr. Mangla, but jealousy is an emotion suitable only for country songs. It would be far more profitable for us to enjoy his work and to try and learn from what he does well. You may wish to share a nine-hour phone call with him in which you ask only one question and expect him to answer. But if Mr. Mangla offered such a service, he would have no time to write! Instead, Mr. Mangla has been gracious enough to offer his insight into some of the small decisions he made in “Feats of Strength,” a short short he published in Tin House‘s Open Bar blog.

1) “Feats of Strength” features two lines of dialogue. One happens in present tense-the strongman commits to buying the car-and one happens in the past: Natalie wonders how she and her husband could have been so negligent as to purchase a defective baby crib.

Why did you put the spoken lines into italics instead of using the good, old-fashioned quotation marks? How come you did the same thing for both lines of dialogue, seeing as how one took place in the past and the other took place in the present?

RM: Dialogue is a bit of a spoiled brat, demanding not only distinctive markings but an entirely new paragraph (soon it will be asking to be underlined). Aesthetically, I don’t find the appearance of quotation marks particularly pleasing. Whenever possible I use plain text or italics. Only if the clarity is compromised will I roll out the quotes.

2) About 55% into the story, you have the first person narrator tell us the name of his child:

“-his name is Dev, by the way-“

Why didn’t you just write, “my son, Dev” instead? The clause that names Dev breaks up a sentence and also seems like more obvious and brash narration than the rest of the piece. Why’d you do it that way?

RM: I hoped it would lend some naturalism to the piece. The omission of the child’s name until late in the story suggests a fallibility on the part of the narrator. In a piece like this, with a contrivance like a strongman at its center, I have to work twice as hard to keep the reader from seeing the strings. Sometimes a small disruption, a note of dissonance, can disarm the reader and help them to buy into the narrative.

3) The strongman decides to bring his new car home in an unorthodox manner. Instead of just driving it home, he gets some exercise by pulling it there instead. You tell the reader:

“With a tow hook, he attaches a thick rope to the underside of the front bumper.”

The sentence seems to be pretty simple and declarative. Why did you put the clause with the tow hook at the beginning of the sentence? Why not just write,

“He attaches a thick rope to the underside of the front bumper with a tow hook.”

RM: I chose that phrasing solely for the sake of sentence variation. The previous sentence started with he, and I was hesitant to replicate it. I don’t want the sentences to become too predictable or monotonous.

4) In the final paragraph, the family waves goodbye to the now-inconvenient automobile. You write:

“The strongman reaches a bend in the road, disappears behind a cluster of trees.”

Why’d you remove the conjunction (I’m guessing you would choose “and”) and plop in that comma?

RM: Often I’ll exclude a conjunction between clauses for rhythm. It sounds jazzier to me (but perhaps not to every reader). It’s a habit I picked up from reading Sam Lipsyte. I’m a huge admirer of his language craft. His sentences have such a unique cadence.

[Editor’s Note: Mr. Mangla makes a good point. If you’re not familiar with Sam Lipsyte’s work, why not check out this New Yorker story he wrote. Or one of his books? You get the drift.]

5) The story is bookended with appearances from “several women in the neighborhood” who sit in their yards and watch the scene. You don’t mention them elsewhere in the story and they don’t affect the narrative directly.

Space is at a premium in a short short. This story is 671 words long. Why did you devote 27 words-slightly more than 4% of the text!-to the women? What, in your mind, is their function?

RM: They exist to underscore the strangeness of the scene. If there was a strongman lifting a car in my neighborhood, I know I’d be standing around watching. I think they also help to open up the world of the story, so the scene isn’t happening in a vacuum.

Ravi Mangla is the author of the novel Understudies (Outpost19, 2013). His work has appeared in Mid-American Review, American Short Fiction, The Collagist, Gigantic, The Rumpus, Wigleaf, and McSweeney’s Internet Tendency. Follow him on Twitter: @ravi_mangla.

Short Story

2014, Outpost19, Ravi Mangla, Tin House, Why'd You Do That?

Writers are asked many general questions about their craft.

…”What is your overarching philosophy regarding the inherent power of fiction?”…”What IS-character-to you?”…”What is the position of place in your work?”…

These are great and important questions, but I’m really curious about the little things. In the “Hey, Why’d You Do That” series, I ask accomplished writers about some of the very small choices they made during the process of composition.

David James Keaton is a very interesting fellow. The gentleman is very prolific and seems very cool. He loves music and crime fiction…but I’m not sure he’s such a big fan of authority figures. His aversion to them is fine by me, as it resulted in the stories presented in Fish Bites Cop! Stories to Bash Authories, a book you should certainly get into your hands and heart. Here is the entertaining manner in which Mr. Keaton explains how you can order the collection:

If you’re looking to buy it (did I already post these retailers somewhere? oh, well), here’s a link to the Comet Press website, as well as links to Barnes & Noble (for locals), Carmichael’s Bookstore (for locals), Powell’s, Indiebound, and Amazon. I listed those in order of preference. Buy it from the publisher or the real stores first, unless you need it on Kindle. Who knows where that Amazon money goes.

Ordering Mr. Keaton’s first novel is a little easier; Broken River Books has made signed hardcover copies of The Last Projector available through their web site. The book will be worth a look; one of the things I wondered while reading Fish Bites Cop! was what Mr. Keaton would do when he had a vast canvas at his disposal instead of many small ones.

Sure, you might want to know about how Mr. Keaton articulates his overall philosophy regarding fiction. You may want to read a 10,000-word essay in which he writes in great detail what makes a story interesting to him. Well, look elsewhere for those things. I’m really curious about some of the small choices that shaped the stories of Fish Bites Cop!

1) Okay, so I made a chart of Fish Bites Cop!’s table of contents as a public service. (You can never find a simple table of contents for story collections!) I also did it so I could look at stuff a little analytically.

| Title |

POV |

Number of Pages |

| Trophies |

3rd |

2 |

| Bad Hand Acting |

3rd |

8 |

| Killing Coaches |

1st |

8 |

| Schrödinger’s Rat |

1st (we) |

13 |

| Life Expectancy In A Trunk (Depends on Traffic) |

1st |

8 |

| Greenhorns |

3rd |

12 |

| Shock Collar |

3rd |

4 |

| Third Bridesmaid From The Right (or Don’t Feed The Shadow Animals) |

1st |

11 |

| Burning Down DJs |

1st |

6 |

| Shades |

3rd |

6 |

| Three Ways Without Water (or The Day Roadkill, Drunk Driving, And The Electric Chair Were Invented) |

3rd |

11 |

| Heck |

3rd |

4 |

| Do The Münster Mash |

3rd |

4 |

| Either Way It Ends With A Shovel |

3rd |

14 |

| Castrating Firemen |

1st (directed at silent interlocutor) |

5 |

| Friction Ridge (or Beguiling The Bard In Three Acts) |

Play |

14 |

| Doppelgänger Radar |

3rd |

4 |

| Queen Excluder |

3rd |

12 |

| Don’t Waste It Whistling (or Could Shoulda Woulda) |

1st (directed at silent interlocutor) |

3 |

| Three Minutes |

3rd |

3 |

| Bait Car Bruise |

1st |

3 |

| Clam Digger |

1st |

8 |

| Swatter |

1st |

8 |

| Three Abortions And A Miscarriage (A Fun “What If?”) |

3rd |

14 |

| Catching Bubble |

3rd |

3 |

| Doing Everything But Actually Doing It |

3rd |

9 |

| The Living Shit (or Mosquito Bites) |

1st |

6 |

| Warning Signs |

3rd |

3 |

| The Ball Pit (or Children Under 5 Eat Free!) |

3rd |

6 |

| Nine Cops Killed For A Goldfish Cracker |

3rd |

22 |

There are 30 stories in the book.

The longest story is 22 pages.

9 of 30 are longer than ten pages.

10 of 30 are between six and ten pages.

11 are under five pages.

How come the stories are so short? Are you influenced by the Internet-inspired growth of the popularity of short-shorts? The stories are very “idea-oriented”…are you consciously trying to get the idea out of there as quickly as possible? Your prose is fun and punchy; do you feel you need to accentuate that part of your writer’s toolbox?

DJK: Interesting! These statistics are new to me. Did you like the scary fish picture on the contents page? I like that fish. That’s what I imagine goldfish crackers look like in our bellies. Well, as far as length, a couple venues that I was submitting to did dictate length. For example, “Warning Signs” went to Shotgun Honey, which had a 700-word limit, an odd but challenging (and kinda arbitrary) number. Also, many of these shorter pieces were written when I had zero publications to my name and I thought I could somehow crack that elusive code by writing tiny flash pieces and “get my name out there.” Translation: Give fiction away for free! Instead, this mostly meant getting Word Riot rejections five or six times a day (fastest rejections ever!). And this might be kind of a boring answer, but most of the stories are as long as they wanted to be. Well, a more boring answer would actually be “as long as they need to be.” But, truthfully, some of them probably needed to be shorter. But it’s not about what they need. It’s what we need, right?

2) A lot of us have real trouble figuring out character names. Many of your protagonists are named “Jack” or “Rick.” Why do you do that for? Are you making a point about how everyone is kinda the same, regardless of names? Or do you just like that the names are short and easy to type?

DJK: You mentioned to me in an earlier conversation how Woody Allen claimed he used names like “Jack” because they are so much more efficient, and I’m totally on board with this reasoning. It’s like Jeff Goldblum in The Fly and his closet is full of the same shirts and pants and jackets – because this means he doesn’t have to expend any brainpower on unimportant things. Although, to be fair, Goldblum’s character does all his best thinking once his girlfriend buys him his first very ‘80s bomber jacket. But for me, naming a character “Jack” is also like a shortcut to not having to name someone at all. “Jack” feels like a not-name to me, not as obviously anonymous as “John,” and it sort of sounds like a verb, too, so that’s a bonus. I’m just not that interested in names. I also don’t enjoy describing characters. Not sure where the aversion comes from, but I’d number little stick figures if I could!

Also, whenever there’s a “Jack” who is a paramedic, that’s actually a tiny snippet of my upcoming novel The Last Projector. In that book, there’s just the one Jack. Well, he’s kind of a couple people, too, but that’s another story. But in Fish Bites Cop!, the Jacks are different people, unless they’re paramedics. If that makes any sense. This answer has gotten so long and thought-consuming that I’ve now reconsidered and may start using normal names again.

3) “Nine Cops Killed For A Goldfish Cracker” is a really cool story. And you do a cool thing in it. There are three big countdowns that control the progression of the story.

- Jack starts killing law enforcement officers…the title lets us know he’s going to reach nine by the end of the story.

- One of the goldfish in Jack’s bowl ate a thousand dollar bill. The fish are executed one by one in search of the prize.

- The narrator compares Jack’s journey to that of a football player making his way down the field to the end zone.

How did you make use of these countdowns in your story? How did you make sure that the “mileposts” passed quickly, but not too quickly? How did you make the countdowns seem organic instead of all contrived and stuff?

DJK: Thanks! The countdown that shaped the story the most was the deaths of the titular “nine” cops (ten, actually). By thinking of creative ways to murder them, it gave me a very convenient way to map it all out. The countdown of the dying fish was a heavy-handed parallel to the dying cops, so that countdown was supposed to be like a Star Trek mirror-universe version of what the drying fish and dying cops were going through. The yard-line countdown was added in the 11th-hour of writing, to smooth it out and to accelerate things a bit more. Once I added yard lines, the rest of the football imagery started popping up organically and things really got fun. But the deaths of the police officers were definitely the story’s engine, and not just because I knew that a reader would expect exactly nine police officer deaths as promised, and I knew I had to deliver. But it drove the story because, when I wrote it, I’d been working late hours at my former closed-captioning job, and we had short, unhealthy lunches built into our demanding captioning duties, so that countdown was also a way to get a little bit of the story done each night on my 15-minute lunch break. One little murder a day, I’d tell myself, and I’d be home free in a week! How many times have we said that to ourselves?

4) Several of the stories have alternate titles. (For example, “The Living Shit (or Mosquito Bites)”). Coming up with titles is hard for a lot of us. Why did you include some alternate titles?

Some of the titles are really descriptive and reflect what happens in the story (“Killing Coaches”) and some are a little more “fun.” What do you think is the relationship between the title and the story?

DJK: Most of the alternate titles in the collection are their original titles. “The Living Shit,” for example, was renamed “Mosquito Bites” to make it more palatable and get it published. But I always preferred the uglier title, so I switched it back. In fact, the original title of “Nine Cops Killed for a Goldfish Cracker” was “Fish Bites Cop.” But instead of adding an alternate to that already very long title, I just called the collection Fish Bites Cop instead. Problem solved! That meant the newspaper headline at the end of the story is also swapped around. Now the newspaper reads, “Fish Bites Cop!” too. Which I kind of prefer, actually. And hijacking that story title to make it the title of the book suited the collection in many unexpected ways.

But, yeah, some of the “fun” titles were titles I had kicking around that I really wanted to write a story around. Like “Either Way It Ends With A Shovel” was actually an email subject line that my friend Amanda and I passed back and forth at that captioning job whenever we were disgruntled. So that title was her idea actually. To write a story around it, I just had to think of the two “ways” that would go with it. And the question of burying someone or digging them up seemed to be the only option.

5) “Greenhorns” and “Clam Digger” are two of my favorite stories in the book. They’re also a little different from the other stories, as they feature fantasy/supernatural elements.

How come there are only a few horror-y stories in the book? The rest seem extremely hard-boiled and realistic. (Even though the stories feature “extreme” events, of course.)

DJK: When I wrote most of these stories, I was in grad school at the University of Pittsburgh, and many were sort of an affectionate raspberry to the typical MFA-style “lit” story. So I was purposefully playing with every genre I could. The fact that the vast majority also incorporated authority bashing of some kind is a mystery for a psychologist to unravel. Hopefully, a psychologist who is just starting out so that he or she is real hungry and really, really wants to get to the bottom of these things. Or maybe a recently martyred movie psychologist who will absolve me with four magic words, “It’s not your fault.”

6) You’re real good at using unexpected verbs.

In “Bad Hand Acting,” the janitor doesn’t “walk around” the mob of police. He “orbits” them.

In “Either Way It Ends With A Shovel,” the character doesn’t just “look at” or “see” a bunch of bodies in his car trunk. He “studies” the bodies and “counts” the “elbows and knees as tangled as his guts.”

In “Shades,” the narrator “drops” a dollar in a peddler’s hand, which is a lot less secure than “handing” a bill to a person.

How do you know when to use a regular old boring verb and when to use a cool, unexpected one?

DJK: Back in school, I was told verbs are very important to bringing a scene to life and their power shouldn’t be squandered through use of lazy words like, “are” and “to be,” like I just did in this sentence.

7) One of the things I really like about the stories is that you include a lot of fun “extra” stuff in your work. “Clam Diggers” is very much a story about a man relating how his brother disappeared. Still, you manage to sprinkle in a cool image/story about how the father taught the sons to turn bathroom graffiti swastikas into “neutered” sets of boxes. Unfortunately, writers like me have led sheltered, boring lives, depriving us of the opportunity to come across these kinds of interesting anecdotes and ideas. How many of these cool things in the stories come from your real life? Should sheltered writers like me just allow myself to make up stuff? I’ve obviously never planned an inside job scam on a casino…should I just stop restricting myself and assuming I couldn’t write such a story?

DJK: Neutering swastikas into tiny four-paned windows is a favorite pastime of mine, as I found that moving to Kentucky means more than the usual quota of bathroom-stall neo-Nazi graffiti. See this is where the revolution will begin… on the toilet! And many of the digressions, er, details do come from my day-to-day or past adventures. I did win and lose and win back about three grand at roulette, and I committed all those ridiculous infractions at the roulette wheel at the MGM Grand Casino in Las Vegas. I’d like to say that was research, but it was my friend’s crazy wedding. I didn’t try to scam them, of course. All the flavor that my personal experience can bring to the stories stops just short of the actual crimes. Except for one. Maybe. Sort of. Next question!

8) You REALLY like to start stories with the inciting incident or with a sentence that represents the overarching feeling of the piece or its narrative thrust. See?

Shades: “She was sure one of them was watching her.”

Burning Down DJs: “Before the night ends with me crashing through the woods in a stolen police car, I’ll drive around stuck on one thought.”

Queen Excluder: “There were sitting down to dinner when the phone rang.”

Castrating Firemen: “I will leave work to get you a cigarette because you’re crying.”

Either Way It Ends With A Shovel: (in italics) “Are you going to bury someone? Or dig someone up?”

How much of this is planning and how much comes in the second draft? Are you only doing it because most of these are crime-related stories and plot is really important?

DJK: Those examples were part of the original drafts. I’ve always been a fan of getting things going in the first sentence, to engage both the reader and the writer. And because I can’t wait to get the main idea out, front and center (like the “Are you going to bury someone or dig them up?” question in “Either Way It Ends With A Shovel”) and because I trust myself a little more with the plot rather than the prose. At least until the story gets cooking.

9) So I think I understand why you have thirty stories about authority figures (police officers, firemen, paramedics). It’s probably the same reason I have 150 stories about ugly dudes whose flawed natures has resulted in the fact that none of them have ever had a healthy relationship with a woman. These are topics of particular and personal interest to us, so we’re going to write about them.

What I wanna know is how you figured out the order for all of the stories. (We’re all hoping to have the same assignment someday!) How come the super-long award-winning story was last instead of first? How come the shortest story was first? What kind of experience were you trying to shape for the reader?

DJK: When it turned out I’d accumulated thirty stories that punished police officers, firemen, paramedics, high school coaches, etc., I was kind of surprised. It really wasn’t a conscious effort. Well, there were probably about twenty stories stockpiled with this similar theme before I realized the connection, and then I wrote ten more because I felt like I was on a roll and wanted to get it all out.

It’s still not all out though. A beta reader is going through my novel, The Last Projector, right now, and for kicks he counted up the total uses of the word “cop,” “officer,” and “police.” You might enjoy this with your statistics fetish earlier!

In 500 pages, there are around 700 uses of these terms. Second most used is the word “fuck” with 600. And most of those “fucks” and “cops” are probably pretty closely intertwined. And this is not a novel about police officers. So I guess it’s out of my hands.

As far as the order of the stories, that was sort of complicated:

“Nine Cops Killed…” wraps up the book because it’s the title story, and I feel like it’s a big party, a fun bash where the reader can be rewarded for making it through the whole thing. And the shortest story starts things because “Trophies” felt like a mission statement to me. It had a lot of the elements that are consistent throughout, regardless of the genre hopping.

But as far as the order of the stories, I spend a loooooooong time on that. I definitely “mix-taped” it High Fidelity style. The first “song” starts off fast, then the next song kicks it up a notch. Then the next song slows things down a notch, etc. etc. And I also wanted stories that were first-person to avoid following each other, lest people think those “Jacks” were the same Jack, of course. And I wanted the genres to be spread out, so that people didn’t expect a third monster movie after a monster double feature. And after all that work of mix-taping, I read an article on HTML Giant that declared very definitively that, “Short Story Collections Are Not A Mix Tape!” and then I was satisfied that I had done the right thing.

10) Look at the last few pages of “Clam Digger.” This cool story is told by a first-person narrator who is relating events that happened a long time ago. He therefore has access to a lot more information than the younger version of himself.

So the narrator lets us know this is THE STORY OF HOW HIS BROTHER DISAPPEARED AND YOU CAN BELIEVE HIM OR NOT; HE KNOWS WHAT HE SAW. (We’re also informed he’s participating in some kind of interview.)

So the bulk of the story finds the narrator telling the story in the past tense, chronologically jumping from one significant event to the next.

But check out the end of the story. We’re getting the “money shot,” so to speak. The mystery of the brother’s disappearance is being revealed…

Then you cut to a new section, leaping from the past to the present to the past again. Why did you break the pattern established by the rest of the sections? What was the effect you were trying to create? Are you willing to apologize for my newfound fear of clams and other mollusks?

DJK: I guess that was an attempt to build suspense, sort of use those Sam Peckinpah directorial editing tips where you cut away right when the shot has peaked. I also maybe stutter-stepped there at the end because I wasn’t sure how I was going to wrap it up. The natural ending of that story felt like it should be in the past, since that’s where the mystery was, but there had to be resolution in the present, too. So I tried to do both, at the risk of the dog in Aesop’s fable who growls at his reflection in the water and loses both bones.

“Clam Digger” was also my first run at a “Lovecraftian” story. So I had some tortured soul spinning some yarn about the horribleness he’d witnessed, some large ocean-dwelling critter that may have driven him insane. But other genres started to cross-fertilize while I was writing it, and the story that resulted is really more psychological horror than anything.

I do apologize for your new clam and mollusk aversion, though. But it’s better than an aversion to naming characters, so you should be thankful! And it’s only fair this happened to you because those things freak me out, too. I mean, look at clams for a second, if you have one handy. You think it’s sticking its tongue out at you, but it’s a foot? You think it’s sticking its eyes out at you, but that’s its nose? That’s insanity on the half shell right there.

David James Keaton’s award-winning fiction has appeared in over 50 publications. His first collection, Fish Bites Cop: Stories to Bash Authorities, was named This Is Horror’s Short Story Collection of the Year and was a finalist for Killer Nashville’s Silver Falchion Award. His debut novel, The Last Projector, is due out this Halloween through Broken River Books.

Short Story Collection

2014, Comet Press, David James Keaton, FISH BITES COP!, Why'd You Do That?

Writers are asked many general questions about their craft.

…”What is your overarching philosophy regarding the inherent power of fiction?”…”What IS-character-to you?”…”What is the position of place in your work?”…

These are great and important questions, but I’m really curious about the little things. In the “Hey, Why’d You Do That” series, I ask accomplished writers about some of the very small choices they made during the process of composition.

Jim Ruland is a very interesting man. Not only does he write about music and books, but he’s one of those people who manage to do a little bit of everything and to do them all well. Of greatest note to me is his fun aesthetic, both in the work he produces and the forms in which he produces. If you take a look at his web site and his Tumblr page, you’ll see that he loves to experiment with visuals and narrative form, while still fulfilling his fundamental duty to tell a story and to entertain.

Sure, you might want to know about how Mr. Ruland articulates his overall philosophy regarding fiction. You may want to read a 10,000-word essay in which he writes in great detail what makes a story interesting to him. Well, look elsewhere for those things. (The gentleman has appeared on at least one podcast.) I’m really curious about some of the small choices Mr. Ruland made while writing Forest of Fortune.

1) So the book is split up into four sections: Winter (79 pages), Spring (97 pages), Summer (53 pages), Fire (58 pages). I think I get why the last section isn’t named for a season. Here’s what I want to know: How come the second section is the longest? Why are the last sections shorter than the first two when there are so many conflicts to resolve?

JR: That’s weird! I didn’t notice that. I would have guessed the shape was more like a funnel: wide at the top and narrow at the bottom. I’m not sure what shape this is. Some kind of exotic bong? Forest of Fortune tells the story of Alice, Pemberton and Lupita and we get to know these characters through their own point of view. What I found is that with three principal characters there’s a lot of scenes to be set, personal histories to populate, worlds to be built, etc. But as the story approaches its climax, the storylines converge. Plus, I wanted the end to be the best part of the book (like The Hangover) (kidding/not kidding) so that it’s a rewarding experience for those who stick with the book to the last very page.

2) At the beginning of the book, Pemberton is running away and drowning in drink. Lupita has a bit of a gambling problem and is adrift in her life. Alice has a neurological setback influenced by her personal problems. How’d you deal with having three parallel protagonists who aren’t exactly as active and dynamic as James Bond or as shallow as a character on a TV sitcom?

JR: I don’t remember where I got it, but at some point I picked up the advice that one should construct characters as if they were going to be played by brilliant actors and actresses. In other words, there are no bullshit characters with throwaway lines. Give every character great scenes and memorable dialogue. In early versions, it was clearly Alice’s book (at least in my mind, anyway). Then for a while it was Pemberton’s. But I discovered that it didn’t really matter which character I intended to make “the main character” as each reader chooses his or her own.

3) Each section of the book is divided into brief chapters. I’m guessing that one reason you did this was to help the reader negotiate the transition between focal characters. But sometimes you have two sections in a row that focus upon the same focal character. Why’d you do that?

JR: Yes, I kept the chapters short because I didn’t want the reader to “forget” about a character. Sometimes I had to double up on a particular character for fairly mundane reasons: they keep different hours. Pemberton works at the casino during the day while Alice works the graveyard shift and Lupe comes and goes as she pleases.

4) Pemberton’s unpleasant boss, O’Nan, uses a beautiful gold Montblanc fountain pen filled with a cartridge of red ink. Why’d you choose to put that pen in his hand?

JR: One of the things I learned as a teaching assistant was to avoid using red pens when marking up student work. This advice even came with the slogan: “Don’t bleed on the page.” O’Nan is the kind of guy who not only enjoys bleeding on the page, he desires to do so with style, hence the Montblanc. I didn’t realize until very recently that fountain pens were objects of intense interest to their collectors. If I had known, I might have chosen a pen “worthy” of O’Nan’s low character.

5) Each section of the book begins with an italicized fraction of a first-person narrative unspooled by, shall we say, an important character. What do you want writers to think the first time they read the italicized section before going into dozens of pages of third-person prose?

JR: I don’t want to say too much about these sections because they are very important to the framing of the story and impact the way the reader perceives it. Suffice to say I want readers to be aware that there is a historical context that may or may not antagonize preconceived notions about the inhabitants of early California. Hopefully, the reader’s understanding evolves as he or she move through the novel’s four seasons. I had neither an agent nor a publisher when I finished Forest of Fortune and I worried that these sections would come under fire at some point, but I’m happy to say that never happened.

6) So the reader doesn’t have to be Sylvia Browne to guess that the lives of the three focal characters will intersect and that intersection will be centered around the Forest of Fortune in some way. But check it out: Pemberton’s story literally ends in close proximity to the Forest of Fortune. Alice’s story literally ends in close proximity to the Forest of Fortune. Lupita’s story ends figuratively in close proximity to the Forest of Fortune. How come?

JR: Forest of Fortune is both a place within the casino and a fantasy. When I worked at an Indian casino, the names of the various establishments were a source of great amusement. For instance, we actually had a Dreamcatcher Lounge, as hokey as that sounds. My employment coincided with the recession, so I felt bound to the place. I wanted to leave, but felt like I couldn’t afford to quit. This feeling intensified when I went into recovery for alcoholism. I wanted to find a healthier place to build a new life for myself, but I was stuck at the casino. I felt trapped there. It was a feeling that was shared by many of my coworkers and this feeling is a big part of the book. Of course, it was only a feeling. I could have left anytime, but I didn’t. I stayed way too long.

7) The word “lonely” appears a number of times in the book. The three protagonists all seem pretty separated from themselves and from those around them. What are you trying to tell us about your characters? But each of these somewhat passive characters has a confidante. Were you consciously trying to put a mirror up to each of them so you could release characterization and exposition? Were you thinking something else?

JR: To be caught in the grip of an unhealthy experience – whether it’s drug abuse, medical issues, the inability to move on from a relationship, etc. – is extremely isolating. Indian casinos are almost always located in out-of-the-way places, so these places are geographically remote as well. These factors contribute to a species of loneliness that just feels lonelier than other kinds of isolation. It’s not that the characters are passive: they’ve succumbed to forces greater than they are, i.e. addiction, epilepsy, etc. The confidantes are necessary to shake the protagonists out of their way of seeing the world and coerce them into action. In other words, make things happen. Also, and we haven’t touched on this, but the book isn’t all darkness and squalor. There’s a good bit of humor, and that’s a lot easier to pull off when you have two or more characters who are with intimate with one another’s shortcomings.

[Editor’s Note: Aw, I certainly didn’t intend to imply, dear reader, that Forest of Fortune is all “darkness and squalor.” There are many laughs in the book and some scenes that are indeed quite light-hearted. I love Pemberton’s encounter with a conceited former colleague and his scenes with a friend who is also his dealer. There’s a lot of dark humor in Alice’s plight, both in terms of her health problems and her living situation.]

8) Okay, so the principle of Chekhov’s Gun mandated that one of the characters wins the Forest of Fortune jackpot. That’s a given. Here’s the thing: the actual winning of the jackpot occupies about a third of a page. And you seem to zoom through the jackpot to get to what happens after. Why’d your third person narrator go the speed that it did?

JR: One thing that recovery has taught me is that the key to a healthy, happy life is to live in the moment. Don’t dwell on the past or obsess over the future. Be where you are. Casinos antagonize this idea. They are all about suspending the present for the promise of a more rewarding future. Vegas takes this a step further: You can be someone else. Go ahead. We won’t tell. What happens here stays here. When you’re trying to separate someone from their money, you don’t want them to dwell on the consequences of their actions.

9) There are some REALLY pretty and powerful images in the book:

“As Lupita labored up the grade, she wondered why some mountains out here on the outskirts of the desert were jacketed in soil while others resembled piles of boulders stacked by a gigantic hand. Not for the first time she wondered how two mountains could be the same height and shape, but so different. One covered in verdant scrub, the other rocky and barren. They sat side-by-side, inviting comparison. Similar but different, like Lupita and Mariana.”

“Maybe O’Nan was taunting him because being here was like pressing up against the window of his former life: Pemberton could look all he wanted but he couldn’t quit grasp what he once had.”

“…a hawk alighted on the picnic table in her backyard, a jackrabbit twitching in its talons. Lupita watched in horror as the hawk tore the thing to pieces. To be in love is to be tormented: you’re either the rabbit or the hawk.”

I have my own book that I’m trying to make good, so I gotta know: How’d you come up with such potent images that are so closely connected to character?

JR: Thank you. For this project, I really focused on the characters. I love story stories. A desire to know what’s going to happen next is what drives me as a reader or filmgoer or TV watcher. Once I’ve got the story down, I can think about other things that are going on, the creative choices being made. My first attempts at novels were marred by a fixation on scenarios in which characters were neatly slotted into their roles. For Forest of Fortune I spent a lot of time thinking about how the individual characters see the world. I think it helped that all of the characters spend most of their time in the same place. Of course, they’re going to see it differently!

10) I love the cover art for Forest of Fortune. Slot machine? Check. Your name and the book’s title in casino-ey neon? Check. The image of the slot machine is askew and slightly scrambled? Makes sense. Three visible reels instead of the five described in the book? Stop being stupid, Great Writers Steal guy. If there were five reels in the image, each would be too tiny. Who are you to criticize? What have you ever done? Okay, geez, me. Hit myself in the Vital Lie, why don’t you?

Here’s my question: Like I said, I love the cover art. I am interested in the way the art and book are related. I read Forest of Fortune as a fairly straight “literary” novel, whatever that means. The cover art seems like it wouldn’t be out of place on a book with even more supernatural/mystery elements. (The book seems especially mystery-y around page 118, when your narrator seems to suggest that the Forest of Fortune may be cursed.) If you had a magic bookstore wand and could put the novel in any department you like, real or imagined, what would it be?

JR: Thanks, I’m a big fan of the cover, too. The designer, Sylvia McArdle, did an excellent job. It’s a concept I presented to my publisher and I couldn’t be happier with the result, but if you like the cover then you’ll really like this:

I’ve always been drawn to genre fiction, weird stories, work that hybridizes established modes of writing. On one hand, Forest of Fortune is a work of fiction that cozies up to the supernatural, collides with crime and is shrouded in a bona fide mystery. One the other hand, it’s a deeply personal novel that draws on my experience of hitting bottom while working at an Indian casino. I like to call it my autobiographical ghost story. I worried about this up until last summer when I read Roberto Bolaño’s 2666 and saw that it was possible to make high art out of low culture. I’m not comparing myself to Bolaño, but it eased my anxiety over whether or not there is a name for what I’m doing.

As for where I’d like Forest of Fortune to be shelved, that’s easy: I’d want it to hang out with the bestsellers.

Jim Ruland is a Navy veteran, former Indian casino employee, and author of the short story collection Big Lonesome. He is the host of Vermin on the Mount, an irreverent reading series based in Southern California. He is a columnist for the indie music zine Razorcake and writes The Floating Library, a books column, for San Diego CityBeat. His work has been published in The Believer, Esquire, Hobart, Granta, Los Angeles Times, McSweeney’s, Oxford American and elsewhere. Ruland’s awards include a fellowship from the NEA and he was the winner of the 2012 Reader’s Digest Life Story Contest. In April 2014, Lyons Press will publish Giving the Finger, co-written with Scott Campbell, Jr. of Discovery Channel’s Deadliest Catch. He lives in San Diego with his wife, visual artist Nuvia Crisol Guerra.

Novel

Forest of Fortune, Jim Ruland, Tyrus Books, Why'd You Do That?

Writers are asked many general questions about their craft.

…”What is your overarching philosophy regarding the inherent power of fiction?”…”What IS-character-to you?”…”What is the position of place in your work?”…

These are great and important questions, but I’m really curious about the little things. In the “Hey, Why’d You Do That” series, I ask accomplished writers about some of the very small choices they made during the process of composition.

Aaron Burch may best be known as the editor of Hobart: another literary journal, but we mustn’t forget that he’s a great writer in his own right. Backswing, released by Queen’s Ferry Press, is Mr. Burch’s first short story collection. If you haven’t already done so, why not order a copy of his book from the publisher?

Sure, you might want to know about how Mr. Burch articulates his overall philosophy regarding fiction. You may want to read a 10,000-word essay in which he writes in great detail what makes a story interesting to him. Well, look elsewhere for those things. I’m really curious about some of the small choices Mr. Burch made while writing and putting Backswing together.

1) Here are some of the sentences from Backswing:

“She calls Roy, says: I have a new trick.”

“We built a fence around the remains, left it as it was in case he should return.”

“We elected Mo as recorder, made him repeat back to us, sometimes, the moments that seemed most important or confusing…”

You seem to like this sentence structure where you start with the subject of the sentence, pop in a comma and then omit the conjunction before the next verb. What’s up with that? What is the effect you’re trying to create?

AB: I do, I like that sentence structure a lot. I like the way it looks on the page, the way it sounds, the way it almost feels a little off, grabs or startles your attention a bit. I’m trying to think of where it came from, and I’ve got a few ideas. One is that it grew out of writing short-shorts: trying to make every word count; trying to cut words to, say, get down under Quick Fiction‘s 500 word limit; and also probably from Coop Renner at elimae‘s having edited pieces and showing me how I could play with language and sentence structure. The other thing that jumps to mind, and this is kinda a perfect first question/answer for “great writers steal,” is how influential Sam Lipsyte is. Venus Drive is one of those collections I go back to, over and over, probably as frequently as the nearly universally heralded Jesus’ Son. Maybe my favorite sentence (or, I guess two sentences) of all time are from “Old Soul”:

Somebody told me they were exploited. Me, I always paid in full.

I don’t know, I think the way that second sentence turns is perfect. Rereading, it’s doing something a little different than the examples you point out above, but there’s something about the comma as hingepoint for a sentence that I feel is really interesting, and I’ve probably been emulating that Lipsyte move for years. Though now, of course, I never think about it when writing, I think I just like the sound of it.

2) My story of mine that I kinda like the best has the narrator performing magic tricks. It’s really really hard to write magic tricks in fiction because the writer must conceal things the narrator knows from the audience in the story and the reader. But we can’t hide too many things or our reader won’t understand what’s happening. Your story “Prestidigitation” features a magic trick interspersed with exposition.

How’d you keep the magic clear to the reader? What were you thinking when you tried to describe something inherently visual in words?

AB: Again (and I’ll try not to add this disclaimer to every answer, we can just assume it applies across the board?), a lot of what makes it work (or, I hope it works, at least) is me playing with the story while writing it but not thinking this explicitly about what is and isn’t working, but just progressing by what feels right. Looking back now though, I think the tense and POV is pretty important here. It’s in 3rd person, but much “closer” to Roy, and is present tense, so we’re seeing Linda’s magic trick at the same time as Roy is — they’re a couple and so he knows some of the behind-the-scenes of her magic, but this is a new trick so he doesn’t know what she is going to do until she does it, so that’s where we are, too. He’s not sure what is going to happen next, but he’s curious, and he’s not just wondering what will come next but is at the same time trying to figure out how she’s doing what she’s doing. That feels like a good place for us, the readers, to be in, yeah?

That said, I did think about describing everything enough so that we could see it as much as possible. Going back, making sure where each of her hands are, what they’re doing, all of that, is as descriptive as possible so that we could follow along.

3) “Church Van” is a real cool story. There are two Roman-numeraled sections in the piece. The first one is a third person POV limited to Densmore, the protagonist. The second one is a first person POV whose narrator focuses on the reaction of the group trying to understand what Densmore was up to.

We’ve all been told a jillion times not to switch POV, but breaking that rule works in “Church Van.” Why does it work? Is it just the numbered sections? How come you didn’t just use a third person omniscient POV in the whole story?

I really think of the story as in two parts. (Though I can’t remember at what point during writing it this happened, if that was kind of always there or if it grew into that. Probably the latter, actually.) I think the story started with that first half, the idea of this dude eating a car. To again play into the idea of “great writers steal” (and also maybe over-admitting influences?), that germ of the story was more or less stolen from Harry Crews’s short novel, Car. Only, I’d heard of the book but hadn’t yet read it, and so kind of wanted to try to write a “response” to something I hadn’t actually read, see how much/effectively I could turn it into my own thing. Then, like a number of the stories in the book that are playing with more Biblical ideas, it turned into me wanting to play with the mythology of it all. I liked the idea of trying to set something up that was both the “origin story” and then the myth that it got turned into. I think the way that works, in this story, is the juxtaposition of those two sections and POVs. I actually remember workshopping this story and some comments that it might (would?) work better if the two halves were threaded together, which I guess feels more traditional, but I really like the jarringness of it this way, of how one works with and against and in response to the other.

4) “Fire in the Sky” rocks. It’s about a group of friends sharing a last night of stupid fun before one of them gets married. Something real bad happens to the groom-to-be in the story’s explosive climax. The narrator and Jeff head out on their own while things get sorted out.

I kept thinking that you were gonna have Jeff and the narrator come back to the groom-to-be. Why’d you end the story away from Hank?

AB: Again, and maybe even more than any of these other questions: intuitively. It’s actually maybe a bit more of a “short-story-y” ending in my mind than I typically like, ending with them just running, but it felt right. I don’t think I ever even considered having them return. I guess, if this were a chapter or piece of something larger, they’d have to and the story would then deal with the ramifications of what had happened, but as-is, they are just purely in the moment, which feels a nice way to end things.

5) People like me don’t have a short story collection, but we really want to publish one one day. The stories in Backswing have a mixture of POVs. It seems like an even split, give or take, between first and third with a second person story thrown in there.

Did you have this kind of variety on your mind when you put all of the stories together and put them in order? The book starts with a story about a guy who is forced to deal with his problems and ends with a story who seems to be heading out on a new adventure, leaving an old life behind. Did you do do this on purpose?

AB: Yeah, this was probably the aspect of the book I did think the most about. I really wanted it to feel like a book, not “just a collection” (as Kyle Minor says in his new Praying Drunk, albeit in a completely different way), but I also really wanted it to have a good variety. Which is maybe wanting to have it both ways, but I felt like it was possible.

When I was writing the stories individually, I want to say something super “writer-y” like I just wanted to find the POV and tense that best fit the story being told, but the reality is probably more that I was often giving myself these small challenges to try to keep from repeating myself. So…how would this story work in first person plural, etc.? And then there’d probably be a push and pull between one being adapted for and influencing the other, and vice versa, such that each hopefully did push toward using those kinds of aspects of itself toward its best benefit.

So, that’s why I had a variety of stories and, like I said, I wanted to try to find the best of way putting them together and presenting them. Which meant trying to find the “best” order for the book, and also cutting stories that maybe felt too similar and didn’t bring anything especially new to the whole, even if they were strong on their own, and that kind of thing. And also having friends read it and give input.

6) During my MFA, my awesome teachers (Lee K. Abbott in particular) advised me to use pop culture references in a smarter manner. They’re real smart and I have indeed cooled it a great deal. Sometimes, however, we just hafta use pop culture references. You start “Flesh & Blood” with a reference to Bret Michaels’ eyes and invoke “Unskinny Bop.” You mention Wall Street and Glengarry Glen Ross in the book. You mention Corvair Racers.

How do you decide when a pop culture reference should stay? What do you hope a reader who was born in 1997 thinks about the references?

AB: I probably overuse pop culture references, so I maybe could have used a teacher that told me that, actually. I find myself, in conversation but also just to myself when thinking of things, making a lot of comparisons to movies, especially, and so I find myself doing that in my stories, too. I think, too often, they’re probably used either as short cuts or just because they’re fun, so I guess the trick is to try to make them purposeful. I often drop the in to show that they are how my characters are connecting to the world, not just me, the author. As far as connecting to different generations… I guess you hope that the writing around the references is good and clear enough such that if someone hasn’t seen the “Unskinny Bop” music video, they still get what you mean and they’re not at a loss, and if someone has, it’s a bonus.

7) I am always thinking about when writers omit question marks. It’s controversial to some, but it’s a valid technique writers can employ to shape the reader’s experience.

Why’d you omit the question marks in stories like “Prestidigitation,” but you did use them in stories like “Unzipped”?

AB: Like saying I would push myself to use different POVs, I think at times it was a challenge (how to make it make sense that this story doesn’t have them, whereas this other one does?); and like me repeatedly calling out the very name of this website, it was at other times probably just because I was reading authors that didn’t use them.

Probably, mostly, it was intuitive. I think that intuition, for myself, meant using them for the more traditional “realism” stories (like “Unzipped,” “Scout,” etc.) and omitting them for the stories that felt a little more… I don’t know what you want to call them. “Experimental” isn’t quite what I mean.

8) Writers are also always thinking about how to use white space. And why to use it. And when. If you look at the middle of “Fire in the Sky” (page 87), you have your characters standing around in tuxedos and watching fireworks light up the sky. Then you have some white space before “Todd dropped a mortar into the tube.”

It doesn’t seem like much time has passed. It seems like the white space is optional and you could just have kept those two paragraphs together. How come you put white space there?

AB: I think there’s a couple things going on here. The first is that I think more time has passed than it maybe seems. They’re standing around in tuxes, watching fireworks at the beginning of the night, and then white space, and then the end of that “Todd dropped the mortar…” sentence is “…same as we’d been doing all night.” So there’s been a night’s worth of this already, during that white space break.

The second is that I try to use section breaks as not just signifiers of time having passed but as…well…just that. A “section break.” Meaning I want each piece in between those white spaces to work as its own section, almost maybe like a short-short, even, if I want to tie it back up to that first answer.

9) “Flesh & Blood” begins with two paragraphs about the teenage protagonist (Ben) noticing his burgeoning sexuality through the lens of what he sees on 1980s-era MTV.

My question is this: why do they still call it MTV when there’s no M on the TV?

Just kidding. After the reader is reminded about the thinly veiled expressions of sexuality in early music videos, you use a section break and write, “All summer, Ben has kept to his new bedroom as much as he can get away with.” That sentence introduces the protagonists, hints that he’s undergone some kind of big personal change and sets up the beginning of the school year-a transition that kicks off the narrative. In other words, it’s a rockin’ first sentence.

How come you began the story with the MTV stuff instead of the next section that really kicks off the events Ben goes through?

AB: AGAIN, like most of this, I hadn’t actually thought about this until now, but I’ve been thinking about it a lot, in how to reply. I can really only say that, for me, introducing MTV always felt like the beginning of the story. (Actually, even more specifically, it was first written with each piece of the narrative interspersed with a detailed description of that “Unskinny Bop” video, with the description of Bobby Dall’s Corvair Racer, etc. Which was super helpful for me, while writing the story, but then ultimately didn’t work. But I still wanted to open on the video.

I also think, you’re right, that second section is maybe a more traditional story opening, and does a lot of what you’re supposed to do to introduce a story. And maybe starting with MTV is not technically the best opening and over-relies on the aforementioned pop culture references, but I think that song and video are also exactly the “transition” you mention that is basically what the narrative is about, Ben’s “noticing his burgeoning sexuality,” all that. That video was 1990 and Poison was all over MTV, but within the year, “Smells Like Teen Spirit” had appeared, making Poison just about the furthest thing from cool.

Also, and maybe most importantly, starting with Bret Michaels just seemed more fun.

10) I’ve noticed that a lot of the stories in Backswing are about men who are dealing with grief in different ways, many of which aren’t necessarily healthy.

As a successful writer with a (soon-to-be) published collection of short stories, what do you think when some random weirdo tells you what he thinks your writing is about?

AB: You know… it seems kinda awesome. I think it’s often hard to know what your own stories are about, or even to see some of your own tendencies or common themes or to try to summarize your own writing. I think “about men who are dealing with grief in different ways, many of which aren’t necessarily healthy” is probably just about a better way of super briefly summarizing the connections of the stories than I could do, plus it’s obvious from the above questions that you actually spent some time with the book, and so that’s kinda exactly what you’re hoping for, I think.

Aaron Burch is the editor of HOBART: another literary journal, and the author of the novella, How to Predict the Weather, and How to Take Yourself Apart, How to Make Yourself Anew, the winner of PANK’s First Chapbook Competition. Recent stories have appeared or are forthcoming in Barrelhouse, New York Tyrant, Unsaid, elimae and others.

Short Story Collection

2014, Aaron Burch, Backswing, Queen's Ferry Press, Why'd You Do That?